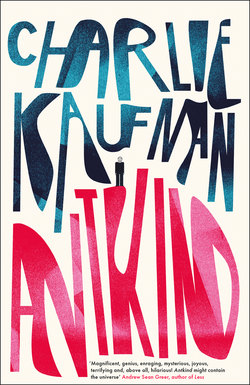

Читать книгу Antkind: A Novel - Charlie Kaufman - Страница 15

CHAPTER 9

ОглавлениеA STRANGE OBJECT, LARGE and malformed, drops from the sky behind the top-hatted man. It must be made of clay (as are humans, by the way, in so many creation myths) because it flattens upon contact with the ground. Another follows. There appears what can only be described as blackish liquid oozing from them. The horrifying hurled and sundered “bleeding balls” aside, this is a charmingly naïve undertaking. The man continues his trek across screen, and his journey causes me to reflect upon my own love of weather. The complexity of it, the power, its capricious nature. Of course weather is analogous to the finest art: invisibly moving in countless directions at once. If one watches a tree in a breeze, it becomes immediately apparent that rather than the wind blowing the tree uniformly, micro-currents move each leaf, each branch separately. The tree, leaves, and branches bounce and roll and describe circles all at once. Although Ingo’s interest appears to be in the comic potential of weather and mine in its metaphor as an engine of fate, I do feel a certain kinship with— What’s that? The top-hatted man himself is suddenly blown every which way. His tails fly up behind him, and as he attends to this immodesty, his top hat tumbles off screen right. A toy balloon blows toward the viewer, while a second toy balloon blows away from us. The man spins clockwise in place as would a child’s top, as the roller-skating boy is blown back on screen and circles the man counterclockwise. Although the animation is still naïvely executed, the concepts explored are nothing short of profound. And it is so very comical! Ha! Ha! Especially when the man plops onto his bottom and continues his spin, as if rotating on a pole inserted into his very rectum. Ha!

Soon the little boy is spinning so fast that he takes off, disappearing into the firmament. After a perfectly timed moment, one of the boy’s roller skates bops the man on the head, and after a second perfectly timed moment, so does the other. Dazed, he watches as his lost top hat blows back into frame, then, caught in a gust, lifts. We follow as it tumbles—past buildings, into the turbulent clouds made of cotton stuffing, into the ether. The camera is at first level with the hat, then above, looking down past it at the gentleman watching its ascent, then below looking up at the violent sky. Now it is amidst the clouds, which swirl past in remarkable ever-shifting configurations. The movie has gone in an eye blink from simplistic comedy to transcendent and breathtaking. The black-and-white clouds flash with lightning, the intrepid top hat now floating through a heartbreaking sea of fog. The previously tumultuous weather has settled into the ethereal, and as the hat continues its ascension, the fog thins. Soon our hat-agonist finds itself above the clouds, looking down on them. The obscured, lonely Earth far below. Now we ourselves view the world from the point of view (POV) of the hat! We tumble lazily through space, the Earth a distant stormy memory, the heavens black, punctuated by brilliant points of light. That this journey was influenced by the work of Georges Méliès is obvious, but the animation here is so far beyond anything else of that period. It is, quite frankly, far beyond anything I’ve seen to this day, with the possible exception of Wes Anderson’s The Wonderful Mr. Fox, a phantasmagoric cornucopia of treats for the eye, in every “which-way” on the screen, which reimburses the filmgoer for thon’s repeat viewings. Of course, to put Ingo’s work up against Mr. Anderson’s is prodigiously unfair, as Mr. Anderson is a highly educated aesthete and Ingo a sharecropper’s son (presumably) who worked as a Pullman porter (perhaps), but—although I must reserve judgment until I’ve viewed the entirety of this film—I do believe they will be on almost equal footing in the pantheon of this whimsically idiosyncratic and sadly obsolete art form.

The hat comes to rest on some sort of heavenly body. Clearly it is not a planet in our solar system, as the hat finds itself nested in a field of wheat-like doll arms, rustling gently in a cosmic breeze. Now the hat has become animate, although no explanation is offered. It wanders through the wheat arms, aimless, disenchanted, as we follow from above. The hat is Harry Haller, of course. How Ingo achieves this connection is a mystery. This is, after all, a top hat, but I have not a doubt in my mind that it has become Haller. It is perhaps possible that Ingo, a sharecropper’s son, has never read Steppenwolf (although he is familiar with Jung, so …), but even in that unlikely scenario, some divine force has imbued the hat with Haller’s characteristics, most notably his panoptic despair. As I watch the journey of the hat, I find myself identifying with it. I, too, am Harry Haller, you see. I, too, despair at the mindlessness around me. And so as I follow this Hatty Hatter, if you will, on its quest for meaning in a bourgeois world, I shed a tear for us all. Suddenly the terrain shifts and we (Hatter and I) find ourselves at the foot of an impossibly large mountain, reminiscent of Daumal’s Mount Analogue, which, of course, is decades away from being written. No longer aimless, Hatter begins its climb. I watch from above as it struggles toward me. I am at the peak. This is where we will meet. But who have I become in this scenario? It climbs and climbs, inching ever closer, until it sits before me, eyelessly looking up at me, and I find myself filled with love. I reach down to lift it up, my hands now made of light, and I don it. I can no longer see Hatter because it is on my head (if I look up I can see a tiny bit of the brim). Then after a moment, I remove it, the hat now glowing with its own light. I flick it as one would a Pluto Platter, and watch it spin through black space toward the faraway Earth. Again, I find myself with it as it enters the Earth’s atmosphere and gets tossed to and fro through the still-churning storm (has any time passed at all on this plane?). We finally break through the cloud cover to reveal our gentleman staring up at the sky. The glowing hat alights on his head, filling the man with newfound calm. He continues on his walk against the wind, now buoyant and chipper. Instantly, the wind rips a large branch from a tree, smacks the man in the head, crushing it like a grape, and spraying his oil-black blood everywhere. The man dies.

AND CHILDREN ARE born—the twins, whom we recognize as Momus and Oizys, but whom Ingo identifies (through an idiosyncratic sign language alphabet and key appearing screen right) as Bud and Daisy, botanical names both, which suggest “of the earth.” This reading, of course, further cemented by his choice of Mudd as their shared surname. Bud and Daisy Mudd are inseparable; they play together to the exclusion of all others. They jabber in a private, invented language (key on screen left). They are dressed in identical pinafores. This early-twentieth-century custom of dressing both little boys and little girls as little girls draws an uncomfortable parallel between infants and women (the women never outgrow these frocks, whereas the men become, by stages, by lengthening trousers, adults), but it also suggests that the boys need to “earn” their masculinity. As we now know, all fetuses begin as female. The “male” characteristics only develop later. The male “earns” his penis. At least that is what our forefathers (not to mention my own personal father, Jeremy) believed. Another and perhaps more accurate way to look at this quirk of genetics is that the male overshoots the goal of female perfection, developing past the ideal, much as the Irish elk grew a rack so large and unwieldy as to, in the end, lead to its own extinction, so the male, due to a flood of testosterone, develops a penis, that most unwelcome and unwieldy of racks (not to be confused with the so-called female rack, or bosom). Some have jokingly referred to it as a second brain, but in all humor there is, in addition to abject horror, a basis in truth. And we must wonder, as Ingo does, is the world better for these unwieldy penis “racks,” or will they, too, bring about the demise of a species?

And then, and then, and then: Daisy is accidentally but viciously murdered by Bud during a child’s game of jacks gone terribly wrong. This is the metaphoric amputation of his feminine self.

Important note:

Wolfgang Pauli?

Unus mundi?

Spin theory?

Must understand! Research!

It was, of course, an accident involving the jacks game and a bayonet brought home from the war by the twins’ father. This ragged amputation from self haunts Bud and will lead to a lifelong separation anxiety, his pairing and re-pairing (repairing!) with his future partner (a predictive title card informs us) an effort to repair his severed anima. One is put in mind of the eternal un-pairing and re-pairing of hydrogen and oxygen atoms as they un-form and re-form water, recognizing this process is analogous to the eternal un-pairing and re-pairing of Mudd and Molloy (Mudd’s future partner, a second title card informs us) writ small (writ large!).

Note:

Water splitting? Research this! Did I pack my Lachinov? Check trunk (boot) at earliest opportunity!

To further the analogy, Mudd alone is in truth two, in that Daisy is forever part of his psyche. The scars of her absence in his life, which exist as memories, provoke his every decision. Thusly, Mudd is the hydrogen (two atoms) to Molloy’s single atom of oxygen. Mudd is explosive and Molloy is corrosive. Yet together they sustain life. Surely this is what Ingo must be telling us in a title card that tells us this.

The screen goes black, horribly, darkly black. Clack, clack, clack, clack …