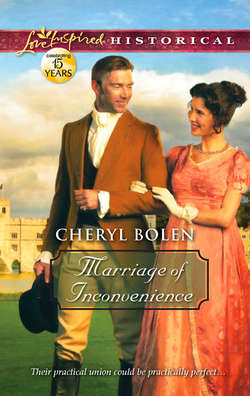

Читать книгу Marriage of Inconvenience - Cheryl Bolen - Страница 9

ОглавлениеChapter One

London, England

1813

The hackney coach slowed in front of Lord Aynsley’s townhouse. With her heart pounding prodigiously, Miss Rebecca Peabody pushed her spectacles up the bridge of her nose and drew a deep breath as the driver assisted her from the carriage. She paid him, glanced up at the impressive four-story townhouse, then climbed its steps and rapped at the door’s shiny brass plate. Almost as an afterthought, she pulled off her spectacles and jammed them into her reticule. Though she abhorred going without them due to her inability to see, she had decided just this once it was necessary. One who wished to persuade a virtual stranger to marry her must, after all, make every effort to look one’s best.

She felt rather like a convict standing before King’s Bench as she waited for someone to respond to her knock. Soon, a gaunt butler with a raised brow opened the door and gave her a haughty stare.

“Is Lord Aynsley in?” she asked in a shaky voice. She had particularly selected this time of day because she knew it was too early for Parliament.

The servant’s glance raked over her. Though her dress was considerably more respectable than a doxy’s, he must still believe her a loose woman because no proper lady would come to his lordship’s unescorted. But, of course, she could hardly have brought Pru with her today. One simply did not bring one’s maid when one wished to propose marriage.

“I regret to say he’s out,” the butler said. There was not a shred of remorse on the man’s face or in his voice.

She had not reckoned on Lord Aynsley being away from home. Now everything was spoiled. Such an opportunity might never again be possible once it was discovered she’d sneaked out the back of her dressmaker’s, stranding her poor maid there. All likelihood of ever again disengaging herself from either her sister, Maggie,

or Pru would be nonexistent. And to make matters even more regrettable, the hackney driver had left! She fought against tears of utter frustration. Perhaps the butler was merely protecting his master from tarts. She drilled him with her most haughty stare (though he was nothing more than a blur, due to her deficient vision) and said, “You must inform his lordship that I come from the foreign secretary, Lord Warwick.” Which was true, but misleading, given that her sister was married to Lord Warwick, and Rebecca made her home with them.

“I would convey that to Lord Aynsley were he here, but he is not. Would you care to sign his book?”

Owing to the fact she had not anticipated his lordship’s absence, she hadn’t given a thought as to how she should proceed were he not at home. Should she sign his book with a cryptic message? Should she merely leave her card? Should she ask him to call on her? No, not that. Maggie would never allow her to be alone with the earl, and in order to propose marriage, Rebecca must have privacy.

She decided to sign his book.

The unsympathetic butler allowed her to step into the checkerboard entry hall and over to a Sheraton sideboard beneath a huge Renaissance painting. Lord Aynsley’s

book—its pages open—reposed on the sideboard.

Though it was undignified to remove a glove, she did so before picking up the quill. This was her last pair of gloves that was free from ink stains, and Maggie had persistently chastised her about her endless destruction of fine, handmade gloves.

As soon as she divested herself of her right glove, she heard the front door swing open and a second later heard his voice.

“Lady Warwick!” Lord Aynsley said, addressing Rebecca’s back. “How may I be of service to you?”

Oh, dear. Because he saw her from the back, he would think she was her beautiful sister, whom he had once wished to marry. Drawing in a deep breath, Rebecca whirled around to face him, a wide smile on her face.

His face fell. “Miss Peabody?”

“Yes, my lord. I beg a private word with you.” How she longed to jam on those spectacles and give the peer a good look over. It had been so long since she last saw him, she couldn’t quite remember what he looked like. Truth be told, she had never paid much attention to him. At the present moment she wished to assure herself that his appearance was not offensive. But the only thing she could assure herself of was his blurriness—and that he was considerably taller than she and still rather lean.

A hot flush rose into her cheeks as she perceived that he gawked at her single naked arm, then he recovered and said, “You’ve come alone?”

She duplicated her haughty stare once again. “I have.” She gulped. “A rather important matter has brought me here today.”

“Then come to my library where we can discuss it.”

She followed him along the broad hallway past a half dozen doorways until they came to a cozy room lit by a blazing fire and wrapped with tall walnut cases lined with fine leather books. A much finer library than Lord Warwick’s, she decided. Another recommendation for plighting her life with Lord Aynsley.

“Oblige me by closing the door,” she challenged as he strode toward his Jacobean desk.

He stopped, turned to gaze at her and hitched his brow in query. “I’m cognizant of your unblemished reputation, Miss Peabody, and I don’t wish to tarnish it.”

“My unblemished reputation is exactly why I’m here today, my lord.”

“I’m sorry. I don’t follow you.”

“Please close the door and I shall explain.”

His gaze bounced from her to the door. He did not move.

Was he afraid she would damage his sterling reputation by intimating that he behaved in an ungentlemanly manner? “I assure you, Lord Aynsley, I have no aspirations to make false accusations against you.”

“You have roused my curiosity, Miss Peabody.” He crossed the room and closed the door. “Please sit on the sofa nearest the fire.”

She did as instructed, then wadded the missing glove into a ball concealed in her fist and hoped he would not notice her breach in decorum.

He came to face her on a silken plum-colored sofa that matched the one she sat on. “It’s quite remarkable how much you look like your sister.”

“That, my lord, is another reason why I’m here today.”

“I’m afraid I don’t comprehend, Miss Peabody.”

“Allow me to explain. You were once so attracted to my sister, you asked her to marry you.”

He nodded. “Your sister is a most beautiful woman.”

She drew a long breath, counting to five, then plunged in. “Then you must be satisfied with my appearance, my lord, for we look vastly similar—except for my deficient vision which necessitates my spectacles.” If only she could believe that. She was no beauty like Maggie.

Because his lordship was nothing more than a blur, she was unable to observe his reaction to the illogical trajectory of her conversation. The man was apt to think the most deficient thing about her was not her vision, but her mental capacity.

After a mortifying lull, Lord Aynsley recovered and answered as would any well-mannered gentleman. “You’re a most lovely girl.”

She glared at him. “I am not a girl. I’m a woman of eight and twenty. I came out of the schoolroom more than a decade ago, and in most quarters I’m considered past marrying age. That is why I’ve selected you.”

He did not say anything for a moment. “Pray, Miss Peabody, I’m still not following you. For what purpose have you selected me?”

“Before I get to that,” she said, opening her reticule, stuffing in the glove and pulling out a folded piece of parchment, “I should like to mention the points on my list here.”

While she unfolded the list she could see that he crossed his arms and settled back to listen.

Her glance fell to the list, but she was unable to read the now-fuzzy letters. She would have to recite from memory. “Not only do I greatly resemble my countess sister, but I’m a reputed scholar. I read and write Latin and Greek and am fluent in French, German and Italian. I’m exceedingly well organized and capable of overseeing a large household.” She paused to sit on her naked hand, hoping the earl had not noticed it. Lord Aynsley was a most proper peer, and she was most decidedly improper to be sitting here not only without a chaperone but also with a naked arm.

“The most important thing on my list,” she continued, “is that I absolutely adore children. I dislike the city and would love to live in the country—surrounded by said children. I have decided to marry a man a bit older, a man whose children need a capable mother. I shouldn’t mind at all if it wasn’t a real marriage. I suppose an older man would not still fancy the romantic aspects of marriage.”

No man who’d ever loved Maggie could be attracted to Rebecca. She understood that. She would never be able to experience a marital bond like Maggie shared with Warwick. Men just didn’t feel that way toward her.

“Dear heavens! How old do you think I am?”

She gazed up at him, but of course could not really see him without her much-needed spectacles. “Five and forty?”

“I am three and forty, Miss Peabody, and have no desire for a wife.” He stood abruptly.

“I beg that you sit down and hear me out. I’m not finished.” It was really the oddest thing how this idea of marrying Lord Aynsley had taken ahold of her. Her desire to wed the earl had nothing to do with his desirability and everything to do with her need to leave Lord Warwick’s house before she destroyed his heretofore

loving marriage to her sister.

Another strong impetus to marry was the prospect of liberating herself from the strictures of society that rather imprisoned an unmarried lady.

And she was devilishly tired of people pitying her as the old maid aunt to Maggie’s darling boys.

Though Miss Rebecca Peabody was void of passionate feelings toward any man, she was possessed of a great deal of passion, all of it channeled into the radical political essays she wrote under the pen name P. Corpus. Ever since the day she’d read Thomas Paine’s Rights of Man she had felt that expansion of civil liberties was her life’s calling. She’d even come to understand—against her initial resistance—that she was meant to leave America and come to England. It was only right that an American like she should show these snooty British just how antiquated—and oppressive—their government was.

It was her forward thinking that continually pitted her against Lord Warwick and the Tory government he served. Last night’s argument over his government’s resistance to labor unions had been the final straw.

She could not coexist with a man who upheld the wretched Tories’ elitist principles—or, in her opinion, lack of principles. How could a man like Lord Warwick—who was so good to his wife, his children and his servants, who read his Bible every day and went to church every Sunday—not follow his Savior’s command to treat the least of his brethren as he would treat Jesus?

The government should serve all its people—not just the wealthy landowners. How could the Tories think it right to repress men who needed to earn enough to feed their families? It wasn’t as if the wealthy, landed Tories would be destitute if they allowed modest increases in their workers’ wages.

She was certain the Heavenly Father had guided her to P. Corpus; therefore, He must be guiding her to this proposed marriage. It had become increasingly difficult to post her essays to her publisher without being discovered. A married woman would not have to be constantly watched by her well-meaning sister or her ever-present maid, neither of whom could be allowed to learn of her P. Corpus identity.

As a married lady, she could pursue her writings—and even be at liberty to write that full-length book on a perfect society, the book that was her life’s goal.

A pity she could not own the authorship of her essays, but doing so would jeopardize Lord Warwick’s career. Were it to be discovered that a woman living under his roof—a woman who had been an American colonist, no less!—so opposed the Tory government he represented, his distinguished career could be destroyed.

Lord Aynsley eased back into his chair without breaking eye contact with her.

“I know eight and twenty may seem young to you, my lord, but I assure you I’m very mature. Your seven children need a mother, and such a charge would be very agreeable to me. I also possess the capabilities to smoothly run a large household. You could attend to your important work in Parliament, secure in the knowledge that your competent wife was promoting domestic harmony in your house.”

He began to laugh a raucous, hardy laugh.

Even if the spectacles would obscure her resemblance to her beautiful sister, she must put them back on. It was imperative that she be able to see the expression on his lordship’s face. She opened her reticule and whipped out the two spheres of glass fastened together by a gold wire and slammed them on the bridge of her nose.

That was better! She could see quite clearly that Lord Aynsley was indeed laughing at her. It was also evident that he wasn’t so very old after all. Granted, a bit of gray threaded through his bark-colored hair, but the man was possessed of a rather youthful countenance. The man also had a propensity to always smile. “How dare you laugh at me, my lord!”

He sombered. “Forgive me. I mean no offense.” He cocked his head and regarded her. “Do I understand you correctly, Miss Peabody? You believe I might wish to make you my wife?”

Her dark eyes wide, she nodded.

“Pray, what makes you think I even desire a wife?”

She squared her shoulders and glared. “You asked my sister to wed you.”

“That was two years ago when I was freshly widowed and rather at my wit’s end as to how to run a household of seven children, a ward and an eccentric uncle.”

“You’re no longer at your wit’s end? Your children no longer run off governesses?”

He sighed. “I didn’t say that. It is still difficult to manage my household, but the task is less onerous now that my next-to-eldest—my only daughter—is a bit older.”

“How old is she?”

“Almost eighteen.”

Rebecca could see she would have to convince him that his womanly daughter was due to take flight at any moment. “Is that not the age when most young ladies choose to take husbands? Do you aim to keep her always with you?”

He did not respond for a moment. For once, the smile vanished from his face. “As a matter of fact, it’s my hope that my daughter will come out this year.”

“And if she chooses to marry? Who, then, will manage your household?”

“I shall cross that bridge when I come to it.” He peered at her with flashing moss-colored eyes. “One thing is certain, Miss Peabody. If I do remarry, I shall choose the wife myself.”

“But, my lord, you chose my sister, and that did not work out.”

“I have explained why I felt obliged to offer for your sister.” He stared at her, no mirth on his face.

“Does it bother you that I’m not yet thirty, and you are over forty?”

His smile returned. “My dear Miss Peabody, my father married my mother when he was six and thirty and she was eighteen, and theirs was a deliriously happy marriage.”

“As was my parents’. Papa married Mama—his second wife—when he was forty, and she was but twenty. And Mama was an excellent mother to my half brother.”

“As I’m sure you will be a fine stepmother to some man’s children, but I am not that man.”

How could she have thought a man with all of Lord Aynsley’s attributes could ever be attracted to an awkward spinster like she? Now that she had thoroughly humiliated herself, she must leave. “I’m sorry I’ve wasted your time, my lord.”

As she strode to the door, he intercepted her, placing his hand on her bare arm.

“Forgive me, Miss Peabody,” he said in a gentle voice. “I’m greatly flattered by your generous offer, but I must decline.”

“You’re making a grave mistake, my lord.” Then she yanked open the door and left, determined to walk all the way back to Curzon Street. Unchaperoned.

But how would she explain her brash behavior to Maggie? Sneaking out the back door of Mrs. Chassay’s establishment was bad enough, but it would be far worse if Maggie learned of her brazen, unchaperoned visit to Lord Aynsley’s.

* * *

Though he had planned to finish reading the articulate plea for penal reform penned by P. Corpus in the Edinburgh Review, John Compton, the fifth Earl Aynsley, could not rid his thoughts of the peculiar Miss Rebecca Peabody. Until today he had scarcely noticed the chit. In fact, he doubted he’d even laid eyes on her since the disastrous lapse in judgment that had caused him to offer for her sister some two years previously.

He raked his mind for memories of the bespectacled girl, but the only thing he could remember about her was that she perpetually had her nose in a book. No doubt such incessant reading had ruined the poor girl’s vision.

Normally he did not find females who wore spectacles attractive, but Miss Peabody was actually...well, she was actually...cute. There was something rather endearing about the sight of her spectacles slipping down her perfect little nose.

Of course he was not in the least attracted to her.

And he did not for a moment believe she was attracted to him.

After pondering her offer for a considerable period of time, he thought he understood why she wished to marry him. The chit seemed intent on removing herself from the marriage mart. She was not the kind of girl who held vast appeal to the young fellows there. By the same token, the young bucks there were not likely to appeal to a bookworm such as she. He believed she just might be more suited for a man who’d lived a few more years, a man who was a comforting presence like an old pair of boots. It took no great imagination to picture the bespectacled young woman with the flashing eyes merrymaking with children. But, of course, not his children.

It was while he was sitting at his desk thinking of the dark-haired Miss Peabody—and admittedly confusing her with her stunning sister—that Hensley rapped at his library door. “I’ve brought you the post, my lord.”

Aynsley was thankful for a diversion. The diversion, however, proved to be a single letter. From his daughter. A smile sprang to his lips as he contemplated his golden-haired Emily and broke the seal to read.

But as he read, the smile disappeared.

My Dearest Papa,

It grieves me to inform you that we’ve once again lost a governess. This time it was worms in her garment drawer that prompted Miss Russell’s departure. And if this news isn’t grievous enough for you, my dear father, I must inform you that the housekeeper has also tendered her resignation—owing to Uncle Ethelbert’s peculiar habit.

I shan’t wish for you to hurry back to Dunton Hall when you’ve so many more important matters that require your attention in our kingdom’s government. Please know that I shall endeavor to keep things running as smoothly as possible here until such time as you are able to secure new staff.

I remain affectionately yours,

Emily

He wadded up the paper and hurled it into the fire.

Now he was faced with the distasteful task of trolling for and interviewing a packet of females to replace the latest in a long line of governesses and housekeepers. If only he did have a wife to share some of his burden.

But he wanted much more than a well-organized scholar for a wife. He thought of his parents’ marriage, remembering when his mother would read over the text of his father’s speeches to Parliament, offering suggestions. They read Rousseau and Voltaire together, and shared everything from their political philosophy to their deep affection for their children. It was almost as if their two hearts beat within the same breast.

He had never had any of that deep bond with Dorothy—except for their love of the children—and he’d always lamented the void in their marriage. As he lamented other things void in their marriage.

He wanted more than a mother for his children and a competent woman to run his household. He craved a life partner. He’d been lonely for as long as he could remember—not that he would ever admit it. With none of his closest friends was he at liberty to discuss his forward-

thinking views. If he ever did remarry, it must be to a woman whose interests mirrored his own, a woman who cared deeply for him and his children, a woman whom he could love and cherish.

Such a woman probably did not exist. He took up his pen to dash off a note to his solicitor. Mannington would have to start the process of gathering applicants for the now-open positions on his household staff. But as Aynsley tried to write, he kept picturing Miss Peabody, kept imagining her with little Chuckie on her lap, kept remembering that sparkle that flared in her dark eyes when she challenged him. Most resonating of all, he kept hearing her words: you are making a grave mistake.

Unexplainably, those words seemed prophetic, like a critical fork in the roadway of his life. As he wrote his few sentences to Mannington, he kept hearing those parting words of hers.

Could it be that he ought to take heed? What harm could there be in trying to learn more about the unconventional Miss Peabody?