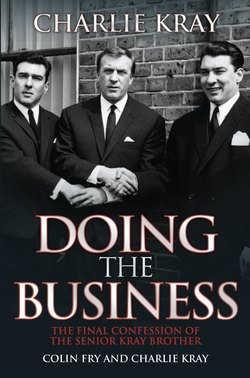

Читать книгу Doing the Business - The Final Confession of the Senior Kray Brother - Charles Kray - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

INTRODUCTION

ОглавлениеCHARLIE KRAY IS DEAD - but he is not forgotten!

On 4 April, just into the start of the new millennium, Charlie Kray succumbed to the effects of a sudden heart-attack and quietly passed away at St Mary’s Hospital, only a stone’s throw away from Parkhurst Prison on the Isle of Wight. He was, at the time, serving a 12-year sentence for his part in a £39 million cocaine smuggling plot. He died broke, homeless — and alone.

The demise of ‘Champagne Charlie’ made the front pages — how Charlie would have loved to have seen the obituaries, the media hype, the gossip and the gas. And he would have been thinking all the time of the money he could have been making, selling his story — loads of money, by the bucketful. He would have laughed all the way to the bank!

But the circumstances surrounding his death were all but cheerful, hopeful, colourful — and there was no humour of any kind. The troubles surrounding Charlie Kray started in 1999 when he suffered his first stroke, causing him to have reduced circulation in his legs and feet. And he never overcame the effects of this, brought on as they undoubtedly were by the trial, the conviction, the appeal process and his imprisonment at Frankland Prison.

To his friends, Charlie had openly admitted his guilt in the cocaine smuggling operation — but he was after the money, and in no way did he intend to go through with the deal. He was put under extreme pressure by the police officers involved to come through with the goods — and being Charlie Kray, he knew exactly where he could lay his hands on £39 million worth of cocaine. That was always the problem — it was his making and it was eventually his downfall. Everyone would confide in Charlie — he knew where the bodies were buried, he knew who was doing what and to whom. He knew but he couldn’t tell. That would be breaking his code and Charlie was an old-time criminal — he believed in respect, in tradition, in honesty among thieves.

Certainly, Charlie felt that his current spell behind bars was a gross injustice — it was a sting operation, set up by the ‘Met’ to catch the last remaining Kray still at large. His feelings of outrage and his unmanageable frustrations were exacerbated by the fact that his first stretch in prison was a horrendous miscarriage of justice — he had served seven years for helping to dispose of the body of Jack ‘The Hat’ McVitie, when all the time he was safely tucked up in bed, with not a care in the world. He didn’t know until the following day any of the events of the preceding evening, when his brother Reg Kray, urged on by twin brother Ron, stabbed McVitie to death. But the police wanted the Krays, all three of them, and there was no hope for Charlie, who was inextricably involved in the Firm’s activities. However, it may be well worth noting that Charlie Kray was never on the Board of any of the Kray companies, he was never in charge in any way, shape or form. But Charlie was always there to support the twins, to offer advice — and to make a little something for himself, if he could, in the process.

His first time in prison had not been kind to him — he remembered and remembered, and he regretted and regretted. But it did no good at all. However, he did promise himself that he would never be sent to prison again, never, not for anyone.

One way of trying to come to terms with his life, before and after prison, was to write, and I was privileged to be involved in the writing of this book. All the remembering, all the regretting — it all served a new purpose, a way of redemption and a means of helping him to find his own way in life without the twins — Ron and Reg Kray.

The second time around, first in Frankland and then in Parkhurst, was hard for Charlie Kray. He wasn’t a youngster any more — he was 70 years of age and a pensioner. He lost much of his hair after the first stroke and with the blood circulation problems he became a pitiful, frail and ghostly image of his former self. When he started complaining of chest pains, prison authorities at Parkhurst were quick to act — they decided to send him to St Mary’s for investigations, medical not criminal. Their suspicions were well founded — Charlie Kray was suffering from a heart-attack.

On the following day, Saturday 18 March, news reached Reg Kray in Wayland Prison, Norfolk. The message said simply, ‘Charlie is dying.’ He immediately contacted the authorities at the prison and arrangements were hurriedly put together for him to visit Charlie on the Isle of Wight, probably for the last time. Reg hadn’t seen Charlie for over five years — not since his twin brother’s funeral.

Reg Kray is no stranger to Parkhurst. He served at least 17 years, mainly in isolation, at this establishment — he knows all the rules, all the regulations. He wasn’t keen on going back there, and the thought of confronting Charlie, possibly on his death bed, was not what he had wanted.

At around 8.00am on the morning of Sunday, 19 March, Reg Kray, together with three trusted warders, left Wayland Prison in a white van, driving carefully and slowly through the giant main doors of the prison. The van had arrived earlier, at around 6.45am, but it had to be inspected and checked, even by a sniffer dog, before Reg could be safely put inside. They were taking no chances with their prize prisoner.

The van was quickly on to the M11, and then the M25 around London, to the west. At around 11.00am the warders were hungry so they pulled into Winchester Prison, a scheduled stop for lunch. The meal was the usual thing, something good for the warders, something not so good for the prisoners, but Reg couldn’t eat much — he kept on thinking of Charlie. He wanted to get there fast — at any cost.

The white van, complete with its occupants, made the ferry at Porstmouth early in the afternoon and by mid-afternoon they had reached St. Mary’s Hospital and the dying Charlie. Reg had endured the entire trip handcuffed to two warders, except for a brief interlude when waiting for the ferry, where he was allowed to smoke a cigarette or two while one wrist was freed. On this first day he was allowed to see Charlie for around 45 minutes, still handcuffed to the two warders, one on each side — plenty of time for a quick chat and a few words of encouragement. Charlie hugged his brother, nothing could dent the Kray spirit, but his legs were already beginning to turn black, and the feeling had gone. Reg was under no illusions — it was all true. At 73 years of age, Charlie hadn’t long to live.

The usual words came from trusted hospital sources — Charlie was ‘comfortable and cheerful’ although he had become ‘extremely unwell’. And Parkhurst Prison let it be known that Reg Kray, once gangland crime boss and now a pensioner of some 66 years, was a welcome visitor — he could stay and use Charlie’s cell until his brother was well enough to resume his sentence, or until …

Reg couldn’t even manage a smile for the cameras as he left the hospital. He was smart enough though, shirtsleeved, white casual jacket carefully placed over his arm, not getting in the way of the handcuffs, and the customary blue jeans. Sources at the prison told reporters that the reunion had been emotional — ‘Both men are old,’ they said, ‘and they know they haven’t got long left.’ Reg settled into Charlie’s old cell, and waited. It had been a long day!

The following week passed slowly and painfully, apparently with no end in sight. Charlie was fighting the toughest fight of his life. After all those fights, after surviving all those years, after already witnessing the death of his mother, his father, his brother Ron — was it now to be Charlie’s turn? He didn’t give up easy — he fought every inch of the way. But there was no quick fix, no easy option, no way out.

The speculation grew as Reg Kray waited for his brother to die. Was he just taking a break from Wayland Prison, spending a few quiet weeks on the Isle of Wight, just for the sheer fun of it? Was he manipulating the situation just to get a few more columns in the press, using brother Ron’s favoured media tactic? Well, let me assure everyone — there was no way in hell that Reg Kray wanted to be in Parkhurst, it brought back so many memories, and none of them pleasant. Imagine having to spend all that time — some two weeks in all — in your brother’s cell, waiting for him to die. It was one of the worst experiences of his life.

The news was brought to Reg on the evening of 4 April — Charlie had died peacefully in his sleep at around 8.50pm that evening. Reg Kray was alone in his cell, alone in his thoughts — he was the last Kray standing!

He had already made his peace with Charlie earlier in the day, but it was a one-sided conversation — Charlie was so far gone that he couldn’t even manage the blink of an eyelid. He told him that they had not always seen eye to eye, that he was dissatisfied with some of the comments that Charlie had made. He told him that he hadn’t always been straight with Ron and himself — about the T-shirt deal, where he had kept all the money for himself; about the film deal, in which he accepted the unacceptable and paltry figure of £300,000 since he needed the money urgently to pay off his debts; about the problems it had caused when he was arrested for the cocaine bust, hence spoiling Reggie’s own chances of getting out on parole. Reg Kray had much to complain about, but through it all he bore Charlie no malice — they were family and that counted for much; now it could all be forgiven, once and for all time. There was more he would have liked to have said, personal things about the past and the present, but the circumstances weren’t right for such a conversation — being constantly handcuffed to two prison warders, always there and always listening, was far from the private, intimate environment necessary for such words.

But Charlie couldn’t hear him. He was fading fast and everyone knew it. His legs were now black, his breathing difficult — it was just a matter of time and, after 73 years time, was all Charlie had. The hospital had only recently issued a new statement to the press, saying, ‘He has had heart problems and respiratory problems. His condition is giving cause for concern.’

Reg had returned to Charlie’s cell, a lonely and embittered man. Soon he would be the last of the Krays — the sole survivor of the gangland wars, the ageing Godfather of UK crime. But, in reality, he was simply a lonely pensioner, waiting for death.

The rush to Charlie’s bedside was too late — he’d died. All the good intentions in the world would not bring him back. Reg couldn’t help his twin brother Ron, who had died at the hands of his beloved cigarettes, and he couldn’t help his older brother Charlie when he really needed help — before the cocaine deal and well before it had all started to go downhill, when Charlie’s son Gary died of cancer. This had been the turning point for Charlie — losing Gary was like losing his reason for living. He idolised his son, they were inseparable. But what made matters worse for Charlie was the fact that he couldn’t afford to bury him — Charlie Kray was broke, with little chance of employment, with only a few friends around him, with only a fearful dread of what the future held. It was Reg who had stepped in and saved the day, paying for all the funeral arrangements. But it was more than money that Charlie was in need of — he needed a reason to live.

The cocaine deal had been Charlie’s last hope, but doing a deal with undercover policemen was not the foundation needed for good things to come and a solid future. Champagne Charlie Kray was just an old time rogue, going nowhere — fast!

Reg wept and wept that first night. There was much to think about — the past, the present, the future. And there were the funeral arrangements to consider. Reg had pulled out all the stops for Ron’s funeral, five years earlier — should he do the same for Charlie? Or should he play it low key, and try to placate any inquisitive Home Office officials, keen to keep the last Kray in jail? He was urged by many to play safe — have a quiet ceremony with none of the pomp and circumstance that surrounded the funeral of his twin brother. But Reg Kray is no ordinary Eastender — he had already decided that first night in Charlie’s cell. It was to be the real McCoy, something to satisfy the fans, to remind people of the Kray legacy. Charlie Kray would be buried with honours — and everyone would know about it.

Reg couldn’t forget these past few weeks with Charlie. ‘I visited him twice a day, once in the morning and then a long session in the afternoon,’ he told the press, always eager to please. ‘He looked terrible,’ he told them, ‘he was just lying there on his back sucking in air from an oxygen mask. He was breathing really heavily and he was out of it.’ Reg paused for a moment. ‘It was heartbreaking, his chest was going up and down and he couldn’t hear me.’

But the crowds would hear, the East End of London would hear, the entire country would hear — from Reg Kray, as he laid on the accolades and praised his brother. ‘I’ve been through so much and, even though it has been hard coping with the loss, I have remained strong in mind,’ he told friends. ‘But it has been so sad to lose Charlie — prison was not the place for him, he was too old to endure it.’

The funeral service was held on Wednesday, 19 April, at Bethnal Green’s St Matthew’s Church. The idea was to bury Charlie, but it soon turned into a tribute to Reg. All the usual suspects were there — Mad Frankie Fraser, Tony Lambrianou, Freddie Foreman, even previous arch rival for the position of criminal boss of London, Charlie Richardson, turned up to pay homage. So too were the police — some 200 or more of them. They lined the route, checking the stretch limousines as they passed by, waiting for a sign of a break by Reg and seeing which villains they could identify among the mourners’ Who’s Who? But I for one definitely think that the two helicopters flying along the route, in the skies above the East End, was a wasteful way of squandering tax-payers’ money — and the marksmen, with guns at the ready was a little unnecessary — overkill comes readily to mind. There were more guns around the East End that day than there ever were in the days of the Krays.

The day started at English’s Funeral Parlour, where Charlie had been laid out like a king. He had lain in state in an open coffin, well-wishers coming and going, all paying their respects. Some brought wreathes, some best wishes for the afterlife — they paid their tributes to Charlie, one and all, as bodyguards watched over the lifeless body. In fact, there were more flowers in that funeral parlour than Buster Edwards used to have at his stall just outside Waterloo Station.

One wreath was in the shape of a boxing ring — it was fashioned from red roses and white carnations, coming from Reg and his new wife, Roberta. Another said simply ‘Grandad’ and yet another came from friends on C-Wing at Parkhurst Prison. The lovely lilies came from Barbara Windsor, with whom Charlie had had a fling back in the ’60s, and her new husband Scott Mitchell.

By around 11.00am, the villains were getting nervous — the collars were becoming tight. Reg was due any time now and those suits, last worn at Ron’s funeral, were beginning to feel the warmth of the day. But Reg arrived on time and everyone could breathe a sigh of relief. It was now Reggie’s show, and all the old lags and the new kids on the block could relax and enjoy the spectacle of a true East End send-off.

Wreathes and flowers piled up on the street and on the roofs of the stretch limos, as shadowy figures in shades got ready for the drive to the church. Charlie’s coffin was brought out and placed in one of the two hearses, the other was simply there for effect. They were ready for the ride, even the hearse carried wreathes spelling out the word ‘Gentleman’, and the crowds were lining the streets and hanging out of windows, craning their necks for a glimpse of the ageing gangster. Everyone appeared to have forgotten the fact that Reg Kray was a convicted killer.

The blue Mercedes people carrier, carrying Reg Kray and a woman police officer, handcuffed together, moved slowly down Bethnal Green Road. People cheered and threw flowers as the cortège passed by, stretch limousine after stretch limousine, some 18 in all. At a leisurely walking pace and spear-headed by a white-robed minister and a mourner, dressed entirely in black and complete with top hat, the cortège approached the church. They even managed to pass the top of Valance Road, where the twins had lived with their mother, Violet, and their father, Charlie Kray Senior. Reg caught a quick glimpse of the road, but he wouldn’t have recognised it — the houses had been pulled down many years ago and the streets are now clean of crime.

Gradually they neared the church, where enormous crowds had gathered. One by one the vehicles came to a stop, one by one the gangsters got out of their limos, one by one they entered St Matthew’s Church. It was all sombre and respectful, well staged and organised. It was just what Reg Kray had wanted — now he had full control of the situation. And he would give the crowd exactly what they wanted and expected.

He waved to the crowds and smiled when he reached the church even though he was still handcuffed to the policewoman, who towered above him. He looked thin and pale as he straightened himself, brushing down his grey pin-stripe suit and straightening his tie. His hair was almost white and cut short, and he looked frail. In fact, he looked like what he was — an old man.

There was plenty of muscle at the church to keep control of the crowds and there were Hell’s Angels present in abundance. As Reg entered the church, he was greeted warmly by the mourners, friends and family — all hugging and kissing in true Mafia fashion like there were no tomorrows. At last he was seated and the show could begin.

The coffin was brought into the church by six pallbearers to the tune of Celine Dion’s ‘Up Close and Personal’, a favourite of Charlie’s. All the gold and the jewellery on display glittered and sparkled as light entered by the main doors, a spotlight on proceedings, that were by now well under way. Even some of Charlie’s old showbiz pals were there — Billy Murray, who plays Detective Sergeant Beech in ITV’s The Bill sat quietly, head down in reflection, and Charlie’s old friend and drinking partner, the actor George Sewell, sat patiently and attentively following the course of events as they unravelled. These two were just onlookers this day, extras on the set — the star of this particular performance was Charlie Kray.

The ceremony was conducted with respect and aplomb by father Ken Rimini, who had known Charlie for many years. The songs included ‘Morning Has Broken’, ‘Fight the Good Fight’ and ‘Abide With Me’ — and there were enough heavies around to see that everyone sang, but everyone! The tears flowed and everyone stared at Reg, as father Ken spoke of Charlie.

‘Many things have been said about Charlie,’ he told the mourners, ‘some true and some very untrue and hurtful. I can’t judge him. He now stands before a greater authority than this life.’

As he continued, he told of the last time that he had seen Charlie Kray — at Charlie’s son Gary’s funeral, some four years earlier. Gary, a young man who would do no one any harm and a most cheerful character, just like his dad, had died suddenly of cancer at the age of 44. ‘It broke his heart,’ he told everyone.

Reg couldn’t hold back the tears as the good father spoke of his older brother, now deceased. He laid his head on the young shoulders of his wife Roberta as he tried to take it all in — the hurt, the frustration, the pride.

Tributes were read out loud from friends and family alike. Jamie Foreman, son of Kray cohort Freddie Foreman, told of how ‘Charlie’s smile will be engrained on my heart’ and others read poems in tribute. But the finale was a recording by Reg of a poem he had written for Charlie — it rang out on the speakers in the church, filling the air with nostalgia. His voice was weak, his tone sympathetic as he spoke the words.

‘I am not there, I did not die. I am a thousand winds that blow. I am diamond glints on snow.’

A true tribute from someone who many would call a diamond geezer, freed for the day from his prison home, to pay his last respects to his older brother — a man who had died without a penny to his name, a man who had made a pitiful living on the name of Kray, a fake and a fraud and a relic of bygone days. But Charlie Kray was nothing like his brothers — he was a crook, yes; he was a criminal, yes; he was a man who would do almost anything to make a dishonest living — but Charlie Kray was a loveable rogue, a charming womaniser, a cheerful and light-hearted soul who was always welcome company in any company. And I for one will miss him.

The oak coffin was led from the church to the sounds of one of Charlie’s favourite singers and old-time pal, Shirley Bassey. The sounds rang loud and true from the speakers, ‘As Long As He Needs Me’, as Reg leaned forward and kissed the coffin. The service was over — now to meet the crowds.

As he emerged from the church, Mad Frankie Fraser yelled out three cheers for Reg Kray. Naturally enough, the crowds were eager to comply and Reg had his tribute well rehearsed and planned — well worth the 50-minute wait. A few bear hugs later and he was once again back in the Mercedes and on his way to Chingford Mount Cemetery.

The four-mile trip was a formality. The crowds lined the streets, as they had done five years earlier. The procession of cars kept in line, orderly and calm — just like a military campaign. Once inside the cemetery, more heavies were there to protect Reg from the crowds as he wandered among the graves. A glance around the family plot lead him to the grave of Frances, his first wife, who had committed suicide at the age of 23. He stopped and stroked the headstone, waiting for the photographers to catch up with him. The policewoman, still handcuffed to Reg, took it all in her stride — she did her profession proud as she showed the kind of respect and consideration that many other officers would have found difficult to handle.

Flanked by the policewoman on one side and his present wife, Roberta, on the other, Reg Kray waited for the coffin to be lowered. As Charlie was laid to rest, Reg threw a red rose on to the coffin — a last, lonely tribute. Many hugs and kisses later, Reg Kray was ready for the journey back to Wayland Prison, Norfolk.

Diane Buffini, Charlie’s common-law wife, was one of the last to leave. ‘Charlie would have loved the sunshine,’ she told reporters, as once again the shouts rang out — ‘Free Reg Kray,’ and ‘Take the handcuffs off.’

Big Paul, the heavy in charge of the bodyguards, thanked the crowd for coming to support Reg Kray.

‘Reg wants me to thank you all for coming’ he told them. ‘He wishes you all well and he hopes to be among you soon!’

More cheers followed as Reg was led away to the blue Mercedes — it had been a long day, but the gangster, once the head of one of the most powerful criminal organisations in the country, had taken it all and more, and he was still fighting.

This fighting game is in the blood, as it was for all three Kray brothers. And with some 32 years behind him in jail and no date fixed as yet for his release, Reg Kray needed all the strength he could muster. Ron lost his fight back in 1995, Charlie had only recently lost his — so was Reg now to succeed where his brothers had failed? Could Reg survive to be set free, to stroll the streets of London once again — to be a celebrity, to be a man of stature, a man to be reckoned with within the society he scorned? Maybe that was the true meaning of ‘Fight the Good Fight’.

Colin Fry May, 2000