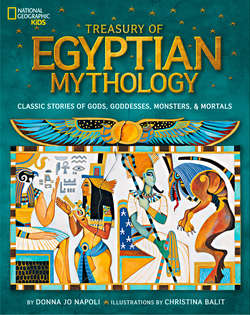

Читать книгу Treasury of Egyptian Mythology: Classic Stories of Gods, Goddesses, Monsters & Mortals - Christina Balit - Страница 10

ОглавлениеTHE GREAT PESEDJET

A Hierarchy of Gods

The sun god Ra created himself, then his children: the air god Shu and the moisture goddess Tefnut. They created their children: the earth god Geb and the sky goddess Nut. Now the ball was rolling; Geb, in all his lush splendor with plants growing from him, and Nut, in all her quiet splendor with winds caressing her, did their part, singly and together. Soon there were five children in the next generation: the goddess Nebet Hut and her husband-brother god Set, the goddess Aset and her husband-brother god Usir, and the god Heru Wer. Ra was progenitor to nine more deities now, the Great Pesedjet. (See illustration)

Ra had been pleased at the triad that he and Shu and Tefnut formed. But now, all these progeny totaled nine, and nine was better. Nine was three squared. A nine-pointed star could be formed by superimposing three identical equilateral triangles, so that each was rotated precisely 40 degrees over from the next lower one. A magic square could be formed by making a matrix of nine cells within a square, each one filled with a distinct numeral from 1 to 9, where the numbers in each row, the numbers in each column, and the numbers in each of the two diagonals added up to the same total. The geometric and algebraic games one could play with nine were a delight. They were a promise of an extraordinary future. And the best thing about the Great Pesedjet was that Ra’s great-grandson Heru Wer was really just the embodiment of Ra himself at midday. So Ra could count himself as part of this miraculous nine. Ra was pleased beyond measure.

Hut Heru was grace itself, enriching the world with the joys of the senses. She was dance and music, inextricably intertwined, and decoratively beautiful, night and day.

That pleasure excited Ra into an even more heated frenzy of creativity that needed to live up to the cleverness of the number nine. The molten flow that had emerged from the watery Nun with Ra’s first words still sizzled. It now inspired Ra. With flame coming from his pointing finger he made the basic elements to build all things. He started with iron and blew it over this rapidly forming ball of a world. It glittered golden. A royal satisfaction enveloped Ra; this was fated to be his color, the rightful color of the father of everything and everyone.

But the world needed more colors. Another jab of Ra’s fire fingertip scattered red lithium to the winds. Next calcium burned bright orange. Then sodium flamed yellow, copper sparkled green, selenium glowed blue, cesium flashed indigo, potassium gave violet luster.

The luminosity of colors seduced Ra’s new eye to step forward as a goddess, and she called herself Hut Heru. She danced over the earth, on which the iron had now cooled into a crust, and laughed, filling the cosmos with music. The twirling of her skirts swished the remaining gassy colors high. When the sun god Ra shone his light through the moisture goddess Tefnut, a rainbow arched across the world, echoing the arched body of Nut, the daughter of Tefnut and Shu.

Hut Heru didn’t always dance, though. She loved night. She lay back in those hours and gazed upward into nothingness. So she wanted calming colors for those quiet times. Ra knew this, of course, for Hut Heru was his very eye. With a scorching finger, he made the silver of aluminum. From it the stars and moon formed, and Hut Heru was glad and grateful.

Now there were nine colors. Nine again. Luscious nine.

Ra shrugged and a cloud of insects filled the air in all imaginable colors. He loved scarabs best. They rolled dung into balls and laid their eggs inside, so the little balls emitted heat as the dung decayed. Later, when the eggs hatched, it seemed like spontaneous generation—like the self-generation of the royal Ra. What charming creatures! Ra took to assuming scarab form and calling himself Ra-Khepra in the morning, when he was just a babe pushing the sun up into the sky. From then on the scarab was sacred before all other creatures.

But the insects swarmed, far too many, plaguing the Pesedjet of deities. So the tongue of Ra stepped forward, as the god Tehuti, and with ever-powerful words he created birds to eat them. Clever Ra was wiser now about the ways of life, so he didn’t stop there; he made Tehuti speak again, and now some birds preyed upon others, to keep the pop-ulations of both insects and birds under control. The master predator and most intelligent was the falcon, and so Ra declared it his bird. Ra often assumed the head of a falcon, particularly in midday at the sun’s zenith. In that form he called himself Ra-Herakhty.

The falcons were such skillful hunters, they would soon have eaten up all the smaller birds except for the fact that they had the snakes to prey upon, as well. Perfect.

There was a whole world to fill, and Ra did it all. Just a blink, a shrug, a chin flick, and wings flapped, feet scurried, bodies wriggled.

And those snakes—good glory, what killers the cobras were! Their tongues picked up the faintest smells and the pits behind their nostrils were so sensitive to heat that they could hunt even at night. Ra had been brilliant to add the sacred iaret to his headdress.

Through words, Ra created little creatures of land and sea and air. Then medium-size ones. Then enormous ones. He created plants and mushrooms. He created rocks and metals and gases. And it was all so painfully beautiful.

Ra gazed at the world through his new eye Hut Heru, wearing his sacred iaret, and the complexity impressed him—the deities, the plants, the beasts, the humans. But somehow those humans kept worrying him. They were cunning in a different way from the beasts. Ra had the terrible sense that he had known those humans would bring trouble, that he had willfully played his part. This was how it had to be. And just as strongly he felt all creation was teetering, close to going out of control.