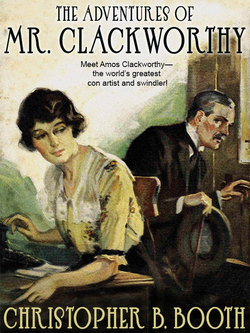

Читать книгу The Adventures of Mr. Clackworthy - Christopher B. Booth - Страница 4

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеMR. CLACKWORTHY TELLS THE TRUTH

Mr. Amos Clackworthy, glancing up from a sheaf of papers which littered the rosewood table in the center of the big living room, smiled. Tilting back in his chair, he lighted one of his expensive cigars, and waited for the outraged monologue which he knew was to follow. It was given without invitation.

“Eighteen seeds for these kicks yesterday—and look at ’em!” exploded James Early. “Cast an eye on ’em; look like they’d been in a battle royal with a couple of hayrakes. You’d think I’d been tryin’ to kick down th’ door of th’ sub-treasury.”

“Let me try my hand at deduction, James,” chuckled Mr. Clackworthy. “My first guess would be that you have ridden home on a surface car during the rush hour.”

“Yeah,” agreed The Early Bird sourly, “all th’ strap-hangers must wear iron cleats on their gunboats; a sardine can is a forty-acre field alongside them street snails.”

Mr. Clackworthy nodded gravely.

“Sit down, James. You will be pleased to know that we are about to capitalize the city’s transportation shortcomings.”

The Early Bird’s gloom disappeared in the sunshine of a spacious smile, as he realized that the master confidence man had designs upon some improperly chaperoned bank account; that they were about to plunge into the exciting whirl of another of Mr. Clackworthy’s delectable adventures.

“Maybe I don’t getcha, but th’ old bean gets th’ notion that you’re gonna grab some coin from th’ sandbag artists what makes th’ long sufferin’ public dig down for eight Lincolns for th’ priv’lege of havin’ their shoes massaged by their fellow passengers. Do I go to th’ head of th’ class?”

“I regret to say that you have guessed wrong, James. Nothing would, I assure you, give me more undiluted pleasure than to coat my fingers with glue, and dip them into the treasure chest of the so-called street-car barons. Possibly we may at some future time devise ways and means of realizing that laudable ambition, but at present no plan presents itself.”

The Early Bird sighed regretfully and again gazed sadly at his mutilated shoes.

“It’s cheaper to ride in taxicabs,” he mourned. Mr. Clackworthy reproved him with a glance; he liked undivided attention when he was about to outline one of his schemes.

“Speak th’ piece, boss; don’t you see my ears quiverin’?” apologized The Early Bird.

“James, I do not believe that any one will deny that the city’s transportation is wholly inadequate. The surface and elevated lines themselves admit it; the population has grown beyond them. High costs of construction preclude any plans of extension, because the banks refuse to accept present inflated values as a fair basis.”

“Shoot lower,” pleaded The Early Bird. “You are three syllables beyond my range.”

“There has been considerable agitation for a subway,” pursued Mr. Clackworthy, “but a ‘tube’ is expensive even in normal times; and now, with labor and material costs sky-high, no popular-priced fare would permit a subway company to pay the interest on its bonds. The subway plan has been rejected as financially unfeasible.”

“You mean th’ nickel-grabbers couldn’t drag in enough jack t’ keep th’ subway out of hock?” paraphrased The Early Bird.

“Precisely, James. The popular demand, as you know, is for a five-cent fare. The city administration has been struggling with all sorts of schemes, municipal ownership being most prominently mentioned, to keep the fare within a nickel.

“Several months ago, you may recall, there was considerable publicity given to the proposed monotrack system which is used in some of the European cities.”

“I gotcha,” agreed The Early Bird. “I seen th’ pictures in th’ papers. A car hangin’ up in th’ air on a wire rope—sort of reminded me of th’ stunt we used to play when I was a kid in Allen’s Alley. We used to give th’ cat a ride by slidin’ a basket along ma’s clothesline.”

Mr. Clackworthy chuckled.

“A bit like that, perhaps, James,” he admitted. “But to get to the point, the strong feature of the monotrack system was the small cost of construction. The single track would be suspended by the support of an iron framework, the power being supplied by the third-rail system. It would mean much less expense in securing right of way, as much less space would be needed. The heavy roadbed required by the elevated would be unnecessary, and the streets would not be darkened by overhead track structure, simply iron posts at the curbing to support the overhanging rail.”

“Why don’t they go ahead and build it?” demanded The Early Bird. “With shoes costing eighteen beanos and—”

“The city administration was much in favor of the plan, and even went so far as to grant a franchise to the Monotrack Transit Company,” interrupted Mr. Clackworthy. “The company was incorporated for two hundred thousand dollars—just for preliminary organization, you know, and its prospects were so bright that the stock sold for par, and went quite readily, too.

“But you can’t float a company on optimism and a franchise, James; when the big bankers turned down the scheme, the price of Monotrack tumbled to ten dollars a share and no takers.

“James, I propose that you and I revive poor, dying Monotrack, as it lies at the door of the stock market, gasping its last.”

The Early Bird’s eyes bulged.

“Great Goshen!” he exclaimed. “You mean your gonna build a car line!”

“How you do jump at conclusions, James. I didn’t say that I intended to build a monotrack system—I am merely going to revive the stock.”

“I getcha,” grinned The Early Bird. “You ain’t gonna build it, you’re just gonna make some of these rich birds think you’re gonna build it.”

“Yes, that’s what I propose to have them think—about one hundred thousand dollars worth,” said Mr. Clackworthy.

II.

Mrs. Clara Cartwright was a sweet but not nearly so trusting a woman as she had been six months before. The reason for her recently developed skepticism regarding the sincerity of mankind reposed carelessly in a bureau drawer of her modest home. Four highly engraved and very prosperous looking stock certificates showed her to be the possessor of two thousand shares of stock in the Monotrack Transit Company.

She had come into possession of this stock upon the payment of sixty thousand dollars in cash, which was every cent that her deeply lamented husband had left her through the medium of a life insurance policy, to smooth the rocky road of otherwise impoverished widowhood. She had purchased the stock upon the advice of Cyrus Prindivale, president of the Suburban Trust Company, who had been her husband’s banker and who, naturally enough, became her trusted business adviser.

Cyrus Prindivale was a moneymaker, attesting to the soundness of his business judgment; but, the vital point which Mrs. Cartwright overlooked was that Mr. Prindivale was quite in the habit of counting his gain, while some one else was tabulating corresponding loss. The suburban banker, to be extremely charitable, was not governed by any exalted rules of ethics, and, except for the rich cloak of respectability that he had wrapped about him, one might have been tempted to charge, in the plainest of words, that he was a crook. Other bankers and business men were accustomed to scrutinize carefully the commas, semicolons, and periods of all papers and documents which involved them in any sort of transaction with Mr. Prindivale.

The financial genius of the somewhat fashionable suburb had been one of the prime movers in the organization of the Monotrack Transit Company. As new corporations are allowed twenty percent of their capital for the floating of their stock and organization purposes, Mr. Prindivale had purchased two thousand shares at a generous discount. It had, in fact, cost him only twenty dollars per share, while others not in on the ground floor, were forced to write their checks for its par value of a hundred dollars.

For a time Mr. Prindivale shared the optimism of the scheme’s other promoters, that Monotrack was going to be a bonanza, but his shrewd little gimletlike eyes, accustomed to looking considerable distances into the future, soon saw the handwriting of the city’s big financiers across the resplendent, gilt-sealed Monotrack certificates, and he read: “Nothing doing.”

At almost precisely the same moment he recalled the sixty thousand dollar balance on the books of his bank, to the credit of Mrs. Clara Cartwright, the full amount of her check from the life insurance company. The very same day Mrs. Cartwright, in her widow’s weeds, happened into the bank, and Mr. Prindivale, in his soft, suave voice, painted a glowing and enticing picture of the wealth that was to be made out of Monotrack Transit. So cleverly did he bait his gold hook that Mrs. Cartwright was pleading with him to be allowed to invest.

And, “only because your husband was such a dear friend of mine, Mrs. Cartwright,” Mr. Prindivale permitted the widow to write him a check for sixty thousand dollars. The price was fixed by a simple process of multiplication; two thousand shares at thirty dollars per share equals sixty thousand dollars—and sixty thousand dollars was all she had.

So Cyrus Prindivale was in actual cash some twenty thousand dollars richer as a result of his almost disastrous dream concerning the success of Monotrack Transit. But there was one thing which Mr. Prindivale did not know; Mrs. Clara Cartwright was a first cousin of Mr. Amos Clackworthy.

III.

On the nineteenth floor of the Great Lakes Building was a most elegantly furnished office suite of two rooms. The lettering on the corridor door informed one that it was occupied by the “Atlas Investment Company.” In the outer room a very pretty young woman was seated before a mahogany typewriter desk; she was reading a popular novel, but the drawer of the desk was conveniently open, ready to conceal this evidence of her lack of occupation; there was also a sheet of paper in the machine, for instant use. The fetching typist was none other than Mrs. George Bascom, wife of one of Mr. Amos Clackworthy’s lieutenants.

A draftsman’s board stood conspicuously in one corner; it held some half completed drawings, bearing the words, “Monotrack Transit Company.” Seated in front of the draftsman’s board was George Bascom, who, at the present moment, was using the point of his dividers to clean his ring, which, in truth, was about the only use he could make of them.

Within the inner room, the door of which was marked “private,” a tall, businesslike man with a superbly trimmed Vandyke beard was seated at his massive mahogany desk; it was, of course, Mr. Clackworthy.

The Early Bird, who had deserted his own desk in the outer office, was seated in the private office, and his eyes roved admiringly about.

“Some joint!” he ejaculated. “Yeah, I’ll say it’s some joint.”

“James,” remonstrated Mr. Clackworthy, “your idiomatic English is most refreshing—on occasions; but it becomes my duty to remind you that you are now the private secretary of a most conservative investment broker, and, as such, you must speak with more refinement.”

“Don’t worry th’ old think-box into a headache,” retorted The Early Bird. “I’ll can th’ lowbrow chatter when th’ lamb appears for shearin’. Huh! I’ll twist th’ old tongue around so’s this bird’ll lamp me and say: ‘Ha-vard, eh?’”

Mr. Clackworthy selected a fresh cigar.

“James,” he mused, “human nature is very contradictory. How often do we reject the truth and yet receive falsehood with childish credulity.”

“Th’ bottomless pit’s only knee-deep compared with your lingo,” mourned The Early Bird, not without admiration for Mr. Clackworthy’s rhetorical facility.

“Here is an example of my philosophy,” continued Mr. Clackworthy. “If I went to the Blackmere Hotel with seventeen trunks and a valet, and announced that I was a millionaire, no one would believe me; yet if I went to the same hotel with the same trappings and denied that I was a millionaire, every one would be quite convinced that I was.

“Well, James, that is the philosophy upon which our present little venture is founded. I do not think that it can fail.”

IV.

Mr. Cyrus Prindivale tilted back in his swivel-chair, and his heavy eyebrows over his beady little eyes contracted into a puzzled frown. Five separate and distinct times he digested the contents of the letter. Carefully he crinkled the edge of the heavy vellum parchment between his critical fingers, and caressed the unimpeachably engraved letters which announced “Atlas Investment Company, 1924-26, Great Lakes Building.” The letterhead was dignified, bespeaking taste and refinement.

“Never heard of ’em,” muttered Mr. Prindivale. “It may amount to something, though.” The letter read:

We are given to understand that you are the owner of two thousand shares of stock in the Monotrack Transit Company. We are delegated by a client of ours to purchase a controlling amount of this stock in order that he may acquire the plans and specifications which belong to the company. We are empowered to offer you the present market price of ten dollars per share. As you are well aware, the revival of the company is a financial impossibility, and our client has no other reason for acquiring this stock than to become the owner in fee simple of its drawings, which, he hopes, may be an asset at some future time.

“Humph!” grunted Mr. Prindivale. “They’re too darn emphatic about wanting ‘only the plans and specifications.’ There is, I suspect, a fox in the henhouse; this is well worth looking into.”

Being, himself, a man of devious methods it was natural that he should look with cautious suspicion on the all too positive frankness of others. With a frown he remembered that he was no longer the possessor of two thousand shares of Monotrack Transit, but, remembering the frantic expostulations of Mrs. Clara Cartwright upon her discovery that her sixty thousand dollars’ worth of elaborate certificates was utterly worthless, he anticipated no difficulty in buying it back for, say, ten dollars a share.

Mr. Prindivale pressed the button on his desk and summoned Dawes, the cashier, who was widely acquainted with many details of the city’s financial circle.

“Dawes,” said Mr. Prindivale, “just who are the Atlas Investment Company?”

Running his fingers through his thin hair, Dawes turned to the “A” compartment of his card-indexed mind, but shook his head.

“Name vaguely familiar, Mr. Prindivale, but I don’t seem to place them,” he replied regretfully. “However, I will find out.”

Dawes stepped to the telephone and called one of the downtown financial houses; a moment later he returned.

“Fisher & Fisher have just told me, Mr. Prindivale, that the Atlas people are an—an—exclusively small concern, soliciting no public business of any character; it is well understood that they are the private agents for a very reputable financier and that, in short, they confine their activities to handling the confidential matters of”—Mr. Dawes paused impressively—“of J. K.”

Mr. Prindivale started violently.

“Merciful Heaven!” he gasped. “J. K.!”

J. K., it must be explained, was a name to conjure with among financial circles; J. K. were the well-known initials of Mr. James K. Easterday, president of three big banks and financial power extraordinary. What he said was financial law.

It was not, to be sure, within Mr. Prindivale’s province to know, that the original Atlas Investment Company had, a few days before, removed their offices from the Great Lakes Building, and that Mr. Clackworthy had hurriedly leased them, neglecting to remove the neat gilt lettering from the door.

V.

As Mr. Prindivale opened the door of 1924 Great Lakes Building, the scene of luxuriant solidity was, somehow, just as he had pictured it. Mrs. George Bascom, her novel hurriedly consigned to the desk drawer as the caller’s shadow fell across the door’s glass panel, hurried her slim fingers over the typewriter keyboard.

Over in the corner George Bascom wrinkled his brow studiously over his draftsman’s board.

“I wish to see Mr. Clackworthy,” announced Mr. Prindivale.

“Busy just at this moment,” politely responded the pretty stenographer and nodded to a chair. The chair, it happened, through careful calculation, was within easy vision of the drafting board. As Mr. Prindivale strained his neck forward for a closer inspection of the drawings, Mr. Bascom glanced at him suspiciously and rudely draped a large piece of paper over the mass of lines and angles, but not before Mr. Prindivale’s sharp little eyes had seen the words “Monotrack Transit Company.”

“Ah!” breathed Mr. Prindivale. “Secrecy! I knew that something was on foot. Foxy old J. K.”

Inside the private office Mr. Clackworthy calmly smoked his cigar, and marked time until the suburban banker should have waited a sufficient length of time. The master confidence man had adopted none of his long list of pseudonyms in this adventure, for he had carefully laid his plans strictly within legal bounds. Even his possession of the abandoned offices of the Atlas Investment Company and the use of that name on his letterheads were entirely according to law. With customary thoroughness for detail he had discovered that the genuine concern had neglected the little formality of registering with the secretary of state, thus leaving it open to use by others; and Mr. Clackworthy had spent the required incorporation fee of appropriating it, free of possible future embarrassing entanglements.

A moment later The Early Bird, hurrying in from the street with an armful of important-looking documents, paused at Mrs. Bascom’s desk. He sighed and mopped his brow.

“Say,” whispered Mrs. Bascom, making sure that it was loud enough to be heard across the room, “you’d better hurry up with those papers; Mr. Clackworthy’s in a big hurry for them—J. K. is in there with him and they want them quick.”

Hastily James Early grabbed up the documents and hurried into the inside office. Eagerly Mr. Prindivale leaned forward to catch a stray word or sentence that might filter through the heavy door, but, to his chagrin, it was sound proof.

“Well, Old Gimlet Eye’s out there waitin’,” he announced.

“Yes, I know.” said Mr. Clackworthy; “Mrs. Bascom pressed the buzzer a moment ago. How do you size him up?”

“As nervous as a Pennsylvania millionaire about to meet King George,” chuckled The Early Bird; “say, that guy—”

“Watch your English, James.”

“Well, as I was gonna say, if you keep that gink—that man, I mean—out there very long he’s gonna wear th’ seat out of his pants th’ way he’s squirming around in th’ chair.”

“That’s fine, James; now you may retire to the outer office while I complete my conference with—ah—J. K. Remember my instructions and follow them to the letter.”

The Early Bird bowed solemnly to the empty chair across from Mr. Clackworthy, grinned, and made for the door.

“I’ve got it down pat,” he said.

In the outer office, James went to his desk, which stood but a few feet from where Mr. Prindivale was seated. Slowly he began to sort over a stack of papers which were heaped in front of him.

Mr. Prindivale edged his chair a few inches closer.

“Have a cigar,” he invited; “fine tobacco, very fine; import ’em myself direct. You have a very nice office here.”

“Uh-huh,” muttered The Early Bird, ignoring the cigar.

“By the way,” probed Mr. Prindivale, “I thought I saw my old friend J. K.—fellow banker of mine, you know—come in just ahead of me, does he transact much business with this firm?”

The Early Bird frowned in apparent annoyance.

“Never heard of ’im,” he mumbled, impolitely taking a cigar from his own pocket and lighting it, but, at the same time, he averted his eyes.

“Never heard of J. K.?” scoffed Mr. Prindivale with entirely justified skepticism. “Ha! Ha! That is quite a joke—sort of in the class with the fellow down in Arkansas who, when the orator shouted: ‘Lincoln is dead,’ declared that he didn’t even know that Lincoln was sick.”

“Never heard of ’im,” repeated The Early Bird with ridiculous obstinacy.

“I see,” nodded Mr. Prindivale, “it’s a dark secret; oh, I’m on.”

“On to what?”

“I know J. K. mighty well—personal friend of mine.”

“Uh-huh,” grunted The Early Bird noncommittally, and his pencil beat a little tattoo on his desk. In accordance with this signal, George Bascom removed the improvised paper shield from the draftsman’s board.

“Bascom!” snapped James. “I don’t want any more work on that just now; hasn’t Mr. Clackworthy told you—”

Hastily Bascom restored the pushpins and Mr. Prindivale’s nostrils quivered.

“Something big on foot—something mighty big,” he thought, and he leaned back in his chair, contracted his eyes thoughtfully and sought to reason it out.

VI.

At the end of thirty minutes Mr. Clackworthy gave the button on his desk three swift jabs and The Early Bird appeared.

“I got ’im goin’,” chuckled James. “He tried to pump me for all he was worth about this J. K. stuff.”

“James, you chew tobacco on occasions, do you not?” queried Mr. Clackworthy.

“Chew!” repeated The Early Bird. “Now, ain’t that a question to ask a guy—with th’ little lamb outside waitin’ for th’ clippers. Gonna get me to sign th’ pledge?”

Mr. Clackworthy took from his desk a fresh plug of natural twist.

“James,” he chuckled, “you know that I abhor the vile habit, even in others; can’t touch it myself; but it now becomes necessary for me to ask you to masticate a generous portion of this plug of tobacco. Strew it around somewhere in the general vicinity of that seventy-five dollar cuspidor. No, I’m not jesting; it’s part of the stage setting.”

Quietly The Early Bird complied.

“That’s all, James,” said Mr. Clackworthy; “I will see Mr. Prindivale now.”

“Holy blue-eyed catfish!” muttered The Early Bird as he retired.

A moment later Mr. Prindivale entered, glancing swiftly about. The first thing that caught his eye was the dark tobacco stains which decorated the floor; he smiled in triumph.

“Ah!” he exclaimed. “Looks as if my old friend J. K. had been here.” J. K. Easterday’s careless way of chewing tobacco was notorious in moneyed circles.

“J. K. Who?” demanded Mr. Clackworthy.

“As if there were more than one J. K. Easterday,” said Mr. Prindivale, exceedingly pleased with himself at this masterful bit of deduction.

“J. K. Easterday has not been here,” declared Mr. Clackworthy with entirely truthful but perhaps unnecessary emphasis. “What would that big fellow be doing up here in my humble domain? You honor me.”

“Have it your way,” said Mr. Prindivale, plainly unconvinced.

“Mr. Prindivale,” began Mr. Clackworthy briskly, “I know that you are a busy man and I will not take your time by lengthy and needless explanations. My letter frankly explained the matter. You have two thousand shares of Monotrack Transit that you couldn’t sell for a scrap of paper. The last selling price was ten dollars a share. For the purpose stated in my letter to you, my client is willing to give you the last quoted market price. That’s the whole thing in a nutshell. Did you bring the shares with you?”

“Tut! Tut!” remonstrated Mr. Prindivale craftily. “Not so fast; I’m too old a head to be rushed like that. Come, my dear sir; give me credit for a little intelligence. When I play stud poker I like to see a few of the cards on the table before I bet.”

“You are intimating—”

“Intimating nothing, Mr. Clackworthy; I know for a positive fact that you’ve got an ace up your sleeve.”

“I have stated the proposition just as it—”

“Just as it isn’t,” charged Mr. Prindivale belligerently. “I’ve got two thousand shares of Monotrack Transit; some one wants them—that somebody happens to be J. K.—and when old J. K. wants anything he pays the price for it—if he has to.”

“You are entirely misleading yourself, Mr. Prindivale,” declared Mr. Clackworthy with a frankness which the suburban banker little suspected. “J. K. Easterday has nothing to do with this matter.”

“Hasn’t, eh?” cried Mr. Prindivale exultantly, pointing his finger at a mass of papers which littered the big mahogany conference table. “Then maybe you can explain that.”

He gestured toward the exposed edge of one of the closely typewritten pages; there, penned in scrawling but entirely legible characters, were the somewhat cryptic letters:

“OKEH JK.”

“Don’t tell me!” he shouted, now thoroughly excited by the importance of his discovery. “That’s J. K. Easterday’s O. K. mark—Okeh, the Indian mark of approval; there are only two men in America who write it that way, one is the President of the United States and the other is J. K. Easterday.”

“Bosh!” retorted Mr. Clackworthy; but, nevertheless, showing considerable chagrin. “I wrote that down there myself—you are jumping at conclusions.” Mr. Clackworthy was showing a most remarkable tenacity for the strict letter of truth.

“Lay the cards down on the table and I’ll talk turkey,” bantered Mr. Prindivale.

“Really, Mr. Prindivale, you are getting rather needlessly excited; I wish to play a game of golf this afternoon and I want to get this business over with. Suppose we say fifteen dollars a share.”

“It cost me more than that; I made up my mind that I’d hold onto that stock until I came out whole on it or let the paper rot.”

“Well, Mr. Prindivale, if you really feel that way about it, possibly we could pay you a price that would permit you to recover your original investment; you did not, I am reliably informed, pay the par value.”

“Ha!” exulted Mr. Prindivale. “I trapped you that time; so it’s worth something after all, eh? How much is it worth? Come across; remember you are not dealing with a grammar-school student, but a business man.”

Mr. Clackworthy stroked his Vandyke beard meditatively; at the same time his foot slid under the desk and touched the tip of the electric button which was secreted there. It connected with a faint-voiced alarm on The Early Bird’s desk, and James Early, in turn, touched a button which connected directly with the telephone on Mr. Clackworthy’s desk. The bell tinkled.

In the act of lifting the receiver from the book, Mr. Clackworthy turned to the suburban banker.

“Granting, for the sake of reaching an agreement, that you paid the par value of one hundred dollars a share and, taking cognizance of your determination to come out whole on it, I am empowered to offer you—”

The bell rang insistently.

“Hello,” said Mr. Clackworthy into the transmitter. “Yes, this is Mr. Clackworthy; yes, Aubuchon—uh-huh—yes, I understand. He’s here now.”

Mr. Prindivale, sensing a personal reference, looked up quickly; he saw that Mr. Clackworthy’s gaze had grown hard and cold; the air of eagerness as he had jockeyed for the best possible price was gone. The banker, with a sinking heart, realized that something had gone wrong.

“Mr. Prindivale,” said Mr. Clackworthy curtly, hanging up the receiver, “there is no need to discuss this matter further. I find that I shall not need to buy the stock from you, after all.”

“But—but—I don’t understand,” stammered Mr. Prindivale.

“Oh, yes, I think you do,” returned Mr. Clackworthy icily. “One of my men has reported to me just now that you sold your Monotrack holdings some months ago—to some woman; we shall, of course, deal directly with the holder of the stock. You almost hooked me, eh?”

Mr. Prindivale grabbed his hat and fled.

VII.

There was a reason for Mr. Prindivale’s precipitate departure. He cursed because the elevators were so slow and bolted out of the entrance to the drug store at the corner where he knew there was a telephone pay station.

His fingers, fumbling with eager haste, turned the leaves of the directory until he found the name of Mrs. Clara Cartwright. It was, of course, a suburban call and he muttered trenchant maledictions for the operator who seemed to deliberately delay his connection. After five anguished and perspiring minutes Mrs. Cartwright’s soft voice identified itself from the other end of the wire.

“Mrs. Cartwright,” gulped Mr. Prindivale, striving to make his tone normal, “about the Monotrack stock which I sold you—er—I have been thinking it over and I realize that it was—er—entirely upon your faith in my advice that you purchased it. I—I could not, in all—er—fairness, expect you to pay for the burden of my—ah—sincere but mistaken judgment, so I have decided to take the stock off your hands without a cent of loss to you and pocket it myself.”

“Oh, Mr. Prindivale! How lovely of you!” exclaimed Mrs. Cartwright, who had been carefully tutored by her cousin’s husband, Mr. Clackworthy, for this identical situation.

“Yes,” went on Mr. Prindivale, “so I will be right out and give you a check.”

“Oh, there is no hurry, Mr. Prindivale, so long as you promise.”

“But there is a hur—I mean that I am in a hurry to get it off my mind. I know you will feel better with things fixed up; I—Well, I might die tonight, you know. There has been no one out to see you about buying the stock, I suppose?”

“Oh, no; who would want to buy it?”

“Oh, of course not; of course not,” assented the banker, “but—um—in case some one did talk to you about it, I would advise you to do nothing until you talk to me.”

“Oh, Mr. Prindivale!” gurgled Mrs. Cartwright. “You are so excited and everything; I do believe that the stock is going up.”

The banker swore under his breath; he was walking on dangerously thin ice.

“Certainly not; that was just—just a little joke,” he amended.

A taxicab driver, bribed with a twenty-dollar bill, broke all the speed records in getting Mr. Prindivale out to the suburb. The banker found Mrs. Cartwright in the sitting room of her modest little home, evidently waiting for him; she had the stock certificates in her hand.

“I’ll just write a check, Mrs. Cartwright,” he said with hardly the ceremony of a greeting.

“Why, Mr. Prindivale!” the widow exclaimed. “You act so excited. I do believe that something has happened to the Monotrack business.”

Mentally the banker reviled woman for her intuitive powers, as he wrote his check.

“Here you are,” he said, unable to keep the eagerness from his voice; “I will take the stock back now—you see I have not allowed you to lose a cent.”

Mrs. Cartwright tilted her chin and firmly put her hand which held the certificates behind her back.

“I’ve got—what do you men call it—a hunch?” she said. “I have decided not to sell for thirty dollars a share!”

Mr. Prindivale tried a bluff; with an anger which was not entirely assumed, he snapped his check book shut and pocketed his pen.

“Just as you will,” he said coldly; “I try to play good Samaritan and am at once suspected of some underhand scheme to cheat you.”

“I—I am sorry if I have misjudged you,” she returned with a show of penitence. “Of course, if you are sincere in your offer, I suppose—” She paused in sudden thought. “But I can’t get rid of that—that hunch; something seems to tell that I should not sell my stock for thirty dollars a share.”

“And I presume,” said Mr. Prindivale with a poorly concealed sarcasm, “that your hunch also tells you just what price you will get.”

“Now, let’s see!” she cried, like a child playing a game and clapping her hands in fun. “Now, isn’t that funny—a figure just pops in my mind—eighty dollars a share!”

“Come, Mrs. Cartwright,” purred Mr. Prindivale in his most persuasive tone, “I’ll tell you what I will do. Since I have caused you quite a little worry over your apparent loss of sixty thousand dollars, I will permit you to make a little profit—out of my own pocket, you know—as a sort of penalty for my mistaken judgment in advising you. I will give you thirty-five dollars a share.”

Mrs. Cartwright laughed, and how was Mr. Prindivale to know that this was the cue for Mrs. Cartwright’s loyal and trusted servant, Amelia, to connect the electric current which caused a telephone bell to ring in another room? The banker was engulfed by apprehension, that might be J. K.’s men seeking to get in touch with her; he was, somehow, almost sure that it was.

“As—as I was saying”—he stumbled.

“Mis’ Cartwright; there’s a man on the phone as wants to talk to you,” said Amelia; “he says his name’s Clack—Clack something.”

“Just a minute, Mr. Prindivale; you will excuse me for a moment.”

“Wait! Wait!” cried Mr. Prindivale wildly. “Let us close this up before you go; now let me see—” He was hastily doing a little problem in mental arithmetic; Clackworthy had promised to pay the par value of one hundred dollars per share, that would be an even two hundred thousand dollars. If he paid Mrs. Cartwright eighty dollars a share that would total one hundred and sixty thousand dollars, and as hard as the bargain was, a forty-thousand-dollar profit as compared with the clean-up of a cool one hundred and forty thousand dollars that he had visioned was, after all, a good killing.

“You said that you would take eighty dollars a share,” pursued the banker.

“Oh, but I was just joking—really; surely you—”

“You gave me your word, your promise, that you would take eighty dollars a share,” insisted Mr. Prindivale. “You can’t back out now; you must let me have it—you must!”

Feverishly he again wrote in his check book; he forced the slip of paper into Mrs. Cartwright’s fingers and almost forcibly tore the stock certificates from her hand. The widow was apparently too bewildered to protest. And before she could find voice, Mr. Prindivale dashed out of the house. He would have been a much surprised and mystified man if he could have seen her rush to the telephone and call a city number and to have heard her words:

“Amos Clackworthy, you darling, darling man! We have met the enemy and his check is ours. I’m going to rush right out, just like you told me, and have it certified—then I will be right down and give you your hundred thousand dollar collection fee. Isn’t it great to have a cousin who has a husband with such a wonderful brain!”

VIII.

And that would end the story, except for Mr. Prindivale being what is sometimes sneeringly referred to as “a rotten loser.”

When the suburban banker trotted triumphantly up to the Great Lakes Building the following day, two thousand shares of Monotrack Transit in his pocket, he was amazed to find the offices of the Atlas Investment Company vacant. It gradually dawned upon him that something was wrong. In his first burst of rage he visited the district attorney’s office and laid bare the amazing story.

The district attorney, viewing the case from all angles, decided that perhaps morally Mr. Cyrus Prindivale had been most thoroughly bunkoed, but that legally he had merely made an unfortunate investment. The district attorney, too, in delving deep into the details, had uncovered the fact that the worthless stock Mr. Prindivale had purchased from Mrs. Cartwright for one hundred and sixty thousand dollars was the same identical and equally worthless stock that he had sold to her for just one hundred thousand dollars less than that amount. And the prosecutor bowed Mr. Prindivale out of the office with scant sympathy.

By rare coincidence, the district attorney was a nephew of no less illustrious person than J. K. Easterday, and that was how “J. K.” got hold of it and may explain an otherwise mysterious communication which Mr. Amos Clackworthy received in his morning mail.

Mr. Clackworthy and The Early Bird were at breakfast when the Japanese boy entered with the postman’s nine o’clock delivery. From under the edge of the white tablecloth protruded the glossy surface of one of The Early Bird’s new twenty-dollar shoes; he glanced at the shining patent leather and grinned.

“Twenty smackers this time—and worth it,” he said. “You gotta pay real dough for kicks these days, and this pair ain’t gonna get chawed up by no plebeian—that’s right, ain’t it—sodbusters. That Monotrack layout sure has improved th’ transportation situation for yours truly, James; I went down on Boul Mich yesterday, and laid out two thousand iron men for th’ niftiest little racer that ever landed a guy in th’ speeders’ court.”

Mr. Clackworthy, laughing silently, as he read the contents of one of the envelopes which he had just opened, tossed it over to The Early Bird.

“Speaking, James, of our most recent adventure,” he said, “you will, I think, find this the crowning touch.”

The Early Bird picked up the sheet of paper; there was but one typewritten sentence which said:

It is gossiped in financial circles that Cyrus Prindivale, an exceedingly shrewd banker, has recently endowed the School of Experience with the munificent gift of one hundred thousand dollars.

Scrawled across one corner in a bold, masterful hand were the letters: “Okeh J. K.”