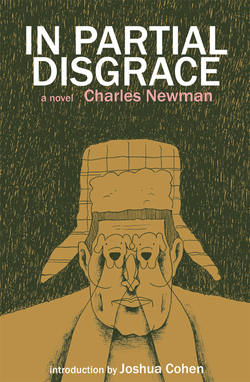

Читать книгу In Partial Disgrace - Charles Newman - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIN DARKEST CANNONIA

(Rufus)

I fell into that hermit kingdom carelessly, the chute shuddering above me as the shroudlines cut my hands. Below, the rivers rested in their courses, like wine from a broken urn; above, the stars ran backward in the upper air. Cinching up my harness, I drifted trembling toward the signal bonfire and my contact—a man apart, devoted to his mission, whose realm would become my destiny, as ours would be his fate. But buffeted by cruel crosswinds, blows from the powers of the air, I was dragged toward shores of black milk, skipping like a stone through the dark and empty land. Palms turned to the stars, I cursed my gods, mentally settled my affairs, and muttered an incoherent prayer: Give me your hand.

Grinding teeth and bloodied mouth a howl, I made out two horrific shapes hurtling toward me, two spotless dogs drawing near with unimaginable speed. One attacked the chute, deflating the billowing silk beneath his body; the other was in the air above me, all red mustachios, golden eyes, and ivory fangs. Was I to be saved from death by drowning only to be torn apart by devil dogs? We rolled and wallowed, my lapels in the brute’s jaws, until we finally came to rest, his forepaws crossed upon my chest, rearquarters raised up, cropped tail awhirr. And then, wise in his negligence, he ringed my ears with openmouthed kisses.

Their master was soon beside us, a giant of a man in a shepherd’s cloak, a conical fur hat concealing his face, and wielding a staff at least ten feet tall. I prepared myself for the blow. Then the cloak parted like a theater curtain, revealing only a wiry boy’s boy very near my own age, standing upon stilts within the felt greatcloak and unremarkable save for his salient gray eyes, the left one half-closed.

The dog stepped off me to join his mate, who trotted up, a bit of parachute silk in his flues, his red beard full of cockleburrs. They seated themselves on either side of Iulus, barrel-chested, taciturn, with heart-shaped buttocks and slightly webbed feet. A handsome brace of superior spirits, radiating the same unpretentious dignity as their young master, even down to the half-closed eye; sly and unsentimental, neither obsequious nor shy.

Their coat, as their breeding, was like nothing I had ever seen in the animal world. A wiry texture, neither harsh nor loose, dark red bristles folded flat across a softer golden undercoat, changing its cast with every modulation of the moonlight. Their squared-off heads sported trim mustachios and goatees, brownish-pink lips and noses, and their immense ocher eyes were garnished with wispy eyebrows. When they shook their heads, the flapping of their ears sounded like distant machinegunfire, and it was only later that I noticed the detailed conchlike enfoldment of their inner ears, their only vulnerability, designed for the worship of natural sounds. And then, each with a single golden peeper trained on me, the dogs allowed their tongues to carelessly loll from the corner of their mouths, as if to say: “You see! One can be great; and amusing!”

We put away the chute and the shepherd’s disguise in a hollow tree, buried my shortwave and silver dollars, and walked through the night without a word. It seemed our contact could not have been otherwise; we were of that age that requires no password.

I was in a zone of pure existence, which I would not experience again until the tremors of old age. Part of me was still pasted in the sky, part of me ambled along the unsafe earth, illuminated by faint and mocking stars. And part of me was observing all this from an unknown vantage, calm and imperturbable. Yes, give me your hand.

In Cannonia the dawn is striped. Between great sliding plates of slate and amber in the nervous sky a pallid sun appeared, diffuse and shapeless as a ball of Christmas socks. What I had upon first impact thought to be a carpet of fir needles proved to be a unique ground cover, impervious to frost or scorching. Neither heath nor grass nor legume, but firm and pliant kidney-shaped leaves with stemless white flowers, each large enough to hold a dewdrop, each footfall releasing a strong and refreshing aroma. If one stumbled, there was not the slightest sound, as if we were traversing a great expanse of silent pride which could absorb the rudest insult. Indeed, as I often saw that morning, the ground was so forgiving that bombs often did not explode on impact, but merely buried themselves up to their tailfins, scattered about the landscape like giant clumps of gray-green crocus.

The dogs cast out from us in great looping figure-eights, apparently indifferent to game and involved solely in their role as escorts. Once an immense Icarian crane went up between them in an hysterical imitation of flight, but they paid no more attention to it than if it were a gnat. It was hard to say if their originality or their manners were more impressive.

In an effort at conversation I inquired about their origins. My contact glanced through me, smiled slightly, then gave a transparent shrug, indicating that this was not the time or place for such a long and problematic discourse, and implying that the dogs were only a kind of theme in a larger drama over which we had already lost control. So I changed the subject to the smell of the earth, a bruised tang something between pineapple and spruce, an aroma more incensed than any I had experienced.

“Ah, yes,” he spoke for the first time, wrinkling his nose. “Most of Europe smells of seaweed.”

“A seacoast can come in handy,” I bantered.

“Oceanus is a nullity,” he sniffed. “If a sea should be required,” he added more mysteriously than nicely, “it can always be brought onstage in the actor’s eyes.”