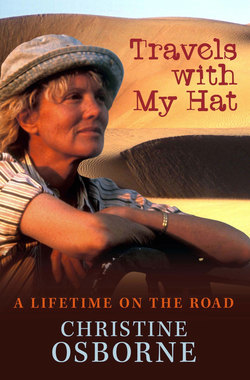

Читать книгу Travels With My Hat: A Lifetime on the Road - Christine Osborne - Страница 4

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Introduction

ОглавлениеI’d noticed her in a waterfront restaurant in Marseilles: an elegant, older woman wearing an exotically patterned kaftan. Seated at a corner table, she was dipping bits of baguette into a steaming bowl of bouillabaisse, the traditional seafood soup in this part of Provence. Where were her friends and family? Was she a traveller, or simply an independent soul enjoying an evening out? Whatever her social situation, I decided she looked like someone who had seen the world. And me. What was I doing in the big French port? I was waiting to board the Pierre Loti, a packet steamer on Messageries Maritimes East Africa run. The Kenyan port of Mombasa was my destination at the time.

I got to thinking about the woman again a few years later, in a café-bar in the Canary Islands. Would this be me one day? I drove my fork into a plate of arroz cubano (fried eggs and bananas served with sticky rice) and wondered how she might have spent her youth. My thoughts were interrupted when a middle-aged man sat down near my table. Cream flannels dangled at his skinny white ankles and a scarlet handkerchief peeped out of the top pocket of a yachting jacket, rather worn at the elbows. Ordering a drink, he scanned the menu and then called across to me.

‘Tell me, what brings a lovely young woman like yourself to the god forsaken island of La Palma?’ He spoke with an impeccable English accent.

‘I’m just travelling about,’ I poured myself a final glass of wine from the earthenware carafe.

‘Yes, but why do you travel and what is your aim? Name’s Milne.’ Christopher Robin Milne—for it was him—looked me in the eye.

‘Forgive me if I appear rude,’ I said. ‘But along with being asked my age (I was twenty-six), I dislike being quizzed about travel. However, if you must know, I’m waiting to catch a banana boat to the Caribbean.’

‘Travel,’ Milne pronounced it gravely, ‘is a form of neurosis.’

‘For you perhaps,’ I called for my bill. ‘But to me, no other experience compares. Especially slow travel and that frisson of setting out to discover something new, only to find that while you were making the trip, the trip was making you.’

Milne looked surprised at this explanation and feeling rather pleased with myself, I stepped out onto the storm-lashed waterfront of Santa Cruz de La Palma, the last port of call for many a boat embarking on a trans-Atlantic voyage.

My thoughts have occasionally returned to this brief encounter. Why do certain individuals refuse to remain hostage to their birthplace and only appear to be happy when on the move? The Scottish writer William Dalrymple suggests that travellers by nature, tend to be rebels and outcasts, and that setting out alone and vulnerable on the road is often a rejection of home. In my own case, it was not a rejection of home, but a ‘walkabout’ in search of the world, since I knew from childhood that a domestic life anchored at the end of the earth in Australia was not for me.

Apart from a conviction in the human need for adventure, I could not contemplate an existence rendered simple by a deadening routine. Catching the same train each morning with the same announcement—Mind the step. Doors closing. Seeing the same pale faces in the office, drinking the same weak coffee from the same clapped-out machine. Sandwich at one. Leave at five. Mind the step. Doors closing. Standing room only. Alone travel replaces the monotony of daily grind.

Few activities generate as much excitement as setting off somewhere foreign, where different landscapes, interesting people, and colourful customs await. Every night after saying my prayers, I would fall asleep to dream of destinations in books signed out by Miss Myrtle, the frizzy-haired librarian who never smiled.

I wanted to visit Burma after reading Ethel Mannin’s Land of the Crested Lion1 and the Greek islands, immortalised by Charmian Clift in Mermaid Singing2. I wanted to stand on the spot where Speke discovered the source of the Nile and to follow Freya Stark, to Damascus and Baghdad. I wanted to dance the tango in Buenos Aires and to meet glamorous characters from The Arabian Nights: sultans, sheikhs and odalisques in harem trousers serving tiny glasses of mint-flavoured tea. And while I loved mum’s roast beef and Yorkshire pudding, I longed to try dishes such as fesanjan, a duck and pomegranate dish from Persia, and the aromatic tajine stews of Berber kitchens in Morocco.

I grew up in Temora, an old goldmining town in the Riverina area of New South Wales, where my father managed the Bank of New South Wales as it was then known. The main street ended in arid plains with scattered eucalypts and a sprinkling of sheep and wheat stations. Beyond was the great Outback, ending on the west Australian coast, 3,218 kilometres (2,000 miles) away. On weekends I used to cycle down past the newsagent and the Greek café, to where the asphalt ended and the dirt road began. Further on, it dipped into a shallow gully where I would sit by a creek and fish for yabbies3 as flocks of green-and-yellow budgerigars wheeled overhead. To go yabbying, you only needed a lump of raw meat dangled from the end of a stick by a string. The yabbies would grab it with a claw and you could drag them ashore, often two or three hanging on at a time. But we didn’t eat them. In the 1950s, along with rabbits, the small crustaceans were considered vermin, so the pleasure lay in simply catching them and throwing them back.

I remember the day at Temora High School when we discussed what we would do in later life. Janice planned to become a teacher. Pam, the Presbyterian minister’s daughter, hoped to train as a hairdresser and the boys all wanted to be rugby league footballers. How they laughed when I announced I was going to see the world. See the world? They found it so hilarious that I never mentioned it again.

On leaving school, I went to Sydney to train as a nurse, only to discover that my calling did not aspire to wearing a starched uniform— the collar used to cut my neck—and to turning my three-piece horsehair mattress daily in Vindin House, the nurses’ home. But gritting my teeth, I persevered and after four years study and graduation, I walked out the iron gates of Royal North Shore Hospital with a vow to travel a year for each year I had spent emptying bedpans. The four years became five and by 1968, I had sailed around the world and had flown across it, still unsure of my direction, until one evening, in the south of France, a Spanish gypsy woman took my hand and read my fortune.

ME (CENTRE) AND RUTH, ROYAL NORTH SHORE HOSPITAL GRADUATES, 1963

‘Usted se convertira en un escritor de viajes,’ she said. And it had dawned: to be a travel writer was my passport to visit foreign lands.

Golden earrings flashing in the candlelight, she stood up in the café and sang a lament to a solitary guitar. I never knew her name, but the craggy-faced guitarist was Manitas de Plata—‘Silver Fingers’—who rose to fame in the 1960s, even playing at a Royal Variety performance in London, my eventual home.

That night in Les Saintes Maries de la Mer, I dreamt of the white horses and black bulls that still roam the Camargue and of the annual festival when gypsies from all over Europe come to venerate their patron saint, Sarah le Noir whose statue stands in the church. And next morning, ears still ringing with the flamenco, I wrote a story about the festival which was published in the Sydney Morning Herald.

It was an auspicious start. The newspaper accepted a second article on Djerba, the Mediterranean island of Ulysses and the lotus-eaters, a third on Djibouti which I’d visited on the Pierre Loti and a fourth on Spain, and unwilling to surrender myself to a sedentary life, I kept on travelling, writing and taking photographs. It was not going to make my fortune, but I never looked back, only forward to the next adventure and interesting encounters with people from all walks of life.

Although I have lived in London for thirty-five years, I am still awestruck by the sight of the Tower of London, built by William the Conqueror and Westminster Abbey, constructed five hundred years before Captain Cook discovered Australia. Dirty and overcrowded London may be, but it is an ideal base to travel from one country to another, and my flat near the river Thames is filled with artefacts collected in foreign lands.

In my living room, an African voodoo mask hangs next to a patchwork quilt from Samarkand. A Chinese coffee-table holds a spice box containing fourth century Kushan coins from Gilgit in northern Pakistan, Minaean pottery shards from Baraqish in the Yemen and a speckled egg from Bird Island in the Seychelles. Beside it stand Ashanti fertility dolls from Ghana and a camel skull found in the Wahiba Sands of Oman. A wooden snake, carved by political prisoners in Ethiopia, coils around the staircase; a red rocking horse made in Mumbai has a place in the hall and on the sideboard is a basket from the Banaue rice-terraces in the Philippines containing my collection of ‘world seeds’. There are kapok pods from Indonesia, a huge kernel dropped by the Kigelia africana ‘sausage tree’ in Zambia, ylang-ylang flowers picked on Grande Comore in the Indian Ocean, Zanzibar cloves, palm nuts from Malaysia, tamarind from Thailand, pine cones from the Atlas Mountains of Morocco. There is even a coconut from Tetiaroa, the late Marlon Brando’s island hideaway off Tahiti.

This basket holds a lifetime of travels. Now friends on both sides of the world have encouraged me to share some of the adventures as a freelance photojournalist. Although the thread may zig-zag a little and double-back to events remembered from one place or another, the tales are basically in chronological order and as the last word is written, I cannot help but wonder what will be the next destination on my ticket.

ABOUT TO BOARD THE PIERRE LOTI IN MARSEILLES, AUGUST 1965