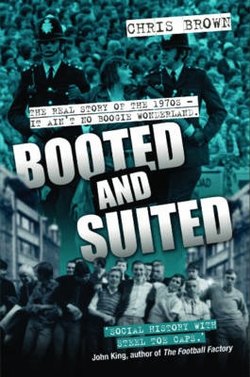

Читать книгу Booted and Suited - Chris Brown - Страница 20

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

A History Lesson

ОглавлениеI must have been ten, maybe eleven. Either way my physique wasn’t up to much. I came running in with a face full of hate and anger, demanding pity. Through the snot and the tears, I blubbed to my old man, ‘That… that older kiddy just hit me!’

‘Well, go and ’it ’im back,’ my father replied matter-of-factly. I detected a wink and a grin and did as I was told. The scene had been set.

As the dreamy, idealistic, liberal 1960s drew to an end, dear old Britannia, who had hitched up her skirt, kicked off her sandals and danced barefoot in the park with the rest of Timothy Leary’s peace-loving hippies suddenly received an abrupt dose of reality, and a reminder that she was not quite ready to lose her head and her customs to a bunch of junkies from across the pond.

The ‘hard mods’ or ‘peanuts’ had arrived as younger, more dysfunctional, hippy-hating cousins of the mods in early 1968 and by mid-summer the following year, the newly named ‘skinheads’ – after a short flirtation with the ‘cropheads’ moniker – had quickly taken over as the cult for the disenchanted, white working-class youths of Britain. It had been a long hot summer of mounting violence and thumping reggae. Desmond Dekker topped the charts and bovver boots stomped across the nation. The new decade was bracing itself.

January 1970. That Derrick Morgan record drifted unnoticed in the nether regions of the pop charts while Rolf Harris sung about his ‘Two Little Boys’. Crushed-velvet loon pants, flowers in the hair and ten-minute guitar solos were not for me. I was 14, a perfect age for a perfect era. In all honesty I wished I was older. I had observed and learned from the sidelines, pored over every tabloid newspaper screaming out in 72-point headlines, full of the daring deeds of my heroes rampaging through Margate and Weston, causing mayhem on every terrace in the country.

I’d had the regulation haircut, nicked my old man’s clip-on braces and sat in the bath wearing my Levi’s in a forlorn attempt to shrink them, resulting only in blue-stained legs and a bollocking from my mum. I’d furnished the end product with a neat half-inch turn-up, and on a visit to the ex-army stores in Hotwells Road I had purchased my suede zip-up bomber jacket and bought the boots. And these weren’t just any boots: 30 bob’s worth of ex-army leather and hobnails that were so big and heavy I had to walk three paces before they moved.

No wonder we walked in that distinctive way – the arrogant, bow-legged swagger, the arms thrust deep into pockets of short zip-up jackets or sheepskin coats, poking out at right angles, ready to annoy, aggravate, bovver anyone who dared to cross our paths. This was the only way to recognise a true skin – surprisingly not by the hair length, which varied in length from an admittedly rare number one to a more common short-back-and-sides. Nor by the boots for that matter, which were a fearsome and varied mixed of either ex-army hobnails, calflength NATO Paratroopers, Big T Tuf industrials or the ultimate, terrifying footwear, NCB steel-toe-capped real McCoys. The walk, that’s what identified the skin, the walk – once I had mastered the all-important ‘fuck-off-outta-my-way’ walk, I knew I had arrived.

I had arrived all right, arrived just in time for everything to change. In less than 12 short months, the skins had evolved. It was more a case of them having to: the law had declared steel toe caps and hobnails as offensive weapons and anyone found wearing them was likely to have them, or their laces, removed, or worse still, be arrested on sight. The hair, which was never as short as to truly warrant the tag ‘skinhead’, was growing and the clothes were getting distinctly smarter. The look, which had been as much about expressing your pride in your working-class background if not your fictional East End of London hardness with its collarless union shirts, granddad vests and everything ex-army, was being replaced by something altogether more cosmopolitan and more pragmatic, which the high-street clothes stores of Britain were more than willing to cater for.

Black, bottle-green and even Prince of Wales check Harringtons competed with blue denim and beige, needle-cord Levi’s and Wranglers in the jacket stakes, while brilliant-white Levi’s Sta-Prest, which in 1969 had been worn by every self-respecting bovver boy on a Saturday evening or on a Bank Holiday trip to the seaside, were now available in a myriad of colours including my own preferred choice, olive green. For practical reasons the commonest colours by far were bottle green or jet black. Practical, because you could wear them to school matched with your shiniest pair of Royal brogues which, with half an inch extra leather sole and steel ‘Blakeys’ added on for good measure, more than made up for your absent bovver boots. Crombies, with the obligatory handkerchief in the top pocket had begun to replace sheepskins, which most young skins couldn’t afford anyway, and the candy-stripe Ben Shermans were now available in a multitude of check patterns, as were the better-value and even more colourful Brutus or Jaytex versions, if your old lady thought £3 was too much to pay for the real thing.

Yeah, this was all right, I thought, I’ll have some of this. But the boots, we still needed the boots, what about the fucking boots? The old hobnails might make you look tough, but the only time I used them in anger, against some young Barnsley greaser on the terrace at the tail end of 1969, I went a pisser and got a right hiding. They were all right for showing off in school, running and sliding across the playground, impressing the young sorts with the sparks flying, but practical, comfortable footwear? Forget it! No, get yourself a pair of the new smart, showy eleven-hole Doc Marten Astronauts, or even the cutesy Monkey boot. For some unfathomable reason I decided on the Monkey boots. They looked great: shiny black, brown or Ox-blood with yellow laces. The only trouble with Monkey boots was that they came in small sizes so all the sorts could wear them, but I loved them, bought a pair in Ox-blood – what a name, even the polish sounded hard.

So this was it. Definitely arrived this time. Got my clothes, got my new haircut complete with a pencil-thin parting down the left-hand side, and got my mates. A decent crew really, headed up by Waddsy who just had to wear the cherry-red Astros, while Benny, Lil and me, Browner, sported the poor-relation Monkey boots. Sure there were plenty of other kiddies – Mogger, Harvey, Tommo, Smo – but we were the cream of the crop. Virtually all of our year in school were skinheads, at least the ones from the council estate. We had all read the book by Richard Allen and we could all recite the best bits verbatim from the book that bore that title.

Joe Hawkins was our hero. And did he, or even Richard Allen for that matter, really exist? Did they fuck! The day I found out that Richard Allen was in fact a 40-year-old Canadian by the name of James Moffatt and that Joe was a figment, albeit a very plausible one, of his overworked imagination was comparable to the day that I found out that the old fella dressed in red who came into my bedroom on Christmas Eve was not who he seemed. But who gave a fuck? Joe was the top man; anything Joe and his mates could do on the North Bank at Upton Park we could do on the Tote End at Eastville. We all looked the same, acted the same and followed the same rules; for Joe’s West Ham, read Browner’s Bristol Rovers; for Plaistow read Henbury. Not that we inhabited Joe’s nightmarish and brutal world. Ours was the real world and the inner-city strife, poverty and racial conflict of the slums of Plaistow were not something we experienced on a daily basis in the relative comfort of a north Bristol council estate that bordered on the edge of open countryside and enjoyed views of the wooded Blaise Castle estate.

Henbury, like the majority of council estates built in post-war Britain, was still populated mostly by honest, hard-working families, largely free of the serious crime and drug problems that would dog them in later years. The rows of neat gardens fronting the tidy houses with their gates and doors uniformly painted in standard council-issue colours of blue and green had a consistency about them that ensured no resident felt he was better, or worse, than his neighbour. Moreover, the rent that was paid in cash each week was at a level that most people could afford; indeed, the success of council house estates was a testament to the Labour Government that had created this utopian dream back in the 1950s. It’s a pity that, like Richard Allen’s novels, this was all bullshit, although admittedly it was only in later years when Thatcher and her cronies set out to end socialism, and consequently abolish the working class as Britain knew it, that the dream turned into a nightmare and degenerated into the oblivion of drug abuse and street crime that is still prevalent today. Furthermore, the individuals who subscribed to Thatcher’s beliefs convinced themselves they were no longer working class and rushed to buy their council houses, fit their Colonial doors and park their Sierras on their new driveways – in so doing depriving future generations of tidy, affordable housing – were as equally culpable as that scheming, misguided tyrant herself.

The drug use that was to become widespread on council estates in future years was virtually unheard of in the skinhead movement, and was regarded as the domain of the drop-out hippy and the loathsome greaser. The majority of skinheads abhorred drugs and, although their elder cousins, the mods, had imbibed performance-enhancing speed, purple hearts and the like, no self-respecting skin would partake of uppers, let alone the mind-expanding and hallucinatory drugs associated with the ‘far out man’ hippies.

If we weren’t able to boast about our tough inner-city upbringing, then at least we could emulate Joe and his mates in other ways. Admittedly, our version of street crime and aggro was generally confined to nicking reggae LPs from Jones’ department store, vandalising phone boxes and terrifying the local hippy population, which as it turned out was usually our fellow school pupils from leafy Westbury. We even dodged paying our bus fares, although our one and only incursion into racial abuse, when Waddsy abused the cheery West Indian conductor with a surly ‘I ain’t paying, wog’, resulted in him getting a smack in the mouth and us being unceremoniously turfed off the bus. We even fashioned our own weapons and ‘tooled ourselves up’, with sharpened steel rat-tail combs and six-inch lengths of sand-filled bicycle inner tubes, though these only got an airing when you rapped your mates’ knuckles round the back of the bike sheds while enjoying an illicit fag.

Life on the terraces, though, was an altogether different story. It was here that we came into our element and lived out our fantasy of being the hard men of the Tote End, Bristol Rovers’ (in)famous terrace. We rarely instigated the rucks, which kicked off with alarming regularity, but nonetheless we hovered like flies and mercilessly put the boot in with the best of them once an unfortunate visiting wretch found himself prostrate on the terrace. The Tote End was to become my stage where, hopefully, if I performed well and followed the script, I would become a star. But in 1970, participating only from the sidelines like the rest of my mates, I was nothing more than an extra, a bit-player. One, though, who was ever willing to learn from the real star turns and legends whom I studied, worshipped and longed to emulate.

I’d been a Rovers fan since 1968, in the days when ‘Ziggar zagger! Zigger zagger! Oi! Oi! Oi!’ bellowed out from the terraces. Unbelievably though, and to my eternal shame, my first ever football match was at Ashton Gate – Bristol fucking City versus Blackburn Rovers, 0–0, fucking crap. Was this really what they were eventually to call the beautiful game? I don’t know why I went to Ashton – peer pressure seems such a lame excuse. At the time, all the rest of the kids in our street were City fans, England were holders of the World Cup and every snotty-nosed kid the length and breadth of England wanted to be the next Geoff Hurst, George Best or, in Bristol’s case, the next John Atyeo or Alfie Biggs. Football, football, football, that’s all I wanted out of life; instead, I got some ponces in red shirts making arses of themselves, and to top it all it was south of the river.

Now that football has become accepted, a compulsory topic for the chattering classes to discuss over dinner, celebrity supporters will regale one another and seek each other’s approval for the reason they followed a particular club. ‘It was in my blood, my father took me to Highbury when I was only two days old’; ‘My great-uncle Ernie played for Liverpool’; ‘I’ve followed Manchester United even when they were bottom of the league’ (and just when was that exactly?). It was their destiny; bollocks was it mine! My old man was only concerned with putting food on the table and tending his fuchsias, while my older brother didn’t know the difference between a flat back four and flatulence.

‘Who do you support then, Dad?’ I had asked my old man, thinking I could stir up some inspiration from him. ‘City or Rovers?’

‘Neither, son,’ he said matter-of-factly, ‘they’re both crap.’

Couldn’t argue with that, they were crap, with City languishing at the foot of the old Second Division and Rovers middle of the Third. Still, it had been worth a try. No, the reason I changed my allegiance and became a die-hard, true-blue Rovers fan wasn’t destiny or fate or any other such claptrap that the latter-day middle-class supporters of the Premier League espouse. It was because, quite simply, Eastville Stadium, the home of Bristol Rovers, was on the bus route.

It was a rainy day in the middle of the winter of 1968. The opposition, some dreary northern-town cloggers. Our legendary beer-swilling, fag-smoking, grossly underrated centre-forward Alfie Biggs (now that’s what I call a footballer’s name) led the line for Rovers. And that’s about it – as much as I can remember about my first game at Eastville. I’ve always thought it odd, I can remember the opposition at Ashton Gate and the score in that first ever game, but not my first furtive fumblings with what was to become the love of my life. What I do recall, however, was the stadium. What a place, what an atmosphere, what an ambience, but, above all else, what a smell – it was near a gasworks. The permanent rain from the cooling tower that fell at Eastville even on the sunniest of days, permeated your clothes, your hair, even your skin. It was like a drug. I needed that intake of gas every fortnight and I couldn’t get enough of it. The place was nothing like Ashton Gate, which at that time was only covered on two sides. Eastville had a long and somewhat decrepit old wooden South Stand, a large and more impressive North Stand, a huge open terrace and the pièce de résistance, the covered Tote End. To me Eastville Stadium was the Wembley of the West Country.

Violence at football started simmering in the mid-Sixties. It was natural – working-class kids, bit of money in their pocket for the first time and easy access to the rest of the country through the ever-expanding motorway network and rail system. But what it needed to really take off was a catalyst, something to bring it all together and to unleash its full potential to the unsuspecting world. That catalyst had arrived in 1969 in the form of the skinhead. At last, a cult that was actually based on, and more importantly thrived on, violence. Sure, the mods weren’t opposed to the odd rumble at the seaside with the rockers, but the skinheads perfected the idea and found the obvious battleground to carry out their conquests every week, not just on Bank Holidays. But unlike all the other teenage cults that had troubled Britain over the previous 30 years, they had found their perfect and ever-ready enemy – each other.