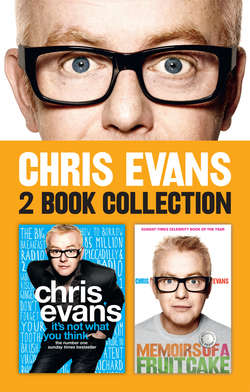

Читать книгу It’s Not What You Think and Memoirs of a Fruitcake 2-in-1 Collection - Chris Evans - Страница 36

Top 10 Things to Consider When Attempting to Make a Move in Your Career

Оглавление10 Make sure you really want it in the first place

9 Really make sure you really want it in the first place

8 Think if it’s going to help you get where you want to be next

7 Think where you want to be ultimately and if it will help get you there

6 Imagine if you had achieved it and how it would affect your life as a result

5 Don’t consider the financial cost, as long as you can afford to carry on living it’s irrelevant

4 Do consider how much of the next few years of your life it will take up and remember you can never get those years back

3 Have an exit strategy—this is so important

2 Never let your nut rule your gut—ever…the brain is not all it’s cracked up to be

1 For goodness’ sake, get out there and go do something about it!

The boss of Piccadilly Radio was a man called Tony Ingham. I phoned up to find out his name and immediately set about composing my note. It was brief and to the point, I explained that I had interviewed Timmy only last night, during the course of which Timmy had let slip that Andy his assistant was leaving, which to me suggested there might be some kind of vacancy coming up and although I would never presume to be able to fill Andy’s role I was willing to do anything for nothing for ever—in fact I think I said I would do ‘everything’ for ever for nothing—if this meant I could work behind the hallowed doors of the great Piccadilly 261.

I sent the letter before lunchtime on the Tuesday and to my amazement and complete and utter joy, I received a reply from Mr Ingham on the Thursday, I went to see him on the Friday and started work on Timmy’s show on the Monday. Incredible but 100 per cent true.

When I went to see Tony he told me Timmy had mentioned the fact that Andy was leaving on purpose because he thought I was quite sparky and had suspected my interview with him was more a fraudulent attempt by me to find out more about working in radio than anything else and that he would soon need a new pair of hands and why not?

Timmy had stopped short, however, of encouraging me further to see if I would do anything about it myself and now because I had, the door was open. However, the rest from here on in was up to me—and by the way I would be expected to do everything for nothing for ever!

My long working days were about to get even longer. I would start at the newsagents at the usual time, go home in the day, return in the afternoon and then, after locking up, hot foot it off to Manchester up the M62 to do ‘whatever Timmy wanted’.

This started by answering the studio phones, a true baptism of fire. Answering Timmy’s phones was like being a stock market trader at the moment a crash happened but for every minute of every show. He would announce a competition over the beginning of a three-minute record, give out the phone number and expect a correct, fully prepped and rehearsed caller before the end of it. If the caller turned out to be below par you’d better not have been the person to put them through.

To Timmy, the callers were everything and the calibre of kids we put on the air told the other kids who was listening to the show—i.e. only great kids were welcome; as in many things, perception was everything. The kids also had to be spread out evenly from a geographical point of view, an equal number of boys and girls was also a target, although more girls than boys was acceptable as long as it was never the other way round.

I wasn’t Timmy’s only helper—there were six or seven of us, some really sharp little operators, smart smart kids, good energy, lots of ideas and bags of confidence. There was Sally and Hannah and Geraldine and Paul and another Chris; they were mostly posher than me but that didn’t seem to matter. They couldn’t have been more welcoming, there was no air of internal competition—we were all too petrified of messing up to think about anything else.

To work on Timmy on the Tranny was even more exciting than listening to it. Timmy really was a genius. I still think about watching him work: he was truly insane but for all the right reasons. The pressure he put us under was nothing to the pressure he put himself under every second of every show. He knew exactly what he was doing but everything was always happening so quickly in his head he often didn’t have time to tell the rest of us what it was he wanted us to do. This was a regular cause of frustration for him and blind panic for us—to be honest we were clueless most of the time.

From the second the red light went off and Timmy put on a song there was furious activity to get the next link ready. Every link meant something, every link had some colour, either a joke, a character, a caller or an interview, and every link had a beginning, middle and end—the end being the most important as, if the beginning or middle failed, a good end would always get you out of trouble.

This is just one of the lessons Timmy taught me that I have used on every programme I have ever been involved with to this day.

This golden time was proving to be a master class in broadcasting, an invaluable and unique learning experience available nowhere but right here, right now, but the heat was about to be turned up—the next stage of apprenticeship on Timmy’s show was to be invited ‘on the air’ as a ‘character’.

This was a huge deal and also a make-or-break moment. Helpers only got one or two bites at the on-air character cherry. If they were successful they would become a bit-part player in an award-winning radio show and would become famous in their own right. Listeners would write to them and want to know who they were and what they looked like; they would be asked to do more characters and be given more air time. If they were unsuccessful, however, they would be consigned to the hell of the phone rooms and sending out prizes, probably for ever.

Timmy asked me if he could see me one night after the show.

‘Er, yes hi, well done tonight, I would like you to think about a character for the show, something different, something that you like, ’cos if you like it, the kids’ll like it, something that you can do night in, night out. Anything—it just has to be clever and funny, that’s all.’ He then paused before adding, ‘Oh, and have it ready for tomorrow night. Byeee’ (!) and with that he was off.

See, perfect, why can’t everyone in life be so straight? How much more time would we all have to ourselves if they were? Timmy didn’t want a conversation, he didn’t want to be your friend, but he did want like-minded people to join in his mini radio revolution.

The pressure was on and for me, pressure works: I came up with a character called Nobby N’O’Level.

Nobby had ten N’O’Levels in nothing. He would always ask Timmy a question about an educational fact to which Timmy would be gobsmacked that Nobby didn’t know the answer. Nobby, as a riposte, would then triumphantly announce something that he knew, which of course was also completely wrong. Finally he would mitigate the whole episode by signing off with his catchphrase, ‘Well, what I don’t know…I don’t know.’

Nobby was very Sesame Street and Timmy was taken with him straight away—he could see that the material for the character was fact-based while also being silly enough to be entertaining and sympathetic enough for kids to like. Nobby was a tryer and you had to love him for that.

He was an instant hit and I was on the air.

What I also was, was very tired, very tired indeed, as well as fast becoming a danger to other drivers.

I had begun to stay on after Timmy’s show to work in the studio. Most radio stations have two identical studios with a control room in between. After Timmy went off the air, Cuddly Dave came on from the studio opposite and Timmy’s studio was free for the next three hours. I would spend the next year of my life hanging around and playing with the gear and practising various techniques and ideas until the wee small hours of the next day.

Adrenaline was my friend—it had to be—I would drive home and get in around two o’clock in the morning, still having to get up to open the newspaper shop before five. I remember having to open all the windows in the car and singing all the way home to keep awake. I could tell I was in trouble when I would suddenly stop in the middle of a Beatles chorus for no reason whatsoever—when it all went quiet I knew the next thing that would happen was that I would close my eyes and who knows what after that; I had to keep singing.

Needless to say, when I did get home I had no trouble falling asleep. It’s still the most tired I’ve ever been. I would be panting out of breath as if I’d just sprinted for the bus, purely from the madness of the day. No complaints though, I loved every second of it but something would have to give, and soon.

I was beginning to run on empty.