Читать книгу Kansai Cool - Christal Whelan - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

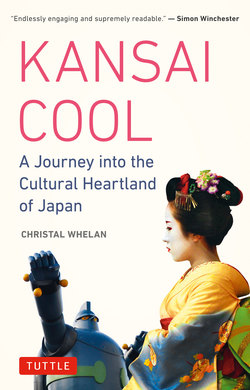

ОглавлениеIntroduction

West of the Toll Gate

Japan is exceedingly mountainous, and long from north to south, and for most of its history has been defined more by region than by nation. A quick look at a nautical map heightens the impression that aside from the four main islands the Japanese archipelago is actually made up of more than three thousand smaller islands with over half the landmass covered by forests. Besides these natural barriers of sea and mountain, for much of the country’s history poor transportation also hindered communication among the various regions. Over time, this insularity fostered a robust regional diversity that remains a vibrant feature of the country even today.

Though Japan has eight regions, this collection of short essays is about only one of them—Kansai—located in the southern-central part of Honshu, Japan’s big middle island. Within this expanse lie seven prefectures equivalent to states or provinces: Kyoto, Nara, Osaka, Hyogo, Shiga, Wakayama, and Mie (1). Roughly nineteen percent of the country’s 127,000 inhabitants reside here. During spring and fall, the numbers swell temporarily as Japanese from all over the country descend on the region to witness the ritual of falling cherry blossoms or the warm spectrum of autumn colors and reconnect to a collective cultural reservoir. After all, Kansai is immensely attractive for its historical depth and because it is the font of much of what is considered quintessentially Japanese by people both inside and outside the country—the tea ceremony, the art of flower arrangement, the performing arts of kabuki, noh, and joruri puppet theater, traditional cuisine, prominent literary works such as The Pillow Book and The Tale of Genji (both written by women), shrine and temple architecture, ancient pilgrimage routes, and the hub of an astonishing variety of Buddhism.

The ancient capitals of Japan—Osaka, Nara, and Kyoto—are all cities that are located in the heartland of Kansai (also called Kinki). In terms of early exchanges with Asia, the Seto Inland Sea, a waterway that separates Honshu from Shikoku island, has served as the great gateway to Japan where ideas and material objects spread from the port of Naniwazu (Osaka) throughout Kansai. From this region, influences radiated outward leaving no part of the country untouched. Nara, the country’s first permanent capital, is also home to the world’s oldest wooden structure—Horyuji temple—a fitting tribute to the city (where deer roam freely) that marked the last stop in the easternmost route of the Silk Road.

The term “Kansai” first emerged during the Heian period (794-1185) as a practical way to distinguish the political and cultural center of the country at that time—basically Nara and Kyoto— from the increasing development of the territory around Japan’s largest plain located in eastern Honshu—the Kanto. Kansai means “west of the tollgate,” and referred to lands in the western central part of Honshu. The tollgate in its name denotes one of the ancient border stations established as early as the 10th century. On the other side of the check point at Otsu in Shiga prefecture lay the region of Kanto meaning “east of the tollgate.” Although the seat of political and economic power has shifted multiple times throughout Japan’s history, Kanto and Kansai have come to represent two distinct cultural and linguistic areas today. In a country where regionalism remains strong, the two stand as shorthand for an internal east-west divide roughly translated as Tokyo and Osaka—the two main economic powerhouses of the nation and the most populous metropolises of Japan.

The characterization of the two regions as much more than geographical entities began to develop in earnest during the Kamakura period (1185-1333) with the burgeoning of a samurai class that spread throughout the center of Honshu in a bid for supremacy. Warriors of the two most powerful clans—the Minamoto and the Taira—struggled and ultimately the Minanmoto gained ascendancy, a victory that precipitated the emperor with the Taira to flee back to western Japan. By 1192, the Minamoto clan’s victory at the Battle of Dan-no-Ura signaled the definitive rise of the Minamoto clan with Minamoto-no-Yoritomo at its head and Japan’s first shogun or Military Commander. The golden age of the Heian era with its nobles and courtly pastimes had begun to fade and a powerful new military orientation with the Kamakura shogunate stood in its stead. Although the capital remained in Kyoto many functions of the government were actually transferred to Kamakura in the Kanto region some 32 miles southwest of Tokyo.

The bifurcation of power divided between the emperor and the shogun and the association of each with distinct regions forms the basis of an enduring Kansai-Kanto rivalry. The symbolic and cultural power of the emperor came to be associated with the Kansai and the political and military power of the state embodied by the shogun with Kanto. Both the Kamakura shogunate and later the Tokugawa were both based in Kanto. But it was during the Tokugawa era that the distinctions between Kansai and Kanto developed with the features recognizable today. In 1603, by dint of his victory at the Battle of Sekigahara, Tokugawa Ieyasu managed to unify a country then composed of small warring states and to establish the seat of his government in Edo (now Tokyo). The next 265 years came to be known as the Edo period (1603-1868) a time of extraordinary economic and cultural development for Japan in which a vibrant merchant class arose alongside the samurai. However, to protect itself from divisive foreign influences, the country adopted a policy of isolation and closed itself to the world with virtually no exchanges. Self-sufficient in all its resources, Japan remained peaceful, productive, and stable during the Edo period. The shogun controlled about one fourth of the country, including Kansai.

A unique feature of the Tokugawa shogunate was the practice by which samurai, as part of their service to their feudal lord or daimyo, resided in Edo in alternating years and offered their services there. Huge retinues of samurai lived in this bustling city at any given time though life there was hugely expensive for them. In the early eighteenth century, Edo was the largest city in the world with an estimated population of 1 to 1.25 million. The traffic back and forth alone from home fief to Edo required a system of post-stations where the samurai could rest along their journey. Merchants set up shops, lodgings, and stores around the many post-stations along the routes. In addition to commuting samurai, travel boomed among the common people who sought spiritual refreshment through pilgrimages. The Ise shrine in Mie, Japan’s most revered Shinto complex, became a favorite destination for pilgrims.

During the Edo period Osaka developed into a great commercial center. With the construction of a canal, merchants could easily transport goods along the whole coast of the Sea of Japan. In addition, a series of kurayashiki, warehouses that served also as sales offices, were built there for various fiefs. Controlled by the shogunate, they gave special privileges to the wholesale dealers and brokers who managed them. The prototype of the Kansai merchant was Takatoshi Mitsui, son of a sake brewer from Mie. The Mitsui family grew to be the largest merchant house of the Tokugawa period and the richest family in Japan. In the late seventeenth century the Mitsuis became the officially chartered merchants for the Tokugawa shogunate.

They opened shops and a department store along a main street in Edo (that later became Mitsukoshi). They were among the first to advertise in Japan by giving away free umbrellas to shoppers in their stores. When it rained, the Mitsui logo could be seen all over the capital. They introduced methods of commerce by means of money when the use of money in trading was virtually unknown. They set up money changing shops in Osaka to convert taxes that were paid in rice into money and even handled the dangerous transfer of funds from Osaka to Edo.

In the mid-nineteenth century Japan ended its long self-imposed seclusion from the rest of the world by reopening its ports and negotiating treaties with the U.S. and certain European nations. As part of a series of reforms initiated by the new and modernizing Meiji government, the capital was transferred once again, but this time out of the Kansai region altogether, and to its present location in Tokyo. This relocation also symbolized the shift from a feudal to a modern society that had required significant revolutionary and visionary forces to topple the shogun, dismantle the powerful and entrenched feudal system, and restore the emperor as head of state. Until this time, the emperor and nobles had always resided in Kansai.

But now the Imperial Palace in Kyoto lay empty. In the 1870s the new government turned its attention to reorganizing the country from a multitude of fiefdoms into forty-seven newly configured administrative territories or prefectures.

Within the new order, Osaka maintained its prestige as a thriving city of commerce that had served as the major supplier of goods to the city of Edo. However, long after this period had passed, the association of samurai with Tokyo (Kanto) and merchants with Osaka (Kansai) became a standard cultural image. In fact, I had read about a typical greeting in Osaka that I was eager to hear: Mookkarimakka? (“Are you making money?”). Fortunately, no one ever greeted me with this salutation. It seems to have disappeared altogether now except perhaps when used as a joke as suggested by DC Palter and Kaoru Slotsve in their book Colloquial Kansai Japanese.

The use of different dialects continues to distinguish the two contrasting regions but with one enormous difference. Once the capital was established in Tokyo, the new government selected an uptown variant of Tokyo dialect as the language to be taught as standard “Japanese” in schools across the country. This is the same language foreigners study when they learn “Japanese” in their own schools and universities. Given the centralization of power today in Tokyo the use of this standard language by broadcasters on NHK national television, Japanese people everywhere have acquired fluency in this officially sanctioned version of Japanese. Nevertheless, people in Kansai are not only proud of their heritage but simply more comfortable using their own dialects in daily conversation.

To spend even a little time in Kyoto or Osaka, is to develop an ear for the cadence and unique vocabulary of Kansai-ben or western dialect that actually consist of many sub-dialects. The first thing that stands out is the ubiquitous sound of “wa” at the end of sentences. This word has no meaning in itself beyond adding emphasis to whatever the speaker is saying. In Kansai both men and women use it frequently. Tokyoites, on the other hand, use the same “wa” at the end of a sentence for emphasis though enunciating it more softly. But in this case, it is an exclusive feature of women’s speech.

As a rule, Kansai dialect is much more melodic because speakers tend to accentuate the first syllable of words while Kanto speech is generally flatter. Kansai natives also often repeat the same word twice as in the commonly heard: Kamahen, kamahen (“I don’t mind.”) as my landlady often said to me to convey empathy. Another striking difference is how the “s” sound in standard Japanese often becomes an “h” in Kansai. Hence, “Mr. Tanaka” or “Ms. Tanaka” is Tanaka-han in Kansai, and Tanaka-san in Tokyo. Verb endings are also different. Endings in –haru and negative -hen contrast with the –ru and -nai. Some vocabulary is simply different such as the word for “chicken meat”: kashiwa in Kansai and tori-niku in most other places. People in Kansai use okini to say “thank you” while arigatoo is the standard phrase in Japanese. Finally, to say “please” when asking for a favor— onegai shimasu (a phrase used constantly in Japan) becomes tanomu wa in Kansai.

Standardized education, national media, and the mobility of people especially moving from rural to urban areas has undeniably weakened dialects, but for the most part I found Kansai-ben still quite robust in Kyoto and parts of Osaka. Only once, when conversing with a man from Yao [southeastern Osaka] did I find myself drifting in and out of comprehension. The interest in regional and prefectural differences in Japan seems to wax and wane as well. In recent years, several books have been written that explore the country’s internal diversity. Referred to as kenminsei, or “prefectural personality”, these works describe the typical behaviors that each prefecture inculcates in the people born and raised in an area with a common history, geography, and environmental conditions.

Anthropologist Takao Sofue was among the first to specialize in the subject as early as the 1970s. Koichi Otani later wrote about the personality of Osakans, referring to his subject as “Osakalogy”. Most recently, marketing consultant Shinichi Yano has promoted prefectural personality as a way to devise sales strategies for various regions and even authored a book for a niche market on the prefectural personalities of Japanese women. Yomiuri TV launched a popular television program in 2007 “Himitsu no Kenmin Show” in which the hosts invite celebrities on the show to represent their own prefecture. After a discussion of the unique features and customs, the celebrity travels live to the prefecture to interview people in what may sometimes turn into a comical attempt to justify the earlier claims.

A common example of a Kansai-Kanto contrast concerns escalator etiquette. In Kansai people typically stand to the right and walkers pass on the left side. In Kanto, on the other hand, everyone stands on the left and walkers pass by on the right. The reason often given (if any) for this predictable set of behaviors is a historical one. Because Tokyo was a city of samurai, even now contemporary people prefer to stay on the left in order to easily draw their swords traditionally kept on the right side. As Osaka was a town of merchants, they still prefer the right side for the protection it offers since traditionally they carried their belongings in the right hand. In any case, one outcome of the current revival of interest in regional or prefectural character has been to raise awareness in Japan of the internal diversity of the country. It also makes it difficult for non-Japanese to speak glibly about the national character of the Japanese when there is actually so much regional and local diversity.

With Kyoto and Nara as the political and cultural center of Japan since the beginning of recorded history, and Shiga, Kobe, and Osaka the great commercial centers during the Edo period, Kansai possesses a complex cultural identity. Even within Kansai itself each prefecture is known for its distinctive character. Kansai people not from Kyoto often describe Kyotoites as “aloof” or “two-faced” since they value reserve and do not easily reveal directly what is on their minds, while Osakans are often called the “Latins of Japan” for being warm, down-to-earth, outgoing, and funny. It was here that Manzai originated—the stand-up comedian duos of the straight man and the funny man. Although both Kyoto and Osaka are known for their delicate cuisine, when compared to each other, the emphasis of Kyoto easily shifts to fashion as the saying demonstrates: Kyo no kidaore, Osaka no Kuidaore (Kyoto people ruin themselves for clothing, and people of Osaka on food). People from Shiga, known for their business savvy, have long cultivated a philosophy of sanpo-yoshi or “three-way satisfaction” in which buyer, seller, and the society at large should all be beneficiaries of any economic transaction for it to be considered a success. From the region have come the founders of such notable companies as the trading giant Marubeni and Wacoal, the famed producer of lingerie.

Sometimes the contrast between Kansai and Kanto is cast as historical pique since Kyoto lost its status as the nation’s capital in the nineteenth century. Nevertheless, Kyoto not only maintains a prestige as the birthplace of Japanese culture but is also frequently charged as the keeper of Japan’s traditions in the present while Tokyo gets regularly blamed for all forms of standardization. While this often smacks of mere caricature, it is intriguing how the distinction between Kansai and Kanto was sufficiently intact as to influence foreign policy during the Allied fire bombings in World War II. While bombs devastated a great deal of Sakai and Osaka, Kyoto, the country’s capital for over a thousand years, was spared because of its cultural and historical significance. Tokyo hardly received such consideration and was not spared from heavy bombing. As a result, Kyoto was able to continue to take pride in its visible heritage of ancient temples and castles while Tokyo lost most of its own. Japan’s modern capital had no choice but to rebuild and modernize. Therefore, much of Tokyo is comparatively new, having been built within just the last six and half decades.

In writing this book I wanted to return to an earlier time when I first set foot in Japan and experienced everything as strangely new. Full of questions but with few ready answers, my enthusiasm carried me in multiple directions at once. At that time, I could have benefited from a guidebook, not one chock-a-block with historical personages and dates too easily forgotten (for such books exist aplenty), but one that would have served more as a cultural compass to allow me to discover patterns and trends and help me find my own way. This book is intended to be just that kind of guide, the one I didn’t have, to assist those who desire to go beyond the cultural stereotypes, predictable tourist sites, and would appreciate a combination of contemporary focus with more interpretive depth while traveling through a vibrant and ever-evolving region. This book is also intended for the many Japanese I have known over the years who for one reason or another expressed regret that they had scant opportunity to explore their own country. I have heard this complaint again and again from Japanese at home and abroad and attempt to respond to it with this book.

My own interest in Japan began as a fascination with the country’s first contact with the West vis-à-vis the arrival of Portuguese and Spanish Jesuits and Franciscans in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. I wondered why a mutually engaging relationship that had lasted a century then deteriorated and precipitated the country into a long era devoid of all international exchanges save but a small community of Dutch and Chinese on a tiny island in Nagasaki built for this sole purpose. The launching point of my interest gradually expanded to encompass an ever broader cultural interest in Japan that sustained me throughout my professional training as an anthropologist. Over the years I have heard many diverse interpretations and characterizations of the country from sociologists, anthropologists, visitors, expats, novelists, psychoanalysts, and policymakers that in their totality conjure up the South Asian parable of the blind men and the elephant.

Asked to determine what an elephant looks like by touching it, each man feeling a single part of the animal—tail, trunk, tusk, leg, ear, and belly—describes the elephant as a very different kind of creature. In the same way, we can read that Japan is a “compact culture” (O-Young Lee), a “dependency culture” (Takeo Doi), a “shame culture” (Ruth Benedict), a “vertical society” (Chie Nakane), a “typhoon mentality” (Edwin Reischauer), a “wrapping culture” (Joy Hendry), a “kimono mind” (Bernard Rudofsky), a “culture of humiliation” (Amélie Nothomb), and the most recent descriptor a “cool culture,” (METI). The actual expression the Ministry of Economy Trade and Industry uses is “Cool Japan” to describe a country in which popular culture has now come to signify the whole in the new geopolitics of soft power officially promoted by the Japanese government today with its ambassadors of cool.

Though I am indebted to all of those mentioned above for teaching me about some aspect of Japan, and to countless others less conducive to sound bytes, I am uncomfortable with master concepts and summations that attempt to capture the main spring of any culture or civilization. However, there are two words that express approaches to life that I have found pervasive throughout Japan. They are: gambaru/gambatte, and kansha. Gambaru can mean “keep trying” or “go for it.” It exhorts a person to make the most sincere effort possible in any undertaking. It also implies that the outcome is far less important than the effort put into something. Ivan Morris captured the sentiment well in his elegant book—The Nobility of Failure: Tragic Heroes in the History of Japan—that tells the stories of various heroes who failed to attain their goals, and often losing their lives in the process. Not victorious in any simplistic way, yet in Japan they are nonetheless considered heroes. What they possessed was a spirit of gambaru as they threw everything they had into their effort. The word kansha translates as “gratitude” and is an orientation that recognizes that a person never accomplishes anything alone but rather is supported throughout life by innumerable people, the natural world, and organizations. The opposite of any notion of self-reliance, it goes a long way in keeping the ego in check.

For the most part, I have attempted through description to avoid grasping another part of the elephant myself. That said, I have allowed a few principles to guide my approach. The over-arching theme of all these chapters is cultural change and the incessant tug-of-war between preservation and innovation. I found this issue particularly acute in Kyoto, the heartland of Japanese tradition where maiko, apprentices to full-fledged geisha, can still be seen stepping from limousines in the Gion district and shuffling to their appointments in steep platform willow-wood pokkuri thongs, while Buddhist monks in straw sandals and broad conical hats that double as umbrellas roam the back streets of the city chanting with begging-bowls in hand and eat only what they receive in alms.

To some extent, the issues raised in these chapters can hardly be confined to the Kansai region alone and are applicable throughout the country. But given the depth of tradition in the Kansai, loss of this same tradition and adaptive innovation strike a particularly poignant note. After all, the roots go deeper and traditions tend to hang on longer here. In addition, these were the specific cases that faced me in my daily environs in Kyoto and are not meant to be exhaustive or to carry the last word. Whenever possible, I compare the Japanese situation to a comparable one outside the country in order to mitigate the tendency to single out Japan as an exception within the world or even within the Asian sphere.

Though I do not deal specifically in this book with the efforts to preserve the traditional houses or machiya, counterparts to that situation exist elsewhere—Germany’s struggle to save the half-timbered houses of Quedinburg from oblivion or Bai Shiyuan’s decades-long crusade in China to save the merchant houses of Huizhou from demolition. My point in making such comparisons is not to trivialize the immediacy of the issue in Japan but rather to open up more space in which to consider the problem and also to prevent a revival of the nihonjinron or “Japanese uniqueness” theories popular intermittently from the 60s through the 1980s. Sometimes I also wish to show the multiple streams of influence, including the intersection between local and global, which have gone into making what we often consider as something distinctly “Japanese” in art or industry.

The more artists and artisans I came to know in Kyoto and Osaka convinced me that they approach their own work in ways that are never static. Yasushi Noguchi, for example, a master craftsman who produces the gold and silver threads used in brocaded obi weaving, spoke of the waning obi industry in the Nishijin district of Kyoto but not in the spirit of a lone dinosaur watching his world disappear around him. Hardly a Luddite, he spoke refreshingly and pragmatically about the situation with which he had wrestled constantly in order to come up with a creative solution.

While Western observers often lament the incursions of modernity into traditional spheres in Japan (and may well romanticize the past), this master craftsman who certainly has much more at stake did not appear to be in the grip of nostalgia. The resilience and flexibility his position represented is what I came to cherish most in the Kansai. I caught a glimpse of it when Noguchi showed me some of his abstract artwork using the same gold and silver leaf on canvas that he also used to roll around the threads for weaving the obi. Engaged with the times, Noguchi had diversified and remained superbly creative in two different spheres. There will probably always be a need to produce obi but not in the quantities of previous eras when the kimono was the daily wear of every Japanese. To preserve continuity amidst the demands of change requires openness and creative response.

This book owes much to The Daily Yomiuri (which reinvented itself as The Japan News in April 2013), an English-language national newspaper, for which I wrote a column “Kansai Cultur-escapes” between 2011-2012. My task was to choose a subject and write about Kansai through an “anthropological lens.” Since the column appeared monthly as a full page in the Sunday travel section, it was imperative that I move beyond commentary and introduce readers to actual places they could visit while showing them photos to further entice them to travel. Because many of the newspaper’s readers are expats who would be bored by places a first-time visitor might enjoy, I sought to introduce venues that would surprise even these old “Japan hands” well versed in the customs and peculiarities of Japan.

Fortunately, I happened to be living in the eastern hills of Kyoto then, just off the Philosopher’s Path, five minutes from one of the greatest temples in Japan—Ginkakuji (Silver Pavilion). The window to my second-floor dwelling faced a small lane up which tourists passed daily to reach several distinguished temples, shrines, and mausoleums further up the hill. As they trundled by in organized tours, motley bands of friends, or couples, I grew accustomed to overhearing snippets of their conversations in dozens of languages of the world, only some of which I understood. The comments were often as instructive as they were entertaining. “Oh no, not another temple!” I once heard a female voice whine below and peeked out my window to see a young woman facing her family while walking backwards in exasperation on a typical muggy summer day in Kyoto. I took the attitudes expressed in these and other conversations I overheard to heart and tried to understand what things people might really want to see and learn about. If that same young woman were to understand more precisely what life in a temple was like she might actually want to visit more of them.

I concluded generally that it was always useful to introduce people to uncommon places, or uncommon aspects of familiar ones often taken for granted and therefore easily neglected. Over the years, I occasionally joined tours in various parts of Kansai. From these experiences, I learned that official Japanese tour guides sometimes engaged in forms of cultural sanitation whereby certain behaviors might be glossed over by relegating them to the remote past. Especially if foreigners were present, the consequence might turn out to be a whitewashing of the present. On a visit to the Imperial Palace, for example, our guide told us that Shinto gates were painted vermilion because “in the olden times Japanese people used to believe in evil spirits” and the color kept the maleficent specters at bay. Yet at the end of the day, most of the Japanese I knew were afraid of jinxes and believed in spirits in one form or another. In their lives they took visible protective measures such as hanging up amulets at home or in the car, wearing Buddhist wrist-rosaries, and attending fire ceremonies to appease unidentified spirits or those of their known ancestors. For whose benefit was it then to present Japan in a secular light?

These essays fall into six broad categories—nature, industry, place, arts, youth culture, and religion. This division serves only as a convenient reference for the reader who might like to skip around the book rather than read from cover to cover. The chapters are meant to present a subject and introduce at the very least, one related place to explore. When I introduce shops, as in the case of the chapter on Issey Miyake, this is because aside from the fashion designer’s Tokyo museum—21_21 Design Sight—free-standing boutiques or those inside department stores are the only public places where it is possible to view his fashion collections. Or in the chapter on toilets, I would not expect everyone to be inspired to go on a religious retreat where toilet cleaning is the central spiritual practice. But just knowing about a utopian community that promotes this method as a means to diminish the ego helps sensitize the reader to the ways in which new spiritualities draw on tradition and certainly makes the next visit to the bathroom a lot more fun. It should also engender a greater appreciation of the fact that Japan simply has the most advanced toilet technology on the planet.

The chapter on Japanese cuisine raises an old question of native versus newcomer, an issue as relevant to people as to plants. At what point is an exotic cultivar or imported vegetable finally considered Japanese? Does it take thirty, a hundred, or perhaps two hundred years? In an age of intensifying globalization the flows of influence hardly ever move in one direction anymore. This is patently clear in the discussion about the father of Japanese animation—Tezuka Osamu—and the multiple cultural streams from which he drew. Cosplay represents another case of cultural interpenetration—an American export from the world of sci-fi conventions ricochets back to the U.S. after blossoming into a full-fledged subculture in Japan. Once re-imported here, cosplayers make every effort to preserve the distinctly Japanese orientation of the practice. Origins get lost and are perhaps meaningless in these cases.

New trends are always emerging and older ones morphing into new forms or disappearing altogether. Youth culture in particular is a huge shape-shifting category. Although I wrote about Lolita fashion, anime, and manga there is another trend gaining steady momentum that I reluctantly skipped over. The Yama Gaaru or Mountain Girl movement that has swept across the country has a lively and active group of young women in Kyoto. Into a single genre they combine outdoor sports such as trekking, climbing, and camping with fashion and spirituality. Mountain Girls dedicate themselves to learning outdoor survival skills that involve chainsaws and woodworking in order to build shelters in teams. These young women dress attractively in rustic-chic fashion of the sort found in upscale sports-stores such as Mont Bell. For treks they may use Nordic walking sticks, colorful and well-designed backpacks, and wear nearly weightless and quilted, knee-length wrap-around mountain-skirts. Their destinations are usually not the classic historical sites but instead one of the many designated power spots in the country.

The term “power spot” was first coined in the 1990s by psychic spoon-bending Kiyota Masuaki to refer to places where the earth is believed to emit a great spiritual healing energy. As the trend picked up books began to appear on the subject. Teruo Wakatsuki Yuu came up with seventy-nine such spots after traveling from Hokkaido to Okinawa. Power spot tourism has gained momentum in Japan especially among young people. Several of my female students liked to report on them. Three notable power spots included in many lists are: Mt. Fuji in the Kanto, Yakushima, an island off the southern tip of Kyushu with giant cryptomeria trees (the inspiration for the forest setting in Miyazaki Hayao’s film Princess Mononoke), and Ise Jingu, in Kansai’s Mie prefecture, the Shinto shrine complex dedicated to the ancestress of the Japanese people—the sun goddess Amaterasu Omikami—who inhabits a symbolic realm of light, purity, and fertility. One of the features of this recent spiritual trend is that the destinations are not exclusively Japan-centered; power spots have a truly global range. Some Japanese books on the subject may recommend: Mt. Saint Michel in France, Ayers Rock in Australia, the red-rock monoliths of Sedona (Arizona), and the Egyptian pyramids.

Although I have not engaged in power spot tourism per se, I have no doubt discovered powerful spots in Kansai. Mt. Kurama in Kyoto would certainly be one of them. Buried in a mountain valley surrounded by forests is a hot spring with an outdoor bath. In autumn, kites whirl overhead and in winter snow falls softly but the tub is always piping hot. The mountain is also the place where the founder of reiki—Usui Mikao (1865-1926)—came to meditate. A follower of Tendai and later of Shingon Buddhism, Usui received his gift of healing-hands in this mountain in 1914. Though he ultimately left Kansai for Kanto where he opened a clinic in Tokyo to teach his system of reiki, from there his students spread his technique throughout the world. Like so many of Japan’s tangible and intangible gifts to the world, this one, too, originated in Kansai.

When you arrive in Kansai the mountains and oceans will certainly be there to meet you, and in all likelihood the temples too, but many of the places described in this book—restaurants, cafes, and shops—are highly vulnerable to the vicissitudes of time. There may be changes in location, development projects beyond a proprietor’s control, economic vagaries, or other unforeseen events in the decades to come. In spite of changes that may arise, may you always find what you are looking for from this day forward.

Notes

1 Sometimes Fukui, Tokushima, and Tottori are included as a part of Kansai.

References

Foundation for Kansai Region Promotion. Kansai Window. www.kansai.gr.jp/en/index.html

Ishikawa Eisuke. Japan in the Edo Period: An Ecologically Conscious Society (Oedo ekoroji jijo). Kodansha Publishing Co., Tokyo, 2000. http://www.resilience.org/stories/2005-04-05/japans-sustainable-society-edo-period-1603-1867

Maxwell, Catherine. “Japan’s Regional Diversity: Kansai vs. Kanto,” Omusubi No. 3. Sidney, 2005

Russel, Oland. The House of Mitsui. Little Brown and Company, Boston, 1939.

Sofue Takao. Kenminsei no Ningengaku. Chikuma Shobo. Tokyo, 2012.