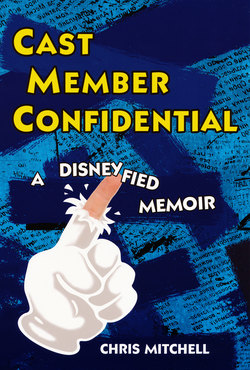

Читать книгу Cast Member Confidential: - Chris Mitchell - Страница 10

When You Wish Upon a Star

ОглавлениеWalter Elias Disney died alone. According to the reports, there was a physician on duty and some hospital staff nearby, but neither his wife nor his two daughters were present when he finally succumbed to “acute circulatory collapse” on December 15, 1966. This fact is one of the little proofs I cite in my arguments for atheism.

While he was alive and in charge of the theme parks, Walt was very particular about the appearance of his park staff, whom he re-branded Cast Members to make employment feel more like show biz. Among the many regulations in The Disney Look book I was violating were body piercing, facial hair, black nail polish. Men’s hair could not cover the ears or shirt collar, and sideburns could be no longer than the earlobes. After twenty-five years of stubborn rejection, Disney was finally allowing mustaches, but only the nonthreatening kind à la Tom Selleck, Keith Hernandez, or Ned Flanders. No beards. In my case, becoming a Disney Cast Member meant a transformation of near surgical proportions.

First stop: the barber shop, where a thin wisp of a man hacked my artistic locks into a style that my father would approvingly call sensible. With a creepy sense of familiarity, I realized that I was now sporting the same hairstyle as my brother, the stunt monkey, Nick, Donald Rumsfeld, and pretty much every moral majority nut job who ever complained about indecency in my articles.

Sensing an impending identity crisis, I headed back to the “World Famous” Budget Lodge in Kissimmee where I had secured an inexpensive roof over my head. The carpets reeked of suntan lotion and diaper powder, and I’m pretty sure the mattress was filled with stuffed woodpeckers, but it had hot showers and clean towels. Over a sink of soapy water, I extracted my labret for the last time and shaved my goatee. My reflection in the mirror looked like a twelve-year-old version of myself, before Glen Plake and Anthony Kiedis became fashion icons, before my brother transformed himself into an irreconcilable tool, and at the time when my mom would spend hours in the garden, tending her roses and humming tunes from Mary Poppins in an authentic English accent.

On my first day of work at Animal Kingdom, I woke up before dawn, showered, shaved, and gelled my freshly shorn hair into place. In time, this would become subconscious ritual, but on this day, it felt exotic, like I was living the life of a real estate broker in suburban Shreveport. The air outside was thick as bacon grease. It clogged my pores and streaked my windows as I raced down I-4.

Before heading to the park, I had to stop at the costume warehouse to pick up my wardrobe. I was certain Disney would stick me in culottes and a gabardine blouse like some old-timey photographer, but the lady behind the counter surprised me with khaki shorts, a khaki, short-sleeved button-down, and a safari hat. I looked like Banana Republic circa 1986, but I was stoked. I immediately started planning ways to mod my outfit with personal touches—a Buzzcocks patch safety-pinned to the shoulder, a Warhol image stenciled on the shorts, a few well-chosen ska buttons on the crown of the hat.

The ink was still wet on my time card when Orville cornered me. “I appreciate that you’re making an attempt to personalize your wardrobe, but there are a few details here that just won’t wash. First of all, tuck in your shirt.”

I made a plea for fashion. “Don’t you think that’s just a little too neo-Con? Nothing says ‘my mommy dresses me’ like a tucked-in shirt.”

“Don’t you think I’d come to work in sweats and Genie slippers if Disney allowed it? Second of all, shoelaces must be tied—don’t even try to argue that one. And for Pete’s Dragon’s sake, tighten your belt. Nametag goes on the left side of your shirt. You have to take off no less than one of those thumb rings. Lose the chain wallet and put away the sunglasses. Guests need to be able to see your eyes.”

I made the wardrobe modifications, and presented myself to Orville, who eyed me like he was sizing up a potential avalanche chute. He ran an exasperated hand down his face. “It’s not even nine yet.”

The photo lab was already humming with activity. Photographers in khaki uniforms streaked in, dumped canisters of film into the development machine, and ransacked a pile of camera parts before rushing back through the doors. Orville wasn’t kidding about the skill level of these amateur shooters; they handled lenses the way toddlers handle kittens, and Orville watched them in periphery, his dry lips drawn tight against his teeth, his fingers skipping across the debossed letters on his nametag every time a lithium battery cracked against the linoleum floor.

I reached for one of the cameras on the countertop. “Nikon, huh? I’m a Canon man myself, but I suppose I can work with this.”

Orville held up a pudgy hand. “Not so fast, White Rabbit. You may look the part of a Disney Cast Member, but you have a lot to learn before I can send you out on your own. Put that camera down and follow me.” He opened the door and bowed grandly. “It’s showtime!”

I stepped through the door of the drab photo lab and into another world. Everywhere I looked, there were brilliant colors and flashing lights. Huge dinosaur skeletons and roller coasters filled with rapturous, screaming children, grinning like newlyweds on Día de Los Muertos. Vendors were in mouse ears selling mouse-shaped toys and mouse-shaped ice creams. There was music everywhere, indistinct theme songs that quickly faded into the auditory topography, and the stench of sodium and high-fructose corn syrup.

It was like crossing the border from some undeveloped country of impoverished manufacturers into an empire of sensational hedonism. Despair didn’t exist here. Neither did gloom or desperation or sad endings. Inside the impenetrable fortress of Disney World, fairies, genies, and mermaids were real; parking tickets, dead batteries, and blurry photographs were make believe.

It was my first time “onstage” as a Disney Cast Member, and it was thrilling. In my mind, I had just snuck into Disney World through an open back door, and now I was free to do whatever I wanted—so many gleaming handrails, so many clean surfaces. The smooth pathways banked through the vegetation, disappearing seductively beyond my reach every time I rounded a fresh corner. My shadow tugged at my heels, yearning to be set free with a pair of skates and a spray can. Orville was quick to remind me that I wasn’t there to indulge my fantasies.

“There are thousands of details that set the Disney parks apart from other theme parks.” His deep baritone suggested he was presenting a well-rehearsed speech in front of an amphitheater of new Cast Members. “Naturally, Disney properties are well tended, their communities virtually crime free, and their roads unblemished by potholes, but these details would be wasted effort without the cheerful smiles of the Disney staff.” To demonstrate what he meant, he twisted his face into a stupendous jack-o’-lantern grin. “Now you.”

I jerked the corners of my mouth upward the way I do when somebody points a camera my way. Orville’s face dropped.

“Let’s try something else,” he said. “Pretend you’re standing in front of a jury, trying to convince them you’re not a sociopath….”

Nothing was ever so bad in my life that Disney couldn’t make it better: a skinned knee, a Little League losing streak. For small things, a simple Disney movie might have been enough. For bigger problems, it took a trip to Disneyland.

This was LA in the 1970s. The new Mickey Mouse Club dominated the after-school airwaves. Bedknobs and Broomsticks picked up an Academy Award for best special effects. Herbie the Love Bug was on a roll, and The Apple Dumpling Gang and The Witch Mountain series were the talk of the blacktop. All across America, every Sunday night, entire families fell silent as “When You Wish Upon a Star” signaled the opening credits of The Wonderful World of Disney.

For a six-year-old kid, Disneyland was the greatest place on Earth, a destination that was reserved for the most extraordinary of special occasions. Birthday parties qualified. So did Christmas and graduation ceremonies. Of course, I wanted to go to the park every day. I wanted to live at Disneyland. Every moment away from my parents was spent conspiring to escape bedtime and vegetables and all the other shackles of childhood regulation so that I could live out my days in wonderland.

I fantasized about inhabiting the Pirates of the Caribbean ride, that had those raucous bazaar scenes with the bawdy wenches and filthy, leering drunkards and the menacing skeletons draped over piles of glittering treasure. I would have given anything to step off the boat and disappear on one of those white-sand islands. To live among the fire-ravaged villages of the Caribbean of my dreams.

But that wasn’t all. I wanted to be a part of the Small World ride too. And Mr. Toad’s Wild Ride. Tom Sawyer’s Island was a preternatural paradise to me, a place where parents never assigned chores and the pontoon bridge replaced homework as life’s most challenging obstacle. And that huge wonderful tree house where the Swiss Family Robinson spent their days—I could haunt those branches for hours, transfixed by the sheer ingenuity of a canopied bed or a table made from a tree stump and a supply of water that was pulled from a crude but brilliant coconut husk conveyor.

Leaving the park was impossible. I was that kid in the tram throwing a tantrum all the way through the parking lot, grabbing light posts and car door handles and anything I could get my candy-coated fingers around. My life was at its best right there in Tommorowland.

My father, a sensible man, was an electrical engineer who owned his own computer business. My mother wrote allegorical children’s stories about colorful witches. They met during World War II and built their lives in the postwar boom of mid-century America. They used words like “preposterous” and “swingin’” and laughed out loud at the wholesome comedy of The Lawrence Welk Show. Already in their autumn years when I was born, they were looking forward to my father’s retirement, less than a decade away.

And so it happened, following a gripping spelling bee victory hinging around the word “flotsam,” that I found myself awake at sunrise on a Saturday, turning on lights and banging pots and otherwise helping my parents wake up so that we could get to the park for a hard-won celebration. The trip from my front door to Disney’s parking booth took forty-five minutes, but it felt like hours. We arrived before the park even opened.

While my dad paid for the tickets, my mother pulled aside one of the Disney staff stationed near the turnstile and whispered a few words in her ear. She smiled and nodded, then leaned down close to my face and whispered, “We have a special honor for boys who win spelling bees. How would you like to be the first one in the park?” My mom gave me a collaborative wink.

I couldn’t believe my luck. I was to be allowed inside the gates of the Magic Kingdom before the park even opened. I had somehow found a loophole in the restrictive legislature of child management, and I was determined not to waste my opportunity. Once and for all, I was going to learn the answer to those age-old questions: Where did Mickey and his friends go when they weren’t signing autographs or appearing in parades? What did they do when no one was looking?

I stood behind the velvet rope at the bottom of Main Street and imagined I could see Minnie pulling open the curtains of the chocolate shop and Goofy polishing the railings of the Magic Castle. When they drew back the rope and let me go, I broke free of my dad’s grasp and ran as fast as I could through the winding streets of Fantasyland, confident that I would find things that no kid before me had ever discovered. By the time my parents caught up with me, two hours later in the Missing Children Office, I was exhausted and elated.

That little peek behind the Disney curtain was a religious epiphany. For the first time, I saw something more than just rides and candy and cartoon characters. I saw a lifestyle of happiness and support, a group of people who cared for parents and lost kids they had never even met just because they were sharing the Disney Dream.

“Freeze!” Orville snapped. “That’s your Disney smile right there!”

I studied my face in a Tinker Bell mirror hanging in a souvenir kiosk and tried to memorize the feeling, but Orville was already beginning his tour of Disney’s Animal Kingdom. There was a section loosely themed around Asia, and one like Africa. The place where we had started was Dinoland, and we finished in an area called Camp Minnie-Mickey, where, Orville explained, I would be spending most of my time behind the lens.

Each land was a neighborhood with its own distinct music, smells, and entertainment. Africa had dense vegetation and tribal drums, indigenous dancers performing subdued erotic movements, and charred meat on skewers. Dinoland was stripped down to look like an archeological dig inexplicably located in a carnival midway. There was nothing surprising about the layout—a Queen’s necklace where each land was a crown jewel surrounding the park icon, which in this case was a large artificial tree called The Tree of Life, carved with hundreds of animal images and decorated with thousands of plastic leaves that shivered in the morning breeze. In each section, Cast Members wore costumes that defined their role: embroidered polyester in Asia, dashikis in Africa. Kiosk vendors wore shirts patterned with Rorschach designs and souvenir salespeople wore solids. Every Cast Member played for a team within the Disney franchise, and you could sort the teams by the color of their jerseys.

As we walked the park, Orville lectured me on the Rules of Disney. “When you’re in an area with Disney guests, you must make yourself a part of their Magical Experience.” Seeing my confusion, he heaved an aggrieved sigh. “You didn’t read any of the literature, did you? Don’t answer that; you’ll spoil whatever Magic I have left today. Listen closely. Cast Members should always keep in mind the following seven Guest Service Guidelines: (1) Make eye contact and smile at each and every guest who enters the park; (2) greet and welcome each guest as they approach; (3) stop and offer assistance even if nobody is asking for it; (4) if you sense that a guest is having a less than Magical moment—are you listening to me?”

“If I sense that a guest is having a less-than-Magical moment.” Parroting back the last five seconds of a boring lecture was a skill I had developed around the second month of kindergarten.

Orville sniffed and continued, “If you sense that a guest is having a less-than-Magical moment, provide immediate recovery any way you can; (5) project the appropriate body language on stage at all times; (6) preserve the Magical Experience; and (7) as she or he is leaving the park, thank each guest and invite her or him to return soon.”

“Guest Service Guidelines,” I repeated, staring at a beautiful girl dressed in a Pocahontas costume, posing for pictures with a group of children. “Got it.”

Orville inserted his own considerable frame between the Native American Princess and me. “Let’s try a simple exercise. You see those two Japanese women standing there looking at an upside-down map of Universal Studios?”

“Yes.”

“Go ask them if they need help.”

Some insipid Phil Collins song was trickling out of the vegetation—“Something, something, my heart.” It combined the hopeful evangelism of gospel with all the soulful depth of a high school musical.* I moved cautiously to the side of the two women, trying to recreate my Disney smile from before. The women were in an advanced state of flustered, talking very fast in Japanese and tugging at the soggy map, like grommets fighting over a bong.

“Excuse me,” I enunciated. “Can I help you?”

The women looked relieved to see somebody with a nametag. “Toilet?” said one.

“No problem,” I said. Remembering one I had just seen, I jerked my thumb over my shoulder. “One hundred yards. On the right.”

“Thank you,” they chirped together, and ran off.

“Say-o-na-ra!” I said in my best Japanese, then beamed as Orville joined me. “Ta-da!”

“That,” he said, “was terrible. Stage presence is of the utmost importance. When onstage, a Cast Member should always display appropriate body language. This means, stand up straight. Don’t lean or sit or cross your arms. Keep your hands off your hips and make eye contact with the guest at all times. A Walt Disney World Cast Member never points with a single finger—and he never uses a thumb.* Instead, use two fingers.” Orville held out his index and middle fingers together. “Or, to be on the safe side, the whole hand in the style of a karate chop.”

Just then, a cheer erupted from the crowd, and Mickey Mouse appeared. He was smiling his big grin and walking with that classic Steamboat Willie swagger. Instead of his traditional primary-colored overalls, he was wearing a khaki safari outfit with an outback hat and scout patches on the sleeves. Everywhere he turned, people were adoring him as if he were the Second Coming.

“Is that one of the Mickeys I’ll be shooting?” I asked.

The color drained from Orville’s face, and he gave his forehead a vaudeville slap. “Oh my stars and garters!” he gasped. “When referring to a character such as Mickey or Minnie, keep in mind that each one is a unique individual and, as such, must not be referred to in the plural.”

I watched the one and only Mickey Mouse disappear behind a Cast Members Only door, then reappear a few seconds later, looking mightily refreshed and maybe a little taller. “Aha!” I pointed with two fingers. “How do you explain that?”

“Each performer can only last so long in their costume in this heat,” Orville said. “So when we make the exchange, you have to come up with a plausible reason why each character disappears for a spell.”

“Like he’s got a phone call?” I ventured.

“Absolutely not,” Orville said. “A Cast Member should never let on that one of the characters is doing something ‘out of character.’ When Tigger leaves the autograph line every thirty minutes, he isn’t taking a Powerade break; he is going to the Hundred Acre Wood for bouncing practice. Brer Fox is checking the briar patch, etcetera.”

“So maybe Mickey got a phone call…from his Hollywood agent who just cast him in a provocative but tasteful new movie with leading lady Jessica Rabbit.”

Orville frowned at me. “I think it’s better if you don’t say anything at all. Come on, I’ll show you the backstage commissary.”

I began to imagine Disney World as a kind of friendly monarchy, something along the lines of Monaco or the United Arab Emirates, with its opulent kingdoms built around shimmering resort hotels, or like a religion. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints has strict appearance guidelines, as do Jehovah’s Witnesses and pretty much all sects of Islam. A Cast Member who peppers his speech with smiling courtesies doesn’t think about that choice any more than a Muslim thinks to praise Allah throughout his daily conversations. Wearing a conservative hairstyle is no more taxing than the Orthodox Jewish custom of wearing side curls.

I was half paying attention to Orville’s monologue as we entered the cafeteria and got in line, so I didn’t really notice the beautiful Pocahontas until I bumped into her, nearly knocking over her Diet Coke.

“Double-u, tee, fuck,” she growled.

“Sorry about that,” I said. Instead of her yellow Indian princess dress, she had on an Adidas tracksuit, and her long, dark hair was tied up in a bun, but it was definitely the same girl I had seen in the park, smiling and signing autographs. She had the body of a dancer, athletic and elegant, and a regal jawline. Her face was done in thick makeup, rouged cheeks with long, dark eyelashes. She had eyes like my ex, fickle globes that changed color with every mood swing. She didn’t say anything, so I added, “First day. I’m a little clumsy here in the Church of Disney.”

“Excuse me?” Her lip curled when she said this.

“Well, not literally. I mean. You have to admit it’s sort of a religious experience, right? These outfits. The characters. All deities in the Disney pantheon, and Walt’s Papa Zeus.” Pocahontas’s face was blank. “It’s Disneyism,” I babbled, now committed to my theme, “and Orlando is the Holy Land.” I felt off balance. I was suddenly very conscious of my short hair and vintage Banana Republic wardrobe.

“You don’t know what you’re talking about,” Pocahontas growled, her now gray eyes churning like storm clouds. “Disney is about family values. Not religion.”

I was flexing my arms, biting my cheeks, letting myself get riled up the way I swore I wouldn’t if I ever found myself face to face with my ex-best friend. “Kids eat Mouse burgers like they’re taking Holy Communion, learning the Gospel of Walt: ‘Tigger is real.’ ‘There’s only one Mickey.’ You deceive children into believing you’re a Native American princess. What kind of values are you teaching these kids?”

The flush rose from her tan chest, up her neck, and into her cheeks where it glowed like hot coals through the heavy stage makeup. She looked me up and down with unconcealed contempt. “Let me explain something to you, photographer.” She spat the word as if it was a bug that had flown into her mouth. “Piaget stated—and I believe—that the unconscious, or semiconscious characteristics of imagination must be stimulated early and often in a child’s development to ensure proper cognitive development as an adult. What we do as Cast Members aids in the development of a healthy, productive society.” She went on like this for a while, spouting social theories that echoed sociology lectures I hadn’t paid attention to in college and couldn’t understand now. I was acutely aware of other Cast Members in the commissary watching or pretending not to watch, entertained by my abject humiliation. Eventually, the tirade stopped and it was my turn. Orville was smiling as he turned his gaze on me.

“Children are idiots,” I countered.

Pocahontas stormed off. I paid for my lunch and found a seat at one of the long tables. Five minutes later, Orville was still smiling at me over the top of his sandwich.

“That didn’t go the way I expected,” I said.

“It went pretty much exactly the way I expected,” Orville said.

“She took it so personally.”

“There’s something you have to understand about your fellow Cast Members,” he said, and I knew he was about to say something serious because I could clearly count his chins. One two three. “Disney World employs forty thousand people from all corners of the globe. They come to Orlando and work for minimum wage, and they don’t care about the money. They work here because Disney makes them feel something: nostalgia, pride, love…Whatever it is, it’s real, and it keeps them here for their entire lives.” He pushed his plate away from him. “Cynical journalist types, on the other hand, don’t last long here.”

“You think I’m a troublemaker.”

“If I thought you were real trouble, I wouldn’t have hired you. We have a state-of-the-art security system with cameras, uniformed guards, and undercover ‘foxes’ who are trained to take you down long before you become a problem.” He pushed his spectacles up on his nose and winked. “But I know that won’t be necessary with you. I can see your momma taught you well.”

His words summoned memories of my mother. I tried to picture her as she was when I was eight: vital, energetic, laughing at my ridiculous Baloo impressions, a spatula in her hand, a smear of cake frosting across her cheek. But the old images were flimsy, and easily replaced by modern apparitions of my mother struggling to walk from the bed to the dresser, trying unsuccessfully to keep food down, and fighting a juggernaut of pain just to fill her lungs with air. Was anyone with her now? Would anyone be at her bedside when she slipped away? My fingertips traced the soft skin around the base of my thumb where the ring used to sit. The shadow beneath my hand was formless and weak behind the tinted glass of the commissary. I struggled to convince myself that I wasn’t listing to the side, that this feeling of vertigo was in my imagination.

Orville was staring at me as if it was my turn to do something. I could hear the echo of his lecture, but I had lost the thread entirely. “Don’t you want to know what happens if you break the Rules at Disney?” he said with a gravedigger’s sobriety.

My mouth was dry, so I just nodded.

He cleared his throat. “Punishments for disobeying the Rules are handled immediately. For most offenses, we have a system of ‘reprimands,’ whereby a Cast Member may accrue five points within any twelve-month period before being let go. Reprimands range from one point for a wardrobe violation to two points for unauthorized food tasting.”

“Food tasting?”

Orville sighed. “No eating onstage, remember?”

“So that’s it? No matter what I do, I get a slap on the wrist?”

“I’m not finished,” Orville wiped the corner of his mouth on a napkin before delivering Disney’s three supreme evils. “Number one: using, being in possession of, or being under the influence of, narcotics, drugs, or hallucinatory agents during working hours or reporting for work under such conditions. Number two: conviction, plea of guilty, plea of no contest, or acceptance of pretrial diversion to a felony or serious misdemeanor, such as but not limited to child abuse, lewd and lascivious behavior, or sale/distribution of controlled substances. And number three: violation of operating rules and procedures that may result in damage to Company property. Any Cast Member caught with a hand in one of those cookie jars would be terminated immediately.

“Termination,” he continued, “isn’t always a simple matter of being let go from Disney. If a Cast Member gets fired from the Kingdom, there’s a chance she or he may never be allowed to visit the park again. Disney reserves the right to prosecute that person to the full extent of the law as a trespasser. In other words, you could be banished from Eden.”

I’ve never been a fan of team sports—the sweaty male bonding, the common goal of victory over another group in different color jerseys, or the locker rooms. Which is not to say I didn’t try: Little League, AYSO, flag football, Red Rover. I participated in everything, dutifully lining up on one desiccated field after another with a bunch of kids in the same color shirt. That’s what I hated first about team activities—the ridiculous costumes that defined the tribes. But I quickly learned to despise the Rules of the Game even more. That was what first attracted me to skating: the total lack of structure meant I could participate any way I wanted. From the moment I got out of bed, I could be on my skates: out the front door and down the steps, up the driveway and onto the street. When the street got boring, I could move to the sidewalk with its never-ending obstacle course of pedestrians and baby strollers and dog shit. I made my own Rules. I wore my own uniform. It was the same feeling with surfing and skiing and later snowboarding—activities that empowered a person to blaze a unique trail through a constantly evolving landscape.

When I graduated high school, my brother Michael gave me a copy of Ayn Rand’s Atlas Shrugged. It was like a fuel dump beneath my teenage bonfire. Here, at last, was adult justification for my rebellious angst, an ethos that celebrated my individuality as a philosophical given (as opposed to organized religion that subjugated the individual impulses using tools like sing-alongs and vigils and, yes, even costumes). Atlas Shrugged, in general, and John Galt, in particular, was all the justification I needed to devote my life to the one thing I truly cared about: skating.

This decision was not popular with my father, a principled man of sensibility and reason who grew up during the Depression. But my mom made a successful appeal on my behalf to allow me to pursue my dream with the compromise that it would not disrupt my education. By my sophomore year in college, I had my first skate sponsor. By the time I could legally drink in the States, I had traveled to sixteen different countries on four continents as a pro rider.

My first tag was GALT. I’d paint it on walls in every city I visited, customized with a Celtic T and four circles that represented the wheels beneath my feet. I was fiercely loyal to the principles of individuality, vigilant against the comforts of polite society and anything that could be summed up with “-ism.” When I was twenty-two, I bought my first camera and started a skate zine. This was back when print was still relevant, and it thrilled me to get letters from places I’d never heard of, to know that there was a global community of individuals devoted to the same principles I advocated. I imagined a secret society just like the one in Atlas Shrugged, made up of people who eschewed the Rules in favor of something better. This invisible web of independent thinkers replaced the Disney Dream as my idealistic vision of the future.

I left the park that day feeling as if I’d just finished cramming for a final exam. What had, at first, seemed like a whole lot of inane regulations was, in fact, a corporate lifestyle that bordered on autocratic fascism. It’s no secret that the most restrictive societies in the world germinate the most vituperative rebellion. The despotic regions of the Middle and Far East produce the choicest heroin; an abnormally high percentage of diagnosed sociopaths have a military history; and everybody knows Catholic schoolgirls are the most mischievous adolescents on the planet.

The Disney Rule Book was a manifesto of totalitarianism, a recipe for deviance as certain as the countdown of a live hand grenade. It was everything I had fought against, all the principles that opposed my John Galt ideal of freethinking and counterculture individuality. But there was something glorious about it too, the genetic code of a seed that had been dormant inside me since my teenage rebellion. Accepting Disney in my heart meant surrendering myself to a beautiful truth that was far more seductive than my philosophy of earnest insurgency. Like the supernatural suck of an undertow or gravity’s insistent tug, I could sense an irresistible comfort in Disney’s unyielding order. The holy spirit of Walt was offering me a big, furry bear hug, and I was rushing to his bosom.