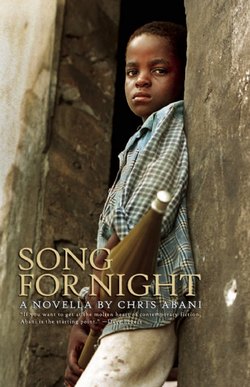

Читать книгу Song for Night - Chris Abani - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеMemory Is a Pattern Cut into an Arm

I wake up confused. It is dark and I have to remind myself it is still the same night. As soon as I can, I should make some kind of calendar. The branches I am sleeping in are safe but uncomfortable. I can’t place the sound that has woken me at first, but there it is again: the soft put-put of a motor. Carefully I look through the net of leaves and see a small motorboat gliding past. There are several men sitting in it, all heavily armed. One is in the prow operating a small searchlight that is sweeping the banks. They are all smoking, and from the smell of the tobacco I can tell it is top-grade weed. I inhale deeply, cautious not to make any noise. God I could use some of that weed; my head is pounding. It is an enemy vessel; but it could just as easily have been taken over by one of us rebels. Although, since the men in the boat are searching for anyone hiding in the water or the thick grass on the shore, it is unlikely. Not because we are not capable of it, but because this was most recently rebel territory and we wouldn’t be killing our own, and murder is clearly the intent of the search. Unsettled, I rub my arm as I watch the boat circle under me then move on. It only lasts for a few moments but it feels longer.

As they depart, I reach for my knife. If Nebu had survived the explosion—which was unlikely since he was standing right over the mine when it went off, and so took the full blast—he couldn’t get far, wounded as he must be. Without a doubt the patrol I have just seen will find him and finish him off. With my knife tip I cut a small cross into my arm for Nebu, wincing as the blood blisters up. I reach behind me and cut into the tree and collect sap with the knife tip and smear it into the small cut. It should help with the healing, I think, but almost immediately it starts to burn and I know this is not a good thing, so I take out my prick and piss all over my arm, feeling it stinging and cooling at the same time. In basic first aid they told us that human urine is the best field disinfectant there is. Holding my arm out, I let it dry in the slight breeze. I reach for a cigarette and light it. I am high enough that the men in the boat won’t notice, even if they come back.

In the dim glow from the cigarette, the crosses on my arm look exactly like what they are: my own personal cemetery. I touch each cross, one for every loved one lost in this war, although there are a couple from before the war. I cut the first one when my grandfather died; the second I cut when my father died, with one of his circumcision knives. My father the imam and circumciser who it was said betrayed his people by becoming a Muslim cleric and moving north to minister; and all this before the hate began. The third I cut for my mother who died at the beginning of the troubles that led to the war. The rest I have cut during the war: friends, comrades-in-arms. With the one I just cut for Nebu, there are twenty in total. Eighteen are friends or relatives, as I said, but two were strangers. One was for the seven-year-old girl I shot by accident, the other for the baby whose head haunts my dreams.

I turn over my right forearm. There are six X’s carved there: one for each person that I enjoyed killing. I rub them: my uncle who became my step-father, the old women I saw eating the baby, and John Wayne, the officer who enlisted and trained us and supervised our throat-cutting and our first three months in the field, the man who was determined to turn us into animals—until I shot him.

“I shot the sheriff,” I mumble under my breath, mentally walking through my memories, examining each one like a stranger walking through my own home, handling all the unrecognizable yet familiar objects.

It was a Wednesday. How I remember that detail is unclear given that nearly all my memories are mixed up, as though I have taken a fall and jumbled the images: probably a result of concussion brought on by the explosion. Wednesday, late afternoon: and the sky heavy with dark clouds. The muted light that fell like a hush was darkened by the deep green of foliage to one side, the red unpaved road scarring the middle, and to the other side a clearing covered with the gleam of white gravel and a church, not much more than a low whitewashed bungalow with a cross atop its corrugated iron roof, half of which had collapsed—maybe from a shell or a mortar, it was hard to tell. Another bungalow, the priest’s house, was off to the back, set close to the encroaching greenery. In the front of the church was a battered pickup truck that was idling in the shade of a tree. A white priest, neck and face red against his white soutane, sat in the cab. In the shadow of the bombed-out church, two women were washing a statue of the Virgin with all the tenderness of a mother washing a child. A seven-year-old girl played in the gravel by their feet. I stared at that sight unbelievingly. Of all the things they could have salvaged, I remember thinking. Just then, a man came round the corner carrying a statue of Jesus, cradled like a baby. I fought tears. There was something matter-of-fact about it all that was heartbreaking.

John Wayne stopped us with a casual wave, and we spread out wordlessly into the formation we had been trained to. The people in the church tableau froze as we approached: the man holding Jesus, the women washing the Virgin, and the priest in the truck whom I assume meant to carry the statues to another church or parish where they would be safe. As we moved forward in a loose fan that tapered into a point, with John Wayne leading, only the child moved. Smiling, she ran toward us. John Wayne bent down, arms spread, a father home from work, except he didn’t look like a father, more like a bird of prey. He picked up the seven-year-old girl and held her to his side. Something about him in that moment must have terrified her though because she began to cry.

“What is your name?” he asked her.

“Faith,” she said, still crying.

John Wayne touched her face tenderly, and then when she smiled tentatively through her tears, he threw his head back and laughed.

“This one is ripe. I will enjoy her,” he said, looking right at me, as though he expected me to challenge him, like I did the first time he had forced me at gunpoint to rape someone, but whatever he saw in my eyes made him laugh even louder. Without thinking, I lifted my AK-47 and opened fire. He moved, instinctively I think, the way an animal will, to escape the shot, and the bullet went through the seven-year-old and found John Wayne’s heart. They both looked at me, faces wide with shock for a long moment, then John Wayne fell, taking the girl with him. Everyone scattered for cover, the women, the man carrying Jesus, still carrying Jesus, and the rest of the platoon; everyone except Ijeoma, who stood behind me, and the priest, who leapt out of his car and ran toward John Wayne and the girl.

Without a word the priest bent down, said a prayer over the child, kissed her forehead, and drew a cross in the air above her with two fingers. He pried her from John Wayne’s arms and held her to his chest, her blood staining his white soutane. He seemed confused, unsure what to do next, and his eyes locked on mine were filled with tears and an expression I have seen too many times. He opened his mouth to speak but nothing came out. I was numb to John Wayne’s death. Gladness would come later. For now, all I could think was that the only real casualty was Faith.

I became aware that Ijeoma was rubbing my back gently. Without a word I turned and put my head on her shoulder. When I looked up, the rest of the platoon was gathered in a circle around us. Nebu had unpinned John Wayne’s rank insignia and was holding it in his hand like a burning coal. He approached me silently and pinned it to my shirt, saluted, and turned around. The rest of the platoon came to full attention and saluted. I was now the leader, months into the war; our war.