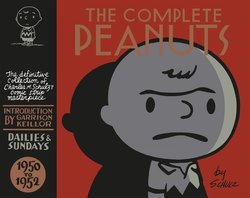

Читать книгу The Complete Peanuts 1950-1952 - Charles M. Schulz - Страница 299

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеBY DAVID MICHAELIS

On October 2, 1950, at the height of the American postwar celebration —an era when being unhappy was an antisocial rather than a personal emotion—a twentyseven- year-old Minnesota cartoonist named Charles M. Schulz introduced to the funny papers a group of children who told one another the truth:

“I have deep feelings of depression,” a roundfaced kid named Charlie Brown said to an imperious girl named Lucy in an early strip. “What can I do about it?”

“Snap out if it,” advised Lucy. This was something new in the newspaper comic strip. At mid-century the comics were dominated by action and adventure, vaudeville and melodrama, slapstick and gags. Schulz dared to use his own quirks—a lifelong sense of alienation, insecurity, and inferiority—to draw the real feelings of his life and time. He brought a spare pen line, exquisite drawing, Jack Benny timing, and a subtle sense of humor to taboo themes such as faith, intolerance, depression, and despair. His characters were contemplative. They spoke with simplicity and force. They made smart observations about literature, art, classical music, theology, medicine, psychiatry, sports, and the law.

They explained America the way Huckleberry Finn does: Americans believe in friendship, in community, in fairness, but in the end, we are dominated by our apartness, our individual isolation— an isolation that went very deep, both in Schulz and in his characters.

A lifelong student of the American comic strip, Schulz knew the universal power of varying a few basic themes. He said things clearly. He recognized the phenomenal number of small things to which the big questions can be reduced. He distilled human emotion to its essence. In a few tiny lines— a circle, a dash, a loop, and two black spots—he could tell anyone in the world what a character was feeling. He was a master at portraying emotion, and took a simple approach to character development, assigning to each figure in the strip one or two memorable traits and problems, often highly comic, which he reprised whenever the character reappeared.

Charlie Brown was something new in comics: a real person, with a real psyche and real problems. The reader knew him, knew his fears, sympathized with his sense of inferiority and alienation. When Charlie Brown first confessed, “I don’t feel the way I’m supposed to feel,” he was speaking for people everywhere in Eisenhower’s America, especially for a generation of solemn, precociously cynical college students, who “inhabited a shadow area within the culture,” the writer Frank Conroy recalled. They were the last generation to grow up, as Schulz had, without television, and they read Charlie Brown’s utterances as existential statements—comic strip koans about the human condition.

For the first time in panel cartoons, characters spoke, as novelist and semiotics professor Umberto Eco noted, “in two different keys.” The Peanuts characters conversed in plain language and at the same time questioned the meaning of life itself. They were energized by a sense of the wrongness of things. The cruelty that exists among children was one of Schulz’s first overt themes. Even Charlie Brown himself played the heavy at the start; in a 1951 strip, after prankishly insulting Patty to her face (“You don’t look so hot to me”), Charlie Brown scampers away, relishing the trickster’s leftovers: “I get my laughs!” But instead of merely depicting children tormenting each other, the cartoonist brilliantly used the theme of happiness—the warm and fuzzy happiness of puppies —as a stalking horse for the wrongness of things.

Peanuts depicted genuine pain and loss but somehow, as the cartoonist Art Spiegelman observed, “still kept everything warm and fuzzy.” By fusing adult ideas with a world of small children, Schulz reminded us that although childhood wounds remain fresh, we have the power as adults to heal ourselves with humor. If we can laugh at the daily struggles of a bunch of funny-looking kids and in their worries recognize the adults we’ve become, we can free ourselves. This alchemy was the magic in Schulz’s work, the alloy that fused the Before and After elements of his own life, and it remains the singular achievement of his strip, the source of its universal power, without which Peanuts would have come and gone in a flash.

It’s hard to remember now, when Snoopy and Charlie Brown dominate the blimps at golf tournaments instead of the comics in Sunday papers, that once upon a time Schulz’s strip was the fault-line of a cultural earthquake. Garry Trudeau, creator of Doonesbury, who came of age as a comic strip artist under Schulz’s influence, thought of it as “the first Beat strip.” Edgy, unpredictable, ahead of its time, Peanuts “vibrated with ’50s alienation,” Trudeau recalled. “Everything about it was different.”

A generation before Peanuts, the comics parodied the world. Schulz made a world. He lured mainstream newspaper comics readers into a dystopia of cruelty and disappointment and hurt feelings. His characters demonstrated daily that we are all, closely examined, a bit peculiar, a little lonely, a lot lost in a lonely universe; and being aware of that and living with it is life’s daily test.

“Nobody was saying this stuff, and it was the truth,” said Jules Feiffer, whose drawings in the late ’50s, like Schulz’s, were steeped in a new humor of truth called “egghead” humor. “Nobody was doing this stuff. You didn’t find it in The New Yorker. You found it in cellar clubs; and, on occasion, in the pages of the Village Voice. But not many other places. And then, with Peanuts, there it was on the comics page.”’

Feiffer, the melancholy Jewish intellectual striking at the heart of life as we knew it, saw in Schulz a fellow subversive. Their styles and audience could not have been more different. Feiffer aimed for an elite, urban audience; Schulz was drawing for everyone everywhere. But their territory overlapped. In a Feiffer cartoon of the late ’50s, a teenager enumerates the horror of middle age: getting stuck in a marriage, living in the suburbs, dying of boredom. A man confronts the teenager: “Why don’t you just grow up?” The teenager replies: “For our generation a refusal to grow up is a sign of maturity.” That was the message of Peanuts, too. Schulz was drawing the “inner child” many years before the concept emerged in the popular culture.

The Peanuts gang was appealing but also strange. Were they children or adults? Or some kind of hybrid? What would push real children to the breaking point, Charlie Brown handled admirably and without self-pity or self-congratulation. What would reduce children to tears in the real world was routinely endured in Peanuts.

In their early years, the characters were volatile, combustible. They were angry. “How I hate him!” was the very first punch line in Peanuts. Charlie Brown and his friends could be, as the cartoonist Al Capp said, “mean little bastards, eager to hurt each other.” In Peanuts, there was always the chance that the rage of one character would suddenly bowl over another, literally spinning the victim backward and out of frame. Coming home to relax, Charlie Brown sits down to a radio broadcast whose suave announcer is saying, “And what, in all this world, is more delightful than the gay wonderful laughter of little children?” Charlie Brown stands, sets his jaw, and kicks the radio set clear out of the room. Here was a comic strip hero, who, unlike his predecessors Li’l Abner, Dick Tracy, Joe Palooka, or Little Orphan Annie, could take the restrained fury of the ’50s and translate it into a harbinger of ’60s activism.

On the one hand, the action in Peanuts conveyed an American sense that things could be changed, or at least modified, by sudden violence. By getting good and mad you could resolve things. But, on the other hand, Charlie Brown reminded people, as no other cartoon character had, of what it was to be vulnerable, to be human. He was even, for a time in the ’50s, called the “youngest existentialist,” a term that sent his determinedly unsophisticated creator to the dictionary. The experience of being an Everyman—a decent, caring person in a hostile world— is essential to Charlie Brown’s character, as it was to Charles Schulz’s. The quality of fortitude (one of the seven cardinal virtues in Christianity) is at the heart of Charlie Brown. Humanity was created to be strong; yet, to be strong, and still to fail is one of the identifying things that it is to be human. Charlie Brown never quit, which in the end would prove to be a perfect description of Charles Schulz. Charlie Brown is a fighter, but a fighter in terms of pure endurance, not in terms of working out strategically how he is going to win. He simply endures; he stays longer on the baseball field than all the other kids. When the field is flooded in a downpour and only the pitcher’s mound is above water, he remains. His strategy is simple: hang on. He does not go off, as Ulysses does, to seek and make a newer world. Charlie Brown never makes it new. Snoopy, an animal, makes it new. Snoopy is somehow or other always new. Real imagination is allowed only to the non-human character in Schulz’s world. This tells us something: that the children are admirable for their human dignity and their lack of self-pity. Charlie Brown may feel sorry for himself but he gets over it fast. He is ennobled by how well he handles being disappointed. He never cries.

The moment when Peanuts became Peanuts can probably be marked at several spots on Schulz’s 1954 calendar, but nowhere more clearly than Monday, February 1: Charlie Brown is visiting Shermy. He looks on, bereft, as a smiling Shermy, seemingly unaware of Charlie Brown’s presence, plays with a model train set whose tracks and junctions and crossings spead so elaborately far and wide in Shermy’s family’s living room, the railroad’s complete dimensions cannot be shown in a single cartoon panel. Charlie Brown pulls on his coat and walks home. Finally, alone in his own living room, Charlie Brown sits down at his railroad: a single, closed circle of track, no bigger than a manhole cover. But there is no anger, no self-pity, no tears—no punch line—just silent acceptance. Here was the moment when Charlie Brown became a national symbol, the Everyman who survives life’s slings and arrows simply by surviving himself.

We recognize ourselves in Charlie Brown—in his dignity despite doomed ballgames, his endurance despite a deep awareness of death, his stoicism in the face of life’s disasters—because he is willing to admit that just to keep on being Charlie Brown is an exhausting and painful process. “You don’t know what it’s like to be a barber’s son,” Charlie Brown tells Schroeder. He remembers how it felt to see tears running down his father’s cheeks when his dad read letters in the newspaper attacking barbers for raising the price of a haircut. He recalls how hard his father worked to give his family a respectable life. By the fourth panel, Charlie Brown is so upset by his memories that he grabs Schroeder’s shirt with both hands and screams, “YOU DON’T KNOW WHAT IT’S LIKE!!”

SCHULZ DID. A SHY, TIMID BOY, A barber’s son, born on November 26, 1922, “Sparky” Schulz—nicknamed for the horse in Barney Google—had grown up from modest beginnings in St Paul, Minnesota, to realize his earliest dream of creating a newspaper comic strip. The only child of devoted parents, neither of whom had gone further in school than the third grade, Schulz linked the un-sophistication of his childhood home with the ideal of a dignified, ordinary life that he forever after tried to return to. “There are times,” he wrote at fifty-eight, “when I would like to go back to the years with my mother and father. It would be great to be able to go into the house where my mother was in the kitchen and my comic books were in the other room, and I could lie down on the couch and read the comics and then have dinner with my parents.”

But growing up was a dismaying process for Schulz. He felt chronically unsupported. “He always felt that no one really loved him,” a relative recalled. “He knew his mom and dad loved him but he wasn’t too sure other people loved him.”

His intelligence revealed itself in the second grade. In a class of thirty-one pupils, Charles Schulz was singled out as the outstanding boy student. Two years later, the principal at the Richards Gordon Elementary School in St. Paul skipped Schulz over the fourth grade. By the time he reached junior high school, he was the youngest, smallest boy in the class. He felt lost, unsure of himself. With no one to turn to, he made loneliness, insecurity, and a stoic acceptance of life’s defeats his earliest personal themes. At the same time, he possessed a strong independent streak and grew increasingly stubborn and competitive as life and its injustices, real and imagined, piled up.

As a slight, 136-pound teenager, with pimples, big ears, and a face he thought of as so bland it amounted to invisibility, he had few friends at school. In practically every thing he did at St. Paul Central High, he felt underestimated by teachers, coaches, and peers. No one ever gave him credit for his drawing, or for playing a superior game of golf. “It took me a long time to become a human being,” he once said. “I never regarded myself as being much and I never regarded myself as being good looking and I never had a date in high school, because I thought, who’d want to date me?”

Sensitive to slights, he never forgot the rejections of Central High. To the end of his life, he remained baffled that the editors of the Cehisean, the Central High yearbook, had rejected a batch of his drawings. At the age of fifty-three, he made sure that a high school report card was printed in facsimile in a collection of his work “to show my own children that I was not as dumb as everyone has said I was.” He projected the traumas of his adolescence far into adulthood—far enough, in the end, to see them become a crucial element in the universal popularity of his art.

Chronic rejection and unrequited love are the twin plinths of Schulz’s early life and later work. Even when he had become the one cartoonist known and loved by people around the world, he could still say, with conviction, “My whole life has been one of rejection.”