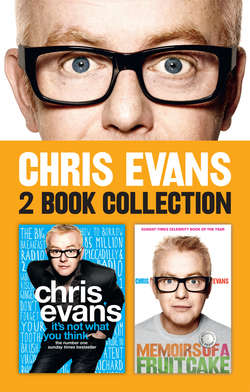

Читать книгу It’s Not What You Think and Memoirs of a Fruitcake 2-in-1 Collection - Chris Evans - Страница 13

Top 10 Basic Facts about Christopher Evans

Оглавление10 Born 1 April 1966

9 In Warrington in the north-west of England

8 Mother Minnie (nurse)

7 Father Martin (wages clerk, former bookie)

6 Brother David (twelve years older—nursing professional)

5 Sister Diane (four years older—teaching professional)

4 Very bright

3 Reluctant student

2 Needed glasses but nobody knew for the first seven years of his life, which meant I couldn’t see a bloody thing at school (presuming this is what the world actually looked like)

1 Had fantastically red hair

Life for me growing up was no great shakes one way or the other. We were an average working-class family with an average working-class life. We weren’t poor but, looking back, we were much less well off than I had realised.

I was nought to start off with, but I quickly began to age and lived with my loving mum and dad, Minnie and Martin, and my elder brother and sister, David and Diane. Our house at the time was both a home and a business. We had a proper old-fashioned corner shop like the ones you see on the end of a terraced row of houses, just like in Coronation Street, some of which had those over-shiny red bricks that looked more like indoor tiles. This is my first memory of one-upmanship: we never had those bricks but what we did have was a thriving retail outlet. Our shop sold almost everything—at least that’s what my mum says—not like Harrods sell almost everything, like elephants and tigers and miniature Ferraris, but like a general store might sell almost everything, like chickens, shoelaces, cigarettes and liquorice.

I don’t remember the shop at all, to be honest, but I do remember the tin bath that we all shared on a Sunday night in the living room behind where the shop was. It was a heavy, old, silvery grey thing, rusty in parts, which was ceremonially plonked in front of the fire (for heat retention

purposes, I assume) before being filled by hand with scalding-hot water from the kettle boiled on the stove. This was then topped up with cold water via a big white jug, after which we took our turns bathing en famille.

I remember the outside toilet, the coal shed, Mr Simpson the greengrocer, and the rag and bone man—who I was a bit scared of—but if I’m honest that’s just about it, apart from how upset my mum was when the Council made a compulsory purchase, not only on our house and our shop, but on our whole street, not to mention hundreds of other houses around where we lived, to make way for something so instantly forgettable I’ve actually forgotten what it was.

As a result of this compulsory order we were forced to move to council housing and another part of town some three miles away, which for a working-class family was tantamount to emigrating to Australia. Although many years later my brother did emigrate to Australia and he assured me it was not the same at all.

For my part I wanted to break out of the council estate which we were forced to call home and where I was brought up mostly. From day one I felt compelled to escape those grey concrete clouds of depression.

The house we lived in was of no particular design, in fact it was of no particular anything. It was more nothing than something. In short, it was not the product of passion. Council estates don’t do passion, they just do numbers.

The estate I lived on didn’t even do bricks. Huge great slabs of pebble-dashed prison walls had been slotted together in rows of mediocrity as an excuse for housing. Housing for people with more pride in the tip of their little finger than the whole of the town planners’ hearts put together. People like my mum, who had survived the war as a young girl whilst simultaneously being robbed of her youth by having to work in a munitions factory. People like my dad and my uncle who had fought overseas to protect us from other kinds of Nazis.

How dare they ‘home’ these fine people in such an unnecessary hell?

It was waking up to this backdrop of pessimism and injustice every day that made my childhood blood boil. It was like the whole place had been designed to make you want to kill yourself. A curtain of gloom against a drama of doom. I hated the unfairness of it all.

Why did some people, for example, who lived not more than half a mile away, have a detached or semi-detached house that looked like someone may have actually cared about how it turned out? How come they had nice drives and nice cars and a pretty garden at the front and the back?

Not that I begrudged the owners of such places, or rather palaces as they appeared to me, on the contrary—good for them. I just thought things should be the same for my family.

The apathy of it all also drove me crazy. Why did people who lived on these estates all over Great Britain accept this as their lot? Why did mums and dads bother going to work each day to be able to pay the rent for these shitholes? The authorities should have been paying them to live there, with a bonus if they managed to make it all the way through to death.

So there you have it, that’s where my initial drive came from. It wasn’t that I was bullied at school or the early death of my dad, or any of the other predictable psychobabble reasons often wheeled out to explain success. It was purely and simply that I wanted a better life.