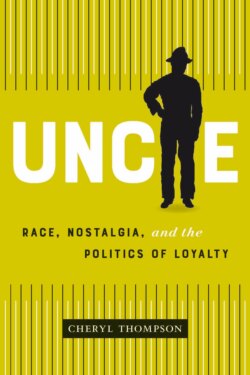

Читать книгу Uncle - Cheryl Thompson - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

1

UNCLE TOM’S CABIN

ОглавлениеPublished nearly 170 years ago, Uncle Tom’s Cabin is still known to people of different ages, classes, locations, and even languages. It first appeared in the U.S. as a serialized work of fiction, a chapter at a time, starting June 5, 1851, in the National Era, a weekly abolitionist newspaper edited by Gamaliel Bailey. Stowe’s book not only had a profound impact on American slavery; it also went on to become the bestselling novel of the nineteenth century, and the second bestselling book of that century (after the Bible).

Today, we do not necessarily think of novels as shaping national identity. However, in nineteenth-century America, the experience of reading fiction helped form the way people saw themselves in relation to their nation. Throughout the first half of the nineteenth century, most of the books Americans read were British, while only a small number of American writers were published in Britain.

Uncle Tom’s Cabin was one of the first American examples of the sentimental novel, which is characterized by its intention to elicit emotional reactions from readers by putting characters in pitiable situations. Early sentimental novels were brought to the U.S. in the eighteenth century from Britain. Initially, critics felt such novels would corrupt and delude readers with extravagant fancies. As a result, they often included a preface that asserted its pages contained ‘useful knowledge’ and a ‘truthful’ record of life.1 The sentimental novelist conscientiously took on the role of moralist and purported to be a truth teller. Consequently, this genre, more so than an earlier generation’s novels, captured the public’s imagination, especially with respect to social issues such as slavery, abolition, gender, and class.

With characters who crossed racial and class boundaries, Uncle Tom’s Cabin would have been seen by American readers as both a sentimental novel and an anti-slavery text, one that appealed to men and women alike. Using romantic literary devices, such as its focus on morality and religion, Stowe encouraged white readers to identify with the Black characters in her book. For the first time in an American novel, she portrayed slaves as moral human beings who suffered inhumane indignities and felt the same pain and anguish that whites would have felt.

Sentimental novels like Uncle Tom’s Cabin may have galvanized the abolitionist cause, but they did not refute widely held beliefs about the supposed inferiority of Black people. In the early nineteenth century, biological racialists – including phrenologists, craniologists, physiognomists, anthropometrists, ethnologists, polygenesists, and Egyptologists – sought to establish innate biological differences between whites and Blacks. Contrary to eighteenth-century race theorists, who generally attributed racial distinctions to environmental conditions, this new breed of scientist was eager to not only document differences between the races but also to ‘prove’ the moral and intellectual superiority of the Anglo-Saxon race. Some nineteenth-century scientists such as British ethnologist James Cowles Prichard even sought to show that Black people’s heads were covered with wool rather than hair.

Armed with these ideas, many antebellum readers would have closely followed Stowe’s sentimental instructions on how to ‘feel’ for the enslaved figures depicted in her novel. Yet while they may have sympathized with the ‘poor slaves’ in the text and used her story to renew their Christian faith, most white American readers at the time would have also maintained their sense of superiority.

For sentimentalism to function as a public instrument capable of stirring an audience to social action, it must evoke an emotional response, which Uncle Tom’s Cabin did by depicting the brutality of slavery. But as Barbara Hochman, author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin and the Reading Revolution, writes, some white readers related to the book to a degree that Stowe probably would not have approved of, ‘temporarily collapsing the imaginative distance between themselves’ and the novel’s enslaved characters.2 While some readers lost all sense of self and reality while reading Uncle Tom’s Cabin, the novel also served as an education for many people about slavery. Along the way, it triggered a lot of anxiety about Black literacy and self-emancipation.

Full-page illustration of Eliza and Tom by Hammatt Billings for the first edition of Uncle Tom's Cabin (1852).

Two of Uncle Tom Cabin’s most important Black characters knew how to read. When George Harris, a highly inventive figure, runs away from his resentful master and is prepared to kill for his freedom, his masculinity seems untameable. Uncle Tom himself is also literate, the Bible being his primary text of choice, yet he has no desire to run. The duality between loyal Tom and disloyal George undoubtedly signalled to white readers that while slave literacy could lead to faith and self-control, it also posed a dangerous risk.

By the time Stowe published the novel, numerous slave narratives had already established a link between literacy and escape or rebellion. Her earliest readers may have remembered the slave rebellions of the 1830s, when Nat Turner, a highly literate enslaved preacher, set off a two-day uprising by both enslaved and free Black people in Southampton County, Virginia, in 1831. Virginian authorities responded with a brutal crackdown, and the event left many Southerners with a fear of the literate enslaved man.

In sum, Uncle Tom’s Cabin not only satisfied the public’s desire to understand the institution of slavery from the fictionalized slave’s point of view, it also tapped into the South’s desire to defend slavery. In so doing, Stowe’s novel may have contributed to some of the fears around African American freedom. Namely, the idea of African American escape was tantamount to Southern planters losing their livelihoods, which were dependent on free labour.

While the novel dealt directly with the prevailing issue of the times – slavery and its horrors – it also spoke to America’s North-South divide. Northerners had increasingly become anti-slavery abolitionists by the 1850s, even as white Southerners remained economically, socially, culturally, and psychologically wedded to an institution that was, by this time, both unprofitable and increasingly unsustainable.

As Sven Beckert, a Harvard University historian and author of The Empire of Cotton, explains, ‘American slavery had begun to threaten the very prosperity it produced, as the distinctive political economy of the cotton South collided with the incipient political economy of free labor and domestic industrialization of the North.’3 Since the world was invested in the U.S. production of cotton, it is not surprising that a novel about the lives of the enslaved resonated around the world, and especially in Britain, where the abolitionist movement was strongest outside of the United States.

In May 1852, Uncle Tom’s Cabin was published in London; within a year, there were twenty-three different editions. According to Michael Pickering’s history of minstrelsy in Britain, the novel was available at every book stall in Britain, and by the end of that year, 1.5 million copies had been sold across the country and its colonies. Soon there were a dozen dramatizations of the book, as well as four different Uncle Tom pantomimes on the London stage.4

Thanks to the novel’s runaway popularity, millions of people encountered relationships and characterizations of American slavery unfamiliar to them. With the characters of the enslaved Topsy and the privileged Eva, Uncle Tom’s Cabin established what historian Robin Bernstein calls a ‘black-white logic’ in the American vision of childhood.5 When Topsy, a dark-skinned ‘pickaninny,’ is purchased by Augustine St. Clare at auction, she becomes Eva St. Clare’s playmate. After Topsy is caught stealing, Eva is determined to help her become a moral little girl. Eva encourages Topsy to be honest with her, and thus begins the St. Clare family’s quest to teach Topsy how to love – because they believe she has never been able to do so. Eva’s innocence engulfs Topsy. Yet the polarization between these two versions of childhood pits them against one another. While both were innocent children, the violence of slavery, Stowe suggests, is an attack on Topsy’s natural innocence, which can be partially restored through the loving touch of a white child, Eva.

Discovery of Nat Turner, wood engraving by William Henry Shelton, 1831.

Stowe’s vision of Uncle Tom constructed a form of Black manhood that similarly required service to whites. Black men were often denied the rights of manhood; for example, enslaved Black men were regularly referred to as ‘boy’ – regardless of their age – a practice that continued through the Jim Crow era. As such, it was typical of literary uncles before the Civil War to be deferential to white authority. This kind of characterization ultimately suggested that Black manhood could be achieved only by staying in one’s place – i.e., through servitude. Despite being ripped from his wife and children, chained, and sent off in a coffle with other miserable chattel, let down by even a good master, and beaten, finally to death, Uncle Tom does not ever speak ill of anyone. Stowe also depicts him as a man in the prime of life: dark haired and broad shouldered, which was a typical depiction of Black men before the Civil War. As Jo-Ann Morgan, author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin as Visual Culture, writes, ‘Before emancipation, a few other dark-haired, broad-shouldered adult Black men had appeared in print. Images of one escaped slave, holding a rifle and standing tall, was inspiring propaganda to justify the war for Northern readers of Harper’s Weekly.’6 Antebellum readers would have recognized Uncle Tom as a noble and self-sacrificing figure, traits that were seen as ‘good’ to white abolitionists.

Captive Uncle Tom, then, was a hero – a devout and pious Christian who will not be swayed from his faith, even at the peril of bodily harm and death. In fact, Stowe presented Uncle Tom as a Christ-like figure. Like Jesus, he suffers agonies inflicted by malicious secular people. And like Jesus, Uncle Tom sacrifices his life for the sins of humankind, to save his oppressors as well as his own people. However, his martyrdom goes hand in hand with his symbolic emasculation. By turning Uncle Tom into Eva’s patron-friend, Stowe intellectually and sexually castrates him. Uncle Tom might have been a hero to most white readers, but for many Black readers, he was an anti-hero. His passivity disavowed Black agency and discouraged Black aggression. If Uncle Tom chooses to acquiesce to his own subordination and yet remains the novel’s hero, where did that leave Black men who resisted their oppression?

Simon Legree beating Uncle Tom, illustration, c. 1885.

However, within the context of the novel, both whites and Blacks look up to Uncle Tom. Yet his literary stature did not last. When profit-minded entrepreneurs and theatre producers lifted the character of Uncle Tom from the pages of Stowe’s novel and situated him on memorabilia, consumer goods, and eventually the minstrel theatrical stage, his character began its precipitous decline from hero to pejorative stereotype.

Uncle Tom’s Cabin was not just a work of abolitionist fiction penned by a writer fervently convinced that slavery was patently immoral. It also marked the beginning of a cultural, commercial, ideological, and theatrical phenomenon that would last long after the book dropped off the bestseller lists.

Shortly after the book was published, related merchandise flooded the market, including Uncle Tom soap, Uncle Tom almanacs and song-books, Uncle Tom wallpaper with panels representing key scenes in the story, and cute Topsy dolls for little English and American Evas to comfort and cherish.

Uncle Tom also influenced nineteenth-century fashions. In New York, gentlemen began sporting the ‘St. Clare hat’ – a reference to Eva’s father, the Southern plantation owner who buys Tom early in the story. Meanwhile, fashionable ladies bought ‘Uncle Tom tippets’ and scarves printed with scenes from the novel. According to accounts in the New York Illustrated News, ‘Eliza’ dresses were reported as the rage in Paris.7

At mid-nineteenth century, Uncle Tom’s Cabin existed only as a novel, but in the decades that followed, the novel morphed into a global sensation affecting consumer, visual, and literary cultures. The ‘Tom mania’ that would dominate the 1860s was driven by a combination of increasingly sophisticated consumer manufacturing technologies but also images. With technological advancements in lithographic printing, the circulation of images of Uncle Tom became just as important as his literary character.