Читать книгу Raven's Cry - Christie Harris - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

PREFACE

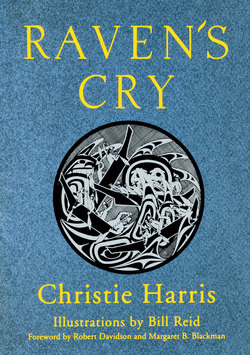

ОглавлениеRAVEN’S CRY is the story of three great and greatly gifted Haida Eagle chiefs caught in the tragedy of culture contact along our northwest coast. It is a true story, as a storyteller sees the truth, through the eyes and passions of her characters—a story to whose telling many people contributed. Those contributions I now wish to acknowledge.

When I moved to Prince Rupert, British Columbia, in 1958, I had agreed to write a series of half-hour dramatic CBC Radio scripts on “those great old Indian cultures up there” for broadcast to the schools. Sheer enthusiasm for the research plunged me into years of almost total immersion in native culture out in the field as well as in public and private libraries.

Only one topic defeated me. I could not uncover enough information about one immensely gifted Haida artist, Charles Edenshaw, to fill a half-hour of air time. Government sources produced only a few scant pages in a national museum booklet. Clearly, someone had to provide information about Charles Edenshaw. Someone had to write his biography.

It was after leaving Prince Rupert, after writing several books for young people, that I talked to artist Bill Reid in Vancouver. I discovered that he had wanted to write the book, “But writing is too much work.” Also, he was extremely busy with his own jewelry and woodcarving, uncovering the secrets of Haida art for his own work. However, if I wanted to write it, he would willingly serve as my mentor and art consultant—provided I could get some support for the project from the Canada Council.

After initial reluctance to fund a writer who was neither a Haida scholar nor an art connoisseur, the Canada Council approved a modest travel grant for me and an equally modest consultant’s fee for Bill. Then, at Bill’s invitation, I began to spend hours in his studio, listening to his assessment not only of Haida art but also of the tragedy of culture contact, while he worked away on his own art. My gratitude to Bill Reid knows no bounds. He gave me my first genuine appreciation of what had happened to the aboriginal population along the west coast.

What I needed most of all was input from Charles Edenshaw’s family. Bill said little about that, while old friends from the north assured me that the family would never entrust its treasured stories to a white woman. I was actually afraid to tell them I was coming to talk to them. They might say, “Don’t bother!”

Yet, when I arrived in Massett—obviously unexpected—I met Charles Edenshaw’s daughter Florence Davidson as if by arrangement. And when I introduced myself, she said, “We’ve been expecting you. We’re having a reception for you tonight.” The entire extended family turned out to hear what I had to say. And it may have been the objectionable errors in the museum pamphlet I read out to them that led them to agree readily to having Florence tell me about her father.

That summer of ’64 is a treasured highlight of my life. Day after day, while our husbands walked the beaches and talked, I listened to that charming, articulate woman tell me the old family stories—generations of family stories.

When I had heard all her stories, though, I knew that this book had to be more than the biography of her father. It had to be the story of three successive chiefs caught in the terrible tragedy of culture contact. I needed to move to Victoria to put all the family stories into historical context, so we took a beach house at Cordova Bay for a year. And there I received invaluable assistance from my friend Wilson Duff, renowned Haida scholar, curator of anthropology at the British Columbia Provincial Museum and later professor of ethnology at the University of British Columbia.

That year, Inez Mitchell, librarian at the Provincial Archives of British Columbia, was unflagging in her zeal for uncovering source material. And my husband, T. A. Harris, skimmed through endless trading ships’ logs to provide me with authentic scenes involving the people in my story.

As I wrote each chapter, I sent it off to my editor in New York, and she kept writing back, “Can’t you get this Bill Reid to illustrate it?” I kept asking him. He kept saying, “I’m not an illustrator.” But, when he came to Victoria to read the completed manuscript, he went through it in silence, laid it down and said: “That’s not bad. I’ll illustrate it.” Then he climbed the fifty-six steps to his car to fetch the beautiful Killer Whale pin he had engraved and presented it to me.

My publisher in New York, Atheneum, had Wilson Duff officially read the manuscript to check its authenticity. The book was published in 1966. For it, I received a medal in Ottawa from the Canadian Library Association for the book of the year for children and a plaque in Seattle for the Pacific Northwest Booksellers’ Award. The book went out of print a few years ago.

I am delighted that its new publisher, Douglas & McIntyre, has shown such commitment to both accuracy and artistry. And it is a particular pleasure to me that Florence Davidson’s grandson, artist Robert Davidson—who was an interested youth at that long-ago gathering in Massett—has given so generously of his time and his knowledge to write the Foreword and bring this 1992 edition up to date. To him and interested scholars like Margaret Blackman, who also contributed to the Foreword, my gratitude.

Minor changes to the text of the 1966 edition of Raven’s Cry were necessary for this 1992 edition, to take account of information that has surfaced in the intervening years. New Haida spellings of the names of people and places have also been used, provided by Robert Davidson. A glossary at the back of the book provides a list of these new Haida spellings with their more familiar renderings in historical and ethnographic records.

Christie Harris