Читать книгу Redemption Song: The Definitive Biography of Joe Strummer - Chris Salewicz, Chris Salewicz - Страница 9

6

BLUE APPLES 1965–1969

ОглавлениеWhen the two Mellor boys went out to Tehran in the summer of 1965, Johnny came across a Chuck Berry EP that included the great American R’n’B performer’s version of a song that he thought was a Beatles’ original on their For Sale album, released the previous Christmas. ‘I remember putting on Chuck Berry’s “Rock’n’Roll Music” and comparing it to the Beatles and being a bit surprised that they hadn’t written it,’ Joe said. Discovering that both the Beatles and the Rolling Stones spoke openly of their allegiance to American R’n’B, Johnny Mellor, who had just turned thirteen, further investigated Berry’s music when he returned to the UK, also discovering the unique shuffling sound of Bo Diddley. He loved these artists.

After a brief stint back in London, in 1966 Ron was promoted to Second Secretary of Information and despatched to Blantyre, Malawi, in southern Africa, where he and Anna would spend the next two years. In Malawi, Johnny discovered the BBC World Service which kept him in touch with the new big releases. He was also very interested in the local Malawian musicians. A stamp in his passport also shows a visit to Rhodesia. ‘Ron and Anna quite liked Malawi,’ said Jessie. ‘But then independence came and they came back to England, pretty much for good. They used to say that Johnny had really liked Malawi. But David found it somehow troubling and unsettling.’

In memories of Johnny Mellor at CLFS an etiolated, almost spectral figure stands off to one side, indistinct, passive and vague. It is David Mellor, Johnny’s older brother. At CLFS the younger Mellor boy spent little time with his elder sibling. Later, according to Gaby Salter, he had regrets over this. But no one really seems to have any sense at all of David Mellor, even those who shared living accommodation with him. ‘Although we were in the same boarding house for two years, we hardly spoke at all,’ admitted David Bardsley. ‘Dave Mellor was very quiet, very shy, very introverted – the complete opposite to John. I suspect David was put upon by the world in general.’ ‘David was in my elder brother’s year,’ Andy Ward told me. ‘He was floppy-fringed and quiet, although he wasn’t someone who was bullied. But no one remembers much about him.’

In the cloistered bowels of the British Museum, where he now works as a clock conserver, Paul Buck produces a photograph of David Mellor; my heart leaps as he hands it to me, as though I have made a great find. But the teenage boy in the photograph seems shrouded in gloom and so indistinct as to be almost transparent; his image is so imprecise that he looks like a ghost, or at least a man who isn’t there. My elation vanishes and instead a chill runs through me. In a set of five photographs of the Mellors at Court Farm Road in 1965, the mystery is repeated: in three of them, taken as the family work in the back garden, David is turned away from the camera – all you see is an anonymous back. In the one picture of the two boys with Anna and Ron, Johnny squats between his parents, while David stands, leaning off to one side of Anna. In the printing process a tiny blue smudge has appeared in his right eye, like a tear, a portent.

‘I do have to agree with what most people say about David Mellor,’ considered Adrian Greaves. ‘I didn’t talk to him much at first. He was a nice chap, but you had to initiate the conversation. He seemed very calm but very shy.’ They both read the works of Cyril Henry Hoskins, who wrote, he claimed, under the direction of the spirit of a deceased lama, Lobsang Rampa: a mishmash of occult, theosophical and meta-physical speculation dressed up in a Tibetan robe, his books read like adventure stories, and enjoyed great popularity during the 1960s. David Mellor devoured them. In 1999 Joe Strummer had mentioned to me his brother’s fondness for bodice-ripper black magic novels like those of Dennis Wheatley. But would he have included Lobsang Rampa among the occult works that fascinated David Mellor in what Joe referred to as ‘a cheap paperback way’?

The interests of the younger Mellor boy were also broadening. When he was fifteen, studying for his ‘O’ level GCEs in the fifth form, John Mellor was a member of the school’s rugby Second XV team, playing in the line, either as a winger or a three-quarter, a reflection of the stamina that he would later show on stage and which was already evident in his ability at cross-country running: he was developing into one of the most accomplished long-distance athletes in the school. Perhaps he should have devoted more time to his studies. When he sat his ‘O’ levels in July 1968, he only passed four subjects, English Literature and History (both of which he scraped with the lowest acceptable grade, a 6, which meant 45 to 50 per cent), Art (one grade higher), and a more respectable grade 3 – 60 to 65 per cent – in English Language; in the November re-sits that year, he added a grade 6 in Economics and Public Affairs, giving him a total of five ‘O’ levels, the minimum requirement for further education.

By the time ‘Strawberry Fields Forever’ and ‘Penny Lane’ were released as a double A-side in February 1967, John Mellor’s fondness for the Beatles had evaporated. Now he hungrily devoured both the latest ‘underground rock’ music and its early blues progenitors, much of it from revered DJ John Peel’s late-night Perfumed Garden show on Radio London; every week he read Melody Maker from cover to cover, the former jazz-based music weekly having reinvented itself to find a new readership with long articles about ‘serious’ album artists. Like many other adolescent boys in Britain, he was immersing himself in ‘blues’ music, although – as with most of his contemporaries – at first it was a case of white-men-sing-the-blues: John Mellor incessantly played an iconic LP of the time, John Mayall’s 1966 Blues Breakers album, featuring Britain’s first guitar hero, Eric Clapton. Soon he was seeking out the available American imports by Robert Johnson, the godfather of rural blues, as well as records by the British-based American blues artists Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee. He was already in awe of the work of another American expatriate, Jimi Hendrix. When Clapton quit the Mayall group to form Cream with Jack Bruce and Ginger Baker, John Mellor bought all their releases. Other records became part of his daily diet: the iconoclastic first LP by the Velvet Underground, Blood, Sweat and Tears’ Child is Father to the Man, and, the next year, the first album by Led Zeppelin.

Secreted away in their Surrey school, the boarders were not entirely removed from the modern world. There was, for example, that access to a television set: ‘We got a special dispensation,’ remembered fellow diplomat’s son Ken Powell, ‘to watch The Frost Show when the Stones performed “Sympathy for the Devil”.’ On Saturday evenings they were permitted to watch whichever film – usually a war movie or Western – was being screened. ‘Joe and I were allowed one night to watch Psycho. I can remember being terrified in this cavernous room. I can also recall how I once brought back from Cape Town – where my father had been posted – this shark’s tooth that I would wear around my neck. The next thing I saw he was wearing it. And then I reacquired it. He saw this, and a week later he reacquired it. Then I did. This went on for possibly a year. We never discussed it.’ The shark’s tooth drew attention to Johnny’s own teeth. He refused to ever clean them, or visit a dentist. ‘I’ve decided,’ he announced, ‘to let them fall out, then get false ones. It’ll save time.’

Intriguingly, at this zenith of apartheid, Johnny Mellor never questioned Ken Powell about the political situation in South Africa. ‘We weren’t big into social commentary – it was more girls and music,’ said Adrian Greaves. ‘But Johnny Mellor did have a poster up saying, “I’m Backing out of Britain”.’ This poster, a twist on Prime Minister Harold Wilson’s ‘I’m Backing Britain’ campaign, was fixed to the wall of the study that Greaves by now shared with Mellor and Paul Buck. The psychedelic poster images of the Beatles that formed part of the British packaging of The White Album also adorned the study’s walls after the record’s release in autumn 1968. Whatever his thoughts on the collective output of John Lennon’s group, Johnny Mellor was taken with the man himself, the ‘difficult’ Beatle forever firing off his judgements on injustice or his thoughts on great rock’n’roll, his hip attitudinizing filtered through a patchouli-oil-stained cloak of state-of-the-art psycho-babble. The study’s facilities included a mono record player, ‘a portable plastic thing, with a speaker in the lid,’ recalled Paul Buck, who remembered the affection that he and Mellor had for Elmer Gantry’s Velvet Opera and for Frank Zappa’s protégé Captain Beefheart and His Magic Band, who had been championed by John Peel when his Safe as Milk album was released in 1967. By the time he was in the Sixth Form John Mellor had suffered a personality change, not necessarily for the better. ‘He had become a distinct Dramatic Society arty type, a bit Marlon Brando-like, a sneer to his lip, no respect for convention,’ remembered Adrian Greaves. ‘When he was around eighteen I found him rather obnoxious. He and Paul Buck got on well, because they were both sneerers.’ Greaves remembered Paul Buck and John Mellor falling for an underground myth by drying banana skins over a Bunsen burner before attempting to smoke them in an effort to get high, to no discernible benefit.

In 1968 a brief scandal had billowed through the school when a girl had been expelled for possession of a small lump of hashish. John Mellor became partial to smoking joints whenever he possibly could – he and Ken Powell had got high that year before they went to their first rock concert, the American blues revivalists Canned Heat, at the Fairfield Hall in Croydon, travelling up from the Mellor house just to the south. Richard Evans also remembered going with Johnny Mellor to the same venue to see a show by the group Free.

‘Messing about in the study at school, everything seemed to relate to music,’ said Powell. ‘John would play a game in which he would mime different artists. Two of these I can remember distinctly: he put his hands over his head like an onion-shaped dome, and then he put them out again, as though they were shimmering like water. Who is he referring to? Taj Mahal, of course! Then he mimed some very humble, Uriah Heep-like behaviour, and then tapped his bum – the Humblebums, which was Billy Connolly’s group.’

In the school summer holidays the next year Johnny Mellor, Ken Powell and Paul Buck went to the Jazz and Blues Festival held at Plumpton race track in south-east London, convenient for Upper Warlingham. Among the other Jazz and Blues acts on the bill were those avatars of progressive rock, King Crimson and Yes, and Family, featuring the bleating vocals and manic performance of Roger Chapman, for long a favourite of Johnny Mellor. ‘We slept on the race track in sleeping-bags,’ remembered Ken Powell. ‘The festival ran for three days. We ate lentils from the Hare Krishna tent: we were hardly the types to take food with us.’

That summer was eventful for Johnny Mellor. Richard Evans had long noted Johnny’s skills as a visual artist, endlessly drawing and doodling. ‘He was good, a hugely talented cartoonist. Cartoons were his thing – he had that creativity to do Gerald Scarfe-type satire. Even when very young he had a political awareness in what he was drawing.’ Several of his friends and relatives assumed this was the direction in which Johnny Mellor would pursue a career. Increasingly influenced by pop art and notions of surrealism, as well as by the consumption of cannabis and occasional LSD trips, the youngest Mellor boy would sometimes disappear into creative flights of fancy. One of the most imaginative of these, which created a major furore at 15 Court Farm Road, was when – assisted by Richard Evans – he took a can of blue emulsion paint into the garden and painted all the apples on the trees blue. ‘His father went mad. But we thought it was great. We spent days over this, painting blue emulsion on these apples.’ Before Ron Mellor discovered what his son had done, Johnny took photographs of the trees; later he included them as an example of his work in his application to art school.

By now Richard Evans was known more usually as ‘Dick the Shit’; the sobriquet was not a character assessment – ‘shit’ was a contemporary term used to describe cannabis and marijuana. After taking his O-levels, Dick the Shit had left school, joining a computer company in Croydon. He had just enough money to buy the cheapest available ‘wreck of a car’, a black Austin A40. Wouldn’t it be a good idea to paint the vehicle a more interesting colour? suggested Johnny Mellor. ‘When he said that, I thought of going to the shop and picking out something like metallic silver. But Joe wasn’t having any of that. He was on a different planet.’ Johnny had a better idea: that they use up the rest of the gallon of blue emulsion he had bought to paint the apples; to add some variety he produced more paint, white emulsion this time. ‘We literally just threw this paint over the car. It went rippling down it, in a Gaudi-esque pattern. We painted in the windows like round TV screens. So now I had this blue and white car. Joe signed it, on the front, just above the window-screen.’

That summer Pink Floyd played a free concert in London’s Hyde Park. The pair of Upper Warlingham boys drove up to it in the blue-and-white Austin. ‘We didn’t bother parking, we just drove over the grass and got out of it. It was like art, we just left it,’ recalled Richard Evans. Predictably stoned, they were heading home across the King’s Road and over Albert Bridge when the car’s unusual paint scheme drew the attention of a police vehicle. ‘A policeman says to Joe, “We can do this the easy way or the difficult way. Where’s the acid?” The car hasn’t got any acid in it, but there’s dope. Joe says, “OK, officer, it’s a fair cop. It’s in the battery.” They searched us and the car, but they never found the hash.’

Had the visit to Plumpton festival and the Hyde Park one-day event been a test-run for Johnny Mellor? At the end of those 1969 school holidays the Isle of Wight festival was held, an epic event that had Bob Dylan topping an extraordinary bill, among them the Who, and attracted an audience of a quarter of a million. Johnny went with Dick the Shit in the psychedelic Austin. ‘We went to the Isle of Wight a week before, like the way Joe would go to Glastonbury later,’ said Richard Evans. ‘And we stayed there afterwards. We lived there for at least two weeks, building a little camp. It was great.’ The Isle of Wight festival marked Johnny Mellor’s first long-term immersion in an alternative existence. He found that he liked it. And the next year, which featured an equally stellar bill, culminating in the last performance in Britain by Jimi Hendrix, he and Dick the Shit went back again. This time the musical extravaganza ended in a state of nearanarchy as Ladbroke Grove agit-prop hippie group Hawkwind established an alternative festival on a hill overlooking the site. Johnny Mellor liked that even more: Hawkwind became for long one of his favourite groups.

Late in 1969 Ron and Anna Mellor returned to Britain from their posting in Malawi. From now on Ron, who was now fifty-three, would travel daily up to the Foreign Office in Whitehall: in the 1970 New Year’s Day honours list he received an MBE. That Christmas of 1969 Johnny Mellor persuaded Ron and Anna to let him throw a party at 15 Court Farm Road, the only one he held there. The event turned out to be a little different from the social events with which his parents had been familiar at overseas diplomatic functions. Their son photocopied invitations describing how to get to the Mellor family home. Like any apprehensive host he was concerned that the event would run smoothly. Anxiously he wrote to Paul Buck, who had left CLFS the previous summer, at his home in East Sussex. He’d invited ninety people, he told his friend, before getting to the heart of his worries: ‘“How long does it take to drink a pint of beer? About 10 minutes,” he said. So he’s imagining the whole party running dry in ten minutes. It didn’t.’

‘By 8.30 in the evening no one was left standing,’ said Ken Powell, ‘not because of alcohol or other substances, but because of romantic inclinations. People were all over each other: there wasn’t a single space on the couch, or on the floor.’ Ron and Anna kept discreetly out of the way, until at the end of the evening there was some disagreement between Ron and his youngest son. ‘I remember at the end,’ said Paul Buck, ‘his father wasn’t happy about something, and Joe said, “Yeah, well it’s my pigeon now, isn’t it?” I can remember that phrase, because I hadn’t heard it before.’

Earlier that year Adrian Greaves had also thrown a party. By now Joe had a steady girlfriend at CLFS, ‘a lovely girl called Melanie Meakins, with curly black hair and freckles and fresh skin, who was younger than him’. Johnny Mellor spent his entire time at the party in the garden, snuggled up with Melanie inside the tent he had pitched that afternoon. ‘Sexual relationships were mainly between the boarders,’ said Ken Powell. ‘You didn’t have any parental control. And there would be people you were close to, with hormones running around. A highly charged and exciting situation. Nice, really. We were all on heat.’ Johnny Mellor told his friends that he lost his virginity on another weekend visit to Adrian Greaves’ parents’ house. (It is not clear whether or not this was with Melanie.)

In the summer of 1969, when Johnny Mellor was still sixteen, he had gone with his family to the wedding of Stephen Macfarland, a cousin on his father’s side. The Macfarlands lived in Acton in west London. Another guest at the wedding was Gerry King, another paternal cousin, a pretty girl: ‘John was there, and I had never met him before. He was about sixteen, and I was about twenty-four. We were chatting, and hit it off. We spent the whole wedding day together. In the evening, after all the other guests had left, we all stayed together behind at Stephen’s, all the young people. I really, really liked him. I could feel his charisma. I could feel that he was different. He told me about all his dreams, that he was really going to do something with his life – though he didn’t say what. He seemed very restless, and he was very articulate. At the end he gave me a coral necklace that he had with him.’

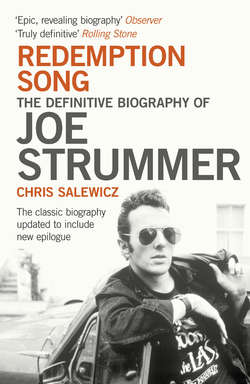

Sixteen-year-old Johnny Mellor, at the wedding of his cousin Stephen Macfarland – Anna Mellor, his mother, is on the left. (Gerry King)

At the wedding reception John Mellor learnt that his cousin had been to school with the Who’s Pete Townshend, and that an early version of the Who had even played in the basement of the house in which the wedding reception was held; Jonathan showed his cousin an acoustic guitar he owned, on which he said Townshend had occasionally played. Johnny Mellor took the guitar back to school and tried out rudimentary chords, notably those of Cream’s version of blues master Willie Dixon’s ‘Spoonful’; although Paul Buck made a bass guitar in woodwork, and would attempt to play with Johnny in their joint study, the Mellor boy was defeated by the need for assiduous practice. But he acquired another ‘instrument’, a feature of his corner of the CLFS study, a portable typewriter, an unusual possession for an English schoolboy: in later life a portable typewriter would often accompany him. Its acquisition at this stage could be an indication that he saw some form of writing as his future.

John Mellor spent the summer of 1969 suitably fuelled on pints of bitter and quid-deals of Lebanese hash, with Paul Buck and two of his friends, Steve White and Pete Silverton, cruising the pubs and lanes of Sussex and Kent in Steve White’s Vauxhall Viva van, close to Pete Silverton’s home town of Tunbridge Wells, looking for parties and girls. ‘It was always good fun,’ remembered White, ‘going to these parties where you’d end up staying for three or four days, lying around in gardens and fields, especially after The Man had come up from Hastings with the gear.’ (Another friend, Andy Secombe, recalls, ‘I remember fetching up in a field in Betchworth in Surrey – I’ve no idea why – at about 2 a.m., and he was jumping up and down with a Party 7 beer can and being very “lit up”.’) ‘I’ve no visual memory of what Joe looked like when I first met him,’ said Silverton, ‘except his hair was long. We all had long hair. This was the late 1960s. But I can remember him writing and doodling in this curled way, with his left hand. He and Paul Buck would incessantly play Gloria by Them, as though it was the only record in the world.’

Like his new crew of compadres, Johnny Mellor was attired in the uniform of the day: flared jeans and jeans jackets, worn with coloured, often check shirts and reasonably tight crew-neck sweaters; an army surplus greatcoat was considered highly desirable, as was a second-hand fur coat, preferably moth-eaten: Johnny Mellor went out of his way to acquire one of these.

Significantly, both Steve White and Pete Silverton remembered being introduced to Johnny Mellor as ‘Woody’. ‘Paul Buck was known as Pablo then,’ added Silverton. ‘He didn’t suddenly become Pablo Labritain in the days of punk – that was something that was going on since he was sixteen.’ Later, Paul Buck – Pablo, as he still prefers to be known – gave me an explanation, suggesting Steve and Pete might be slightly inaccurate. ‘All Captain Beefheart’s Magic Band changed their names. So we did. My name was Pablo, and he was Woolly Census. Next time I saw him after he’d left school, he said “No, no: I’m Woody now.” It was just kids’ stuff.’

In the mythology of Joe Strummer, his ‘Woody’ nickname has always been said to be a tribute to the great American left-wing folk-singer Woody Guthrie, which Joe was happy to go along with – but there seems to have been a much simpler, rather less romantic explanation. It’s easy to see how ‘Woolly’ could mutate to the more direct ‘Woody’ – to Pablo, Johnny Mellor wrote letters signed ‘Wood’. Such nicknaming is an everyday feature of public school life, almost part of a rite of passage in which pupils are given a new identity – as Johnny became ‘Mee-lor’, for example.

Years later, in 1999, Pete Silverton bumped into Joe Strummer in a pub in Primrose Hill. ‘He started telling stories about when I first knew him, which he remembered in great detail, but I don’t. Many of these involved drug-taking in teenage years and police raiding parties – that sort of normal thing. Specifically, he remembered a party at which I convinced the police that nothing untoward was taking place while being totally off my head. Joe remembered that I explained very logically and convincingly to the police there was nothing going on out of the ordinary despite the fact that Pablo was in the bath with his girlfriend. Perhaps that was why the police prolonged the interview, on the grounds that there was a naked woman in the place.’

With Woody, Pablo and Steve White, Pete Silverton gatecrashed parties throughout the summer of 1969. It was, he said, ‘the kind of area where you count the staircases: most of the parties we went to were in two-staircase houses. None of us were rich, but we went to rich girls’ homes on the edge of the country. We were always welcome gatecrashers, but also always over in the corner with the drugs. There was lots of hash around, lots of acid.’ The consumption of drugs, in fact, seemed to take precedence over sex. ‘There was not a high level of sexual activity,’ according to Pete Silverton. ‘A bit, but not a lot. It was more people having sex with their girlfriends, and even then not everybody.’

I mentioned to Silverton that in the opinion of Adrian Greaves Johnny Mellor had by this time become sardonic and sneering, an attitude in which he shared companionship with Paul Buck. ‘That explains how they fitted in with our circle. In our circle they were warm, generous people. There was a sense of superiority amongst all of us of being the coolest people around.’

In a class below Johnny at CLFS was Anne, or Annie, Day, from an army family based in Germany. By the time Annie got to know John in the school choir, he was in the Sixth Form, known as either ‘Woody’ or – another nickname – ‘Johnny Red’. Annie Day became a ‘sort of girlfriend’ of Johnny Mellor: ‘We snogged a bit, but we weren’t full on.’ Perhaps the state of his teeth held him back: ‘When he kissed you he didn’t quite open his mouth. He was always really embarrassed about his teeth.’ There was a considerable age gap between Annie Day and Johnny Mellor; as he matured into the character of Joe Strummer, this became a pattern.

‘We clicked. We just got on well. I think what really cemented our friendship was that every Wednesday afternoon at school, every single class did games. I was excused from games pretty much the whole of the summer. Instead of Joe doing games, he was given free range to use the art department whenever he liked: he was in the Upper Sixth, doing his art A-level, so he used to spend all his time in the art room. At the time he was doing a 27-foot-long painting, and I became his artist’s assistant. I thought he was a really talented artist. I had a conversation with him where I said: “You are going to be really famous and I think you will be famous for your art.”’

For the Christmas celebrations in his final year at CLFS, Johnny Mellor did a series of pop-art-style, comic-strip-like paintings which were put up on display in the school dining-hall. In the manner of Roy Lichtenstein, whose examples of the genre were widely popular, he adorned them with speech bubbles bearing such Marvel-type utterances as ‘BIFF!’ and ‘POW!’ These did not meet with the approval of Mr Michael Kemp, the headmaster. The paintings were only passed for public consumption after each one of them had been altered to the more seasonal ‘Happy Christmas!’

In the Lent edition of The Ashteadian (‘The Journal of City of London Freemen’s School’), in his last year at the school, ‘J.G. Mellor’ is listed as one of the nine boys and eight girls who are school prefects. On page 10, beneath the heading of ‘Dramatic Society’, there is a brief appeal: ‘Again I would like to make a strong plea for material, in the form of songs, sketches or jokes which should be handed into the prefects’ room,’ signed, ‘JOHN MELLOR (Chairman)’. Elsewhere, John Mellor is listed as ‘School cross-country running champion’; surprisingly, as he was hardly the tallest of competitors, on Sports’ Day he also won the high jump. But his approach to school games was flexible; he picked the volleyball teams on the basis of whoever he felt like hanging out and talking with, perfunctorily playing the game whenever teachers turned up.

On Saturday nights he would put on entertainments, ‘off-the-wall things’, said Ken Powell. One such evening was clearly influenced by a parody of The Sound of Music as regularly performed by the then highly popular Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band. It proved inspirational for Andy Secombe: ‘I’d never seen anything like it: it was really fantastic, hysterically funny.’ Adrian Greaves recalls Johnny Mellor appearing alongside him in a production of Oscar Wilde’s The Importance of Being Earnest. ‘He also had a small role in Sandy Wilson’s Free As Air, with one line, “Dinner is served,” delivered in a French accent.’

In Reaction: The School Poetry Magazine, Number 1 (‘A selection of the poems from Reaction will be printed weekly in the Leatherhead Advertiser,’ the reader is advised.), published early in his final year at CLFS, John Mellor has written a poem entitled ‘Drunken Dreams’ – aptly enough, one might think with the benefit of hindsight. It is short, only four lines long, and telling: ‘And the pebbles fight each other as rocks / And my father bends among them / Two hands out-stretching shouting up to me / Not that I can hear.’

In his obituary of Joe in the Washington Post, Desson Thomson, a writer on the paper, recalled his years spent at CLFS. John Mellor, Thomson recalled, was very unlike the other prefects at the school. He had, he said, ‘a fantastic, surrealistic and absurd sense of humour’. ‘Prefects never gave us the time of day, except to beat us or force us to polish their shoes. John Mellor was the one with the implied twinkle. Always playing pranks, mind games. Not as cruel as the others. Always funny. I suddenly remember that he once wore a T-shirt with a heart on it. It said: “In case of emergency, tear out.” … “Thomson, you’re in for the high jump,” he thundered one night, after catching me talking in the dormitory after lights out. I was shaking. Even Mellor could be like the rest of them, at times. This was going to hurt. Solemnly, he made me stand in front of my bed. Withdrew a leather slipper from his foot and told me … to jump over my bed. End of punishment.’ And every single night John Mellor would make the eleven-year-old Desson Thomson sing the Rolling Stones’ Off the Hook. ‘He made me recite the names of the band members. Who plays bass? Bill Wyman, I told him. What about the drummer? Charlie Watts. Right, he said. Who’s your favourite band? The Rolling Stones! Not the poxy Beatles.’