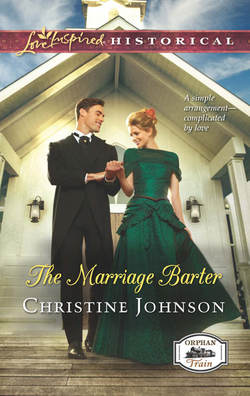

Читать книгу The Marriage Barter - Christine Johnson - Страница 10

ОглавлениеChapter One

Evans Grove, Nebraska

Late April, 1875

Get in, do the job and get out.

It sounded simple, but Wyatt Reed knew that “simple” jobs seldom turned out that way.

All he had to do was escort a bunch of orphans to Greenville. That’s what the town’s wealthiest citizen, Felix Baxter, had told him. Apparently, the kids had gotten off in Evans Grove when robbers held up their train. They were supposed to continue on to Greenville the next day. Two weeks had passed, and still no sign of the children.

Baxter had sent telegrams and only got excuses. The town was fed up with waiting, and wanted the children now. That’s where Wyatt came in.

The thing he couldn’t understand was why. From what he could tell, the orphans had been rounded up out of Eastern cities and sent west by one of those do-gooder charities, the Orphan Salvation Society. Families were found for the children along the way, and Greenville was the final stop. They’d only get the worst of the lot, the children that hadn’t been taken in anywhere else. Logic said this would be a rough bunch of kids, yet Baxter, claiming to speak for the town, had pounded his fist on his desk when demanding they come to Greenville as promised. The town wanted those children badly—too badly.

It made no sense, but Wyatt wasn’t hired to ask questions. He was a tracker. He found what needed finding, and he wasn’t about to turn down the kind of money Baxter had spread out in front of him.

Get in, do the job and get out.

With luck, he’d finish before the catch in this supposedly simple job reared its head. If not, he’d hightail it out of Evans Grove on his trusted mount, Dusty.

Wyatt dismounted in front of the hotel, his bum knee stiff after the twelve-mile ride from Greenville, and surveyed his surroundings. Baxter said he’d find the orphans here. The town was quiet, cozy, the kind of place where everyone knew everyone. No place for him.

He could spot a few signs of last month’s dam break that he’d read about in the newspapers. Water stains marked the wood siding of the hotel at porch height. The lower floor must have escaped flooding. The front door stood open and a couple of gnarled old men sat on the bench outside spitting into a cracked chamber pot that served as a spittoon. Otherwise, the place looked deserted.

“Hotel open?” he asked. Locating eight missing orphans would take more than a couple hours. Any hitch, and he’d need a room.

The men on the porch eyed him warily before the one with a mangled ear managed to grunt in the affirmative.

“Thank you.” Wyatt tipped a finger to his well-worn Stetson. “Got a town hall?”

The cabbage-eared man pointed north, across the street and toward a grove of hackberry trees. Beyond them stood a single-story building large enough to house a meeting room. Must be the place, but would the mayor be there at four-thirty in the afternoon? In towns this small, the mayor usually worked his business by day and officiated in the evening.

He absently patted his ill-tempered Arabian. The horse nipped at his hand as if to tell Wyatt that he should settle them both for the night, but he wanted to see what he was up against. When a boy came bounding out of the hotel, eager to set Wyatt and Dusty up with quarters, Wyatt let him lead the horse to the livery but told the lad he’d register for a room later. For now, he had business to attend to.

First step in tracking is to get your bearings. Wyatt looked past the hotel to a saloon. Piano music tinkled out the open door. Some men fell prey to the lure of whiskey and gambling. In the end, they always lost. Wyatt should know. He’d done his share of stumbling in the war, but he hadn’t touched a drop since the march through Georgia. He set his jaw against the swell of memory.

He had a job to do. The sooner he got it done, the better. Baxter had only given him a quarter of the fee up front. The rest would come upon completion.

He looked past the saloon to the creek. Piles of brick and lumber stood between the grain mill and the other creek-side buildings that had suffered the greatest damage. Rebuilding had already begun.

In the opposite direction, the street stretched east toward a pretty little church with a white steeple pointed high into the blue sky. It could have been plunked down here from any New England town. That old longing for the faith he used to know welled up out of nowhere. Wyatt pushed it aside. God wouldn’t want someone like him.

Beyond the church loomed an unmarked building and then the general store. Wyatt strolled in that direction. A wagon rumbled past, and several women picked their way around muddy potholes. One glanced his way, and he nodded politely. She looked away and whispered to her companion, probably wondering who he was. This sure wasn’t a town where a stranger could go unnoticed.

The cries of children rang out in the distance. The orphans? Or just the local boys and girls? He had no way of knowing. Orphans didn’t wear signs. They didn’t look any different than any other child. Except, like him, they didn’t have a home. Like him, they belonged to no one. Like him, their future looked bleak, and they’d know it. They wouldn’t be laughing and squealing. Those playing children couldn’t be the orphans. No, orphans didn’t belong in a hopeful town with scrubbed buildings and spring blossoms any more than he did.

He absently patted the front of his buckskin jacket and his too-thin wallet. After this job, he’d have enough to settle in San Francisco. He wouldn’t have to track another fugitive or desperate soul. Maybe he’d open a shop, do something respectable. Yep, once he got paid in full, he’d never again have to take orders from men whose honor he couldn’t trust. But he hadn’t gotten paid yet.

Wyatt had lived in Greenville less than two months, but it was long enough to hear rumors about Baxter that made him doubt the man’s sunny promise of a simple, quick and completely legal job.

“Mamaaaaaa!”

The plaintive cry halted Wyatt in his tracks. A child. Very young. Female. His tracker’s instinct clicked into place. Her hiccups and wordless sobs came from very close, between the church and the unmarked building. These weren’t the ordinary cries of childhood. This girl was terrified.

He slipped into the narrow alley between buildings, but a pile of empty crates blocked his view.

“Ma.” Hiccup. “Ma.”

Wyatt paused before the crates. What was he doing? He didn’t know the first thing about children, and he didn’t know a soul in this town. Where would he take her once he found her?

He started to back away until a string of unintelligible words came out at a fevered pitch, followed by what sounded like choking. If someone didn’t calm that child down, she’d stop breathing. Seeing as he was the only one nearby, that someone would have to be him.

He skirted the pile of empty crates, but she wasn’t there. He followed the sobs to the back of the building and a muddy lane where a small, thin child with raven-black pigtails sat in the dirt. He wasn’t much of a judge of children’s ages, but she looked younger than school-age. Maybe three or four. Too young to be wandering around on her own.

Wyatt hesitated, unsure what to do as she lifted her tear-stained face to take in his considerable height. The sobs stopped. Her blue eyes widened so big they seemed to take over her whole face. One grubby hand went into her mouth, just like...

Wyatt stared.

By all the stars in the sky, she looked just like his kid sister, Ava, had at that age. Same pigtails. Same blue eyes. Same need to suck on her fingers.

The girl examined him with curiosity. She’d probably never seen such a tall man.

He knelt, his knee protesting. “Howdy, there. My name’s Wyatt. What’s yours?”

The hand didn’t budge out of her mouth, but those sky-blue eyes continued to stare at him. What lashes! They practically brushed her eyebrows. One day this little girl would break men’s hearts.

Today he needed to find out why she was crying and where she belonged. “Do you have any scrapes or cuts?”

She just stared.

He tried again. “Can you move your legs?” They looked fine, not obviously broken, but he wasn’t a doctor.

She didn’t budge. Clearly she wasn’t going to answer him. Either she was too scared or too shy.

“Are you lost?”

Nothing again.

This was getting frustrating. “Can’t you nod yes or no?”

Naturally, she didn’t move her head one inch.

He rubbed his chin and attempted to ignore his aching knee. He’d try the obvious. “Did you lose your mama?”

“Mama,” she echoed, somehow getting the word out despite the fingers in her mouth.

“Great.” Finally, he was getting somewhere. He stood to take the pressure off his knee. “Where did you last see her?”

She went back to staring silently.

“Of course she doesn’t know that, Reed,” he chided himself. Some tracker he was if he couldn’t remember that a lost child would be disoriented. Trouble was, he couldn’t quite figure out what to do. Missing children weren’t his specialty. He’d never worked with children until this job. Could this child be one of the orphans? He shook off the idea. She’d called for her mother. This girl had a family. In a town as small as Evans Grove, someone would know where to find her ma or pa.

He crouched again, ignoring his knee’s protest. “If I pick you up and walk around town, do you think you can point to the last place you saw your mama?”

The girl answered by sticking out both arms.

She trusted him.

The knowledge kicked him in the gut. No one trusted Wyatt Reed. Not since before the war, anyway. If this girl only knew what he’d done. If she’d heard the screams of terror, she wouldn’t trust him now or ever. But she didn’t know who he was or what he’d done. She just trusted him.

“Get ahold of yourself, Reed.” The girl didn’t know anything about him. She trusted him to get her home, and he’d do it, the same as any paying job.

His big hands more than encircled her tiny waist. He lifted, and her thin arms wound around his neck. So trusting. This girl would crack his tough veneer if he wasn’t careful.

He cleared his throat. “Let’s find that mother of yours.”

And soon. He couldn’t take much more undeserved trust.

* * *

Charlotte Miller fingered the paltry selection of ribbons in Gavin’s General Store. The emerald-green one shone against her pale fingers. The lovely ribbon would match her best dress, but she must buy the black. Custom dictated she hide beneath heavy black crepe for the next year or more while mourning the husband she’d never loved.

Charles Miller had treated her kindly, but all his love had been reserved for his deceased first wife. His marriage to Charlotte had been a business arrangement. She’d needed a husband when her parents died months after they arrived in Evans Grove. He’d needed a housekeeper and cook. Simple and sensible. Yet deep down, she’d hoped their marriage would one day develop the warmth and love that would usher in a large family.

She sighed. At least he’d agreed to take in one of the orphan girls. If not for Sasha, she would have no one.

Charlotte cast a glance toward the toys where Sasha and Mrs. Gavin’s granddaughter, Lynette, were playing with the dolls. The two looked so much alike they could have been twins. Each wore their dark hair in pigtails. Today they wore nearly identical dresses in the same shade of blue. The Gavins had stocked a large quantity of that particular fabric, and most of the girls in town sported play dresses in royal blue.

“I’m so sorry for your loss, dearie,” Mrs. Gavin said as she cut a length of ribbon sufficient to adorn Charlotte’s hastily dyed bonnet. “At least you’re still young.” Mrs. Gavin tried to lift her spirits as she handed Charlotte the ribbon.

At thirty-one, Charlotte didn’t feel terribly young. After a year or two of mourning, she’d have lost even more childbearing years.

She dug in her bag for payment, but Mrs. Gavin refused to take her money.

Unbidden shame rose to Charlotte’s cheeks. “Charles provided for me.” Unlike her parents, he’d left her enough to last three or four years if she was frugal. And she would be. Thirteen years might have passed, but not the memory of the empty cupboards and gnawing hunger following her parents’ deaths. Charles’s proposal had filled her belly if not her heart, and for that she would always be grateful. It had taught her to fight for what she needed. Never again would she let herself become that destitute. Never would she let Sasha endure the pain and humiliation she’d faced. “I can pay.”

The plump proprietress patted her hand. “It’s something we do for all widows.”

Widow. The word ricocheted through Charlotte’s head. A widow had few options. If she wanted to provide for Sasha once Charles’s money ran out, she must either work or marry. But what man would marry a woman who appeared unable to bear children? To any outsider, thirteen years of childless marriage meant she was barren.

Sooner rather than later she must find work. She couldn’t run Charles’s wheelwright shop. The flood had destroyed it. Charles’s apprentice had rebuilt the forge portion, and she’d accepted his generous offer to assume Charles’s debt in exchange for the business.

No, she must look elsewhere. Perhaps Mrs. Gavin needed help.

“I wonder if—” she began to ask, but the proprietress had hurried off to help Holly Sanders, the schoolteacher and Charlotte’s friend.

“Miss Sanders,” Mrs. Gavin exclaimed. “I hear congratulations are in order.”

“Congratulations?” Charlotte drew near her friend.

Holly blushed furiously. “Mason proposed.”

“He did? Oh, Holly. How wonderful.” Charlotte enveloped her friend in a hug. “I’m so happy for you.” Truly, she was, though the irony of their situations didn’t elude her. She, once married, was now a widow. Holly, who’d admired Sheriff Mason Wright for ages, would now be married.

Holly pulled away. “Enough about me. How are you doing?”

Charlotte couldn’t believe Holly would think of her at such a time. “I’m doing better. Having Sasha to care for helps pass the time. She’s such a dear.”

“How is she handling it? She seemed so bewildered at first.” Holly had gotten to know all the orphans in her role as part of the orphan selection committee responsible for placing the orphans with families. She’d grown very attached to the children since their arrival in town.

“The poor girl has seen so much death. Losing her parents, and then Charles.” Charlotte shook her head. “I had no idea his heart had weakened.”

“No one did.”

Charlotte fought the rush of memories. “There’s so much to take care of. I should go through his things, but I can’t bring myself to do it.”

“Would you like help?”

Charlotte couldn’t believe Holly would consider helping her when she had a wedding to plan. “Aren’t you busy with the wedding?”

Holly waved a hand. “It won’t be anything fancy. Besides, we haven’t set a date yet. I can certainly manage an hour or two for a friend.”

Then there was no escaping the task. Since Charles’s death, Charlotte had avoided the loft, the place where he’d lived his life apart from her. She’d respected his privacy when he was alive, and now that he was dead, it felt like even more of an intrusion to set foot up there. Maybe Holly’s presence would make it easier.

“Thank you,” she murmured. “I don’t know what to do with it all. Perhaps someone who lost their belongings in the flood could use the clothes, but who?”

“I’ll ask around.” Holly smiled encouragingly and again grasped her hand. “Shall we do it Saturday morning?”

So soon? Charlotte’s heart sank. She didn’t know if she could face the task, but it must be done. She stiffened her resolve. “Saturday.”

“Anything else, Miss Sanders?” asked Mrs. Gavin as the busybody spinster Beatrice Ward stepped into the store.

Considering the glare Miss Ward cast at Holly, she’d heard the news of the engagement and disapproved. Charlotte wondered if she had any reason to dislike the match, or if she simply felt no one should make major decisions in town without consulting her.

“Not today.” But Holly’s gaze drifted toward the dress goods after Mrs. Gavin left to wait on Beatrice. “I must admit that rose-colored satin is pretty.”

Holly’s uncharacteristic interest in fabric caught Charlotte’s attention. Of course! Holly needed a wedding dress, something that would show off the beauty she didn’t realize she had.

“The color suits you,” she urged. “It would make a lovely gown, wouldn’t it? Oh, Holly, let me make it for you—as a gift.”

Holly cast aside the idea. “No, no, it would be frivolous. I’ll wear the dress I wore to Newfield.”

Charlotte couldn’t let her friend get married in a travel suit. Her vow of frugality evaporated in the face of a friend in need. She would make that dress, whether Holly approved or not. It was a gift, and gifts didn’t require approval.

“I’ll make it in the latest fashion,” she insisted. “Mason’s heart will stop when he sees you walk down the aisle.”

“No, please,” Holly said frantically as Beatrice Ward drifted closer. “Thank you, but no.” Her gaze darted toward Beatrice. “I should get back to the schoolhouse. I have so much work to do before school tomorrow.”

Work. If Charlotte was going to make Charles’s money last more than a few years, she needed to ask Mrs. Gavin if the store was hiring, but she hesitated with Beatrice within earshot. The woman opposed letting any of the orphans stay in Evans Grove. Worse, she was on the orphan selection committee. According to Holly, the mayor had given Beatrice the position in an attempt to placate her, but the woman had done everything to thwart placements. If she thought Charlotte didn’t have enough money to raise a child, then she’d scheme to take Sasha away. No, she’d have to ask Mrs. Gavin about work later.

“I’ll see you Saturday,” she said to Holly. “Eight o’clock?”

Holly nodded. “Saturday morning it is. Say hello to Sasha for me. I look forward to having her in school after summer.”

She darted off, leaving Charlotte stunned. Sasha in school? So soon? The summer would flit by. Why, Charlotte had barely enjoyed two weeks with her.

She turned to retrieve Sasha from the toy display and saw the girl gazing at the expensive doll with the porcelain head and sky-blue dress. It was beautiful but far too dear. She’d make Sasha a pretty doll with black hair and big blue buttons for eyes. She had everything necessary in her sewing basket except the black hair. She eyed the ribbon. A much better use than on her bonnet.

Sasha stood on her tiptoes, her back to Charlotte, and reached for the doll. Her fingers grazed the doll’s feet, and it teetered precariously on the shelf.

“No,” Charlotte cried, running to save the doll from being shattered on the floor below.

The girl turned toward her, eyes wide.

It wasn’t Sasha.

Charlotte’s heart stopped. The doll toppled harmlessly onto the shelf, but Charlotte no longer cared about a doll. Her daughter was gone.

“Where’s Sasha?”

Lynette backed away as tears rose in her eyes. “I dunno.”

Charlotte’s heart went out to her. “Oh, Lynette, it’s not your fault.” It’s mine. A sickening feeling grew in the pit of her stomach. She should have watched Sasha more closely. She should have seen her daughter walk away from the toys. “I’m sure Sasha just went to look at something else. I’ll find her.” The words carried more confidence than she felt.

Charlotte swept around the barrels of flour, her black crepe dress rustling as she moved through the store, checking every aisle and corner. Not in the hardware section or meandering among the groceries. Perhaps she’d gone to the candy counter. Charlotte spun around and saw only Mrs. Gavin and Beatrice Ward. Oh, dear.

“Sasha?” Once again she swept the length of the store. Her panic escalated with every step.

Sasha wasn’t anywhere.

Miss Ward looked up sharply, her pinched mouth gloating in triumph. “That’s the way those filthy urchins are. It’s bred into them. I could have told you she’d run off. You can’t trust their type for an instant.”

Charlotte blanched at the cruel words. “She’s only four and doesn’t know her way around town yet.”

“Now, don’t you worry, Mrs. Miller,” Mrs. Gavin said calmly. “She can’t have got far.”

But worry was exactly what Charlotte felt, along with shame and fear that washed through her in ice-cold waves. Why hadn’t she noticed that Sasha had left? She hadn’t even realized the difference between Sasha and Lynette. What sort of mother was she? Now Beatrice Ward would tell everyone what had happened, and they’d say she was unfit to raise a child.

They wouldn’t take Sasha away, would they? Charlotte’s heart rattled against her rib cage. Sasha was all she had, her only family, the only person she had to love.

She raced from the store, her feet barely touching the three wooden steps. She looked left. Then right. Horses. Pedestrians. A stray dog. No little girl.

Where was Sasha?

She ran first one way and then the other. Sasha. Sasha. Her name beat into Charlotte’s brain in time to her pounding footsteps.

Then she saw her. In the arms of a stranger. A tall, lean man with the piercing gaze of a hunter cradled Sasha with the gentleness of a father.

Her steps slowed, stopped.

Starkly handsome, the man’s dark hair swept the collar of his buckskin jacket. Dark whiskers dusted his cheeks. His eyes, shadowed under the brim of his well-worn hat, stared straight at her. He did not smile. He looked like... Charlotte swallowed hard. He looked like an Indian. Or a gunslinger. An outlaw.

Yet Sasha clung to his neck with total trust, her head nestled on his shoulder.

“Sasha?” The word caught in her throat.

The man’s stony gaze swept her from head to toe. He must not have found the assessment pleasing, for his stern expression never changed and he made no move to hand Sasha to her.

Her panic escalated.

Who was this man, and what was he doing with her daughter?

* * *

Wyatt couldn’t stop staring at the woman. Sun-gold ringlets, touched with a hint of sunset, peeked from beneath the black bonnet. The heavy, black dress only made her porcelain skin look more fragile. Clearly, she was in mourning. Just as clearly, she was this girl’s mother, though the two looked nothing alike.

“Sasha.” Her gentle voice trembled.

Sasha? He stiffened at the peculiar name, but the girl stirred and turned to the familiar voice.

“Mama.” The thin little arms reached for the porcelain-skinned woman, who rushed forward.

“Where have you been? Where did you go?” In seconds the girl was out of his arms and into her mother’s. The woman kissed the girl’s dirty face and hair. “Don’t ever leave me again, understand? I was worried to death.”

Instead of answering, the girl burrowed her head into her mother’s perfectly formed shoulder.

The woman nodded at him, half in fear and half with gratitude. “Thank you. You have no idea how worried I...” She gulped and averted her gaze. “Thank you, truly.”

“My pleasure, ma’am.”

He wanted to tip that pretty face up so he could get a second look, but she kept her focus on her daughter.

“Yes, well, I should get home to fix supper.” She backed away a step.

“My name’s Wyatt Reed.” Now, why in blazes had he done that? He liked to keep contact with strangers to a minimum. Get in, do the job and get out. No emotional attachments.

“Charlotte Miller.” Her gaze darted up for a moment, and her cheeks flushed a pretty shade of pink.

He wanted to touch that cheek to see if her skin was as soft as it looked, but beauties like her weren’t meant for men like him. Still, he couldn’t stop staring. A man didn’t see all that many pretty women on the frontier. Who could blame him for taking an extra-long look?

“Like I said, I should go home,” she murmured, again backing away.

He cleared his throat, reluctant to let her go. “I don’t suppose you could tell me where to find the mayor.” It was the only thing he could think to ask, even though he already knew where the town hall was located. “Evans, is it?”

“Yes, Mrs. Evans.” Her pretty little chin thrust out with pride.

“Mrs.?” Baxter hadn’t mentioned that little detail.

“Pauline Evans is a fine mayor, every bit as good as her late husband.” She started out strong defending her mayor, but with every word her certainty faltered, as if she’d lost her nerve.

For some reason, he wanted to encourage her. He dug around for a suitable response and found none. “I have business to take care of. Don’t suppose you’d know where I can find her?”

Again, she ducked her head. “You might try the town hall. If not there, then she’d be at home.”

“Town hall?” He pretended he didn’t know where it was to gain a few more seconds with her.

Her color deepened. “I’ll show you there. It’s on my way.”

A peculiar thrill ran through him. She would willingly walk with him through town? It had been ages since any woman walked in daylight with Wyatt Reed. And this one was a beauty. She’d match up to any ballroom belle back in Illinois.

“Let’s go home,” she whispered to Sasha.

Home. The old ache came back, hard and furious. Wyatt Reed wouldn’t find home until he set foot in San Francisco.

“Can you walk?” Charlotte murmured to Sasha, her face aglow with love for her daughter.

Sasha nodded solemnly and slid to the ground. “Go home.”

For the first time, Wyatt noticed the girl’s peculiar accent. Her voice had been too garbled by tears earlier, but now the foreign lilt was unmistakable. Sasha must not be Charlotte Miller’s natural daughter. A knot formed in his gut. That meant she could be one of the orphans.

His simple job just got a whole lot more difficult.