Читать книгу Lord Sugar - Charlie Burden - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

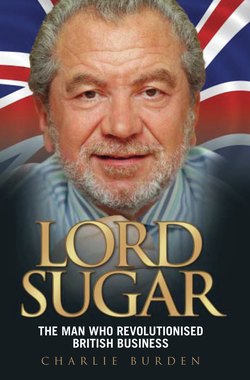

LORD SUGAR OF CLAPTON

ОглавлениеIt was an announcement that shook Westminster and much of the nation beyond. Even in the indiscreet and gossipy world of British politics, with its whispering grapevines, anonymous leaks and hushed conversations in dark corridors, there had been little indication of what was to come. The news that broke in June 2008 prompted excited, opinionated discussion: Sir Alan Sugar was to become Lord Sugar.

It was a proud moment for the boy from the East End who could scarcely have dreamed of such a moment during his humble early years in Hackney. The news was all the more surprising because of how well it had been kept under wraps. Only the same day, Sugar himself had been in a television studio giving an interview. Viewers would not have guessed what was about to be revealed later that day. He did not even hint at the sensational news. Only in retrospect was there the slightest indication when he backed Prime Minister Brown who, as usual, was receiving a raft of criticism from opponents and sectors of the media about the state of the economy.

‘I am pretty sure that if it was as dire as you are making out he would have done the right thing,’ said Sugar. ‘He is not going to step down and the reason for that is that he must have the support of the good people and of the right people.’ With that he left the studio and waited for the world to learn of his forthcoming political role.

He had been told of the appointment the previous month as he stayed at his plush holiday home in Marbella. A health-conscious man in recent years, he had taken of late to long bike rides, sometimes up to 60 miles. These epic events had given him a lean appearance that contrasted strongly with the more full-faced man who had first come to public attention during the 1980s.

He had set off on his racing bike earlier in the day and as he pumped away at the pedals, his mobile phone rang. It was no ordinary caller: Prime Minister Gordon Brown was waiting on the line for him. The PM explained that he wanted Sugar to join his administration. It was not to be possible to give him a ministerial appointment, because of his widespread business interests. However, the Prime Minister effectively delivered that famous, celebrated message: your country needs you. It was an exciting call-up for the man from Clapton. As Sugar later recalled: ‘Gordon said, “I need you to help” and we found a way – with strict guidelines – of making it work.’

Naturally, Sugar had questions about exactly how this would work and there were negotiations to be had, finer details to be agreed. Finally, after some discussion, Sugar accepted the role. It was a wonderful day for the man and his wider family. One of his grandchildren asked him what Lords do. ‘So I told him, “We represent the people. We’re there to make sure that the Government does what it is supposed to do.”’

In handing such a role to Sugar, Brown had appointed a formidable figure. Prior to announcing what name he would take as a peer, there had been discussion as to what his title would be. The Daily Telegraph’s City Diary offered humorous odds as to what name he would choose: Lord Sugar of Chigwell at 8/1, Lord Sugar of Epping Forest (Chigwell’s parliamentary constituency) 10/1, Lord Sugar of Hackney (his birth place) 16/1, Lord Sugar of Tottenham 18/1 and Lord Amstrad 33/1.

‘When the negotiations were done,’ he says, ‘it brought tears to my eyes. I thought of my mum and dad and growing up in that council house in Clapton… and I decided to call myself Lord Sugar of Clapton.’ The man from Hackney, who had been born Alan Sugar and become Sir Alan Sugar, was now going to go one better and become Lord Sugar.

The embattled Prime Minister had turned to Sugar to be his new Enterprise Tsar. What an honour. The news was announced as Gordon Brown reshuffled his cabinet. Sugar was immediately forced to defend his position, denying suggestions that his appointment was merely a publicity stunt. ‘It’s a shame it looks like that but I’m sure that… you know, I’m not the type of person to be used,’ he told the BBC’s Andrew Marr. ‘I have a passion and commitment to try and help small businesses and enterprise to see if we can get things moving again.’

He later expanded on the reasons for his new direction and his excitement at taking it. ‘It has been lacking in the past of people who really know first-hand what is needed in business. I cannot take on a ministerial role and I must not be a person making policy. All I can do is advise those that are in charge of making policy from a business point of view as to what is right and what is wrong. They need someone now in these kind of… emergency economic times that we have got… someone who has been there and worn the T-shirt on what to do as far as business is concerned. That is what interests me most in this thing. I am doing it because of the need of the country really. If you can believe me, it is not politically motivated in any way. It is more I think that small businesses and people need help.’

Who better than Sugar to offer this help? ‘With all due respect to the people in Victoria Street, they are what they are – they are civil servants and they have never actually been in business. You have got to have someone there to guide them in the right direction.’

This new position for Sugar cemented the mutual respect that he and Brown had for one another. In hard times for the economy, the man who had been Chancellor of the Exchequer for just over ten years looked to Sugar as a beacon of hope for the nation’s business and finances. In truth, this capped quite a turnabout in the relationship between Sugar and Brown.

Back in March 1992, during the previous recession under Conservative rule, Sugar had written to the Financial Times in very disparaging terms. ‘I have noted with disgust the comments of a certain Gordon Brown who has accused me of doing well out of the recession,’ he wrote angrily. ‘I do not know who Mr Gordon Brown is,’ he continued. ‘Whoever he is, he has not done his homework properly. The man doesn’t know what he’s talking about. Labour offers no sort of route out of recession.’

Hardly the words one would expect to herald a bright new relationship. However, five years later, with Labour now in power, the pair met in the flesh at a football match between Coventry City and Tottenham Hotspur. Any awkwardness over Sugar’s earlier remarks was quickly dispelled by the rapport they struck up and the ideas they discussed. It proved a meeting of minds, and more important matters than the beautiful game were on the agenda.

‘I said to him I’d be interested in embarking on visits to schools and from that moment onwards I’ve been to every single university in the land.’ Now, 12 years on from that football match chat, here he was, invited into the corridors of power by none other than Gordon Brown to help him steer the country out of recession. Presumably now Sugar felt that Brown had ‘done his homework properly’. In accepting the invitation, Sugar reprised his ‘I don’t know him’ line but directed it this time at Conservative leader David Cameron. Asked by the BBC if he would retain his position under a possible future Conservative Government under Mr Cameron, Sugar replied, ‘I have never met Mr Cameron and I don’t know anything about him.’

In truth, Sugar had been backing Brown soon after he entered 10 Downing Street as Prime Minister. It had been a tough start to Brown’s reign, with the country facing numerous trials in the opening weeks and months of his administration, including flooding, a fresh outbreak of foot-and-mouth disease and terror attacks in London and Scotland. As these horrors were taking place, there was a backdrop of rumours that members of Brown’s own cabinet were plotting against the new leader.

Sugar was appalled by this treachery. ‘You can’t run a Government and you can’t run a company or anything like that unless everybody is on side,’ he said. ‘If they are not on side [Brown] should kick them out, and then what he should do is tell the rest of the world that he has been appointed to do a job for two years and let me get on with it and then at the end of that period of time – judge me then. It’s very easy for people to blame the top man when things are no good but you have to look deeper at what these problems are.’ He was proving a fine ally to the under-fire Brown, who could scarcely have imagined the problems he would face as Prime Minister during those long years of waiting for Tony Blair to hand over the reins of power.

In backing the new Prime Minister Sugar was at pains to stress that his support was not a new affair, despite their differences all those years ago. ‘It’s not just recently that I have backed Gordon Brown,’ he insisted. ‘I’ve known him for a long time as Chancellor and I have got to know him quite well. Out of the last four prime ministers that I have had the pleasure to have met I think he is a very, very clever man and a man who is over everything and knows what is going on.’

Many have attacked Brown as lacking charisma by comparison with his predecessor Tony Blair and the opposition leader David Cameron. For Sugar this was a positive thing. ‘He may not come across as some kind of actor but he has got his hand on the pulse,’ he roared. This stance is entirely fitting: Sugar has rarely worried about the niceties of spin and chasing public approval. It is no wonder that he would be more impressed by the down-to-earth Brown than the showbusiness style of Blair.

Sugar insisted that he had no need to be positive about Brown and that he would never be blindly positive or grovel to any politician. His conviction in this regard could scarcely be stronger. ‘I have no axe to grind. Let’s face it, I have done OK – I am Sir Alan, recognised by the Queen for my services to business thanks to my natural-born entrepreneurial spirit. You haven’t seen me up the arse of the politicians. I don’t need to achieve anything or be recognised any more.’ It is certainly hard to imagine the scowling figure from The Apprentice smooth-talking his way into politics. Indeed, he did not envy Brown his job. Watching the flack that the new PM was attracting, Sugar could not help but remember the times when he’d faced criticism. It could be lonely at the top in his own fields.

‘It reminds me of my days as a football club chairman,’ said Sir Alan of Brown’s experiences. (Sugar was chairman of Tottenham Hotspur from 1991 to 2001.) ‘Walk out of the ground after giving the opponents a good hiding and the fans would shout: “Alwight, Al” … “top man” … “keep up the good work, mate” … “how’s the family?” … “well done, son”… A week later when we got our arse kicked the same group shouted: “Oi, you tosser, what you gonna do about the team then, eh?” … “get your f***ing chequebook out, you f***ing w*****”…’ Indeed, many have remarked that there are similarities between the role of the football manager and that of Prime Minister. Both jobs carry weighty responsibility in the eyes of the people of the nation who all too often believe they could do better than the incumbent.

If there was a dose of irony to his and Brown’s newfound mutual respect, it was lost on those who decided to question the appointment in more direct terms. Sugar has always been one whose mere existence seems to ruffle the feathers of some. He has often divided opinions on both sides. His entry into politics was to prove no different and soon after the announcement he was given a crash-course in the harshness of Westminster life when Baroness Prosser, who had been Labour Party treasurer in the second half of the 1990s, publicly condemned his appointment.

‘I am completely astonished that we would think that Alan Sugar is a suitable person to be a spokesman for the British Government,’ she declared. ‘He is a person who promotes via his television programme a style of management that is about bullying and sexism. If anyone thinks that’s appropriate or if anybody even thinks that’s how management works in reality then they are in a world far different from mine. I just think it is a very bad thing to have done. We’re talking about somebody whose style is completely at odds with the ethics of what I consider to be the true Labour movement.’

She was not the only Labour peer to have issues with Sugar being awarded that role. Lord Evans of Temple Guiting said: ‘He does not represent in any way anything I think about the Labour Government. For a man to be given a peerage whose public image is that of a TV bully saying “You’re fired” – well, I don’t understand how it happened. Whose decision was it? Who said, “What a jolly good idea, make him a peer”?’

That such attacks were coming from the Labour side of the fence made them particularly regrettable. Naturally, Conservative leader David Cameron took a swipe at Brown’s administration, too. Referring to the changes in the Cabinet that brought Sugar in, he said of the Prime Minister: ‘He is not reshuffling the Cabinet, the Cabinet is reshuffling him. If he cannot run the Cabinet, how can he run the country? All roads now should lead towards a General Election.’ The Daily Mail’s columnist Peter McKay joined in the criticism, writing of Brown’s moves and turning his infamous scorn against Lord Sugar by implication: ‘He thinks that associating himself with TV shows and performers endears him to voters.’

The criticism came from more considered newspaper writers too. Rachel Sylvester of the Daily Telegraph was dismissive. ‘Civil servants and business people just find the appointment embarrassing,’ wrote the political scribe. ‘The Prime Minister sees himself as Mary Poppins, giving voters a spoonful of Sugar to help the recession medicine go down – but in fact he is like a man handing out Yorkie bars which bear the slogan “not for girls”.’

Sylvester also delved into the past for support for her views, as she recalled an interview with Sugar in 2008, in which she felt he had not shown the right views and attitudes to become a part of Brown’s Government. ‘He [Sugar] also insisted that “there’s nothing wrong with being greedy”, that human rights are “rubbish” and that “this Government’s not Labour, it’s old-fashioned Tory”,’ she wrote. ‘Are these really opinions that Mr Brown wants to reward with a seat in Parliament? I would love to hear the Prime Minister’s Enterprise Tsar debating work-life balance with Harriet Harman.’

In time plenty more would have their say, both on the printed page and on the benches of Parliament. It was to prove a testing time for Lord Sugar. The Times newspaper gave over its leader page editorial on 21 July 2009 to Sugar’s appointment. ‘However, Gordon Brown has not just appointed … Lord Sugar to his administration. He has also appointed him directly to the legislature. He has done this with hardly any scrutiny, with no voting and with no debate.’ Pressing the case for confirmation hearings to take place before peerages were finalised, it continued, ‘Nothing calls more loudly for the institution of confirmation hearings than Lord Sugar’s appointment. Until such a change is made, the process for appointing outsiders to Government will remain as idiosyncratic and undemocratic as Lord Sugar’s selection of his apprentice. And it is commonly remarked that he often gets these choices wrong.’

Harsh words and a far cry from the welcome that Sugar might have hoped for, though he is no fool and will surely have expected a barrage of fire. He kept his dignity in the face of growing attacks but Sugar has always been a tough man and more than equipped to defend himself. Explaining his appointment, he said the Government had ‘been lacking people who know first-hand what is needed in business’.

Baroness Prosser’s words were drowned out by others in the Labour movement. Business Secretary Lord Mandelson was one of those who expressed a support for the appointment. He said: ‘Lord Sugar is just one heck of a man and you will see him pioneering enterprise, backing small and medium-sized enterprises around the country. That’s what we need. If we are going to succeed economically in this country, we are going to have that sort of success and Alan Sugar’s going to help us achieve it.’

Indeed, Sugar found it easy to brush off the criticisms of others, particularly from Tory leader David Cameron, a man he had form with when it came to public clashes. Sugar had won the bout each time.

In September 2008, Cameron told a journalist that he was not a fan of Sir Alan, nor his television show. ‘I hate both of them,’ he growled. ‘I can’t bear Alan Sugar. I like TV to escape.’ Sir Alan was masterfully cutting in his response. ‘I’m glad he can’t bear me,’ he said. ‘Perhaps he will stop asking people to sound me out if I want to meet him and defect to his party.’ Piling on the embarrassment for Cameron, he also accused the opposition leader of hiding from difficult questions during the harsh financial climate. ‘I am still waiting for him to answer my question: If he was in power, would things be any different?’ asked Sugar. ‘He seems to know when to stay silent.’

At the same time a BBC poll was suggesting that the public trusted Brown more than Cameron, so Sugar’s words reflected a public frustration with the Tory leader. The newspapers loved Sugar’s smart response, with one tabloid headlining its story SIR ALAN EXPOSES TORY LEADER CAM AS A SHAM. The broadsheets, too, enjoyed it, with The Times concluding: ‘With dust-ups like this, who needs reality TV?’ If the war of words between Sugar and Cameron had been an Apprentice task, it would have been the Tory leader taking the walk of shame to the taxi at the end of it. Certainly, Cameron must have wished he had never opened his mouth and his words were notably more measured when he questioned Sugar’s appointment in 2009.

There were other humorous words on Sugar’s elevation. The Sunday Times imagined Sugar at Downing Street, announcing the details of a new Apprentice-style task with Gordon Brown as the main contestant. ‘Your task today is to design a new cabinet from scratch,’ the newspaper had him saying. ‘The winners will be the team that completes the task while paying the smallest political price. A word of warning, though: in this task, there is no winner.’ When the new cabinet is completed and presented to Sugar, the paper joked, he would be distinctly unimpressed.

He asks Brown: ‘What’s that supposed to be?’ and Brown tells him it is a new ‘radical’ cabinet. ‘But it looks exactly like the old one, only worse. It’s pathetic. I gave you a chance, Gordon, and you’ve blown it. You can’t build a cabinet, your advertising on YouTube was a complete bloody joke and you’ve upset all the women in your team. I don’t want to hear any more excuses. Gordon – you’re fired.’

As we shall see throughout these pages, Lord Sugar’s Apprentice catchphrase is in danger of being worn out by those who write about him as they grope for a handy sign-off to their gags. Indeed, the man himself has pushed to have the chance to vary the phrasing he uses as he dismisses Apprentice candidates. ‘Personally, I’d have liked the flexibility to be able to vary it, to say “you’re sacked” or “get out” or possibly even “clear off”,’ he shrugs. ‘But they tell me “you’re fired” is great TV.’ It is now a phrase he will never be able to shrug off.

Increased hostility from the press was something Lord Sugar would have to become accustomed to in politics. Not that this was anything new. He remembers how, at the age of 15, he became properly aware of the political scene and the office of Prime Minister in particular. ‘It was the first time I signed on to why the country needs a leader,’ he explained. This, however, did not signify automatic respect from Sugar for the men who filled the role. Echoing his respect for leaders who eschew showbiz popularity in favour of good, sensible politics, he added: ‘In those days a Prime Minister was seen as stuffy, perhaps boring, but a serious person – a person you trusted to guide the country through the challenges it faced both at home and abroad.’ For many of the public Sugar’s preference for a reliable, old-fashioned politician ahead of a showbiz version will ring true. After spin dominated the 1990s and beyond, people want what Sugar wants and offers: sincerity ahead of celebrity.

Sugar’s first involvement in the ways of Westminster came several decades ago. He first walked the corridors of Whitehall in the 1960s, when he took a job in the civil service as a statistician at the Ministry of Education and Science. If this seems an unlikely path – full of red-tape, onerous procedures and jobsworths – for a man like Sugar to take, then that’s because it is. ‘It bores me talking about it again and again,’ he says now. He took it simply as a result of what he had and had not enjoyed during his schooling. ‘Science – this was something I had always been interested it. Statistics, maths – I wasn’t too bad at that. So I thought I’d go for it.’ He found the deskbound job to be ‘total agony’, however, and could not wait for each working day to end so he could get home. So dull was the work, he recalls, that the task of calculating what percentage of schoolchildren drank milk in the morning was one of the more exciting tasks. ‘Imagine my disappointment when I was plonked into a boring office, pushing a load of paper around,’ he remembered. He sat each day, waiting for the clock to hit 5pm.

After a year he decided to leave for good. His mother summed up the problem succinctly: her son did not like it, she said, because it was ‘a sitting-down job’. It had not been a successful introduction to the ways of politics.

Not that it was enough to put him off Westminster. Since the 1980s, he has flirted with the world of politics. This has always been essentially a two-way flirtation but it was often the case that it was the world of politics making overtures to Sugar, rather than vice versa. Sugar was more the chased than the chaser.

First, he worked for Business In The Community (BITC). Formed in 1982, BITC was launched in the wake of the Toxteth and Brixton riots which had shone such a distressing light upon the social problems blighting the lives of people in the UK’s more deprived communities. In the previous decade in America, business leaders had helped to regenerate areas such as Baltimore and Detroit. It had worked well and it was this example that BITC wanted to follow in Britain. Those quick to back the initiative included Barclays Bank, BP, British Steel, IBM, ICI, Marks & Spencer, Midland Bank and WHSmith. By 1985 there were over 108 member companies and HRH The Prince of Wales got on board as the organisation’s president.

It was alongside the Prince of Wales that one of Sugar’s first involvements took place. They travelled to Hartlepool in the north-east of England, an area with terribly high unemployment levels. There they met hordes of jobless locals, many of them young men. Sugar was transported back to his East End childhood, and through this prism saw the situation in family terms. His job was to encourage these disillusioned, desperate locals to follow his example and not the example set by his own father, who was never assured enough to launch his own business.

Looking back later, he recalled his conversations with the people of Hartlepool. ‘[I told them] they could become gardeners, window cleaners, painters and decorators,’ he said. ‘Perhaps some of them might even be able to employ one or two other people. I suggested they should have the confidence to think of starting up their own business.’

It was an inspiring message and an authentic one coming from Sugar. A man who had no silver spoon in his mouth and no inherent privilege (unlike his royal travelling companion) was showing similar people what could be done with a bit of hard work and confidence. He has since returned to the north-east to repeat the same message. In September 2009 he lent his weight to a new market being launched in Hartlepool. ‘Initiatives like this all help in increasing interest in business and encourage entrepreneurs and future entrepreneurs to achieve their goals. We need entrepreneurs now more than ever to make sure businesses survive these difficult times and are able to fully exploit the opportunities of tomorrow. I wish the organisers and stallholders in Hartlepool every success.’ With his best wishes they have a good chance.

However, back in the 1980s he was still building his own confidence to make such appearances. Slowly, his levels of self-belief rose and he felt more inclined to take on new challenges. As the decade neared its end, he was ready to broaden the scope of his public and political work. In 1988 he was invited to take on a starring role in a new Government advertising initiative. The campaign was to promote public awareness of increasing integration in the European business world. Trade barriers were coming down across the continent and the Government wanted to rejuvenate business by reminding the businessmen and women of the nation of this fact. The Trade and Industry Secretary, Lord Young, was determined to get the great and the good of British business to assist with the campaign. He approached Virgin supremo Richard Branson, ICI boss Sir John-Harvey Jones, Jaguar saviour Sir John Egan and others. Those others included Sugar, a man who Lord Young had long been a fan of.

‘He’s one of a new breed of British entrepreneurs,’ said Young of Sugar. ‘I would like to see people as role models for young people coming into business. I want people to say “Damn it, if he can do it, I can.”’ Speaking of the group of businessmen he had assembled for the advertising campaign, Young had particular praise for Sugar. ‘All of them were people who stood out above the crowd,’ he beamed. ‘There’s no question that Alan Sugar was the foremost British leader in the computer industry and electronics goods generally.’ It was this respect from Lord Young that earned Sugar the invitation. However, once he was signed up it was clear that Sugar was going to be somewhat leftfield in his approach to the project. When handed the script for his part of the television slot he was rather unimpressed by what he read. He felt it was stale and inappropriate for him.

Keen to take part in a commercial that played to his strengths, Sugar rang Young direct and told him that he wanted to re-write the script himself. Showing the sort of grasp of the television medium that would make him such a star on The Apprentice, Sugar sat down and put together a more punchy script for the commercial and one that pleased Young. Not that the Secretary had ever had serious doubts about Sugar’s ability to deliver. ‘I thought that since he knew a thing or two about marketing I wouldn’t worry,’ he said of his decision to allow Sugar to rework the script. His hunch was rewarded when Sugar sent him a script that showed a definite knack for television work. In Sugar’s version, the supremo would stand next to a set of Amstrad computers marked for despatch to different parts of Europe and explain to the camera that, under new trading rules, he would no longer have to adapt the computers for each of the different countries’ markets. He then explained what this meant for a business such as his.

This was the version that was filmed and put out by the Government. After the set of advertisements had been broadcast, research was carried out to see which of them had worked best. Sugar’s one stood proudly near the top of that chart. He had connected with the business public in a way rarely matched by the others who Young had hired to take part in the consciousness-raising exercise. Here was a sign as early as 1988 that he would have a great future in the worlds of both politics and television. The political hue of the Government might change and television was to alter dramatically over the coming decades, but Sugar would keep his place in both spheres. Indeed, he would become a key member of both worlds, famous and revered throughout his land.

In the wake of this triumph and of his BITC engagement alongside the Prince of Wales, Sugar was invited to more and more prestigious affairs, including events at 10 Downing Street and Buckingham Palace. The Hackney boy had grown into a man who was not out of place at the two most powerful, prestigious addresses in the UK. How proud he must have been as he realised that Britain’s leaders wanted to invite him to their residences. It would be 20 years before he was officially welcomed into the very highest corridors of power as Gordon Brown’s Enterprise Tsar. However, he was on his way to the top. At one of the Downing Street events he got talking with Lord Young, who noticed a trend in the way that Sugar’s working life was developing. Young observed the way the political and business sides of his colleague’s career were standing and demonstrated an accurate eye for assessing Sugar’s present and the future.

‘I suppose during the early years of the decade, up to 1986 or 1987, Sugar was riding a tiger which was almost impossible to control,’ he told author David Thomas. ‘Then, just when it’s established and he’s worth several hundred million pounds, Amstrad develops some problems. He’s got to overcome those. But by the early 1990s, the problems could be behind him and he’s got a steady business which is growing fast. It may come to the stage when it’s not a 24-hour-a-day job to run his business. Then he may look for other things to do. It may be charitable or political activities.’

Sugar was of course to become involved in both such activities. His charitable work is outlined in full in another chapter. Young felt that for the moment, Sugar’s roots made him feel at times uncomfortable as he began to dip his toe into the weird world of Westminster. ‘He’s still, I think, got a slight air of insecurity about him,’ observed Young. ‘He hasn’t shown any sign of wanting to come into the fold. That may happen later on, perhaps when he’s Sir Alan Sugar, or Lord Sugar of Chigwell, or whatever else happens in their dotage to great industrialists. Who can tell? He may not. He’s never struck me as the sort of person who sets great store on being a member of the establishment.’

What accurate and prescient words these were. Sugar has never been entirely comfortable with his place in politics, and has never desperately scrambled for a place at its top table as others have. It is this dichotomy in his relationship with political power that makes him such a suitable candidate to work within that sphere. A business supremo who showed more eagerness or even desperation to get into politics would surely be too keen and as such subject to understandable suspicion. Just as the Speaker of the House of Commons by tradition accepts the role reluctantly – when the Speaker first takes up the role, he or she is by custom literally dragged to the Speaker’s chair by colleagues – Sugar has never been one to court a political role. As Young’s words from the 1980s show, he was essentially reluctant and suspicious back then too.

Ironically, given his place at the power table of a Labour administration, Lord Sugar was a Conservative voter in the 1980s. ‘I voted for Thatcher,’ he confirmed. ‘I admired her, letting cheeky chappies like me come into a marketplace which was normally riddled with the elite. My worry about the [Conservative] opposition party now is that we’re going back to those days.’

Asked whether he would consider working with a future Conservative Government, he confirmed he would if the role offered was suitable. ‘If anybody approached me to say would I continue supporting small- and medium-sized businesses, I would say “yes”. I would continue my role under any Government,’ he said. As to whether he thought such an approach was likely, Sugar was less than convinced. He said there was as much chance of that as ‘a rabbi eating a bacon sandwich. They wouldn’t out of sheer belligerence, even if I was the best bloke in the country.’

The Conservatives were soon causing trouble in the wake of Sugar’s appointment, suggesting that he could no longer be the star of the BBC reality show The Apprentice, as his political role ruled him out of being impartial. An investigation was launched. A BBC spokesman concluded: ‘Following detailed discussions with Sir Alan Sugar, the BBC is satisfied that his new role as an enterprise champion to the Government will not compromise the BBC’s impartiality or his ability to present The Apprentice. Sir Alan is not going to be making policy for the Government, nor does he have a duty to endorse Government policy. Moreover, Sir Alan has agreed that he will suspend all public-facing activity relating to this unpaid post in the lead up to and during any shows that he is presenting on the BBC. Should he be offered a peerage Sir Alan will also be free to join other peers who do work for the BBC including Lord Lloyd Webber, Lord Bragg and Lord Winston in the House of Lords.’

However, in November 2009 there was one change to The Apprentice made in response to Lord Sugar’s political appointment. The BBC announced that rather than run the new series in the spring as normal, they would postpone it until the summer. The sixth series was due to kick-off in March 2010 but the BBC moved it to 3 June so it would be broadcast after the latest date on which the General Election could be held. This came after the BBC Trust ruled there would be an ‘increased risk to impartiality’. Lord Sugar was not happy with the decision, which he felt came after undue pressure on the BBC from the Conservative Party.

‘They’ve delayed it for some political reason, which is a bit of a joke in my opinion,’ he said. ‘Somebody from the Tory party complained to the BBC about me being an adviser to the Government and the result is that the television programme can’t be transmitted until the General Election is over.’ He was dismayed by this and pointed his famous forefinger firmly in the direction of the Conservatives in suggesting who was to blame. ‘It is very frustrating because the programme itself has got nothing in it that is political at all, but unfortunately the BBC are frightened of the Tory party. They’ve been bullied by the Tory party and they can’t stand up to common sense.’

There were inevitable changes, though, to Sugar’s life as this new political chapter dawned in his story. He was dropped as the face of the Government’s multi-million pound National Savings and Investments advertising campaign. ‘This is as per Cabinet Office rules, which prohibit the use of political figures in Government advertising,’ explained a spokesman for NS&I. Sugar added that there was no issue regarding his fee for the campaign, because he had in any case donated it to his charitable trust, of which the Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children is a major beneficiary. As we shall see in the charity chapter, Sugar’s generosity is enormous, benefiting numerous good causes.

Sugar’s popularity is also enormous, crossing generations. In 2009, British schoolchildren aged between nine and 11 were polled about who would make an ideal head teacher. Some of the results were predictable: Doctor Who star David Tennant came top of the poll, ahead of the likes of JK Rowling, Cheryl Cole and David Beckham. However, at number eight – ahead of Formula 1 driver Lewis Hamilton – came Lord Sugar. Indeed, in 2008 he had finished at the top of a poll of the British public to create a dream cabinet. Some three thousand people were asked to name who they thought would be ideal for each of the cabinet roles, from Home Secretary to Chancellor and Prime Minister. In the poll results, Terry Wogan was named Home Secretary, Gordon Ramsay made Minister for Health and Jeremy Clarkson was put in charge of transport. Stephen Fry was favourite for Deputy PM, former Countdown numbers genius Carol Vorderman was Chancellor of the Exchequer and Bono of U2 and Michael Palin would jointly run the Foreign Office. The role of Prime Minister was awarded to Sir Alan Sugar.

In real life, it was being widely suggested that Sugar’s peerage was given to him as a result of his celebrity. To students of politics, this was nothing new: Sugar was merely the latest person to become one of what the media have been calling GOATS – the acronym for the ‘Government Of All Talents’. This was not an entirely modern development. In 1914, for instance, Lord Kitchener was made war minister and later in the century media magnate Lord Beaverbrook and union boss Ernest Bevin also crossed into Westminster. More recently, Brown’s predecessor Tony Blair had given peerages to Lords Sainsbury, Simon and Adonis. Now surgeon Lord Darzi, ex CBI-director Digby Jones and Admiral Alan West all took roles in Brown’s regime. Opinion was divided in the corridors of power as to whether this tactic was a good thing. Certainly, not all hung around long, turning from ‘goats’ into ‘escape goats’. When some of the above departed swiftly, some in politics felt vindicated. ‘It’s not as easy as it looks, is it?’ they sniffed. Inevitably, some predicted that Sugar would not be a GOAT for long either.

However, Sugar’s passion and vision for politics is no flash in the-pan affair. For so long he has watched the direction that Britain is heading in and felt disapproval. Along with this, he has always held strong opinions on how to fix the nation’s problems. He has been particularly outspoken on crime, especially the striking rise in violent crime among the youth of today. ‘It’s beyond my comprehension that I hear every day of someone being stabbed,’ he says. ‘It’s like the weather. You know it’s going to happen, you just read to find out the details. It has gone bloody mad out there. It really is broken Britain. Something needs to be done and it has got to be radical. No half measures. If it were up to me I’d use a sledgehammer to crack a nut. The Government needs to invest more money in the police force. And I’m not talking about a couple of extra bobbies on the beat in each borough. I’m talking about real investment.’

Sugar entered a political world that was losing more and more of the public’s trust with each passing year. In 2008 and 2009 the scandal of expenses erupted in Westminster. With the media fanning the flames, the politicians of Britain woke up each day to the increasing anger of the public after some were exposed to have bent the rules about allowances. By the time the main body of the scandal was over, several MPs had been sacked or had resigned. The public fury turned quickly into renewed cynicism about their Members of Parliament. Sugar entered politics as the aftershock of the dark affair was still resonating. He was clear about how he would avoid getting caught up in similar trouble himself.

‘I’ve told them that I will not be taking a penny in expenses,’ he said. ‘Do you think I want to get involved in all that? Peers are entitled to a certain amount of money for every day they turn up here as well as a refund on parking, but even if I had a genuine expense I would never claim it: it’s not worth the aggravation. More importantly, I don’t need the money.’

Indeed he doesn’t, with a personal fortune estimated to be in excess of £800 million. It is not just that he does not need to bend any rules: he can also bring specialist insight to the table as a result of what he learned acquiring all that wealth. ‘I’ve made my money,’ he said. ‘I’ve employed thousands in my time and what I’m passionate about now is helping out the small businesses which make up over 50 per cent of the economy of this country. There isn’t anyone in the Government who knows as much about this as I do. When I first got involved in the football industry, it was similar to my arrival here – the elite group of chairmen made me feel like Vivian Malone Jones, the first black student to enter the University of Alabama in 1963, but I made my mark.’

His allusion to racial prejudice is a highly valid and revealing one. There is undoubtedly a strain of anti-Semitism in some of the dislike felt for Lord Sugar in some quarters in England. ‘The Jew [in England] is portrayed as Fagin, and you won’t shake that out of people’s heads,’ he once told the Israeli newspaper Ha’aretz. ‘It’s an underlying thing – that the Jews are a little bit sharp, a little bit quick, not to be trusted, possibly. If you ask a group of non-Jews in a pub what it is that they don’t like about Jews, this is what they’ll come out with… that they hoard money.’ If financial envy is at the heart of some anti-Jewish prejudice, then that envy must be felt all the more keenly towards Lord Sugar thanks to his huge financial success.

There is also, perhaps, a slice of snobbery too. For the working people of Britain Lord Sugar is, in most cases, the hero from Hackney, but for others his background is a source of distaste. It’s something he is used to: in the 1970s a trade journalist explained that Sugar’s business was ‘quite frankly rather looked down upon by the serious side of the industry… he had all the appearance and trappings of the back-street marketer.’ However, says the same commentator, within a few years perceptions of Sugar had turned around. ‘Suddenly we were aware of the fact that this back-street trader was one of the most significant people in the industry.’

Some people still believe that men from his neck of woods have no place in the upper echelons of business, much less the House of Lords. Is Sugar bothered? He could hardly be less so. Rightly proud of his background, Sugar feels it has positively shaped the way he is as a man. ‘I can’t help the way I am,’ he states firmly. Indeed, he wonders, why would he want to? ‘My East End background might have made me a little rough round the edges, but that’s not something I can do anything about. It was good training for reality; it kept me down-to-earth and taught me to quickly appraise situations and assess propositions.’

No wonder people flock to listen to his talks about business – his is an inspiring tale. ‘I fought my way out of poverty and I remain convinced that others can do likewise, too,’ he said. Not that he is disparaging of the environment in which he grew up. Indeed, he looks back at it rather romantically. ‘We lived in the council blocks and we did all the good things,’ he said. ‘You could play in the streets, playgrounds, build bikes and carts. You can’t roam around in these terrible times we live in now.’

During the 1980s an Australian journalist observed Sugar at close quarters and concluded that snobbery was definitely at work in some people’s perceptions of him. Gareth Powell, of the Sydney Morning Herald, wrote: ‘Sugar has spice, but he is not quite nice. At least this is the attitude of the computer journalists in Britain.’ After closer examination, Powell concluded that much of the criticism of him was unfair. ‘In the past few weeks,’ he wrote, ‘I have been told by journalists that Sugar is a “business thug”, whatever that may mean, and that he is never seen in public without two bodyguards.’ However, when Powell encountered Sugar at a public press conference, he said no bodyguards were to be seen and that numerous enquiries failed to produce any proof that Sugar employed bodyguards at all. Powell concluded that jealousy and snobbery were largely to blame, together with a very English suspicion of success.

Not that Sugar is romantic about his background in a naive way. Indeed, he is damning of people from Hackney who approach him believing that they automatically have a connection merely because they come from – or at least claim to come from – the same borough. ‘You can see them coming from the corner of your eye. He or she has been staring at you all night. No, not plucking up courage – these people are the worst, they are rude, they butt in, they have no common courtesy at all. They say something like, “You know my uncle in Hackney.” I say, “Oh, really?” “Yes, he says you know him very well.” Then they rattle off a name. I say, “No, I don’t know him. I’ve never heard of him.” “Oh, but you do know him.” “I don’t know him, I’m sorry.” “But you went to school with him, you must know him.” Then I get a bit annoyed. Yes, sometimes I can be rude. I would probably say, “Well, I don’t know him, so clear off” – or words to that effect.’

As he said in his maiden speech, the Lords and the public at large underestimate him at their peril. In a time of economic uncertainty and a recession which has terrified and hurt many Britons, Lord Sugar has exactly the kind of spirit which can get not just the economy going once more but also the confidence of the nation. He represents many of the key values that made Britain what it once was, and what so many wish it to become again.

Next we’ll examine each of those traits and show how Lord Sugar has them in spades, making him the man to put the Great back into Britain. From enterprise to charity, leadership to family values, via entertainment, honesty and so much more – Lord Sugar’s story will be examined via the greatest of qualities.

We’ll also assess where Lord Sugar stands in 2010 and look to his future. How will his life develop politically, in business and personally? First, though, let’s examine those qualities that he has in such abundance.