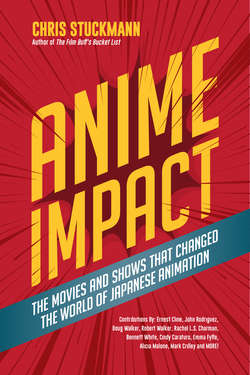

Читать книгу Anime Impact - Chris Stuckmann - Страница 26

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1988 • Akira

— John Rodriguez —

And with these simple words—

“Neo-Tokyo is about to explode!”

—an anime fan is born.

I’d never been to the then-newish Cleveland Cinematheque before and didn’t know that I wanted to go, given its distance from my suburban haunt. But that one-sheet … that was something, huh? Just that boy—I didn’t yet know him as Kaneda—holding that preposterous rifle over a background of black, broken buildings. Who was this badass boy with the grim-set face? Was he this story’s eponymous hero? Those five block letters at his feet—the ones screaming AKIRA in bloody, bullshit-less red—surely suggested so. Would he wind up the harbinger of Neo-Tokyo’s imminent explosion, or perhaps serve as the city’s salvation? Suddenly, a thirty-minute drive into the city seemed less a burden than a necessary fact-finding mission.

And so I learned. I learned of Kaneda and the Capsules, that gang of young misfit motorcyclists. Of Tetsuo, the Capsules’ runt of the litter, chaffing at Kaneda’s smothering protectiveness. Of the espers, the wizened little psychics who presage the dangerous psychic powers growing within Tetsuo, and of Colonel Shikishima, the espers’ custodian and the hard case plotting to assassinate a boy in order to save a city. And, of course, of Akira, the doom and/or salvation buried under Neo-Tokyo’s Olympic Stadium.

Akira certainly wasn’t the first anime to leave a cultural footprint on America—those of us raised on Robotech, that bastard spawn of three unrelated series, know that well. Yet Akira was undoubtedly the tipping point, the keystone for myriad western anime fandom. So the question becomes: Why? Why this film, which didn’t even receive US distribution until eighteen months after its release in Japan?

Let’s start by looking at the competition. That trip of mine to the Cleveland Cinematheque took place during the summer of 1990. What kind of sci-fi fare could I have enjoyed had I chosen to stick closer to home? Well, Total Recall had just hit theaters. If that wasn’t my thing, I could have hitched my train to the final Back to the Future sequel. And hey, Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles was still karate-chopping its way to a $202 million worldwide gross in the local second-run theater. Cowabunga!

Is this to suggest that Akira’s western success is owed to a lack of viable competition? “Hardly,” says this Total Recall apologist. But while I enjoyed getting my ass to Mars as much as the next guy, I’d never hail Total Recall as heady cinema. Same goes for Back to the Future III and Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles: You can argue they’re fun, but you can’t argue they’re thinkers. If you think I’m cherry-picking, I invite you to scan down the list of 1990s top-grossing films. Spoiler alert: They don’t get any brainier.

Where, then, is the burgeoning intellectual science fiction fan to turn?

Enter Akira. Here’s a film with something to say! You take one look at Neo-Tokyo—that crowding vertical skyline, that sea of pinprick lights, each one a window on some anonymous life—and instantly understand why Kaneda and his Capsules simply must stake their claim to their scanty strip of street. Youth cries to be noticed. It rages against the notion that it must ultimately be consumed, must become one of “The Many” who shuffle through their daily routine, fuel for the machine. Kaneda’s Capsules call bullshit on that demand. And though we watch their little rebellion from cinema screens or televisions 7,000 miles away from their fictional exploits, we disillusioned young raise a cheer.

Then there’s Tetsuo. The boy with all the gifts, Tetsuo’s bubbling cauldron of rage and resentment is instantly recognizable to any teen. True, what’s fighting to burst from most teens is different than what Tetsuo’s bottling—not psychic energy but rather social angst and sexual frustration—but the principle remains the same. Of course, Tetsuo’s powers destroy him in the end, not to mention his girlfriend (R.I.P., Kaori: we hardly knew ye) and a goodly chunk of Neo-Tokyo. So, perhaps Akira can be read as a parable on the need for youth to reign itself in. Yet Tetsuo also transcends to something greater: a whole universe born of his personal Big Bang. Tetsuo the boy dies; Tetsuo the legend will live on until the last star in his new universe goes dark. That, friends, is a legacy. Who wouldn’t want that?

And though Akira is often dark in the extreme, there’s a fundamentally hopeful sentiment here. Akira’s old Tokyo wasn’t much to write home about before being leveled by the explosion that triggered World War III. Yet the city that rose from the rubble became more prosperous in just thirty years than its predecessor had ever been. Tetsuo couldn’t contain his powers—he literally burst apart at the seams. Yet during the film’s climax, the espers intone that Tetsuo’s evolution represent humanity’s future. This isn’t some nihilistic prophecy: it’s a suggestion that we as a species are growing, that through our strife and our selfishness—perhaps because of it, indeed—we stand on the precipice of Great Things.

There’s been a lot of hand-wringing over the notion of a westernized Akira, and that’s understandable. Akira is in many ways intrinsically tied to its roots—note in particular the notion of “rebuilding after the bomb,” a gargantuan task the Japanese understand all too well—and some of those root themes aren’t going to translate. Still, Akira speaks to people of all cultures. You could watch this film in Big Sky, Montana with nary a skyscraper in sight (the Rockies excepted) and still come away thinking: If only I had Kaneda’s bike. If only I had Tetsuo’s powers. What could I do? What could I be?

Coming back around to the original question—“Why Akira?”—is it simply the appeal of wish fulfillment? Maybe in part, but not wholly, I think. Because Akira also subverts wish fulfillment. It says, “Sure, you can have super powers, kid, but don’t get cocky, cause you’re only gonna end up squishing your girlfriend into pink goo.” (R.I.P., Kaori: that really was a lovely skirt.) Maybe that’s part of Akira’s appeal, too. It’s honest enough to admit that being The One isn’t all black leather and bullet time. It means pain. It means responsibility and consequence. That’s right, teens of today: there’s no escaping the fact.

But it doesn’t necessarily mean compromise of identity. Later in life, you’ll still be you. And if “you” ends up a disembodied universe, that just means you’re gonna live forever, kid. Not a bad way to go.

John Rodriguez is a personal trainer whose devotion to physical fitness is exceeded only by his fervor for all things film and literature. John is currently finishing his first novel—a fantasy that’s sparked fantasies of a challenging new career.