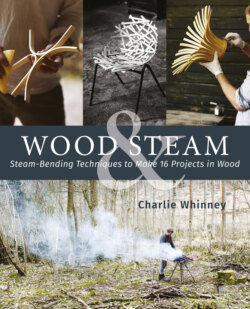

Читать книгу Wood & Steam - Charlie Whinney - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

SELECTING & STORING WOOD

ОглавлениеAll types of wood, indeed all vascular plants, are made from cells with cell walls of cellulose and lignin, and all wood no matter the species, age, and moisture content can be bent to some extent using a heat/steam process. If you are after extreme results (anything tighter than about a 1:20 thickness to radius ratio), you need to take note of the individual species, consider how dry the wood is, and look carefully at how straight the grain of the wood is. Very generally, ring-porous temperate hardwoods (broad-leafed trees from a temperate climate where you can see the growth rings easily) are normally good for steam bending, but there are plenty of exceptions. Very roughly in order of how “extreme you can go,” my top ten favorites from the woods near my workshop in Cumbria in the UK are ash, oak, elm, yew, walnut, beech, willow, birch, sycamore, and larch. If the wood is fairly low-density, such as pine, larch, and poplar, it tends to crinkle and buckle on the inside of tight bends, but gentle bends are still possible with softer timbers and softwoods. I use almost exclusively local wood, so I am not in a position to comment on every species, but I have had some really interesting and unexpectedly promising results twisting eucalyptus and free-bending softwoods. Rattan is a joy to work with – it’s impossible to break – but it shrinks along the length after bending, which took some getting used to!

I find my success rate for bends goes up if the wood is fresh or properly air-dried. If the wood has been kiln-dried or is reclaimed, I normally soak it in water first for a day or two. The worst results come when the wood has been stored incorrectly and allowed to rot or “spalt” too much; this is not always obvious until you start to bend, and then find the wood is very brittle. Tiny microorganisms have been feasting on the lignin that holds the wood together.