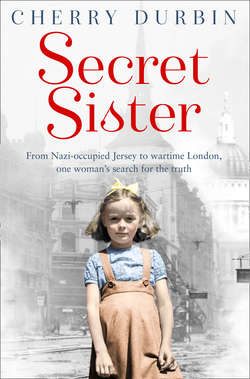

Читать книгу Secret Sister: From Nazi-occupied Jersey to wartime London, one woman’s search for the truth - Cherry Durbin - Страница 7

1 Mum Looks Like a Chinaman

ОглавлениеI was a war baby, who used to scream when woken by the wail of the air-raid sirens and the middle-of-the-night dash for cover. Dad told me that he and Mum normally huddled under the stairs until the all-clear sounded, but one night, for some reason, he decided that we should all go to the neighbourhood shelter – and it was just as well he did because that night our house took a direct hit and the stairwell was destroyed. The top of the shelter we were in collapsed and rubble showered down on us, but no one inside was hurt. If it hadn’t been for Dad’s last-minute decision my story, which began with my birth in March 1943, would have been a brief one.

We’d been living in Hayes, Middlesex, but after the bombing the Red Cross billeted us with a family in Uxbridge, next to the railway line. We had the back scullery and front bedroom, and my earliest memory is of standing up in a makeshift cot, looking out the window at the lights of the trains trundling past. It must have been tough for my parents; they’d salvaged any possessions they could from the wreck of our house, but like many other families at the time they’d lost most of their furniture, kitchenware, clothes and prized personal possessions. Dad retrieved all the scrap wood he could to make new furniture, but many things simply couldn’t be replaced. Meanwhile, Mum had me to take care of. She said I was a greedy baby and she struggled to get extra rations of national dried milk to feed me; I also scratched incessantly if there was wool next to my skin, but it didn’t prove easy to find substitute fabrics for vests in wartime.

The war influenced us all in another way as well: I was only being brought up by my mum and dad, Dorothy and Ernest Vousden, because the woman who had given birth to me was unable to look after me. Mum said that the first time they went to see me I was in a grubby little cot wearing a dirty nightie. She and Dad couldn’t have any children of their own and desperately wanted me, so they took me to live with them when I was just a few weeks old then adopted me in a court of law. This was explained right from the start, and it never bothered me in the slightest. On the contrary, I felt lucky because I had two wonderful loving parents who doted on me.

‘Where is my real mum, then?’ I asked Dad sometimes, and he always replied, ‘In the land where the tigers grow.’ That sounded reasonable to me.

We moved to Salisbury, Wiltshire, which is where I started school at Devizes Road Primary. Dad got a good job as the representative of a leading aviation company, Fairey Aviation, at RAF Boscombe Down, where top-secret experimental aircraft were tested, and Mum was a stay-at-home mother who cooked wonderful meals, baked cakes, knitted, sewed, crocheted and generally took the best of care of us. She made most of my clothes by hand and taught me how to knit and crochet myself. Once a week she washed my hair in rainwater to make it shine, and used a product called Curly Top in a futile attempt to give me curls. Her own hair was worn in what was known as a ‘victory roll’, sweeping off the forehead into two lavish loops on top. She was a statuesque lady who always dressed smartly, in hat and gloves, when we went out somewhere, and she made sure I looked spick and span as well.

Mum was very musical and she’d be singing as she sharpened the knives on our back doorstep, scrubbed the sheets on Monday wash day, or sewed new outfits for me on her Singer sewing machine. She taught me all the old wartime music-hall songs: ‘The White Cliffs of Dover’, ‘Roll Out the Barrel’, ‘My Old Man Said Follow the Van’ and ‘My Bonnie Lies Over the Ocean’. She played the piano beautifully, and at bedtime, after Dad had read me a story, Mum would play a song on the piano to lull me to sleep. My favourite was one called ‘Rendezvous’. I loved to drift off with the sound of the piano floating up from downstairs.

From my earliest years, I simply loved animals. We had a Corgi called Bunty and a cat called Dinky, who stood in as my playmates since I didn’t have any brothers or sisters. Horses were always my favourite, though. I used to pretend that I was riding a horse in the porch at home, and I made a beeline for any horses and donkeys I spotted when we were out. Finally, when I was eight years old, Mum let me start riding lessons at the local stables and I was overwhelmed with excitement. It was the best thing that had ever happened to me in a life that was pretty good already, and I took to the saddle like a duck to water. I wasn’t spoiled, mind – I’d be swiped on the back of the legs with a hairbrush if I was misbehaving – but I was very, very loved.

Although I was christened Paulette, Dad called me his little ‘Cherryanna’ and the name stuck. Soon it was only teachers who called me Paulette and to everyone else I was ‘Cherry’. I called him ‘Pop’, and I was definitely a daddy’s girl, who cherished the time I spent with him. Each morning before breakfast we’d go out into the garden and walk round, inspecting the pond, deadheading the flowers and checking to see what had ripened in the vegetable patch. He’d pull up some carrots, wipe one on his hankie and hand it to me, saying, ‘Eat that, Cherryanna!’ In autumn he’d stretch up and pluck me a rosy apple from the tree, polishing it on his sleeve till it shone. When we went back indoors for breakfast, he’d sit on the stairs and carefully clean the mud from my shoes for me. Then on Sunday mornings, when he wasn’t in a rush to get to work, I’d climb into their bed and Pop would bring up tea and chocolate biscuits and play ‘camels’, with me sitting on his knees and riding up and down.

He was a talented carpenter, and one of my most prized possessions was an elaborate doll’s house he made me, a bungalow with a garden around it, and when you took the roof off you could see all the furniture inside. It was so detailed that there was even a little sundial in the garden, just as we had in our own garden.

I’m a visual person and all these memories are vivid pictures I carry around in my head, pictures that bring a sense of warmth and happiness and belonging. I also have a clear picture from the age of eight of a time when Mum and I were out sitting by the pond in the garden. I noticed her skin was all yellow and I said, ‘Mum, you look like a Chinaman.’* Later I overheard her repeating my comment to Pop and both of them laughing, but I couldn’t understand why it was funny. No one ever mentioned the words ‘liver cancer’ to me, not till I was much older, and I wouldn’t have known what they meant anyway.

A few weeks later, Mum had to go into hospital and I was taken to stay with some family friends, the Davidsons. I was quite happy there because I liked their son Donald, who was the same age as me; we did ballet at school together, co-starring in a production of Sleeping Beauty. I was going through a stage of feeling that I would rather be a boy than a girl, and Donald and I were great pals. As an only child, it was just nice to have another child in the house, someone I could play with. Mr Davidson had a film projector and we all sat and watched films in the evenings, which was great fun. I was so grateful to them for letting me stay that I tried to cook them breakfast one morning on their gas stove. In retrospect it must have been rather alarming for the family – but at least I didn’t set the kitchen on fire.

I was happy enough, but in the back of my head there was a niggling worry: if Mum was ill enough to have to spend so much time in hospital, how would she ever get well again? I didn’t ask anyone. I just tucked that worry inside me and carried on.

Children weren’t allowed on hospital wards in those days so I couldn’t visit, but once Pop drove me to the outside of the hospital and Mum came to a window near the top of the building and waved hard. She was just a tiny silhouette but it was reassuring to see her; she could still stand up and she could still wave. Hopefully that meant she wasn’t too sick after all.

And then, just after my ninth birthday, Mum was allowed home from hospital and I was taken over to our house to see her. She was lying on her side of the bed in her pink flannelette nightdress, so I clambered up onto Pop’s side to chat to her. There were tubes coming out of her stomach and she seemed all puffy and bloated, with pale, waxy skin. There were two bedside tables Pop had made from wood he had recovered from the bombed-out house in Hayes, and they were covered with medical paraphernalia: kidney dishes, syringes, pills and the like.

‘Are you better now, Mum?’ I asked, although I could tell by looking at her that she wasn’t.

‘No, darling,’ she said quietly, her voice all hoarse and breathy. She seemed very weak, as if talking was a big struggle.

‘Can I come back and stay at home with you?’

‘Not yet. You’re having fun at the Davidsons’, aren’t you?’ Pop was trying to sound cheerful without much success.

I looked at the Greek key pattern of the oak headboard and listened to the rasp of Mum’s breathing, trying to think of something good to say, something to make her feel better. Suddenly I had an idea. I jumped off the bed and ran round to her side of the bed, planning to give her a cuddle.

‘Careful!’ Pop said, putting out an arm to stop me, but not before I got round and saw that there was a white ceramic bucket full of dark red fluid on the floor, into which the tubes from Mum’s stomach were draining. It didn’t faze me as I’ve never been squeamish, but I had to watch not to kick it over.

‘Can I give you a hug, Mum?’ I asked. I couldn’t work out how I would get my arms around her with all those tubes in the way.

She glanced at Pop and he replied: ‘Not today, Cherryanna. Mum’s feeling a little bit sore.’

He drove me back to the Davidsons soon after and I remember feeling very subdued. Mum had looked so tired and ill, and it wasn’t like her not to give me a hug: she had always been a very tactile mum, someone who would let me climb onto her knee and snuggle up, breathing in her scent of 4711 Cologne and home baking. Now the smell around her was sharp and antiseptic and I didn’t like it at all. Nothing felt right. Even Pop seemed distracted and not his usual friendly self.

At the Davidsons, I shared a bed with Rosalind, the daughter, who was a bit younger than me. It was a big old bed with an eiderdown on top. A few days after seeing Mum at home, I woke suddenly in the middle of the night and I swear I saw Mum standing at the foot of the bed. I wasn’t afraid; I just looked at her, wondering what she was doing there.

‘Don’t worry,’ she said. ‘I’m an angel now but I’ll still watch out for you. I will always be with you.’

I’m not sure if the voice was out loud or in my head – Rosalind didn’t wake up – but I remember it very clearly, even today. Back then, in my nine-year-old’s head, I knew it meant that Mum was dead and had gone to Heaven. I wasn’t afraid of death because I went to Sunday school like all little children did in those days, and I believed in God and Jesus and angels in glowing white dresses with wings.

Mum’s angel didn’t have wings or a white dress. It was just her. It all seemed so normal that I just accepted it. She lingered at the foot of the bed for a while then faded away, and I lay awake, wondering when I would see her again and what would become of me now.

* This term, which sounds racist nowadays, was in common use at the time.