Читать книгу Midwestern Native Shrubs and Trees - Charlotte Adelman - Страница 15

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

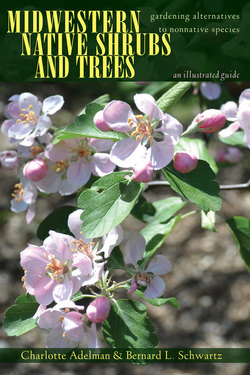

THIS BOOK ABOUT shrubs and trees is a companion to The Midwestern Native Garden: Native Alternatives to Nonnative Flowers and Plants, An Illustrated Guide. Its purpose is to serve as a useful resource for homeowners, gardeners, and landscapers seeking to evaluate prospective woody plantings. The book covers the plant qualities that the typical gardener wants to know, such as height, color, and bloom time of the nonnative plants, and their native alternatives. To incorporate a deeper level, it explores profound connections between native midwestern woody plants and the region’s ecological community. The lives of butterflies, bees, and birds are central to the discussion. The goal is to choose the trees and shrubs that make the best use of available space. The multiple objectives of visual beauty, adaptation to the local climate and soil, and maximum contribution to native wildlife can be best achieved by choosing native species for our gardens and landscapes.

Professional landscape designers call trees and shrubs the bones of the garden. “Trees are the most permanent elements in any planting plan,” notes the American Horticultural Society. “Since a tree is probably the most expensive of garden plants and usually the most prominent, selection and siting are the most important decisions. Shrubs can form the backbone of your garden design, and with their variety of foliage, flowers, fruits, and stems, they also provide interest through the seasons.”1 The natives tend to be hardier, longer-lived, and easier to maintain and grow than introductions from faraway places. When it comes to aesthetics, the native trees and shrubs growing in a midwestern backyard, garden, or landscape, regardless of their size, produce four seasons of beauty and visual impact. Midwesterners desiring an aesthetically pleasing, ever-changing tapestry of hardy plants will choose native species instead of the usual nonnative fare offered at most nurseries.

Midwestern Lepidoptera (butterflies, moths), birds, and bees evolved with midwestern plants. They need each other to complete their life cycles. Each native tree and shrub in the backyard is a life-giving force. The huge benefits to wildlife in terms of reproduction, food, and habitat that each native plant provides cannot be duplicated by nonnative species. “Planting nonnative plants, like butterfly bush, in your yard is actually making it harder for the butterflies and birds in your neighborhood to survive.”2 Though it isn’t well known, “more than 90 percent” of our native butterflies and moths can feed only on particular native host plants during their larval caterpillar stage.3 “A butterfly’s most important relationship is with the plants eaten by its caterpillars.”4 Perpetuation of a butterfly species requires a habitat that will support the full life cycle of the butterfly, not just the adult stage.5 Importantly, many native trees and shrubs excel as host plants that benefit butterfly and moth populations as well as the birds that eat the caterpillars and feed them to their offspring.

Gardeners and landscapers can choose plants on the basis of their roles in the local ecosystem. Nonnative shrubs and trees occupy spaces in our yards, gardens, and landscapes that would be better filled by native woody species that increase biodiversity. The online USDA PLANTS Database enables us to access individual plant species, determine if they are native or introduced, and check the maps. Plants shown as introduced (“I”) are defined as naturalized, not native to the area, and, in general, “likely to invade or become noxious since they lack co-evolved competitors and natural enemies to control their populations.”6 Plants shown as native (“N”) can be checked for their distribution in the United States and Canada, classification, synonyms, legal status, data sources and documentation, and related links. Reliable information takes the uncertainty out of shopping. When we choose midwestern native plants, we attract birds, butterflies, and other wildlife that add an additional layer of beauty to our yards and gardens.

Whether used as a sanctuary, a miniature nature preserve, or a playground for children, yards, landscapes, and gardens of native plants are a sound investment and provide peace of mind. Midwestern native plants have been here since the last Ice Age. For more than 10,000 years, these plants adapted to the region’s soils, seasons, rainfall, and wildlife. Native woody and herbaceous plants are beautiful and hardy, and once established they require less maintenance than conventional lawns and nonnative ornamentals. Because native plants have adapted to local conditions, they are more resistant to pest problems. Synthetic pesticides, herbicides, and fertilizers have no place in the native garden, as they kill butterflies, other pollinators, and the plants themselves and harm human health. (If problems arise, we can employ other ways to control them.) Natives rarely need watering. They improve water quality and reduce flooding, serve as carbon sinks, and reduce the demand for nonrenewable resources. The US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) explains that “native landscaping practices can help improve air quality on a local, regional and global level. Locally, smog (ground level ozone) and air toxics can be drastically reduced by the virtual elimination of the need for lawn maintenance equipment (lawn mowers, weed edgers, leaf blowers, etc.) which is fueled by gasoline, electricity or batteries. All of these fuel types are associated with the emissions of [many] air pollutants.”7 Reduced lawn and expanded native plantings produce healthier environments, and the absence of loud machinery brings peace and quiet. Regionally native plants create an authentic sense of place in the landscaping at home, in parks, and in other public places throughout our communities. While creating a future for the regional ecosystem, native gardens with diverse plants that attract a host of birds, butterflies, and beneficial insects also serve as convenient places to learn about plants and wildlife and simply enjoy nature.

There are other benefits. Gardens of native plants reduce opportunities for nonnative plants to overrun the landscape. Seed from native plants that is carried by wind and birds from our garden into natural areas does not degrade the environment. “Nonnative plant species pose a significant threat to the natural ecosystems of the United States. Many of these invasive plants are escapees from gardens and landscapes where they were originally planted. Purchased at local nurseries, wholesale suppliers and elsewhere, these plants have the potential of taking over large areas, affecting native plants and animals and negatively changing the ecosystem.”8

The statistics are alarming. In the United States, more than 100 million acres of land have been taken over by invasive plants and the annual increase has been estimated to be 14 percent.9 “The impact of all of these nonnative plants is creating novel ecosystems that are not supporting food webs, therefore not supporting biodiversity.”10 The huge numbers of nonnative plant species that have naturalized and flourish without human assistance can be seen by looking at the maps on the USDA PLANTS Database. Native plants once grew in the spaces now holding naturalized nonnative plants, and their absence deprives birds and butterflies of reproduction sites, shelter, and food. History also shows that many seemingly benign nonnative plants become invasive. Eliminating this possibility from our own gardens and landscapes is a significant advantage of going native.

Research of interest from an ecological perspective also serves to scientifically document the potential negative impacts an invasive plant can have on human health. Studies reveal that the exotic invasive shrub Japanese barberry provides habitat favorable to the blacklegged tick, exposing people to tick bites and the associated Lyme disease threat.11 Another study looked at how leaf litter in water influences the abundance of mosquitoes, which can transmit West Nile virus to humans and wildlife, and found that two of the most widespread nonnative, invasive plants, Amur honeysuckle and autumn olive, yielded significantly higher numbers of adult mosquitoes than the other leaf species. Nonnative invasive plants “are having very significant ecological impacts, displacing a lot of native species. And now we’re seeing that some of them also enhance the transmission of a dangerous disease,” said the researchers.12 Choosing native species is the ounce of prevention that is worth a pound of cure.

A plant’s origin is the key to its beneficial ecological role. Is the tree or shrub native to the Midwest, or an introduction from Eurasia? Is the plant a true native, or is it a nativar (a recent term combining the words “native” and “cultivar”)? People making gardening and landscaping decisions may feel too busy or distracted by other concerns to pay attention to the origins of their woody plants. This book aims to lighten that burden by providing this information. Awareness of the key environmental role played by native plants encourages landscaping that benefits birds and butterflies rather than a nursery’s preferences or the landscaper’s convenience. A plant’s origin is relevant when the town or city where you live conducts an annual tree sale for its parkways, or a local organization sells plants to raise revenue for a good cause.

It seems counterintuitive, but the majority of plants used in agriculture, forestry, and horticulture in North America are not native to the continent.13 One of the biggest—yet least recognized—impacts humans are having on urban habitats is a change in vegetation from predominantly native to nonnative species. “As the nursery industry evolved in the 1800s, exotic plants were imported from foreign lands. As a result, approximately 80 percent of the plants in the nursery trade today are non-native exotics.”14 And, about 80 percent of suburbia is landscaped with plants from Asia.15 The majority of woody plants in the United States that became invasive were introduced into this country for horticultural purposes.16

Studies indicate that a plant that is invasive in one region might be problematic in another region, particularly if the two regions have similar climates. For woody ornamental species, for example, being invasive elsewhere was the single best predictor of potential invasiveness in a new region of introduction.17 Unfortunately, there is no screening method to determine if newly introduced plants are going to become invasive. Estimates have put the economic cost of invasive plants in natural areas, agriculture, and gardens at $125 billion per year, and deem it to be “rising quickly.”18 Laws to prevent the sale of invasive plants are created only after the plants have already become a problem. Even then, outlawing nonnative invasive ornamental species is sometimes opposed because their sale is economically beneficial to the nursery industry and to the state.19

Decades can pass before a seemingly inoffensive nonnative ornamental plant becomes invasive. “In general, introduced plants [defined as not native to the area that have naturalized] are likely to invade or become noxious since they lack co-evolved competitors and natural enemies to control their populations,” states USDA PLANTS.20 The marketing period—the number of years nonnative horticultural plants are sold—has profound influence on their naturalization and invasion. As long as they are sold, nonnative plants will continue to naturalize and invade, notes a federal study.21 This pattern also applies to cultivars of nonnative plants.22 Even “sterile” nonnative invasive cultivars, though less fecund, eventually produce enough pollen and seed to reproduce, so cultivars of invasive plants remain invasive and are not “safe” for the environment.23

Plant choices, like clothing styles, have gone in and out of fashion. Plantings reveal information about the landscaping time period of a home or neighborhood, but there is usually a common denominator in the plants’ origins—Europe or Asia. Studies verify our personal observations. “Most of the ornamental species in parks and gardens are alien, e.g., lawn grasses, rose bushes, lilacs.” Introduced flora dominates “the visual impact of the flora in much of middle North America.”24 The persistence of consumers’ habits in choosing introduced species is revealed in popular garden catalogs that continue to advertise nonnative ornamental plants.25

Creating environmental benefits that never go out of fashion is a byproduct of choosing native species. Arguing that “for the first time in its history, gardening has taken on a role that transcends the needs of the gardener,” Douglas Tallamy, author, researcher, and professor and chair of the department of entomology and wildlife ecology at the University of Delaware, writes that gardeners have become “important players in the management of our nation’s wildlife.” “Gardening with natives is no longer just a peripheral option” but one that “mainstream gardeners can no longer afford to ignore.” “It is now within the power of individual gardeners to do something that we all dream of doing: to make a difference. In this case, the ‘difference’ will be to the future of biodiversity, to the native plants and animals of North America and the ecosystems that sustain them. . . . My argument for using native plant species moves beyond debatable values and ethics into the world of scientific fact,” he writes.26 “As quickly as possible, we need to triple the number of native trees in our lawns and underplant them with the understory and shrub layers absent from most managed landscapes.”27

The prospect of planting native species is ethically, morally, aesthetically, and scientifically appealing. But the fear that plantings of native species look messy, weedy, disorganized, or unplanned can be a deterrent. These fears, though understandable, are misplaced. “There is no inherent conflict between creating a beautiful garden and establishing a functioning, sustainable garden ecosystem.”28 Whether the plant is native or introduced from Eurasia makes no difference to its appearance (though many introductions and cultivars are high maintenance). Many native species resemble or look exactly like popular nonnative species and share cultivation requirements. A plant’s origin does not determine its ornamental role. “Basic design concepts using natives are exactly the same as those used when landscaping with aliens. Small plants in front, tall ones in back, and so on,” writes Douglas Tallamy. “Along with a beautiful garden,” we are trying “to create new habitat for our animal friends,” so “native border gardens should be as wide as possible and as densely planted as possible.”29 The factors that will determine a purposeful and neat-looking planting are selecting plants that fit the site, the garden and landscape design, the style and layout, and maintenance. When we choose native species that fulfill our aesthetic requirements, select the best locations for their well-being and our sensibilities, and provide them with maintenance that ensures their health and the desired well-groomed appearance, we take meaningful steps to reverse the region’s declines in birds, bees, and butterflies. Plantings and gardens of native species are eternally fashionable.

Birds and butterflies are a big reason for gardening. These beautiful creatures bring a lot of pleasure to adults and children. Birds and butterflies are naturally more attracted to native plants than to most exotic plants, because over thousands of years our local insects and birds have evolved to depend on indigenous plants for their food, reproduction, and shelter.30 Eurasian plants evolved in faraway places where they developed cycles of bloom times that can be too early or too late to provide midwestern pollinators with pollen and nectar, and cycles of fruit production that don’t meet the needs of native birds. “Native plants, which have co-evolved with native wild birds, are more likely to provide a mix of foods—just the right size, and with just the right kind of nutrition—and just when the birds need them.”31 To survive freezing nights, small songbirds like black-capped chickadees must sustain themselves with berries rich in fats and antioxidants. Yards and gardens with abundant native shrubs and trees enable birds to spend less energy foraging.32 Some migrating warblers time their spring return to the Midwest to coincide with the emergence of little-noticed and beneficial insects that, in turn, time their emergence to coincide with the new growth of native oak leaves.33 When required native host plants are too hard to find or unavailable, Lepidoptera will not reproduce. When native plants are readily available, more species, greater numbers, and healthier butterfly and moth populations occur. Reproduction rates corroborate this. On average, native plants support 13 times more caterpillars (larval stage of butterflies/moths) than nonnative plants.34 “Adaptation by our native insect fauna to plant species that evolved elsewhere is a slow process indeed.”35 To enjoy birds and butterflies within our lifetimes, we must plant natives.

For nesting birds, the importance of native woody plants cannot be overstated. Birds nesting in nonnatives such as buckthorn and honeysuckle are more likely to fall victim to predators such as cats and raccoons. This is due to characteristics like sturdier lower branches.36 Bird reproduction is controlled by food availability. Contrary to what many people believe, most “birds do not reproduce on berries and seeds,” Tallamy says, noting, “Ninety-six percent of terrestrial birds rear their young on insects.” For insects, including butterflies, to exist, they must lay their eggs on “host plants.” Butterfly caterpillars don’t eat most nonnative plants, which they find toxic, bad tasting, or tough, so butterflies rarely lay their eggs on them.37 Most butterfly caterpillars eat native host plants, and that is where the birds go to find them. “If you have a lot of trees that are not native, to the birds, it’s almost as if there are no trees at all.”38 Planting natives makes life easier for nesting birds to feed their nestlings. Comparisons done of production of the butterfly and moth caterpillar stage eaten by insectivorous birds demonstrate that Asian woody species produce a significant loss in breeding bird species and abundance.39 Don’t worry about birds eating all the caterpillars. When we create a diversity and abundance of native host plants, the resulting populations of caterpillars are more than adequate to sustain healthy populations of both butterflies and birds.

We associate hummingbirds with flower nectar, but they feed insects to their rapidly growing young, and the adult birds eat them too.40 Sunflower seeds entice cardinals to bird feeders, but they eat and feed insects to their nestlings.41 Chickadees, another popular visitor, almost exclusively feed their babies Lepidoptera caterpillars.42 “Regardless of the size of your yard, you can help reverse the loss of bird habitat. By planting the native plants upon which our birds depend, you’ll be rewarded with a bounty of birds and natural beauty just beyond your doorstep.”43 “Studies have shown that even modest increases in the native plant cover on suburban properties raise the number and species of breeding birds, including birds of conservation concern. As gardeners and stewards of our land, we have never been so empowered to help save biodiversity from extinction, and the need to do so has never been so great. All we need to do is plant native plants!”44 (For information on caterpillar productiveness of some important woody and herbaceous species see Selected Bibliography and Resources for Native Woody Species and Native Herbaceous Species in Descending Order of Lepidoptera Productivity.)

Modern landscapes are heavily loaded with male-only trees and shrubs, favored by landscapers because they are “litter-free.” Because male plants don’t produce fruits or seeds, they have long been considered to be desirable landscape plants. For allergy and hay fever sufferers, there is an unintended and unpleasant consequence. The very abundant, lightweight pollen produced by many male conifers and broadleaved trees is intended to pollinate the flowers of their female counterparts, but a lot is blown by the wind into people’s noses. “In contrast, a flower, tree or shrub pollinated solely by insects can be ruled out as an important cause of hay fever.”45 To prevent unneeded suffering, here is a tip. Don’t purposely plant male (pollen-producing) plants. Commonsense landscaping includes a good mix of naturally sexed native shrubs and trees. It also benefits wildlife because the buds, fruits, nuts, and seeds found on female trees are their food.

“As people learn the importance of native plants, they begin shopping for them. However, straight species are hard to find. Nearly every plant currently available is a cultivar of a native.”46 “‘Nativar’ is one term for a cultivar of a native species,” states the Wild Ones website. “Like all cultivars, nativars are the result of artificial selections made by humans from the natural variation found in species. Nativars are almost always propagated vegetatively to preserve their selected trait, which means they no longer participate in natural reproduction patterns that would maintain genetic diversity.”47 Traits they are bred or selected for include showiness, compactness, or resistance to a specific problem—but not all problems—as gardeners know who complain about poor performance.

Gardening with nativars is a risky experiment. Studies are under way, but the science is still in its infancy.48 “The biggest danger is that the nativar may interbreed with a local genotype, destroying and replacing the local genotype,” warns naturalist Sue Sweeney. “Interbreeding might turn a local genotype into a plant that the local fauna can not recognize as food, or, worse yet, into an invasive.”49 How nativars meet wildlife’s fundamental needs is an important subject that has not been widely explored. Some shortcomings are apparent. When scientific breeding changes leaf color (green leaf becoming purple or variegated), the leaf chemistry is undoubtedly changed. Variegated leaves in cultivars have less chlorophyll than solid green leaves and so are less nutritious for insects. Purple leaves are loaded with chemicals that deter insect feeding.50 A result is less insect food for nesting birds. An example is ninebark (see Spring Shrubs, p. 44). Selecting for height produces more lost food for birds. An example is ‘Gro-Low’ Fragrant Sumac (see Fall Shrubs, p. 242). Advertised for ornamental fruit, not all serviceberry nativars produce (see Spring Trees, Serviceberry Cultivar/Nativar Note, p. 78). At this time, only female inkberry nativars are commercially available.51 The female shrubs need a male to produce fruit, so birds go hungry. Sterile nativars are “bad news for goldfinches, who want the seed,” and doubled flowers are “bad news for pollinators, who can’t effectively reach the pollen and nectar.”52 An insect’s mouthparts can only pollinate plants with “a particular morphology” [form and structure of an organism or any of its parts], so “altering a flower’s shape might make it incompatible with pollinators.”53

Nursery industry marketing strategies call for frequently offering new, trendy nativars featuring different colors and shapes. What can a consumer do when nearly every plant currently available is a nativar?54 Patronizing native plant landscapers, nurseries, and plant sales, and being selective when visiting generalist purveyors, are ways to overcome these challenges. Midwesterners can create gardens, yards, and communities composed of true native plants.

The idea of restoring all of North America’s ecosystems to a pure, pre–European immigrant state is unrealistic. But perfection is not required. Recognition of the fundamental connection between native plant species and wildlife is essential. This insight leads to pitching in and planting native species in areas over which we have unique control (yards, gardens, condominium balconies). Choosing natives is a practical, direct, and enjoyable way to help wildlife and achieve immense good. To our readers we say, before planting a shrub or tree, think about the beauty and the environmental benefits provided by our true native midwestern woody species.

Each gardener and landscaper should decide on the pace at which to convert to native shrubs and trees. Substituting natives for nonnative species need not require a drastic overhaul of a garden. Homeowners may choose to proceed gradually, adding or replacing nonnative shrubs and trees as they decline or die. Some may opt to do it themselves, others to employ a professional native plant landscaper, or some combination of these approaches. Going at one’s own pace is essential to achieve the most joyful and ultimately successful results. Before you start planting and rearranging, consider the essential items (cover, food, water, reproduction) for birds and butterflies, and plan so that you use the space you have in the most effective manner. To maximize space, create layers of taller trees, shorter trees/shrubs, and herbaceous plants. While you are planning your yard, remember to plan places for yourself. Place birdbaths and wildlife-attracting native plants within window view. Keep bird, butterfly, caterpillar, and plant identification guides at the ready. Put a bench in a quiet place and enjoy.

We’ve examined a range of well-documented reasons that inspire midwestern gardeners to choose true native shrubs and trees. Regardless of the concepts that resonate most with you, we offer some great choices. For the best results, take your time. Go beyond our suggestions. Develop your own ideas based on observation and your own research. Enjoy the aesthetic—and bird and butterfly results—with friends and neighbors. Share the seedlings, root sprouts, seeds, nuts, and acorns that can grow into treasured trees and shrubs. Include native flowers, grasses, and sedges in your yard or garden and create an even more varied, beautiful, and welcoming natural habitat. Collect native plant nursery catalogs and spend time marveling at images of beautiful native trees and shrubs. Ask your local nursery or garden center to stock true native species.

For yards, gardens, and landscapes, large and small, our book can serve as a handy guide for choosing true native midwestern shrubs and trees.

Purveyor Note

Locating purveyors of native plants can seem challenging, but native plants can be obtained from a variety of sources. (Please see Selected Resources in the bibliography.) Check local newspapers for native plant sales held by park districts, forest preserves, municipalities, local environmental and native plant organizations, and individuals seeking to share the bounty produced by their beautiful native gardens. Ask these entities to suggest nurseries, retailers, wholesalers, and landscaping services that specialize in native plants. For a wide variety of native midwestern species, access online native plant sellers. Obtain catalogs to peruse at leisure; they are informative and sometimes suggest garden layouts. Their large inventories, the ease of ordering, and the convenience of deliveries right to one’s door are attractive features. If a local retail nursery, “big box” garden center, or all-purpose online plant seller offers some native selections, be sure the listing or the label substantiates that the plants are true native species. “In scientific names, cultivars are mentioned within single quotes, as in Juniperus virginiana ‘Taylor’ for Eastern redcedar. But in commercial names (common and scientific), quotes are sometimes missing.”55 Even without quotes, names like Taylor put one on notice. Purchasing true native plants will become easier as customers let sellers know they want the true or straight midwestern native species.

Environmental Reminder

Removing native plants from their natural environments increases their vulnerability. Removal also decreases survival chances for the beneficial insects, including butterflies and specialist bees that depend on the native plants for survival. We urge you to patronize purveyors of native plants, shrubs, and trees (see the Selected Resources section in the bibliography) and to share native plant bounty among friends, relatives, and neighbors.