Читать книгу Staging the Amistad - Charlie Haffner - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction

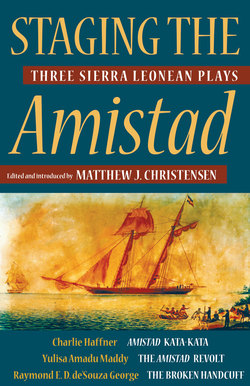

Staging the Amistad

MATTHEW J. CHRISTENSEN

Any black African artist who performs his art seriously, professionally and with sincere dedication to his people ought to use the past with the intention of opening up the future, as an invitation to action and a basis for hope. He must take part in the action and throw himself body and soul into the national struggle.

—Yulisa Amadu Maddy (paraphrasing Frantz Fanon), “His Supreme Excellency’s Guest at Bigyard”*

INCLUDED HERE in print for the first time are historical dramas about the Amistad slave revolt by three of Sierra Leone’s most influential playwrights of the latter decades of the twentieth century, Charlie Haffner, Yulisa Amadu Maddy, and Raymond E. D. de’Souza George. Prior to the initial public performance of the first of these plays, Haffner’s Amistad Kata-Kata, in 1988, the 1839 shipboard slave rebellion and the return of its victors to their homes in what is modern-day Sierra Leone had remained an unrecognized chapter in the country’s history. For the three playwrights, the events of the insurrection provided a new narrative for understanding Sierra Leone’s past and for mobilizing the nation to work collectively toward a just and prosperous future. This renewed examination of Sierra Leonean history coincided with the near collapse of the great dream of political independence from British colonization. Fueling the drive for self-rule had been the expectation of political and economic equality on the world stage. In Sierra Leone, as in so many other parts of Africa and the formerly colonized world, the persistent structural inequities of global capitalism, the cynical capture of the state by venal kleptocrats, and the post–Cold War geopolitical realignments conspired to preempt the realization of these expectations. Sierra Leoneans suffered worse than most the results. The combined effects of global inequality, political self-dealing, and debilitating economic misery found their most horrific form in a decade-long civil war that began in 1991. The conflict took tens of thousands of lives and displaced 2.6 million people.1 How Sierra Leoneans had let the dreams of freedom and equality slip from their grasp and how to reenergize them were not new topics for the country’s writers, but they took on a new and more profound urgency in this period.

To explore these questions, Haffner, Maddy, and de’Souza George could have drawn on any number of uprisings, rebellions, and insurgencies in Sierra Leone’s past, including the country’s most famous, Bai Bureh’s anticolonial war of 1898. In the events of the Amistad slave insurrection and its legal aftermath, however, the playwrights discovered especially rich material to examine historically and allegorically the discrepancy between the dreams of independence and its lived reality. The revolt took place off the Cuban coast in the early morning hours of July 2, 1839. Led by Sengbe Pieh (known also by his slave name Joseph Cinqué), fifty-three Africans broke their chains, took up a cache of cane knives, and commandeered the ship. Once liberated, the men and children, mostly Mende speakers, attempted to sail the schooner back to their home in the area of West Africa that is now southern and eastern Sierra Leone. Their initial freedom was short-lived. Unschooled in navigation, Sengbe Pieh, Grabeau, Burnah, and the other mutineers found themselves at the mercy of the Spaniards, Pedro Montes and Jose Ruiz, who sailed east by day but west and north by night, ensuring that the Amistad never strayed far from North America. In late August, the schooner was seized anew by a U.S. naval vessel and transported to New London, Connecticut, where the Amistads, as the Africans came be known, were jailed on piracy charges and made the curious objects of a legal battle over the regulation of international commerce, national sovereignty, and the natural right to liberty. By its conclusion a year and a half later, with an unlikely victory for the Amistads in the U.S. Supreme Court, the drama involved no less than the Queen of Spain and U.S. presidents Martin Van Buren and John Quincy Adams. Theirs was not, nor would ever be, a completely unqualified triumph. Upon his long-awaited return to his village, Sengbe Pieh found his family and entire village had vanished, presumably victims of the slave trade. Moreover, neither he nor the other mutineers, nor any other inhabitant of Mendeland for that matter, would ever be able to escape fully the patronizing and paternalistic oversight of white Westerners. The Christian mission set up by the white Americans accompanying the Amistad mutineers would eventually blossom and later be turned over to the British-based United Brethren of Christ Church, which, in turn, paved the path for British colonization of what was to become Sierra Leone.

Like the anticolonial discourses of earlier Sierra Leonean and African writers, Haffner, de’Souza George, and Maddy seek to reinvigorate the promise of decolonization by narrating the Amistad history in ways that privilege the values of collective endeavor, the political agency of everyday Sierra Leoneans, Sierra Leone’s power to shape world affairs, and, above all, liberty. Theirs are heroic tales of the oppressed and downtrodden asserting their rights in a world incapable of recognizing African dignity or sovereignty. The Amistad revolt proved doubly resonant in this regard because enslavement has featured more prominently in Sierra Leone’s historical consciousness of itself than in most other West African nation-states. Capital city Freetown was founded in 1787 as a haven for freed slaves from the Americas and, after the abolition of the transatlantic slave trade in 1808, the city expanded with an influx of arrivals from the entire West African coast who had been liberated from illegal slave ships by British patrols. Thus, for a country in which the meanings of liberty and equality remain shaped as much by the experience of the Atlantic-world slave economy as by the tyranny of colonization, the Amistad insurrection’s narrative of capture, enslavement, Middle Passage, liberation, and return reenergizes the common account of Sierra Leone’s origin and its status as a “province of freedom.” Yet, at the same time, the playwrights, de’Souza George especially, also find in the Amistad narrative material for questioning how Sierra Leone, with all its promise at the time of independence from British colonialism in 1961, could have found itself so quickly engulfed in such a quagmire of misery. Unlike the vast majority of the liberated African Americans and West Africans (largely Yoruba) who originally settled Freetown, the Amistad revolt’s protagonists and the slave-catchers who sold them into slavery hailed from communities that are part of modern-day Sierra Leone. The capture of the Amistad mutineers more than fifty years after Freetown’s founding thus served as a powerful reminder that just outside Freetown’s confines the Atlantic trade raged on. For as much as the plays celebrate the will to freedom emblematized by the Amistad rebels, they simultaneously highlight the pernicious social divisions and devaluation of individual life that made permissible the commodification and sale of Africans by other Africans during the era of the transatlantic trade and that were so apparent in Sierra Leone in the postindependence period when the three plays were written.

That the story of the Amistad rebellion found its home on the Sierra Leonean stage and that so many different playwrights would mine the narrative to rethink the country’s past and future is not surprising. Lacking neither dramatic conflict nor narrative suspense in its account of despotism, heroic struggle, and courtroom sparring, the history makes for good theater. In fact, in 1839, only four days after the mutineers found themselves imprisoned in New Haven jail cells and long before any reliable information about what actually occurred was available, New York City’s Bowery Theater staged a sensationalized “nautical drama” of “Piracy! Mutiny! & Murder!” titled “The Black Schooner, or the Pirate Slaver Armistad” [sic].2 To this day, the rebellion remains a seductive topic for U.S. writers, artists, and performers. Owen Davis in the 1930s and opera librettist Thulani Davis and filmmaker Steven Spielberg in the 1990s brought the mutiny to stage and screen. Poets Muriel Rukeyser, Robert Hayden, Kevin Young, and Elizabeth Alexander, novelist Barbara Chase-Riboud, and muralist Hale Woodruff have explored its themes of liberty and heroism. Even Herman Melville draws from the Amistads’ mastery of the ship and its White commanders for its narrative conflict in his novella Benito Cereno. And this is just a short sampling. Apart from Spielberg’s Amistad (1997), released nearly a decade after Charlie Haffner’s Amistad Kata-Kata premiered, few of these works would have been available in Sierra Leone and none circulated outside small circles, but a similar recognition of the rebellion’s historical and cultural import and its theatrical potential captured the country’s playwrights. Perhaps even more importantly, in Sierra Leone the stage has served as a primary site for exploring political and social questions such as those provoked by the Amistad history. This is due in part to drama’s disproportionate impact in a country with low literacy levels and a tiny population able to afford newspapers, books, or magazines. It is also a function of the country’s dynamic oral storytelling cultures and ritual performance traditions. And, as in many other former British colonies worldwide, stage drama enjoyed a privileged status as both entertainment and social critique throughout much of the twentieth century.

Stage drama was first brought to England’s colonies as a performative assertion of Britishness, and it was not uncommon to find elaborate theaters staging Elizabethan drama at the farthest-flung outposts of the empire. By the 1930s, Sierra Leoneans had begun to adapt, transform, and indigenize the theater with Krio-language translations of Shakespeare, for example, and with original scripts reflecting African realities.3 Beginning in the late 1960s, Yulisa Amadu Maddy shifted Sierra Leonean drama away from manneristic plays about Freetown’s high society to gritty realist narratives centered on the lives of petty thieves, street boys, and prostitutes who suffered firsthand the legacies of colonial racism and the hypocrisies of the social, political, and economic elite. Maddy’s plays and his position as head of the drama department at Sierra Leone Radio ushered in a new generation of playwrights, including Charlie Haffner’s and Raymond de’Souza George’s mentor, Dele Charley, dedicated to exposing corruption and the abuses of power in the young nation-state.4 If the colonial-era productions enabled white administrators and merchants to buttress their Britishness against what appeared to them as the heart of darkness (as well as, of course, to impart the so-called gift of their culture to the colonized), theater for Maddy’s generation was critical in illuminating the threats to Sierra Leone-ness while simultaneously keeping alive the nationalist ideals that fueled the drive to independence. Because they drew attention to internal as well as external threats, their work did not go unpunished. In reaction to Maddy’s play Big Berrin (1976), which takes aim at the excesses of Sierra Leone’s political elite, President Siaka Stevens jailed Maddy, added dramatic works to the country’s censorship act, and closed Freetown’s largest and most popular venue.5 These actions dampened political critique in the theater for nearly a decade, but Maddy’s generation had firmly established theater as the dominant mode of cultural production and cultural critique—more so than the novel—and as the literary form for which the country’s writers became internationally known. At the time Haffner began writing Amistad Kata-Kata, there remained, even in the face of government hostility, more than forty active drama companies in Freetown, a city with a population of only about one million.

Despite theater’s popularity, producing a play in the 1980s about an 1839 slave revolt that took place in the Americas remained neither a risk-free proposition nor an obvious choice of topic. During the worst years of the government’s clampdown on the arts, staging a play about armed insurrection was a likely ticket to jail. A few years prior to the premiere of Amistad Kata-Kata, President Siaka Stevens imprisoned a group of actors on charges of inciting violence after they attempted to stage a play about the nineteenth-century anticolonial leader Bai Bureh.6 As a brash, novice playwright with dreams of transforming Sierra Leonean society, Charlie Haffner was nevertheless savvy enough to avoid the same fate. Although Amistad Kata-Kata neither lacks veiled critiques of contemporary Sierra Leonean society nor shies away from celebrating armed insurrection against tyrannical overlords, Haffner made astute use of the new president Joseph Saidu Momoh’s 1985 campaign platform, “Constructive Nationalism,” to fashion his historical narrative as a tale of civic pride in which Sierra Leoneans take center stage in international affairs. Amistad Kata-Kata was thus all the more subversive for not proclaiming its subversiveness.7 The bigger challenge, however, might have been that the revolt history was almost entirely unknown in the country. In various interviews and presentations, Haffner has described the deep skepticism of Sierra Leonean audiences who refused to believe that common villagers could have played so prominent a role on the global stage without the revolt having already become a central chapter in the country’s historical narrative of itself.8 For Haffner, as again for Raymond de’Souza George six years later, the skepticism was symptomatic of the very problems that he sought to address in the first place and would lead him to write a play that is as much about the necessity for a robust culture of public memory as it is about the Amistad rebellion itself.

Amistad Kata-Kata

Of the three plays included here, Haffner’s Amistad Kata-Kata was the first one written and remains the only one to have been staged primarily in Sierra Leone. Born in 1953, Haffner was first introduced to the Amistad narrative as a student at Fourah Bay College, in Freetown, by the American anthropologist and historian Joseph Opala. A lively and dynamic lecturer with an unwavering belief that Sierra Leone lacked a set of shared symbols on which to build a national civic pride, Opala had started championing Sengbe Pieh as just such a symbolic figure about the same time Haffner enrolled in the college’s Institute of African Studies. Opala was not the first to recognize the leading role Sierra Leoneans played in the revolt. Sierra Leonean historian Arthur Abraham had written about Sengbe Pieh previously. But Opala was perhaps the most vociferous. Inspired by Opala’s lectures and his ideas about heroic nationalist symbols, Haffner wrote the first draft of Amistad Kata-Kata in 1986 as an assignment for Opala’s course on national consciousness. He premiered the play with the Freetong Players, the theater troupe he founded for the purpose, two years later, in 1988, at the British Council auditorium in Freetown. The Freetong Players also recorded a popular narrative ballad, “Sengbe Pieh,” included in this volume, that they and other groups performed in schools, lorry parks, markets, and just about anywhere they could find an audience. Almost single-handedly, Amistad Kata-Kata made the 1839 shipboard rebellion and Sengbe Pieh central figures in Sierra Leone’s historical imaginary.

Amistad Kata-Kata unfolds as a relatively conventional nine-scene stage drama. The play is plot driven, featuring a chronological narrative that begins with Sengbe Pieh’s capture, proceeds with the Amistads’ sale in Havana and their shipboard uprising, and concludes with the U.S. Supreme Court trial. Its one departure from the historical record comes in the form of a frame narrative set in a Mende village in the 1980s in which a university student and his grandmother discuss the imperatives of historical memory. In its frame and core narratives, Amistad Kata-Kata privileges accessibility over aesthetic complexity, favors clear dialogue over stylized language, and keeps symbolism and metaphor to a minimum. Despite the seriousness of the topic, the play does not shy away from occasional humor. Its depiction of the would-be Cuban slave owners as woebegone subjects of the victorious Amistad rebels regularly generated laughs during the performances I viewed in Freetown in 1990 and 1991, as did depictions of Sengbe Pieh flustering his white American foes by demanding to be called by his Mende name. In terms of its staging, the play requires few props and no complicated lighting, sound, or other theatrical apparatus, its modest demands reflecting the conditions of the Sierra Leonean auditoriums, public parks, school lecture halls, and other informal venues available to the country’s theater companies. While Haffner gives the play a Krio-language title that translates loosely as “Amistad Revolt,” the play itself is in English.

Thematically, Amistad Kata-Kata aims for a similar transparency, returning repeatedly to a few key points. The play depicts the rebels as never anything less than the authors of their own lives even in the moments when freedom seemed most remote; it insists that cultural self-respect is the bulwark to withstanding the crushing forces of geopolitically dominant institutions such as the transatlantic slave trade or the U.S. legal system; and it posits historical memory as a necessary foundation for civic well-being. This is not to say that Amistad Kata-Kata shies away from aesthetic or thematic nuance. In its interplay of oral and written historical practices, the play problematizes meanings of modernity, and in its employment of the multivalent trope of cannibalism, it situates the Amistad rebellion as just one, though uniquely emblematic, moment in the long history of suffering under the regimes of global capitalism.9 And, as work that above all seeks to fashion a global heroic past for the Sierra Leonean nation-state, it highlights the transnational underpinnings of postcolonial nationalism.

Amistad Kata-Kata holds its own as a literary text, but the play’s cultural importance stems significantly from its status as a work of public history. Readers and audiences should pay special attention to the figure of the grandmother who appears in the frame narrative and reappears periodically to comment on the action. In Amistad Kata-Kata’s opening framing scene, for instance, she laments the poor state of historical memory in Sierra Leone, going so far as to declare that public amnesia about resistance figures like Sengbe Pieh stands as a root cause of many of the country’s social and economic ills. Without overtly suggesting that contemporary Sierra Leoneans should follow Sengbe Pieh’s example of armed uprising, she nevertheless asserts that proper memorialization of those who resisted tyranny will go a long way toward improving the quality of life in the present. The pronouncement serves both to introduce the Amistad history to Sierra Leonean audiences and to assert Haffner’s perspective on the relationship between historical memory and collective well-being. In the same opening scene, the grandmother castigates her university-educated grandson for putting too much faith in written histories, which, according to her, are untested by the rigors of oral tradition and public debate. Like the narrative tradition lauded by the grandmother, Amistad Kata-Kata offered itself to audiences as oral history. And like the oral tradition, the Freetong Players tailored individual performances to their audiences. As a result, few performances were identical, but each amplified the same themes. In several important ways, Amistad Kata-Kata set a template for the plays to follow.

The Amistad Revolt

Yulisa Amadu Maddy (1936–2014) premiered his play, The Amistad Revolt, at the University of Iowa in April 1993. He would stage it one more time, two years later, with the title Give Us Free—The Amistad Revolt, at Morris Brown College. Based on the success of these stagings and on Maddy’s reputation as a playwright and novelist, Steven Spielberg flew Maddy to Los Angeles for discussions about developing the play into a screenplay for what would become his film. For undisclosed reasons, Maddy walked away from the negotiations, replaced by the American screenwriter David Franzoni, whose screenplay focuses the greater part of its narrative conflict on the redemption of its White American protagonists.

The Amistad Revolt stands as one of the final complete works in Maddy’s career of writing and directing for the stage. His first four plays were published by Heinemann’s African Writers Series in 1971 under the title Obasai and Other Plays. Two years later Heinemann brought out his novel No Past, No Present, No Future. Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, Maddy continued to write and stage plays, performed primarily by his drama company Gbakanda Afrikan Tiata. All of Maddy’s productions, including The Amistad Revolt, share a commitment to exposing injustice and advancing the national struggle for freedom and dignity. In addition to working in stage drama, Maddy trained and directed the Zambian National Dance Troupe for Expo ’70, in Japan, and the Sierra Leonean National Dance Troupe for FESTAC ’77, in Nigeria. During the nearly three-decade period he spent in exile following his imprisonment related to the staging of Big Berrin, Maddy also taught drama in Nigeria and the United States. In 2007, he returned to Sierra Leone, where he remained until his death in 2014.

Like Haffner’s before him and de’Souza George’s after, Maddy’s play narrates the events of the Amistad rebellion and its legal aftermath from the perspective of its Mende protagonists, depicting their uprising as a story of heroic struggle in which the enslaved maintain the unambiguous right to use violence in order to secure their liberty. And like the other two plays, the bulk of its action takes place on board the Amistad, in the Connecticut prison, and in the U.S. Supreme Court chambers. With the exception of two fictionalized African American characters, the play puts the key historical figures on stage. In his obituary for the playwright, literary critic and fellow Sierra Leonean Eustace Palmer writes that Maddy enjoyed a “profound knowledge of what the theater was capable of, what worked and what did not, and the innovations that could be made.”10 This understanding is evident in The Amistad Revolt’s complex narrative arc, its frequent time shifts—often signaled by lighting and spatial organization—and ambitious thematics, all highly demanding on the sixty or more performers who appear on stage. But while Maddy takes advantage of the disproportionately greater technological and stage resources available to him in the United States (recorded sounds, visual projections, spotlighting, and so on) than would have been available to Haffner or de’Souza George in Freetown, the script never comes across as so reliant on them that the play could not have been staged in Sierra Leone.

For all the thematic and narrative similarities to Amistad Kata-Kata, The Amistad Revolt is distinguished from the earlier stage production by its more extensive incorporation of the written record. Like Haffner and de’Souza George, Maddy quotes directly from Andrew Judson’s and John Quincy Adams’s courtroom transcripts and Kale’s letter to Adams, in which the child captive expresses so heartbreakingly his agony in face of America’s racial hypocrisies. But Maddy takes his intertextuality a significant step further. In addition to drafting dialogue from nineteenth-century legal records and personal correspondence, Maddy borrows fictionalized characters, narrative conflicts, and entire conversations and interior monologues from Barbara Chase-Riboud’s 1989 historical novel about the Amistad rebellion, Echo of Lions. The most significant of Maddy’s adaptations from the novel include the incorporation of its fictionalized characters Henry Braithwaite and his daughter Vivian Braithwaite; its attention to District Court Judge Andrew Judson’s prior involvement in the Prudence Crandall case; and its shared characterization of John Quincy Adams as being haunted by having been president of a slave-holding republic. Additionally, Maddy’s play replicates some of the novel’s narrative architecture and its linking of racial and gender inequality. So extensive are Maddy’s borrowings from Echo of Lions that his surviving family and Barbara Chase-Riboud agreed that it would be most appropriate to publish the play as an adaptation of her novel.

By no means does the play’s status as a partial adaptation of another literary text make it less compelling critically or aesthetically. Quite the opposite, in fact. Much of the The Amistad Revolt’s richness stems directly from the way that it incorporates primary source documents and fictional representations as equivalent records. At the most basic level, Maddy’s inclusion of fictional material as a historical source in its own right highlights the erasure of the slave rebel’s voice in Black Atlantic history. Apart from Kale’s letter and the brief courtroom testimony of the few Amistads chosen to speak, rarely in the court records, missionary archives, newspaper accounts, diaries, and other archival documents can Sengbe Pieh’s voice or that of any of the other rebels be found. This absence is just as true for the Amistads as for Gabriel Prosser, Denmark Vesey, Nat Turner, and the thousands of other protagonists in slave rebellions, large and small, in Africa, on board slave ships, or in the Americas. By turning to a fictional source for representations of those voices, Maddy only further highlights their profound absence in the public historical record. Like so many other authors of neo-slave narratives, Maddy also fills this vacuum, of course, with his own fictionalization of the expansive private lives of the Amistad slave rebels, imagining likely conversations, feelings of trauma, and sources of resilience, but always in transatlantic dialogue with Chase-Riboud’s “historical” source text. A second effect of giving a novel equal footing as a nineteenth-century document is to call attention to the textuality of the nineteenth-century archival materials. Those historical documents were produced by lawyers, judges, journalists, abolitionists, missionaries, and diarists who, no matter their views on slavery, were never free from the ideologies of race and civilization of their era. By giving equal credence to a twentieth-century novel by an African American writer, Maddy suggests that the available primary sources are no less fictional than a contemporary novel and that a contemporary novel can be no less factual than court records, newspaper reports, and the like. Haffner does something similar when he has the grandmother in Amistad Kata-Kata’s frame narrative question the reliability of written records. But Maddy is perhaps the more radical in turning to fiction to critique the racism of the archive and to locate voices lost to history.

The other significant difference between The Amistad Revolt and the two other plays in this volume is its deeper engagement with the psychosubjective effects of antebellum American racism on its West African protagonists. From the opening scene to the last, the mutineers’ struggle to comprehend and resist their racialization is made a central thematic focus. This is not to say that Haffner and de’Souza George ignore the effects of racism and racialization on the mutineers but rather that Maddy highlights to a much greater extent the traumas they induce. At a moment of what is perhaps his most acute despondency, Maddy’s Sengbe accuses even his supporters of viewing him as “an unwelcome nigger, to be disposed of in any way as soon as possible.” The greater focus on racism and subjectivity stems in part from the influence of Chase-Riboud’s novel. Maddy borrows the Braithwaites, her fictional African American father and daughter, using them in much the same way Chase-Riboud does to root the Amistads’ legal battle, which grew increasingly focused on esoteric questions of international trade law and executive power, in the cultures of American race relations. In the play as in the novel, the Braithwaites help Sengbe Pieh and the other Amistads understand the racial dynamics of their ordeal, naming the Amistads’ humiliations as racism and historicizing that racism as one of the foundational contradictions of American society. In return, the Amistads offer the African Americans a glimpse of a life and subjectivity untainted by the daily degradations that define Black experience in the United States. Each ultimately helps the other resist the pressures to internalize Western racial ideologies. The extensive focus on race is also very much of a piece with Maddy’s oeuvre. From his earliest plays, to his novel No Past, No Present, No Future (1973), and to his coauthored scholarly study of children’s literature, colonial racism and its internalization by Africans on the African continent and in the diaspora was central to his writing. The Amistad Revolt is especially fascinating in this respect not only because it offers one of Maddy’s most nuanced psychological portraits of the racialization of Africans displaced to England or America, but also because it represents a rare direct transatlantic dialogue between Sierra Leonean and African American writers on race, the meanings of enslavement, and resistance.

The Broken Handcuff

The final play in this collection is Reverend Raymond E. D. de’Souza George’s The Broken Handcuff. Like Haffner, de’Souza George credits Joseph Opala, his colleague at Fourah Bay College, for sparking his fascination with the 1839 revolt, and in the play’s treatment of heroic struggle and Sierra Leone’s geopolitical impact, it echoes Opala’s lectures and Haffner’s earlier rendition. And like Amistad Kata-Kata, it debuted at the British Council auditorium in Freetown. De’Souza George staged it one more time, with a reduced cast, at the 1994 Victoria Canadian fringe theater festival. It has not been performed since. The Broken Handcuff ultimately shies away from Amistad Kata-Kata’s celebratory air, cloaking the rebellion narrative instead with a bleaker, more dystopic vision. The play comes to its climatic close in the U.S. Supreme Court chambers with the announcement of the Amistads’ legal victory, but any triumph is undercut in the same scene by a slip-of-the-tongue reference to Chief Justice Roger Brooke Taney, whose Supreme Court issued the Dred Scott decision just a few years later, and by a reminder of Sengbe Pieh’s discovery upon his return to Mendeland of the likely enslavement of his entire family. De’Souza George also devotes significantly more stage time to the Mende-speaking Africans who collaborated with the coastal slave dealers, depicting them not so much as one-dimensional craven monsters than as individuals motivated by the all-too-recognizably human qualities of jealousy, grievance, and ego. And, moreover, instead of emphasizing the civic well-being to be gained by celebrating forgotten resistance heroes, The Broken Handcuff dwells more on “how much of our history and culture were swept away” because of the inability or unwillingness to acknowledge the legacies of enslavement.

A significant measure of the difference from Haffner’s play must be attributed to the changed historical context. In 1991, three years after Amistad Kata-Kata’s debut, Sierra Leone suffered the first wave of armed raids by a rebel militia calling itself the Revolutionary United Front/Sierra Leone (RUF/SL). After remaining relatively contained in the south and east of the country for a year and a half, the RUF/SL launched a major offensive in September 1992 that culminated in the capture of a large diamond-mining concession. From that point on, the already weakly equipped government forces found it increasingly difficult to check the rebel militia’s spread. In contrast to Haffner, writing only six years earlier, de’Souza George offers a narrative about the Amistad rebellion that functions much less to will into being a more civic-minded future than to question how Sierra Leone could have fallen so far from its modest prosperity at the point of political independence and let its ambitious postcolonial dreams slip away in such violent fashion.

Born in 1947, Raymond de’Souza George has played a leading role as a writer, director, actor, and mentor for young theater professionals coming up through the Institute of African Studies at Fourah Bay College, where he spent his professional career. As a founding member of the influential drama company Tabule Theater, de’Souza George acted in a leading role in Dele Charley’s Blood of a Stranger, the best original drama award winner at FESTAC ’77, the festival of black arts held in Lagos, Nigeria, which saw the staging of now-canonical plays like Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o and Ngũgĩ wa Mirii’s critique of neocolonialism I Will Marry When I Want. De’Souza George’s own scripts include the Krio-language play Bobo Lef, which was performed at the London International Theater Festival in 1983, and the English-language work On Trial for a Will, plays that take aim at the corruption of Sierra Leone’s political leaders and the failure of the country’s citizens to stop it. Like other Sierra Leonean playwrights of his generation, de’Souza George has refused to assign external figures such as Euro-American slave traders and British colonizers sole blame for the country’s ills, preferring instead to lay a portion of the responsibility in the hands of the country’s own precolonial and postindependence elite. De’Souza George does not, however, propose that Africa has met the West on equal footing. Suggesting that Euro-American slave traders would not have been able to purchase slaves if there were not Africans willing to sell their fellow Africans, de’Souza George asks, “If the West came to Sierra Leone and wanted to buy [slaves] and the Sierra Leoneans didn’t sell, who would they have bought?” At the same time, he nevertheless insists that slavery is only possible when transatlantic economic conditions are defined by a stark “difference in levels of opportunity.”11 One of the tensions giving his writing its richness stems from the challenge of representing that local culpability without losing sight of the relative socioeconomic disadvantage structuring it.

In a significant departure from Haffner’s earlier staging of the Amistad history, de’Souza George develops The Broken Handcuff’s thematics through its sophisticated aesthetic architecture as much as through plot and character. Readers and theater companies interested in staging the play thus need to pay close attention to its use of allegory and metaphor, its interplay of languages (English, Krio, and Mende), and its Brechtian theatricality. Before we are ever even introduced to the Amistad revolt protagonists, for example, part 1, scene 3 stages an allegorical encounter set in the ancestral world of the nation-state to suggest that Sierra Leone’s common historical narrative of itself has blinded its citizens to the root sources of the avariciousness and exploitation plaguing the country. As the scene begins, the lights come up to reveal a confrontation between the first colonial governor and six anticolonial nationalists from Sierra Leone’s colonial and early independence past. In their cataloguing of the physical and epistemological violence done by colonialism, the anticolonial nationalists end up unable to escape the binary relation of colonizer-colonized or to produce a useful critique of the root causes of the contemporary exploitation depicted in the play’s opening frame. At the point when the anticolonialists’ tactics appear to have reached their discursive limits, Sengbe Pieh, standing all the while in richly metaphoric shadow at the edge of the stage, steps into the light to authoritatively assert that the country’s myopic focus on its colonial history has blinded it to other equally significant genealogies, including, most obviously, the transatlantic slave trade. Similarly, in a second example, de’Souza George implicitly challenges Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o’s contention that African languages give the most authentic and uncorrupted expression to African cultures. By giving the only African-language lines in the play to the characters who have most fully embraced the Atlantic trade’s devaluation of human life—the Mende slave-catchers—the play seems to suggest that so deeply corrupted was Mende society and culture that the Mende language itself speaks the language of enslavement and alienation.

Despite his play’s bleak tone and outlook, de’Souza George never loses sight of the fact that the Amistad revolt tells the story of resistance to the seemingly overwhelming forces of exploitation in a globalized world. For as much as the Amistad rebels’ experience in his telling points to Sierra Leone’s amnesia about its exploited and self-exploitative past, the play asserts that freedom and dignity are worth fighting for and, indeed, must continuously be fought for. For all the differences that distinguish Amistad Kata-Kata, The Amistad Revolt, and The Broken Handcuff, they share this assertion. And they share the assertion that Sierra Leone, with all of its political and economic crises and with its dream of decolonization painfully deferred, is an idea absolutely worth defending. Their plays, too, serve as a reminder that Sierra Leone remained, and remains still, a work in progress, knee deep in the necessary labor of fashioning a past to define its present and energize its future. While stage drama has lost some of the dominance it enjoyed in the second half of the twentieth century, the Amistad plays’ distinct cultural labors continue to exert outsized influence over Sierra Leone’s literary production, especially in prose fiction, which has blossomed in the postwar first decades of the twenty-first century. In novels no less committed to opening up Sierra Leone’s future, Aminata Forna, Eustace Palmer, Onipede Hollist, and J. Sorie Conteh have taken up and extended the three playwrights’ attention to the country’s pasts for both the root causes of its current conflicts and the cultural, social, and historical resources required to achieve the nation’s promise. Sitting at the forefront of this literary zeitgeist, the three Amistad plays offer a powerful reminder about how literature remains a vital force in the ongoing struggle for independence and equality.

Notes on the Texts

Charlie Haffner and Raymond de’Souza George provided typescript copies of Amistad Kata-Kata and The Broken Handcuff and consulted closely for their publication in this volume. Yulisa Amadu Maddy passed away shortly before I began to assemble the plays. His personal records and manuscripts remain currently in significant disarray in Sierra Leone and England. For these reasons, the version of The Amistad Revolt that I have included here is based on a script provided by Ansa Akyea, the Ghanaian actor who played Sengbe Pieh in the University of Iowa performances in 1993. Akyea’s manuscript is extensively marked up, with passages of dialogue and song, some quite long, crossed out or added by hand. I worked with Akyea to produce a script that conforms as closely as his memory allows to the version of the play that Yulisa Amadu Maddy directed. Posthumous publication is always fraught, but I am confident that Maddy would have approved this text. I would like to note, however, that even the published script of Amistad Kata-Kata challenges accepted standards for what constitutes an authoritative text. During the height of Amistad Kata-Kata’s popularity, Haffner and his theater troupe, the Freetong Players, rarely treated the script as a fixed text. They routinely revised dialogue and adapted individual stage performances to take advantage of differential resources or to address different types of audiences. Amistad Kata-Kata was, and remains to them, a dynamic work in progress.

In my preparation of the plays for publication, I remained minimally interventionist in my editing. I corrected obvious typographical errors and made minor changes to formatting to ensure that the plays conform to general play publishing standards. Readers and actors should assume that all punctuation, language usage, and style, no matter how nonstandard, are intentional. Sierra Leonean English typically employs British spellings (e.g., honour, centre, etc.), as is reflected in Raymond de’Souza George’s script. Charlie Haffner’s play appears here with American spellings in conformity with the typescript he gave me. Maddy’s original manuscript mixed British and American spellings, with the same word occasionally spelled both ways and with no obvious organizing logic. Given that the majority of Maddy’s spellings were American and given that he wrote and only ever staged the play in the United States, his family and I chose to use American spellings throughout.

Readers of Maddy’s play should also note his differential capitalization of racial terms. In every instance, he decapitalizes the word “white” when referring to European Americans, and, with few exceptions, capitalizes “Black” and “Negro.” The differential capitalization would remain indistinguishable aurally, of course, but, visually, it ascribes with unusual force the humanity and dignity to people of African descent that the proper noun denotes and forces White readers to confront their own assumptions and privileges. Where the manuscript did not capitalize these terms, I considered the context and made a judgment about whether the decapitalization was intentional or a likely typographical error and revised accordingly. For instance, when Judge Judson spews his racist venom about race pride I chose to leave his use of the word “blacks” uncapitalized, as it appears in the manuscript, because it signifies Judson’s view of Africans and African Americans as unworthy of proper noun status. But Maddy also leaves “white” uncapitalized in the same lines of dialogue, which comes across visually as Maddy’s attempt to subvert the violence of Judson’s racist rhetoric, a rhetoric that certainly had not disappeared from American life by the 1990s.