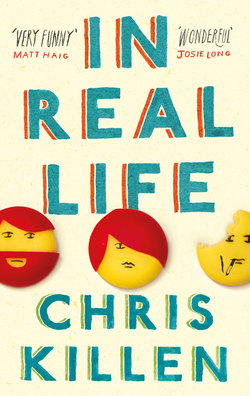

Читать книгу In Real Life - Chris Killen - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIAN

2014

My alarm goes off and I press snooze, then snooze again, and then, finally, I just turn it off and lie on my back, unable to get out of bed. I hear Carol go into the bathroom. I hear the flush of the toilet and the buzz of her electric toothbrush and the hum of her hair-dryer, and then, a little later, the slam of the front door.

On my way to the bathroom, I stick my head into the living room, which I didn’t really get a chance to look at properly last night. It’s just a small cream-coloured room with a leatherette sofa and an Ikea coffee table and a non-flatscreen TV in it.

I squat down in front of the little bookcase in the corner. There’s a shelf of DVDs (Along Came Polly, When Harry Met Sally, Bridesmaids) and below that, a shelf of self-help books (The Alchemist, Ways to Happiness, The Secret, etc.).

When we were teenagers, Carol used to listen to Sonic Youth and Nirvana. She used to read William Burroughs and have her nose pierced.

When did she get into all this shit? I wonder, sliding out one of the books and reading the back cover.

Are you lost? it says.

(Yep, I think.)

Are you seeking more purpose and direction in your life?

(Yep.)

Do you sometimes feel that you have perhaps strayed from your original path?

(Yep.)

If you have answered ‘yes’ to any of the above questions, then this book is for you! Simply carry on reading and let Jennifer McVirtue (PhD) be your guide on the path back to happiness.

I turn the book over and look at the front cover, a badly photoshopped image of a garden path with wispy fairies dancing up and down it.

I want to go home now, I think, not knowing quite where that is any more.

Before I leave the flat, I look at myself for a long time in the bathroom mirror, wondering what to do about my beard. Should I just trim it a bit with Carol’s nail scissors, or shave it off completely using the purple ladies’ razor on the side of the bath?

I make a growling face at myself and think: Would you employ this person?

(Probably not.)

So I pick up the nail scissors and start snipping.

As I’m doing my chin, I find six bright white hairs hiding amongst the black ones.

I keep thinking about what Carol said in the car: ‘Makes you look about fifty.’

I’m thirty.

I feel about a hundred.

In the city centre, there’s an even bigger HMV than the one I used to work for. Its shutters are down and there’s a big red ‘RETAIL UNIT TO LET’ poster tacked in the window. I stand outside it for a long time, smoking roll-ups and pretending to be waiting for someone.

When our branch closed, it was chaos.

On the last day, everyone left with handfuls of CDs and DVDs stuffed in their backpacks. I got home with mine and looked them up on eBay. Even brand new they were only worth about a penny each.

A little further down the street, a crowd has gathered round a small break-dancing boy. They clap and cheer as he spins on his head, then pops himself back up onto his feet. Still in time to the beat, he flips the baseball cap off his head and moonwalks around the front row of the crowd with it, flashing a gappy, milk-toothed grin as the hat fills with change.

I try to imagine myself busking: standing in the middle of this street, playing ‘Wonderwall’ or ‘Hey Jude’ or whatever it is the people of Manchester might want to listen to, and just the idea of it makes a queasy knot appear in my stomach. My guitar hasn’t been out of its case in almost two years. It’s been even longer since I actually played it and sang in front of anyone.

I start walking back towards the bus stops in Piccadilly Gardens. I dodge past the charity muggers and the phone-card people, pretending I don’t see them waving at me, almost all the CVs I printed out this morning still sitting at the bottom of my rucksack.

‘You sound tired,’ Mum says, on the phone that afternoon. ‘Are you sure you’re okay?’

I’m back in the spare room again, sitting on the bed, feeling sorry for myself. Earlier on, I tried to start Ways to Happiness, but I felt too sad to concentrate properly.

‘Don’t worry about me,’ I say, as not-tired sounding as I can. ‘I’m fine.’

‘Are you sure?’

‘I’m good. I feel good about things.’

Maybe it’s a bad connection, but Mum sounds older than normal on the phone today. She sounds like she’s made from bits of cobweb and flannel, and as I speak I can feel my throat swelling painfully.

‘Well, take care of yourself,’ she says.

I’m sorry, Mum, I think. I’m sorry I’ve not yet done anything in my life to make you proud of me. I’m sorry I’ve never been able to see anything through to the end. Don’t worry. Hopefully this is just a phase I’m going through and soon I’ll be absolutely fine, honestly. I really and truly feel like I’m right on the cusp of finding something good and rewarding that I want to do with the rest of my life, and right now is just a strange blip that we’ll soon be able to look back on and laugh about, or better still forget about completely, just you wait . . .

‘I’d better go,’ I say.

‘Make sure you’re eating well,’ she says.

‘Love you,’ I say, quickly hanging up the phone before she can say anything else.

‘Can I have a quick word?’ Carol asks, appearing so suddenly in the kitchen doorway that it makes me jump.

I’m halfway through the washing up. I’ve been trying my best to be helpful around the house, to not do anything to piss her off. I turn around and she’s holding the carrier bag we use as a bin in one hand and what looks like a food-stained till receipt in the other.

‘What’s up?’ I say.

‘Twelve mini chocolate croissants,’ she reads from the receipt. ‘Six raspberry jam doughnuts, one packet of Jaffa Cakes, three The Best ready meals, one bottle of Heinz brand tomato sauce, squeezy style . . .’

‘So?’ I say.

She raises an eyebrow.

‘What?’ I say, honestly confused.

‘So, do you know how much all this came to?’

I have no idea.

‘Twenty quid?’ I guess.

‘It came to thirty-six pounds sixty-eight.’

‘I don’t quite see what your point is,’ I say.

I’ve stopped doing the washing up now.

I’m just standing there with my hands in the water.

I imagine myself taking a plate out of the sink and smashing it against the counter top.

‘My point,’ Carol says, ‘is that you need to start saving money and stop buying brand names like a dickhead. How much do you have left in the bank, in total? Three hundred quid?’

‘Something like that.’

(It’s actually closer to thirty, but I don’t know the exact figure because I’ve been too scared to check my balance.)

‘You really need to start being more careful,’ she says.

‘I’m sorry,’ I say. ‘I’m just a bit of a mess at the moment. I’m not really thinking straight.’

I can feel my eyes becoming blurry and a buzzing warmth creeping up from my collar, so I turn back to the sink and pretend to do more washing up, but really I’m just putting my hands in the water and swishing them around to make noises.

I hear her screw up the receipt and stuff it back in the bin bag, then walk across the kitchen towards me. She rubs my arm and rests her head gently against my shoulder and I remain very still, like a rabbit. Beneath the water, I press my fingertip against the ridged blade of a bread knife.

‘You’ll be okay, you wally,’ she whispers.