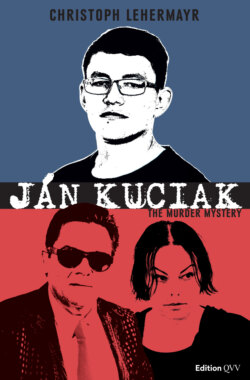

Читать книгу Ján Kuciak - Christoph Lehermayr - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Investigative reporter 2.0

ОглавлениеJán Kuciak is not a daredevil, not someone who corresponds to the image of the reporter as portrayed in movies or TV series. He’s not the type to meet shady characters who pass on information at the back tables of smoky bars, nor does he take delivery of thick packages of documents in some underground car park in Bratislava. Instead, he’s got what a journalist who wants to work investigatively in the internet era needs. Like a mole, he burrows online in publicly accessible data and records. In contrast to Austria, where government secrecy is still enshrined in the constitution, it has long been abolished in Slovakia. The country has far-reaching freedom-of-information laws. Public contracts, for example, only become valid once they’ve been published on the internet. That makes Kuciak’s job a lot easier. He scans court decisions, scours land registers, digs up extracts from the commercial register, looks at mortgage deeds and tracks down offshore letterbox companies. From all of this, Kuciak has the ability to spin threads, draw lines, to recognise networks where others see only chaos. For him, going out and working in the field, as it’s known in the trade, comes, if at all, only at the very end – when he’s collected everything and is able to confront the person in his sights with what he knows.

Doing things this way had long been his dream. But the reality looked very different when, while still a journalism student, he began work at the nation’s most respected financial newspaper five years ago. He stayed for a year and dutifully filled the empty columns with stories. But there were so many times when he would have loved to have dug deeper, asked more questions and found out more. “Work investigatively, are you crazy?” a shocked colleague once asked. “Something like that’s much too dangerous, especially if you step on the wrong person’s toes.” At the time, Kuciak just smiled. “The worst thing that can happen in Slovakia is that they sue you.”

When he left the financial paper at 24, Ján Kuciak wasn’t sure if journalism was for him. He had grown up in a small village in northern Slovakia. No one outside the region knew the place, and if they did they simply thought he was from an impoverished backwater. Him – suddenly a journalist in the capital? There, 50 kilometres from Vienna as the crow flies, was where the young nation’s wealth was concentrated. More and more skyscrapers were shooting up. The glossy investors’ brochures talked about the “Dubai on the Danube” (a pun: Dubaj na Dunaji) that was coming into being. Major corporations were basing themselves in Bratislava, and wages were approaching what was paid just across the border in Austria. The capital was booming and prospering, had traffic jams every wekkend, and Austrian border towns like Kittsee and Hainburg became its suburbs. More and more residents of Bratislava started buying land and houses on the Austrian side because they were much cheaper than in their own capital. Did Ján Kuciak fit into this city? And was he ready to look into the abyss that lay hidden behind the glass facades? It would give him more than enough material.

In the autumn of 2014, Ján Kuciak was determined to find out. The Czech Centre for Investigative Journalism held a workshop to which Slovak university graduates were also invited for the first time. Their mentor was experienced investigative reporter Marek Vagovič, a wiry guy who usually wore a hoody at work, and had occasionally had his tyres slashed or a dead cat dropped on his doorstep. By the end of the course, each team was to develop a story to the point that it could be published. Kuciak was in his element. Together with his colleagues, he decided to follow up an anonymous hint that big pharmaceutical companies had treated Slovak doctors to holidays in the Caribbean. Kuciak drew up organigram charts that showed clearly who the key players in the business were, which connections they had to politics and how contracts were awarded there. Vagovič noticed that Kuciak had a good nose and an ability to connect the dots, while others were at a loss. When confronting doctors and pharmaceutical reps, he remained polite, appeared neither insecure nor arrogant, and argued calmly and objectively. Accusing them of corruption was no mean feat for a budding journalist. Yet Kuciak was sure of himself. The “Hunter-Gatherers”, as his group called themselves, presented their results after three months’ research and came in in second place. Kuciak’s real victory came when his mentor Vagovič told him, “You’re coming with me right away and start to work with us.”