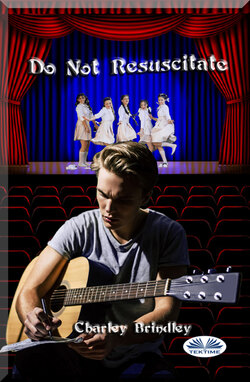

Читать книгу Do Not Resuscitate - Charley Brindley - Страница 5

Chapter Four

ОглавлениеSeptember 27, 1945

I felt a jolt, like an electric shock. But there was no pain; just a quick buzz inside my head, then tingling throughout my body. It felt as if all the blood had been sucked out of me and instantly replaced with new blood interlaced with some sort of effervescent bubbly substance. It actually felt pretty good, and my vision sharpened to crystal clarity. I closed my eyes for a moment, savoring the new feeling, then opened my eyes to see the ugly face of Justin Crammer.

“You hear me, asshole?”

“What did you say about my mom?”

“I said, your old lady can’t sew for shit.”

He glanced at Ember and his two boy pals, then grinned. He turned back and grabbed me by the collar.

I didn’t even think; just reacted. Gripping his hand, I put pressure on the back kof his wrist and twisted it to the side.

He went to his knees, crying out.

When he balled his other hand into a fist and swung at me, I twisted more, putting him on the floor.

Damn, where did that come from?

I let him go and stepped back.

I could’ve broken his wrist.

He struggled to stand but only got one knee under himself. Ember reached to take his arm, but he shook her off.

“Get away from me,” he told her, then stood. “I’ll get you for this, Brindley.”

“Okay. How’re you going to do that?”

“You’ll find out.”

“How about push-ups, right now?”

“What?”

“The one of us who does the most in five minutes, wins.”

Someone behind him laughed.

Yeah, I know, he’s the strongest player on the football team.

Crammer grinned, dropped to the floor, and positioned himself on his hands.

I handed my books to Ember and fell beside him.

We began together.

At ten, I started counting aloud.

When we hit fifteen, he slowed a little.

The other kids cheered him on.

At thirty, I said, “One-hand.”

“What?”

I put my left hand behind my back and kept going.

Crammer did the same.

He got to thirty-five, then fell on his chest, breathing hard.

I continued, pushing easily with my right arm.

“Forty,” I said, then stood and held out my hand.

He knocked it away. “This ain’t over.”

“Oh, now what?”

“You just better watch out.”

I glanced at Ember and lifted a shoulder. She did the same.

“Watch out.” She mouthed the words, then handed over my books, with a smile.

The bell rang.

Crammer stomped away, followed by Ember and his pals.

* * * * *

In history class, I took my usual seat in the back. Strange visions filled my mind, like dreaming while awake.

A war in the jungle…a wide river flowing through the rainforest…an oasis in the desert…skiing…

It was like a long movie set to super fast motion.

A smoky bar room…guitar music…me singing…

“Brindley?”

I looked up to see Mrs. Adams standing at the front of the classroom and all the students watching me, some smiling, probably expecting me to sink down in my chair and not say a word, like I always did.

“Yes, ma’am?” I said.

“I asked, who crossed the Alps to attack the Romans in two-sixteen BC?”

That’s a dumb question. Is she serious?

I just stared at her.

“That’s what I thought,” Mrs. Adams said. “Anyone?”

Several hands went up.

“Hannibal,” I said, then folded my arms.

“What?” the teacher asked.

“He took thirty-nine elephants and twenty-six thousand soldiers,” I said. “The army was divided into ten thousand cavalry and sixteen thousand foot soldiers. Probably a few hundred camp followers as well.”

“Huh?”

“Most of the elephants died in the cold in the higher elevations.” I glanced around at the other students. Ember’s mouth fell open, and the ones with their hands up, dropped them. “He also lost almost ten thousand troops.” I picked up my yellow pencil and twirled it in my fingers.

Mrs. Adams cleared her throat. “That’s the most you’ve said all semester.”

“Probably.” I opened my textbook and flipped pages, using the eraser on my pencil.

What was the name of that lake where Hannibal fought his third battle in Italy? I should know this.

I came across a picture of the Alps.

Zugspitze! The highest mountain in Bavaria.

I glanced out the window and watched an elm tree shudder in the wind.

There’s a gold-plated cross on the peak. Kabilis and I climbed up there. When? Who’s Kabilis?

“That’s not in the textbook.” Mrs. Adams came toward me, with the history textbook held against her ample breasts.

“What?”

“About the elephants dying in the cold.”

“But they did.”

“I know, but it’s not in the book.”

“Oh.”

“How did you know that?”

“I-I think I read it in the library.”

“Since when do you go to the library?”

“Um…during my lunch hour. Maybe it was in Levy or Herodotus.”

“Hmm…so you’ve read Herodotus’s Histories?”

I nodded.

“Where was Hannibal’s first battle after he crossed the Alps?”

“On the River Trebbia.”

“The second one?”

“Ticino.”

She opened her history book to where a slip of paper marked a page, then scanned down the sentences. “What was the biggest battle he fought in Italy?”

“Cannae. Fifty thousand Romans died in a single day.”

“Yes.” She looked from her book to me. “Yes, that’s true.” She turned to go back to the front of the class, but everyone still stared at me.

Bavaria. When was I in Bavaria? With Kabilis. We learned to ski that winter. He was a Tech Sergeant, U.S. Air Force. What the hell? He was fluent in German and Russian. I was a Master Sergeant. When…

The bell rang for lunchtime.

The others shuffled out. I didn’t move; couldn’t move. My head hurt from the intense pressure. So full of stuff. Jumbled. Swirling like the inside of a tornado.

“Charley.”

I jerked up my head. Mrs. Adams stood, watching me.

“Yes, ma’am?”

“Class is over.”

“Oh, okay.”

I collected my books and stood, walking in a dream. My mind was mesmerized, dazed.

What’s going on?

In the hallway, I ignored the kids, but I knew they were watching me. I went mechanically to my locker, took my lunch, and went outside, then headed to the bleachers.

There, I saw Patsy and the disabled girl. I went to their side of the stadium.

“Do you mind if I sit with you?” I asked.

They looked up at me, wide-eyed.

“Um…sure,” Patsy said.

I sat and took out my sandwich.

The two girls continued to stare, not eating or speaking.

“What kind of sandwich do you have?” I asked.

The girls looked at each other.

“Peanut butter and jelly,” Patsy said.

“Me, too,” the other one said.

“I’ve got fried egg. My mom always cuts my sandwich into two triangles. Isosceles, I think.” This was the most I’d ever said to a girl, or any kid at school.

Both girls giggled.

“Mine, too,” the other girl said.

“You want to share?” I held out half my sandwich.

“Sure.”

We traded. “What’s your name?” I asked.

“Melody.”

“Melody, like a song.”

“Yeah. My mom was a singer.”

“Really?”

She nodded and bit into the egg sandwich. “This is good.” She lifted the bread. “Your mom put mayonnaise, salt, and pepper on it.”

“You’re ‘Charley Brindley,’” Patsy said.

“Yes. Mom calls me ‘Charley Eye.’ You’re ‘Patsy McCarthy.’”

“I guess everyone knows me because I’m so fat.”

“I knew you because you’re in my science class. Do you read a lot?”

“I love to read.”

“Me, too,” I said. “This grape jelly is really sweet. I like it.”

My brain seemed to warm as it hummed. It was very pleasant, watching it fill with memories. But it was also disturbing.

Where is all this coming from? Has it been there all along and I just couldn’t find it?

“Is your mind full of memories?” I asked Melody.

“Sure,” she said. “I can remember everything back to when I was about two. Nothing before that.”

“I’m the same,” Patsy said. “I wonder why we can’t remember things from when we were babies?”

My memories seemed to be of the future, rather than the past.

Things yet to happen? How can that be?

“Do you have memories, like, from your future self?” I asked.

“I daydream a lot,” Patsy said. “About things I want to do after high school.”

“We better go,” Melody said. “It’s almost class time.”

We walked together toward the building, going slow because of Melody’s braces.

Inside the school, we were met with a chorus of ‘Pee Waldy Patsy.’

“Hey,” I whispered to the two girls, “let’s throw it back at them.”

I told them what we should do. They smiled and nodded.

“Ember and Justin, sitting in a tree,” we chanted, “K-I-S-S-I-N-G. First comes love, then comes marriage, then comes Ember with a baby carriage.”

It was a silly childhood ditty, but it had the desired effect. Several kids laughed.

Ember was stunned for a moment. “Pee Waldy…”

We sang the kissing song again and advanced on the four girls.

Ember stopped, swallowed her next words, then turned to hurry away. Her three friends followed.

“Good job,” I said to Patsy and Melody.

“That felt good,” Patsy said.

“Yes, it did,” I said. “Lunch tomorrow?”

“Heck, yeah,” they said together.

* * * * *

P.E. was the last class of the day. I hated it. I was almost six feet tall, strong, my muscles well-toned from working on the farm. But I didn’t know what to do with my strength.

Sometimes we ran the track or did side-straddle-hops; anything for exercise.

This time, we went to the gym to practice basketball.

I sat on the bleachers, still trying to sort my stampeding thoughts. I was in a war, in a jungle, but it wasn’t World War II, the one that had just ended. This was unlike anything I’d seen in the newsreels. The uniforms were different; some were just flak jackets over green tees and fatigue trousers. And the weapons. They, or we, didn’t carry heavy M-1 rifles…they were smaller, lightweight.

M-16s!

An aircraft flew over us, low, just above the jungle canopy. Very fast. It dropped napalm on an enemy position ahead of us.

That’s an Navy F-4 jet fighter plane. What the heck is happening to me?

“Brindley!” Coach Jameson shouted. “Care to join us?”

“Yes, sir.” I jumped up and ran onto the court.

The coach was a great guy. He always treated me like a regular kid, even though I was awkward and clumsy.

Coach tossed the basketball to me. I caught it and turned it in my hands.

I’ve done this before. Where? When? Vietnam…Da Nang. What the heck?

I spun the ball, then dribbled it.

Crammer came to stand in front of me. He took a defensive stance.

I watched his eyes as I bounced the ball.

He grinned, then went for the ball.

I stepped to the side. He followed my movement. I faked to the right, then went left, still dribbling. He was off-balance. I took a jump shot. The ball swished through the hoop.

Everyone stopped to stare at me.

I ran to get the ball, then dribbled it away from the hoop, turned, and made another jump shot. Perfect.

Crammer ran for the ball, dribbled it out to mid-court.

I ran for him.

He grinned and started toward the hoop.

I swatted the ball away from him, dribbled around two other players, and made a layup.

When the ball came down from the hoop, I grabbed it and passed it to another player.

Playing on a dirt court at the military camp in Vietnam. Very hot. Kabilis and I had cut our camo trousers into shorts. Six GIs on the court. Three of us had pulled off our regulation issue green tees and tossed them aside. Shirts and skins, we called the two teams.

The boy I’d passed the ball to, dribbled, took a jump shot, and missed.

I got the rebound, then threw the ball one-handed, bouncing it off the backboard. It ringed the hoop, then fell through.

The Marine commander gave us two weeks’ furlough. Kabilis and I went to Bangkok. We met…

Crammer bent his knees, raised the ball for a jump shot. Just as he released the ball, I jumped to take it out of the air, then dribbled out and made the shot he tried to make.

We played hard for thirty minutes.

The other players slowly dropped out, sitting on the floor, catching their breath.

Crammer continued to dog me, trying to get the ball.

I ran for the hoop, bouncing the ball. He tripped me from behind. I went down hard but held onto the ball.

Gunfire, mortar exploding all around us.

I stood, still holding the ball under my arm.

We were cut off in the jungle. I was a medic, working on a wounded soldier. More gunfire from the edge of the clearing, Kabilis went down, bleeding bad.

“Brindley!” Crammer said. “Come on.” He tried to swat the ball from my arm.

I passed it behind myself, to my other hand.

We fought the Viet Cong all night, losing three of our men, plus six wounded. What happened to Kabilis?

I tossed the ball to Crammer and went toward the bleachers, where I sat with my head in my hands.

“Charley.” The coach sat beside me. “You okay?”

No, something’s wrong with me.

“Yeah, I’m fine.”

“Johnson,” the coach said. “Bring that exercise pad. I think Charley better lie down for a few minutes.”

Pad? iPad! That blue doctor, in the hospital, said there was an iPad in the loft of a round barn.

The bell rang for the end of the class. The school day was over.

“You sure you’re all right?”

“I’m good, Coach.” I stood. “Don’t worry. I was just…um…thinking about my Spanish assignment.”

On the sidewalk, I waited for the bus, trying to sort out my thoughts.

So many weird things. Some guy in a hospital room, dressed in a light blue suit. He’s the one who told me about the iPad in the loft of the round barn. An iPad is a computer. What’s a computer?

Someone came to stand behind me. I glanced around; Crammer.

I hope he starts something about his place in line. This time, he’ll be the one on the ground.

“Where did you learn to play basketball?”

In the Marines, I wanted to say. Wait a minute; I was a Master Sergeant in the Air Force. How did I get in the Marines, and in Vietnam? Where the heck is Vietnam? Oh, yeah. Southeast Asia.

“Um, I’ve got four brothers. We play ball in the backyard.”

“You going out for the team?”

“I don’t know.”

I saw Patsy and Melody come out the double doors of the school building. I waved to them. They waved back, smiling.

Crammer turned that way. “Friends of yours?”His expression looked like he’d just gotten a whiff of something rotten.

“Yeah,” I said. “They are.” I walked toward the girls. “You can have my place in line,” I said over my shoulder.

“Hey,” Patsy said.

“Hi. Which bus do you girls ride?”

“Um…three,” Melody said. “But we walk home.”

“How far is it?” I asked.

“About two miles.”

“That’s a long walk.”

“Better than riding the bus,” Patsy said.

I looked toward the place where bus number three would pull up. Ember stood in line, talking to Henry Witt.

“Let me guess,” I said, “Ember and her gang like to serenade you on the bus?”

Patsy nodded.

The four school buses pulled up, and the kids began to file on.

“I’ve got to get home to start on my chores,” I said.

“Don’t forget lunch,” Melody said.

“Right. See you two in the bleachers tomorrow.”

* * * * *

I found Mom in the kitchen, working on supper. I kissed her cheek.

“How was school today?”

“Good. Very good.”

“Really?”

I nodded. “I’m going to start on chores. I have a lot of homework tonight.”

“I thought you hated homework?”

“I have some interesting assignments. History and poetry.”

She stared at me for a moment, then smiled. “Can you gather some eggs for me?”

“Sure.”

I grabbed the egg basket and headed outside. On the porch steps, I stopped to look across the backyard, past the clothesline and beyond the blacksmith shop. There stood our barn. It was huge because Dad stored a lot of hay for the winter. It was also different than most barns; it was round.

How’d that blue doctor know about our round barn? And if there really is an iPad in the loft, everything just got a lot weirder.

In the barn, I climbed the ladder.

Wow, tons of hay.

I glanced around the huge loft.

Surely, they left me a clue; otherwise, I’ll never find it.

Lots of old harnesses hung on the walls. Cobwebs everywhere.

Spiders have been at work here for decades.

An old coal oil lantern, broken doubletree, leather mule collar stuffed with straw…all covered in dust and cobwebs.

Wait a minute.

I waded through the hay to the lantern. It was perfectly clean; no dust, no spider webs.

That hasn’t been here very long. A lantern lighting the way?

I cleared the hay, down to the floorboards–and there it was: A cardboard box, just about the right size. And two more boxes.

Inside the first one, I found an iPad.

I sat back against the wall, stunned.

That guy at the hospital, he said I’d find the computer here.

So, that was a dream?

I was seventy-nine years old, dying. He knew I’d end up here, my home when I was fourteen. I’m in my body as a teenager, but I have all my memories and knowledge of seventy-nine years!

This is one hell of a hallucination, and so elaborate.

I glanced around. Every detail perfectly recreated.

I died before Caitlion got back with my Big Mac. That must be what happened. Then what is this? Afterlife? No, I don’t believe in any of that crap. I’m lying in that hospital bed, hooked up on wires and tubes. Damn it. ‘Do Not Resuscitate.’ What’s the point of signing a legal document if no one reads it? I should have had it tattooed on my forehead.

My body died, and they’re pumping life support shit through my veins. My brain is alive but hopped up on painkillers. And my mind, with no control over my dead body, has to do something.

So, I’m constructing this elaborate fantasy to entertain myself?

Two minds. Conscious and subconscious. When we sleep, the subconscious takes over, feeding dreams to the comatose conscious part. Now I’m inside the subconscious, playing this ridiculous game of reliving my high school years.

How long can it go on?

Until Caitlion gets back from McDonalds. She’ll tell them to pull the plug. She knows very well I don’t want to exist as a vegetable.

How much time do I have?

In here, in my fantasy, time may not matter. And I won’t even know when they cut my life support.

Until that happens, I’m going to enjoy this little piece of make-believe.

I opened the iPad and tapped the screen.

Uh-oh. Password.

He didn’t tell me the password.

Probably in the ‘Instructions’ folder, which I can’t get to without the password.

Down in the lower right corner of the screen was a stylized thumbprint.

Could it be?

I wiped my hand on my overalls and pressed my thumb to the icon.

Bam!

‘Hello, Charley.’

They–or I–had thought of everything.

I found the ‘Instructions’ folder and opened the file called ‘Instructions.’

Hard to miss that.

‘One. You are not immune to anything. There are very few vaccines in 1945. Measles, mumps, diphtheria, and especially polio, are all prevalent. You can probably get a small pox shot. Remember, don’t touch sick people, and wash your hands often.’

Polio, I bet that’s what Melody has.

‘Two. You can’t tell anyone about your mission. They’ll think you’re crazy, and you’ll be locked away in an insane asylum.’

Mission? What mission?

‘Three. Your mission is to prevent global warming.’

Oh, is that all?

‘When you left 2019, the world was already past the tipping point. Icecaps were melting, sea levels rising, climate warming at an accelerated rate. Two hundred years from now, the Earth will start correcting that, but the human race will be long gone.’

That’s not good.

‘You have to start the change to green energy—wind and solar.’

I’m just a kid. What can I do?

‘You’re only fourteen years old, but you have all the knowledge of mankind at your fingertips. All you have to do is design a wind turbine and solar panel.’

Yeah, right. Any teenager could do that.

‘And lastly, don’t forget to wash your hands.’

That’s it? All I have to do is stay alive and invent technology from fifty years in the future?

Polio. Wow, I forgot about that. When I was little, I saw lots of kids in leg braces. I wonder how old Dr. Salk is in 1945. He has to get to work on his polio vaccine.

I don’t want to end up in an iron lung.

I clicked on the tab for Wikipedia.

And Albert Einstein. I need to talk to him, too.

I read about obesity and polio. One link led to another. Cause and effect. History of research. Treatment and cures. Polio is caused by a virus, obesity caused by many things. Polio is highly contagious.

Before I knew it, an hour had passed.

“Charley Eye! Where are you?”

Oh, no! Mom. The eggs!

“Coming, Mom.”

“What are you doing up there?”

I clicked off the iPad, put it in the box, and covered it with hay.

“Looking for eggs.”

“The chickens can’t get up there.”

I climbed down the ladder. “Sometimes they fly up there.”

“Yeah? Let’s gather some so I can finish supper. Your dad will be home soon.”

* * * * *

During lunch in the bleachers, Patsy, Melody and I talked about the classes we shared. Melody and I had English together. All three of us were in the same history and Spanish classes. Patsy and I had science.

“Can we study history together,” I said, “after school?”

“Sure.” Melody pulled her coat collar tight against the cold wind. “It would be much easier with the three of us working together.”

“I know,” Patsy said. “I’m always running into words I don’t understand.”

“Okay,” I said. “Where?”

“Me and Patsy live next door to each other, so maybe at one of our houses?”

“That works for me,” I said.

“I’ll ask Mom if we can study at my house,” Patsy said. “But I’m pretty sure it’ll be okay.”

“Cool.” I folded my empty brown bag and shoved it into my hip pocket.

“Cool?” Melody asked.

“Yeah, fine, good, cool.”

“Okay, cool.”

“We better go,” I said. “Lunch hour is almost over.”

As we walked toward the school building, I said. “Hey, watch this.”

I ran for the flagpole, grabbed it with my left hand, swung around in the air, then gripped higher up with my right hand. I then air-walked up, moving my feet as if they were going up a wall. When I was vertical, I air-walked back down, then back-flipped to the ground.

“Wow!” Patsy said. “How’d you learn that?”

I noticed a few other kids had stopped to watch. “Um…it’s just something I learned in our backyard.”

“That was really…cool,” Melody said.

“So cool, it was almost cold,” Patsy said.

We laughed, then hurried for the doors as the bell rang.

* * * * *

The next day at lunch, I sat with Patsy and Melody in the bleachers.

“Mom said we can study at my house,” Patsy said. “She wants you and Melody to come to supper tomorrow night, then we can use the dining room to study.”

“Awesome,” I said. “How about you, Melody?”

“Yeah, I’ll be there. Can we work on Spanish, too?”

“Sure. What’s your address, Patsy?’ I asked. “I’ll tell my dad to come pick me up around nine tomorrow night. How’s that?”

She gave me her address, and I wrote it on my lunch bag.

“You want to walk home with us tomorrow?” Patsy asked.

I thought about that for a moment as I studied her address. I didn’t mind walking, but it seemed a shame since the school bus went right by her house.

“Okay.”

* * * * *

The next day after school, the three of us started down the street, walking toward Patsy’s house.

“Wait a minute,” I said.

Patsy and Melody stopped, turning toward me.

“We’re taking bus number three.”

“No,” Patsy said. “I’d rather walk.”

“If you walk home every day, Ember wins. You know that.”

“I don’t care if she wins. I hate that song.”

“We can sing, too,” I said.

Melody smiled and nodded.

“I don’t—” Patsy began.

“How about if we sing a different song?”

“What song?”

I told them what I was thinking of. We then joined the line waiting for bus number three. Ember was ahead of us, talking and laughing with her friends. She didn’t notice us.

The bus pulled up, and the kids filed on. We were the last ones.