Читать книгу Drifting South - Charles Davis, Charles Davis B. - Страница 5

ОглавлениеChapter 1

Harrisburg Federal Penitentiary June 16, 1980

“You’re not out yet, Henry. Well, keep that in mind, yep,” he said.

The guard behind my left shoulder—the head goon who ducked through doorways and always walked behind prisoners with my kind of history—tapped me on the right shoulder with his stick. Tapped probably ain’t the right word. He hit me with it not hard enough to leave a mark a day later but hard enough to where I’d feel it a week later, whatever that word is. I was used to him walking behind me, and had come to know his stick in a personal kind of way. My head had put a few dents in it.

Officer Dollinger always ended everything he said with the word “yep,” and he was letting his stick tell me that I’d been mouthing off too much to a new guard walking in front of me.

Anyway, the head of the beef squad behind me had never called me Henry before. It seemed the whole bunch of them would come up with new words to call us every few years, same as we’d come up with new words to call them. Lately the guards called all of us convicts either Con or Vic.

Don’t see that in movies, prisoners being called Vic. Don’t see a lot of things in prison movies, at least the ones they’d shown us in prison, that actually make being locked up look and sound and smell like what it is, which is similar but different in an uglier, more crowded, louder, smellier way.

But mostly the guards just called me and the rest of us “you.” After I’d learned to write, I’d signed so many of their forms over the years with that name.

You.

But in D Block, Pod Number Four-B of the Number Nine Building known as the Special Housing Unit of Harrisburg Federal Penitentiary, the few pards I trusted with some things but not all, and had become friends with as much as you can in a place like a prison, called me “Shady.”

At some point in some lockup or lockdown, I was feeling dangerous lower than is good for a man to feel, and I decided I might need something to remember who I used to be before I had to live behind tall walls and wire, even if I couldn’t feel that way no more. On my last day in prison, both of my arms were covered in fading blue ink, pictures and words. Those prison tattoos read like a book of my youth, and across my back and shoulders in big letters was the word “Shady.” It was the first thing I’d ever had scratched into me. Nobody knew what Shady meant because I never told anybody about my past or what little I knew of it, but it came to be what I was called by the other inmates.

So anyway, given a kind warning by stick standards, I decided to not say anything more to the new jug-head guard in front of me. I just kept shuffling slow and steady, wearing irons on my ankles that I’d gotten used to so much that I’d grown permanent calluses from them. I kept shuffling slow and kept my bearing about me as I tried to ignore the irksome clanking of the chains at midstep, because it wouldn’t do me well to raise hell about any of it.

I’d already been through eight hours of a hurry up and wait drill, first in my empty cell with a rolled-up bed, and then sitting outside the warden’s office watching the guards keeping an eye on me over top issues of Life, Field & Stream and National Geographic magazines.

An old trustee with heavy glasses on and small shoulders who seemed to have been there before time began and a man who I’d always gotten along with somewhat tolerable came in to say at long last that the head man of the Harrisburg Federal Penitentiary was busy attending to a bunch of local politicians touring the place.

All of the guards laid down their aged magazines, bored, like they’d probably done a thousand other times, and then they grabbed me up and escorted me to another waiting room. After I watched them sip on cold bottles of pop for another hour, I finally had my farewell talk with the assistant warden.

The tall shiny wooden sign sitting on top of his desk yelled that his name was Theodore Donald O’Neil, the Third. And he was young, a good bit younger than me, and I wasn’t that old. He seemed proud of himself sitting behind his long name and polished oak desk in a way a young man is until he’s really tested and finds out what’s really inside of him.

But like this old Chinese lady had come in to teach us once, I kept focusing on my breathing. I took in air slow like it was the gift of life and let my lungs fill up with the gift before letting it out, just as I’d done over and over from years of trying to let out what was about to make me explode, or eat my insides away to nothing.

The assistant warden told me to sit.

I sat.

He looked so serious, and then he grinned.

He leaned back carrying that grin and stared as hard as he could for what seemed a decent long time until his eyes started to get watery.

“If it were up to me, you wouldn’t be leaving. I’ve scanned your file and sitting here looking at you, I know you’re still a threat to society. It’s written all over your face.”

I kept staring at him because my eyes had dried up years ago when something deep down in me turned the water off, and I could now stare at anybody until I just got so bored with it that I’d decide to stare at something else. It was written all over Mr. O’Neil that he wasn’t quite yet the hard man he’d need to be in this new job, as his eyes left mine and he began talking again and fiddling with a pencil that had teeth marks on it.

“Besides not making parole several times for various violations, you’ve been involved in several serious altercations. You even managed to kill an inmate here.”

“I’m sure it’s in the file what I did and why,” I said.

“Actually, the file only has your version of what happened, being the other man is dead.”

“I had to defend myself if I wanted to keep living is the short of it.”

“Yes…you never did say why the man tried to kill you, as was your story.”

“Don’t know.”

He looked over the papers at me. “Well, we can’t ask his version of what happened, can we?”

“You could dig him up but I suspect he wouldn’t say a whole lot,” I said.

He kept looking at me for a good spell, then at the head guard before he eyed his watch. Then he turned his attention square back at me.

“The warden doesn’t have any other recourse than to let you go. I’d like to believe that you’ll begin leading a decent life, but your nature toward violence will lead you right back into incarceration, if you don’t get killed first, of course. But you’re a hard man to kill, aren’t you, Henry Cole?”

“This damned place hasn’t killed me yet.”

“This institution didn’t try to kill you, it tried to rehabilitate you. And we failed in that task. The taxpayer’s money has been wasted in that regard. You are living, breathing proof that some men cannot change their behavior, and therefore they should be restrained and kept from society that they will naturally prey on and do harm to. It’s my opinion that you should be kept here for as long as you have the capacity to continue to be a threat to others, which would be until you are either a feeble old man or until you die. But as you know, even though you still have evil in your eyes as you sit there staring at me, I lack the authority to keep you here and throw away the key, as they say. I did want you to know my feelings on the matter, however.”

I couldn’t hardly stand to be quiet anymore with that young man with not a scar on him judging me the way he was doing, but I kept trying to sit on my temper best I could. It was starting to catch my ass on fire.

“What’re your plans?”

“Don’t have any,” I lied.

“None?”

“Not a single one,” I lied again.

“What do people like you think about in here for…what was it…eight years?” he asked.

“I’ve been here a lot longer than eight years.”

“Didn’t you ever think about what you would do when you were released?”

“What do you think about in here when you’re locked up behind the same rusty bars as I am, day after day?” I asked back.

The assistant warden tried to grow another grin but it slid away.

“I can leave here whenever I want. You can’t. But to answer your question, I think about how to make sure predators like you stay here where you belong,” he said. “It’s very, very satisfying.”

He looked like he meant what he said, and I respected him more than I did when I’d first laid eyes on him, but still not much. He went back to scanning and flipping page after page of I guess what amounted to my life in prison, which amounted to all of my adult life. He stopped to read one section with a lot of care.

“You’ve been housed in protective custody most of your time here. Why?”

I didn’t say anything as he kept reading. He finally looked up.

“Why the attacks?”

“If it ain’t in there, I don’t know,” I said. “I was actually hoping you might.”

“You don’t know why inmates on two other occasions tried to kill you?”

“I didn’t even know them.”

“This is a complete waste of time.” He closed my file and threw it onto a stack of other files.

I noted mine was the thickest and an old pain shot through me in a thousand old places.

“The reason we received the order to release you two days early is certainly not because of good behavior, it’s because the Bureau of Prisons has red-tagged you a security risk. The unannounced change of date reduces the threat of another violent incident just before, or on, your actual court-order release date. Do you understand what I’m saying?”

I nodded.

“Your file reads that either you have a very difficult time playing with others, or someone has wanted you dead for quite a long time. If it’s the latter, we would rather that not happen on our grounds, especially the moment you walk out of the gate unprotected. You will be a standing duck for anyone who may have been waiting for such an easy opportunity. It’s happened before and we don’t need the mess or paperwork.” He started showing what looked like his first real smile. “Your safety will very soon be your own responsibility. I do wish you good luck with that.”

He acted like he was waiting for me to say something. I couldn’t think of anything to say besides wanting to tell him that if the guards were to leave, I’d probably try to mop the buffed floors of his office with his face to get rid of that real smile and the smirk I’d had to stare at. He was lucky because if it were just another day and I had a ton more time to pull, I’d try it even if I was chained up with guards all around me. I’d get one lick in for sure somehow that he’d carry with him for a long time, and maybe he wouldn’t smirk at and talk down to the next man sitting in front of his desk who’d pulled his time. He definitely wouldn’t smirk at me again.

I kept staring at young Mr. O’Neil, thinking how three months in isolation and catching another charge for assault on a federal officer and two more years on the tally is worth every minute of it, every now and then.

But not that day.

Hewas lucky. And I figured that Iwas lucky, too, because my better nature was in charge of me sitting before him. The nature I’d known as a boy. He finally asked if I had any questions.

I leaned forward as far as I could and shook my head.

He shot up all of a sudden. “You won’t be out for long.” He then nodded at Dollinger, and that’s when I could feel being let free. I could feel it all over me like I was standing under a waterfall. It made me nervous, and that was a feeling I hadn’t felt since I didn’t know when. It hit me at that moment how long it had been since I’d felt anything at all except rage or rainy-day late-morning hollowed-out lonesomeness.

The guards stood me in an elevator, facing the back of it, and we went down to the bottom floor of that building and when the doors opened, we all walked like a formation again into a bright room that looked like a poured concrete box. Wasn’t anything in it that wasn’t colored gray. Even the prison clerk behind the counter wore a gray uniform and he must’ve been down there so long, his face had taken on the same colors of the walls and file cabinets.

“What hand you write with?” the stump guard beside me asked.

I raised the first finger on my left hand and he took off the one cuff from it, and then cuffed that bracelet through an iron ring mounted onto the top of the long counter. One of the older guards behind me took off the leg irons, being careful to stand clear in case I bucked.

I looked over my shoulder and made sure he was out of the way, then I stretched and shook out the cramps in my legs as the clerk handed me a pen and shoved paper after paper in front of me to sign while telling me what I was signing. But I’d learned to read and write, probably the only good things I did learn in prison, and even though I was in a hurry to get out of there, it looked like they were in a bigger hurry than me to finally get me out-processed. I saw on the clock that it was shift change.

I decided to take my time reading those papers. I read careful and signed every single sheet with the name “Shady.” They’d been kicking me all day long. I figured I’d get in one last kick from Henry Cole.

“Where’s my belongings?” I asked.

The clerk bent down and pulled up a wire basket that held a big paper sack. He dumped the sack onto the counter. A button shirt, dungarees, old drawers, white socks and a pair of withered-up brown shoes lay in a heap. Uncle Ray’s revolver wasn’t there as I surely knew it wouldn’t be, and the razor and whetstone and Ma’s roll of money were gone, too. But it made me want to smile seeing the clothes because I could remember wearing them. It made me feel young in spirit for one of those too-fast seconds you try to grab hold of but the next second it’s off on some breeze.

I didn’t want the clothes to wear, knew they wouldn’t fit and I figured it might be bad luck anyway to put on clothes with sewn-up bullet holes, but it was nice seeing them because they brought back a feeling of better times. I did need the shoes because I figured there was still a ten-dollar bill sewed between the sole and the bottom leather for just such a predicament, as Uncle Ray had taught me when I was a boy in Shady Hollow, just before he’d gotten killed.

I ran my one free hand through everything, checking careful and hoping with all the hope in me to find a folded piece of pretty yellow paper with her handwritten words and scent on it. Amanda Lynn’s letter to me. Feeling through that pile of old things, I was afraid that it hadn’t made it through all of those miles and years. But I looked and kept looking, because if by some chance it had survived such a journey, I was going to be certain right then about locating it. I kept feeling for it, not paying any mind to anything else. It was the letter she’d given me in Shady Hollow, the same one I’d never gotten to read, and the same one that was taken from me after a shoot-out years before, and before I’d even learned how to read. I could read now, but that letter and whatever was in it was as gone and still as big a mystery to me as she was. The scent of her was nowhere in that dumped basket of old things, either. All of it just smelled like the sort of dust that only collects in a prison.

“What’re you looking for?” the clerk asked.

The quiet noise of his voice sounded like a slamming door to me. I gave up my search, stared down at the truth before me, grabbed the shoes and clothes and threw them back in the bag. I took hold of everything in my one uncuffed hand, then after I’d signed the last of the paperwork and it was official that I was a free man, they uncuffed my other one.

“Want to throw those clothes away?” the clerk asked.

“They’re mine and I’m taking them,” I said.

Just like I knew I could give that young assistant warden sass and the one green guard some serious mouth, I could surely speak to that clerk like a man would to another man and not get in a bad way about it. I felt like saying more, and I would’ve said more with so much battery acid still going through me, but he’d treated me fair and seemed all right.

I could’ve raised a lot more ruckus than I did that long day and gotten away with it. I wasn’t getting out on parole. They’d denied me that three times. I knew, too, as much as I was glad to be getting out of there, that some of those guards were glad to get rid of me, so I didn’t expect any trouble from them. It’d been a long twenty-one years on both sides of the bars in the two prisons I’d been in.

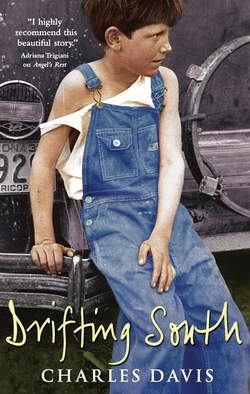

Around five that evening, I walked through the yard toting my paper bag of all I owned in the world, and with no steel on me anywhere. I had on a nice suit of clothes that the prison issued me, blue pants and a white shirt, stiff black shoes and a canvas tan jacket. In my pocket was fifty dollars of state money, and a bus ticket to Wytheville, Virginia. Ma was on my mind heavy at that big moment.

She’d told me from the time I was a little boy I’d grow up to be a wealthy, powerful man, and that I had a true good nature hiding amid the boy mischief in me. She also told me that one day I’d use that wealth and power for the good, because I’d outgrow the bad and all that was left would be the good. But I never could figure why she’d say such things, except maybe that was the sorts of hopeful wishes all ma’s say to their young’uns.

On my last day in prison and with so many things working in me, I knew for certain I’d turned out not to be any of those things, especially good. I’d turned out to be no good account at all…an apple knocked from a tree limb when not half-ripe, then left on the ground to do nothing but rot slow and turn dark from the inside out. I figured if I’d turned out to be anything, I was maybe just an old name in some worn-out old story told in the beer halls of Shady Hollow.

Somehow I’d aged behind gray prison walls to be almost as old as Uncle Ray was when he died. That hit me hard on the morning of my release. I didn’t know if he was a good man, but he was a far better man than I’d ever turned out to be, and he’d passed so young in such a bad, bloody way trying to protect me.

I never expected many visitors or letters or anything like that while I was locked up. Most of the people I was close to couldn’t write and didn’t have the means to up and travel to prisons for visits, plus most of them steered as far from them as they could anyway. But I did expect to hear from a few, like my ma and my brothers, and maybe even Amanda Lynn. Just maybe. I don’t know why, but every night I hoped to hear something from her that next morning, but that next morning always was exactly like the sliver of a fast-fading golden streak on a double reinforced concrete wall morning before it. I never heard from nobody, and my worries over it grew every year, but I kept trying to tell myself things like it was because they wouldn’t know the name that I’d been going by for so long, and they were having a hard time locating me.

But even trying to believe in that reason, Shady Hollow would’ve gotten some wind of what had happened to me. Had to. And they would’ve known I wouldn’t have given the police my real name of Benjamin Purdue all of those years ago.

I was raised better than that.

Ma had to know where I was, I was almost sure of it, if she were okay and nothing bad had happened to her after I’d left. She’d know where I was, I kept telling myself, probably just like some of the religious prisoners I’d known believe Jesus always knows where they’re at and he’s listening to the prayers that they mutter asking for the same old important tired things and important worn-out blessings over and over while trying to fall asleep.

Ma wasn’t some God or some God’s perfect son in some fancy black book that you best never disagree or quarrel with too much, though. She was real. She was as real as the bars in my prison cell or as real as the feel and look of a sunny day long ago in a place I’d seen through young eyes, not through bars. She was real, and she’d told me that she’d find me, and that I could never ever come back home until she did, when it was safe.

At the end of serving my state and federal time, I was thirty-eight years old, tall and convict lean with a head of hair still dark as Ma’s, and a ponytail fell halfway down my back.

I’d changed so much in prison that I figured quite a bit had changed in Shady Hollow. Not just the looks of me or the looks of that lost place, but the stuff inside of both of us. I hoped it wasn’t all hollowed out and hadn’t gotten as mean and hard as I had over those years. I wondered if even my own ma would recognize me. Almost all of Benjamin Purdue got killed a long time ago. I didn’t just go by the name Henry Cole now.

I was Henry Cole.

My whole life was still one awful, empty mystery. On my very last day locked up, I had a lot of reasons and questions and especially darkness inside of me—old wounds that had never healed up right, and a lot of other things I couldn’t even put to words—calling me back home.

But I guess the first thing calling me back was that sometimes a person just needs to go to his roots and see old faces that knew you when you wore a different face…a face with a smile on it that only a young man who thinks he’s got the world by the tail has. Sometimes a person just needs a thing like that in a real bad way. To go back and try to grab back hold of something you once had, and had felt the missing of it every day since. Then maybe some repairs could be made to some things.

Just maybe.

I was twenty-one years older than the day I’d gotten arrested, and as I was about to take my final steps toward being a free man, the last thing I cared about was whether it was safe or not to go back to Shady Hollow. I didn’t have a care if I died once I got there.

I was finally heading back home.

Home.