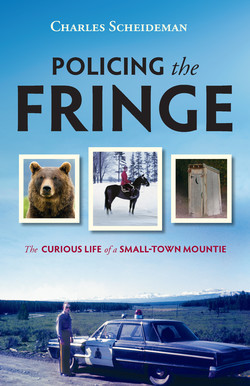

Читать книгу Policing the Fringe - Charles Scheideman - Страница 4

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCar Chase at Kicking Horse Pass

This story begins on a beautiful summer morning on the highway leading from Revelstoke toward Golden and the summit of Rogers Pass. A small two-seater sports car, a Fiat Spider, had caught the attention of everyone on the highway with extremely erratic driving. The little car was reported to be using the left side of the highway more than the right, cutting corners, passing in unsafe locations, and then slamming on the brakes very close in front of other traffic. The only person in the car, a young man, was constantly waving his arm out the driver’s window and flashing the peace sign. Several motorists stated that they thought he favoured large transport trucks for his “cut in and brake” stunts. They felt he was suicidal.

The summer traffic volume did not allow for continued high-speed driving, but it also appeared that this driver was not intent on high speed alone. He drove very fast at times, but he also frequently slowed to speeds that severely restricted the normal flow of traffic. This erratic behaviour created a blockage of eastbound vehicles more than a mile in length. The westbound traffic was only affected briefly when the offending vehicle was in their lane forcing them to take evasive action by braking or swerving to avoid head-on collision.

Reports of the erratic driver began to reach the RCMP in Revelstoke and the Park Warden Service at Glacier National Park headquarters at the summit of the pass. The primitive police radio system that served the Rogers Pass highway corridor at that time only allowed communication between the summit area and the police office in Revelstoke. Police and Parks radio signals went to a location at the summit where they were switched to a telephone link and carried to Revelstoke by wire. This non-system was unreliable in the summer and all but useless in the winter when heavy snow interfered on a constant basis. There was no permanent police presence on the ninety-two miles between Golden and Revelstoke. Requests for police services went to the park wardens, who relayed the information to Revelstoke whenever the radio-phone link was operable. When police attendance was required for incidents east of the summit in the Golden RCMP area, the requests were manually put into another radio and telephone link between the Revelstoke police office and the one in Golden.

The mobile offender in this case was eastbound and over the summit of the pass before we in Golden received information that he was headed in our direction. We later learned that the information had been delayed in the system by about twenty minutes; a delay that could have cost lives.

Our follow-up investigation revealed some strange happenings. During one of the frequent slow-driving parts, the small car was caught behind a transport truck and forced to stay there by another transport driver who moved alongside. This happened in one of the double-lane sections of the highway, but the truck drivers were fast running out of room. When they reached the single lane ahead, they would have no choice but to allow the offender out again. Another trucker saw what was developing and he immediately moved his smaller truck in behind the sports car and completed the box. The truckers were able to communicate with their citizen’s band radios and they used them to great advantage. The lead truck began to slow, as did the other two. This left the sports car and driver in a very restricted place. He swerved desperately, looking for an escape, but the truckers were in no mood to accommodate him. As the four vehicles came to a stop, the outside truck moved to his right, leaving the little car so tightly positioned between the transport truck and the guard rail that the driver was not able to open either of his doors.

At the moment the citizen’s arrest was being executed, one of the park wardens arrived on the scene in an International Travelall four-wheel drive. The event should have been over. However, the arrival of the warden seemed to take the initiative away from the three truckers. They were glad to have the “authority” there to take over. I believe that if it had been left to the drivers for a few minutes longer, the result would have been different.

The warden approached the pinned sports car from the passenger side and spoke to the driver, who was still inside the car. The warden later advised that the driver was calm and in control of himself, and that he apologized to any and all present, saying he did not know why he had acted like that. The warden assisted him out of the car through the passenger window. When the offender was out of the car, he continued his apologies and even thanked the truck drivers for bringing him to his senses and stopping the danger he was creating. No one thought to secure and disable the little car. The driver was able to convince the warden that he was sane and remorseful and that he would make himself available to face any charges resulting from the happenings that morning.

The warden then shifted his attention to the long line of traffic that had built up behind the trucks. He left the offender standing beside the pinned sports car and began directing traffic. Soon he decided to speed up the clearing of the traffic and asked the truck drivers to move their vehicles so they only blocked one of the two uphill lanes. The lead truck had only moved a few feet ahead when the Fiat burst out of the box and sped away with the driver flashing the peace sign from his open window.

The warden ran to his vehicle and slowly set out in the direction the fast little car had gone. The International Travelall four-wheel drive was very useful in some circumstances, but highway travel or pursuit driving was most definitely not its long suit. The offender’s Fiat, on the other hand, was right in its element on the open highway. This fact was about to be very clearly demonstrated.

The parks vehicle was able to struggle up to a maximum speed of about forty miles per hour on the mountain grade while the sports car could make eighty or more. The pursuing warden never saw the offending vehicle again.

The forced stop had taken place only a short distance west of the highway summit. The pursuing warden immediately started the message intended for us at Golden, which began the tedious process of being relayed back to Revelstoke. Eventually we received enough information to conclude that the offender must be stopped at the first opportunity and decided to establish a roadblock on the Columbia River bridge between Golden and the east end of Rogers Pass. We needed about ten minutes to reach this ideal roadblock location, but we were about halfway to our planned destination when we met the little car and saw the driver waving the peace sign as he streaked past us. I was in the passenger seat of the police car; the driver was an experienced police constable and an excellent driver. We executed a skid turn and immediately pursued the Fiat, which was travelling at about eighty miles per hour. We immediately radioed this information back to Golden. There was only one policeman left at the Golden office and he made a desperate attempt to get to the highway with his police vehicle. We saw him near the highway as we flashed past on the main road.

The police car I was in was an extremely powerful Ford sedan with an engine that Ford designated The Interceptor. If this car was pushed for maximum go, it would shift out of low gear at sixty miles per hour and out of second gear at one hundred miles per hour. The man in the Fiat Spider had now met something to be reckoned with.

After we turned, we were in close pursuit of the Fiat within about one mile. We then saw firsthand how this person was performing. He drove on the left into blind corners and passed other vehicles with no regard for oncoming traffic. In the first mile that we were in close pursuit he came close to four or five very serious crashes. It was only the quick evasive actions of other drivers that prevented a catastrophe. We allowed a gap to open between us in the hope that he would use a little caution, but that seemed to make no difference to him. We were aware that the lone remaining RCMP member in Golden was trying to get to the highway junction before we did. However, the highway was more than four lanes wide at the junction and we knew there was little he could do even if he did get there. This guy was not going to stop for a flashing red light on a single police car.

As we entered the congested area of the highway near Golden, the Fiat was forced to slow and swerve through the traffic. The driver braked into a skid to avoid a crash and then geared down and immediately accelerated as hard as the little car could. We came behind with our lights flashing and the siren howling, expecting to see a crash at every intersection. We cleared the first business area along the highway and approached the main highway junction just in time to see our last chance for assistance still a quarter of a mile from where he may have been able to help. We shot by the intersection and started into Kicking Horse Pass, the section of the Trans-Canada Highway that was known as the worst ten miles of driving from one coast of Canada to the other.

We now felt that we had a small advantage. The highway was so winding that traffic was much slower than in the area we had just covered west of Golden. The pursued car had out-of-province license plates, so we were quite sure the driver was not familiar with the road and thought we would be able to push him into overdriving one of the many curves. At that point we would have welcomed the sight of him running off the highway rather than crashing into some other unit of traffic.

We held a small meeting to decide if I should try to shoot a tire off the car. The meeting was called to order. The secretary was absent. A question arose from the floor. SHOOT?? YES! TRY IT! All in favour? Carried. New business? None! I asked my driver to yell “clear” if there was no visible oncoming traffic and “hold” if there was. This motion was also carried by a unanimous vote.

I removed my seat belt and leaned out the passenger window of the big Ford. I had never fired a shot from a car but I was amazed how the car door and the flared fender supported my attempt. As we entered the second mile of very winding road we were in close pursuit. The little car had to slow greatly to get around the curves and it was very short of acceleration compared to our unit. At times we were so close behind the Fiat that I could not see the right rear wheel, which I had chosen as my target. I fired three shots over the next mile, each of which I felt could have done the job, but there was no visible effect. We then entered another very sharp uphill curve to the right. The little car braked hard to reduce his speed for the curve and as he came out of it he presented the side of the car to my vantage point. I could clearly see the right front wheel and I had the “clear” call from my driver. I shifted my point of aim to lead the front wheel and fired. Once more there was no visible result, but we were again tight behind the little car.

After the fourth shot we met oncoming traffic and I held fire. We pursued uphill for nearly half a mile with constant oncoming traffic until the next opening. I was about to take aim again when I saw smoke from the front of the little car. The thin wisp quickly became a cloud and we began to feel we had won. The Fiat was now in obvious trouble. It could no longer accelerate as it had in the previous miles and we could see chunks of smoking rubber flying up from the right front wheel. The driver continued to give it all he had over the next two miles, but his efforts were now futile. He was only able to generate twenty miles per hour or less. Suddenly the little car nearly disappeared in a cloud of steam as a hose burst and the contents of the overheated cooling system vaporized in an instant. This phase was over.

We bounded out of our car and pulled the screaming driver out of the Fiat. He now presented a very different attitude than he had when he was stopped one hundred miles earlier. He appeared to be terrified, and he pleaded with us not to kill him, all the while fighting us with all he had. He had lost control of his bladder. We were easily able to overpower him and we placed him face down and cuffed his hands behind his back. The moment we released our hold on him he rolled over and tried to kick us, but this was of no danger to either of us.

The other police car, which had overtaken us near the slow end of the chase, took the prisoner and returned to Golden. We waited for a tow truck to remove the car to secure storage. I examined the little car to see where my bullets had struck and found three bullet holes in a close group just below the right rear tail light. The bullets had penetrated the outer skin of the car, but then had hit the heavier metal of the inner fender and had not gone through. The right front tire was gone and the wheel was worn down until it would no longer turn on the axle. I examined the right side of the car from end to end but I was unable to find any indication of a bullet impact. We assumed my last shot must have penetrated the side wall of the tire. The flat tire then caused heavy resistance for the little car and the engine boiled and seized.

Any one of the first three shots could have flattened the right rear tire had I been in possession of a better firearm. Neither the issue handgun nor ammunition of that time was effective, and combined they were a bad joke. There were many superior firearm and ammunition combinations available but at that time the upper echelons of the Mounted Police were still looking for a nicer way to shoot someone.

Our prisoner had somewhat regained his composure by the time the car reached our lock-up in Golden. By then he was reciting the standard suspect line of, “I refuse to say anything until I have talked to a lawyer.” One of the members who had not been involved in the chase took him aside and advised him he would be held in custody until we were able to take him before a court the next day. He was offered the use of the telephone, but declined. Judging by our observations of his driving and his actions at the arrest, we were all of the opinion that we should have his marbles counted. We warned our civilian prisoner guard to be extremely careful with this man and to watch for a possible suicide. He was not to be let out of the cell unless there was a policeman present.

During the day that he was in our cells, his mood varied from hour to hour. He frequently screamed and ranted and rocked the cell cage like a madman. At other times he would engage in calm conversations with some of us or our cell guard. Apparently, he had been a student at a large U.S. university until he decided to drive home to eastern Canada. We were not able to learn when his psychosis began or what, if anything, may have contributed to it.

Court in Golden in those days was normally held on Saturday mornings and Wednesday evenings. Our lay judge who presided at the scheduled court was a school principal, which necessitated the unusual hours. Most of our local clients appreciated the somewhat unusual court hours because they did not have to take time away from their work to deal with relatively routine brushes with the law.

Our prisoner ranted and visited and yelled and slept and rocked the cell cage over the hours until the evening of the next day when we arranged for him to appear before the local court. The usual Wednesday evening court started at seven. I did not have a long list that evening so I asked two of the constables to very cautiously move the prisoner to court after I had dealt with the few routine matters. By arranging his court appearance that way we would not have an audience in the event our client lost control of himself, as I suspected he would. The court location was about one mile from the police building, so the prisoner had to be moved in a police car.

The magistrate and I dealt with the routine matters and had everyone out of the court building before seven thirty. The two constables brought the prisoner in and we presented him to the court. Our client became very rational and calm. He asked to have the handcuffs removed so that he could write notes. I raised an objection to this but the magistrate decided to grant his request after cautioning the prisoner that there were three relatively large police officers there who would without doubt put the cuffs on again by whatever means were necessary. The prisoner promised to behave.

The hearing began with me reading the charges and requesting the accused be remanded in custody for psychiatric assessment due to the serious nature of the charges and because he was transient. I then tried to briefly outline the circumstances of the chase and capture. I was only able to start the narrative of the event when our prisoner lost his carefully demonstrated control. In an instant he went totally wild. He screamed and kicked and fought with the three of us briefly until we were again able to cuff his hands together. We sat him on a chair and held him there while the magistrate tried, without success, to ask him a few questions about the recent happenings. Communication with the man was now impossible and the magistrate soon gave up and granted the requested adjournment in custody.

We now had our prisoner cuffed with his hands in front rather than the more effective placement behind his back. The two constables escorted him out of the courtroom and down a flight of stairs to the back door where the police car was parked just outside. Just as the three of them went through the doors I heard a scuffle, and one of the policemen yelled something about a gun. I bounded down the stairs and through the doors in time to see the prisoner kneeling on the landing with a holstered police handgun in his handcuffed hands, intent on opening the holster.

This vision was very brief because one of the constables came down across the prisoner like a football tackle. This constable weighed around two hundred and fifty pounds and had tried out for the Saskatchewan Roughriders before joining the Mounted Police. The prisoner was quite flat and the still-holstered handgun squirted out from under the two bodies. I later learned that the prisoner had lunged at one of the members as they went through the door, grabbed the holstered handgun on his belt, and heaved on it with all his weight. The swivel attachment to the waist belt gave way and the prisoner then had the holstered firearm in his hands. The safety catch on the holster slowed him just long enough to save someone from being shot.

I assisted the two constables with changing the cuff position so the prisoner’s hands were behind him, and he was soon safely into the back of the police vehicle. They drove back to the cells and I returned to the courtroom to wrap up the last paperwork of the evening. I stayed at the court for a while and then the magistrate and I stopped at a local coffee shop for a short time. I returned to the police office about eight thirty to find an ambulance there. When I went in, the prisoner was lying dead on the floor in the cellblock. The ambulance crew had been unable to revive him and had just given up their efforts.

The prisoner had once again collected his wits during the short ride from the court to the cells. He spoke civilly to the two officers and even joked about being able to grab the revolver from one of them. He ventured the opinion that there were no rules for the game they were playing and that they had clearly won that round, even though it had been close. He had a large drink of water from the fountain in the cellblock and asked if someone could get him a sandwich. He offered to pay for the sandwich with money from his effects since it was not a regular meal time.

The prisoner was returned to the horrible cage that we had for a cell. The standard cages were fabricated from sturdy steel straps about one inch wide which were riveted at every intersection to form square openings of about four inches. The frame of the cage was made from heavy angle iron; the floor was sheet steel, welded and riveted to create an almost watertight bottom. Fluid, mainly urine, would seep under the cages, which were far too heavy to be moved for cleaning. Each cage had an upper and lower bunk, again of sheet steel and angle iron. A thin, plastic-covered mattress and a blanket were provided if the prisoner did not vandalize them.

The prisoner chatted with the constables and the guard as he was again booked into the cell, not objecting to the routine search of his person and clothing. He removed his shoes and belt when requested. Before the guard left the cell room, the prisoner was lying on the bottom bunk as though he intended to go to sleep.

Twenty minutes later, when the guard looked through the small observation window in the cell room door, he could see that something was not as it should be. The guard yelled for assistance and ran to get one key to access the room and another to open the large padlock on the cage door. Another constable was in the office at the time and he attended at the cell with the guard. They found the prisoner hanging from the lattice top of the cage. He had removed his trousers and run a leg over one of the steel straps of the cage roof so that one leg of the pants hung down on each side of the strap. He then sat on the top bunk and pressed the back of his neck tightly under the point where the pant legs hung down and tied a very solid square knot under his chin. He slid his buttocks off the edge of the bunk and hung by his throat.

The guard and the constable struggled to take the prisoner down, but they were unable to raise his limp body enough to untie the tight knot in the pant legs. The constable ran to another part of the office and got a knife; however, he could not work with the knife inside the cage because he could not cut the trousers without also cutting the hanging body. There was about a ten-inch space between the top of the cage and the ceiling of the room. The constable managed to squeeze himself into that space and he began to hack at the cloth of the trousers. Finally the body was lowered to the floor and taken out of the cage. An ambulance had been called for by a radio message to a car patrolling in the town. The ambulance arrived about the time the body was cut down, but there were no indications of pulse or breathing in the body and none was restored by attempts at cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

The coroner’s inquest ruled that the death was suicide and attached no blame to anyone other than the deceased.

If this event were played out today, the final storyline would probably be: Scheideman has recently obtained employment at the local mill where the reluctant employer has agreed to hire him for a probationary period of six months. He has agreed to undergo counselling and other therapy until he is thought to be able to control his aggressive behaviour. The community is still reeling and has plunged into a campaign to eliminate all firearms, particularly those formerly used by the police.

When this incident happened in 1974, the community of Golden was very appreciative of what we had done. The local newspaper ran the story with a headline very much in support of the armed pursuit and eventual removal of the dangerous driver from the public road. My daughter, who was in grade three, was assisted by one of her teachers in making a small wooden trophy with a sports car at the top. The words “Sharp Shot Scheideman” were printed on the side of the trophy and “To Dad, Love Sherry” on the base.

I still have that trophy.