Читать книгу Sea Monsters - Chloe Aridjis - Страница 16

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеON DAYS OF LESS POLLUTION ONE COULD SEE THE volcanoes there on the edges of our city, taunting and majestic, their contours carved by light, their slopes scaled by countless imaginations, even mine, especially at moments when I felt hemmed in. Needless to say, there were still plenty of scenes and vistas of which Tomás did not form part. Not even as an idea. It was important to have those too, and the most successful of these intermissions was an evening spent at the home of my friend Diego Deán, punk rock singer, draftsman, and occasional shaman.

A small gathering, he’d called it, which it was in size but not tenor, our festivities conducted under the gaze of his three iguanas, who blinked warily each time a new guest arrived. Diego had produced hundreds of sketches, from all angles and perspectives, of his companions: frontal, profile, rear. He drew their prehistoric eyes, their lazy lids, their heavy blinks. These sketches hung on the walls between the bookshelves, and it was hard to tell where his pride lay most, with the drawings or the pets.

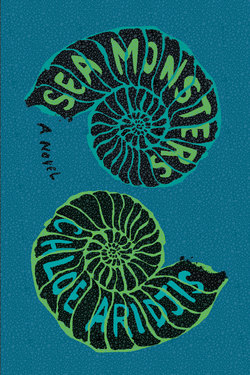

That night the creatures had watched us from their enclosures, tall glass tanks that loomed over the furniture in the living room. Someone put on a Klaus Nomi record while a large spiral of white powder was prepared on the coffee table, cards angled left and right creating whorls so thick it looked like the ghost of an ammonite, a logarithmic spiral like the ones from last year’s geometry class. Once the spiral was completed Diego rolled a fifty-peso note into a cylinder and helped himself to approximately two centimeters of powder. After inhaling he passed the note to the guy next to him, who repeated the action before passing it on. Eventually the rolled-up banknote reached me, its paper warm from so many fingers, and what could I do but join in the ritual.

The bold hum of voices, mostly male, rose and fell around me, everyone talking and thought-walking like Cantinflas, their voices expansive, compulsive, filling every inch of air. And soon I too felt charged, charged and restive and impervious to everything, and after two lines I rose from the sofa and marched over to one of the iguana tanks and stuck in my arm. But scarcely had my fingers touched the top of the scaly head than Diego rushed over and yanked my sleeve, saying I’d clearly never experienced the dinosaur teeth or dinosaur scratch or dorsal thwack of their tails, not to mention one should never approach an iguana from above, only from the side, otherwise they think they are under attack, and furthermore, it takes years to gain an iguana’s trust, he said with pride as the creature looked up at us with an indifferent eye.

Diego returned to the table, circling the spiral like a sinister jester. Someone turned up Klaus Nomi and for a moment the living room was transformed into an opera set and in my mind Diego Deán and Klaus Nomi became one. Diego could be Nomi without the makeup, it occurred to me, they had the same arched eyebrows and beaky nose and rosebud mouth. Then again, Nomi had recently died of AIDS in solitary conditions in New York, I remembered reading, people too scared of the new disease to even visit. Dark thoughts began to wash over me, the shadow side of drugs, which was why I didn’t venture there often, and I tried to sink into the sofa despite being too wired to properly sink, observing the dwindling spiral as every few minutes another whorl vanished, every guest part of the anti-helical operation that slowed down as we neared the center.