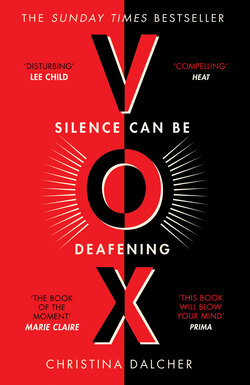

Читать книгу VOX - Christina Dalcher - Страница 20

ОглавлениеTHIRTEEN

Christ, it’s hot in here. There must be a leak in the air-conditioning compressor again. Wouldn’t that be just our luck?

I get up, jeans sticking to the backs of my legs, and go to the kitchen to refill my glass with water. “Patrick, can you give me a hand for a sec?” I call. He makes the rounds in the living room, collecting empty glasses, and joins me.

While I’m pressing one glass after another into the ice dispenser, he takes hold of my left wrist. “You don’t want that back on, do you?”

I shake my head, out of habit.

“You should look at it like a trade, babe. They get something and you get something.”

“I should look at it like what it is,” I say. “Fucking blackmail.”

He sighs like he’s been holding the entire universe in his lungs. “Then do it for the kids’ sake.”

The kids.

Steven doesn’t care. He’s busy filling out college applications and writing admissions essays and boning up for exams, which are right around the corner. Also, he’s been making eyes at Julia King for most of this semester. The twins, only eleven, have soccer and Little League. But there’s Sonia. If I’m going to trade my brain for words, I’ll do it for her.

The hamster wheel in my head must be making noise, because Patrick stops with the water glasses and turns me toward him. “Do it for Sonia.”

“I want more details first.”

Back in the living room, I get them.

Reverend Carl has morphed from politician to salesman. “Your wrist counter stays off for the duration of the project, Dr. McClellan. If you agree, of course. You’ll have a state-of-the-art lab and all the funding and assistance you need. We can”—he checks the paperwork in another folder—“we can offer you a handsome stipend with a bonus if you find a viable cure within the next ninety days.”

“And after that?” I ask, back in my chair with my jeans sticking to me.

“Well—” He turns toward one of the Secret Service men.

The man nods.

“Back to one hundred words a day?” I say.

“Actually, Dr. McClellan—and I’m telling you this in strict confidence, understand?—actually, we’ll be increasing the quota at some point in the future. Once everything gets back on course.”

Well, this is new. I wait to see what other confidential tidbits he’s got up his sleeve.

“Our hope”—Reverend Carl is in full preacher mode now—“is that people will settle down, find their feet in the new rhythm, and we won’t need these silly little bracelets any longer.” He makes a disdainful gesture with his hand, as if he’s talking about a trivial fashion accessory and not a torture device.

Of course, we only feel pain if we flout the rules.

I remember the day when I learned about these rules.

It took only five minutes, there in the bleached white government building office. The men spoke to me, at me, never with me. Patrick would be notified and given instructions; a crew would come to the house—was this evening convenient?—to install cameras at the front and back doors, lock my computer away, and pack up our books, even Sonia’s Baby Learns the Alphabet. The board games went into cardboard boxes; the cardboard boxes went into a closet in Patrick’s office. I was to bring Sonia, barely five years out of my body, to the same place that afternoon so her tiny wrist could be fitted. They showed me a selection, a rainbow of colors I could choose from.

“Pink would be most appropriate for a little girl,” they said.

I pointed to silver for myself and blood red for Sonia. A trivial act of defiance.

One of the men left, and returned with the bracelet that would replace my Apple Watch, the one Patrick had surprised me with for Christmas last year. The metal was light, smooth, an alloy of sorts, unfamiliar to my skin.

He trained the counter to my voice, set it to zero, and sent me home.

Naturally, I didn’t believe a word of it. Not the sketches they showed me in their book of pictures, not the warnings Patrick read aloud to me over tea at our kitchen table. When Steven and his brothers burst in from school, full with news of soccer practice and exam results, while Sonia ignored her dolls, mesmerized by her new shiny red wristband, I opened the dam. My words flew out, unbridled, automatic. The room filled with hundreds of them, all colors and shapes. Mostly blue and sharp.

The pain knocked me flat.

Our bodies have a mechanism, a way to forget physical trauma. As with my non-memories of the pain of birth, I’ve blocked everything associated with that afternoon, everything except the tears in Patrick’s eyes, the shock—what an appropriate term—on my sons’ faces, and Sonia’s delighted squeals as she played with the red device. There’s another thing I remember, the way my little girl raised that cherry red monster to her lips.

It was as if she were kissing it.