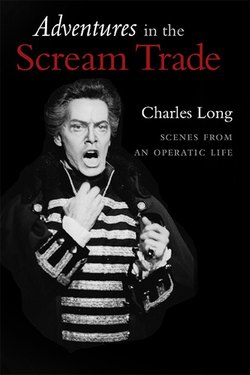

Читать книгу Adventures In the Scream Trade: Scenes from an Operatic Life - Charles Long - Страница 4

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Andante Con Moto Child Musician

ОглавлениеHave you ever wondered why a person, against the admonitions of his parents, would decide to go into music as a career?

It is often the case that American musicians arrive at their early musical experiences through a school or church affiliation—not at all unlike the early careers of Bach, Handel, Vivaldi, and countless others. So it was with me and most of my colleagues. I began as a woodwind player at age nine and continued with a variety of instruments until I auditioned for music school at eighteen, as both oboist and singer.

I remember the first time I held an instrument in my hands: a shiny black B-flat clarinet, a cylinder of lacquered wood with glittering, silver keys. It was one of the most beautiful things I had ever seen. Nature had endowed me with an embouchure more appropriate for the woodwind instruments than for brass. Percussion didn’t appeal to me, and, sadly, strings were not an option. There were no string programs in the schools nearby nor string players to teach them. Otherwise, I probably would have become a cellist.

I went home with the clarinet and a method book. My instructor expected me to decipher the first few pages by myself, but I didn’t have the slightest clue how to decode those cryptic symbols.

At the first rehearsal the other kids started to play, while I sat there looking bewildered. The instructor, a wonderful man named Clarence Ebner, asked me why I wasn’t playing.

“I don’t know how to read music,” I answered timidly.

This brought a hail of laughter from the others. Feeling like a dunce, I determined this would not happen again. I decided then and there to dedicate myself to this strange language of music.

I moved from clarinet to alto, tenor, and baritone sax. Then came flute, bassoon, and finally oboe. In this instrument I discovered an infinite beauty and more than enough repertory to keep me engaged for the rest of my life.

My oboe studies began with my first in a series of Italian mentors. Steve Romanelli played with the Pittsburgh Symphony. He also taught at Duquesne University and owned a music store nearby. He gave me lessons in exchange for my help around the store. After school, I worked the front desk, answered the phone, sold instrumental paraphernalia, and scheduled lessons for the several teachers. This was my first one-on-one experience with people who actually made music for a living. And what an eye-opener it was.

All the guys who taught in Steve’s studio were active in the music scene in Pittsburgh and part of an elite subculture of professional musicians that exists in and around every major city. The larger the city, the larger this community. Pittsburgh at the time had a symphony with a modest season, an opera company that mounted a few productions a year, a well-established summer stock company, and various clubs and cabarets. Not much work, only enough for a handful of musicians. Thus, the pool of local professionals was small.

So there I was, learning my craft from these working artists. I was in heaven!

At fifteen, in a desire to round out my musical education, I began piano and voice lessons and participated in community plays and school musicals as both singer and conductor/arranger. As is true for so many people drawn to the arts, this was a way for me to stand out from the crowd.

Good thing; I was never much of a student. My scholastic record was a constant frustration to my highly academic parents, so these previously untapped artistic inclinations provided redemption from outcast status in a realm where grades and achievement were everything. Exhortations of “You better get good grades or you’ll end up digging ditches!” rang in my ears. Only the music drowned them out.