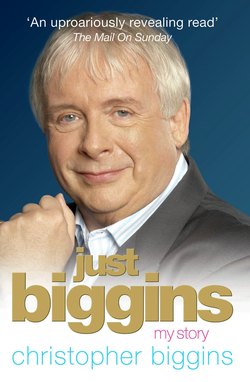

Читать книгу Just Biggins - Christopher Biggins - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

finding my voice

ОглавлениеNext in the cast of characters of our family was Great-Aunt Vi – the biggest snob I ever met. She lived in Faversham in Kent, where she and her husband, Arthur, owned a seed shop in one of the most beautiful buildings in the town. Auntie Vi taught me how to lay a table properly, how to place napkins and how to make a wonderful Victoria sponge. When I went to stay, or she came over to ours, I got bedtime stories in the bath with a glass of ginger wine. I thought it was the height of sophistication.

As far as Mum, Dad and I were concerned, Great-Aunt Vi was a woman with a mission. She hated my Wiltshire burr – Mum had it too – and Dad’s voice annoyed her even more. It had a touch of the north, a touch of cockney and even that joking, Jewish lilt in it for good measure. So good old Great-Aunt Vi paid for the elocution lessons that would turn the Oldham-born, Wiltshire-bred boy into the Christopher Biggins whose voice can boom so loudly today.

Mrs Christian was my elocution teacher. She was a fantastic, wonderful woman and I saw her once or twice a week for private classes at my new school and at her home. These were my My Fair Lady moments. The rain in Spain falls mainly on Salisbury Plain and all that. As the weeks passed, my Wiltshire burr began to fade. But my lessons went on. I think Mrs Christian saw something other than just a strong voice in me. She also taught drama and English at school and was the first to really get me interested in theatre. And she had help. If she had lit the theatrical flames, Mr Lewis, soon to be my music teacher at school, would be the one to fan them.

He was one of the biggest gossips I had ever met. All we did was gossip. To this day all I can play on the piano is ‘Daffodil Dell’ (and I’m not very good at that). But what I missed out on in terms of scales or harmonies I gained in terms of confidence and simple joie de vivre. Mr Lewis was probably a bit effeminate, but I didn’t spot that then and it wouldn’t have made any difference even if I had. There was certainly no element of impropriety in our long, funny theatrical chats. I think Mr Lewis simply saw me as a kindred spirit – albeit a much younger one. Those were lonely times for confirmed bachelors of a certain age. I think I just brightened some of my teacher’s darker days. I let him forget how isolated he might be.

I had started at the private St Probus School for boys at 11. And it had all been a bit of a mess. Much to my dad’s disappointment, I had failed my 11 Plus and so didn’t qualify for the local grammar. Or did I? My father had been talking to some other parents and found out that, because I’d only been ten when I’d taken the exam, a loophole meant I could do a retake. If I passed I would be educated for free and, like I say, Dad loves a bargain. But the timing was all wrong. The day that Dad rushed home to tell us the news, Mum and I were busy buying my brand-new St Probus uniform and paying my fee for the first term.

‘Too late now,’ Dad said when he saw me in all my new finery.

So St Probus it was. And it served me well. I enjoyed school. We were neither a hugely academic nor a hugely sporting place. Just a very relaxed place. And we had a theatre. That would change everything for me.

My first proper stage performance at school was as the Pirate King in The Pirates of Penzance. I was in heaven. I took on as many other roles as possible after Pirates. And at 14 I enjoyed my first, campest, triumph. I played the Ethel Merman part in Call Me Madam. Yes, I think the clues were all there had anyone bothered to look for them. And if my choice of roles didn’t raise eyebrows, my clothes certainly did. For quite some time I insisted on wearing a full-length blue kaftan when my poor mother took me shopping. To this day I can’t remember where on earth I got it from. Sleepy old Salisbury, in the early 1960s, had hardly ever seen the like before. No wonder my mum always wanted to walk a few paces ahead or several paces behind me. No wonder she was mortified when I decided I wanted to stop in a shoe shop one day to see if I could get footwear to match. The girls there barely batted an eyelid. But Mum? She was mortified. Looking back, I can see her point.

My good fortune as a boy was to avoid the total isolation felt by anyone who grows up feeling a little different. I did that because I had a pal called John Brown at my side. We met in my first year at St Probus and were friends from the very start. We’re still friends today, though we see each other far less frequently than we should.

As kids, John and I always had a hoot at theatre rehearsals – and every other moment of the day as well. Neither of us was especially sporty and in particular we both hated cross-country runs. We decided to turn them into cross-country walks. The two of us would amble around picking up flora and fauna and get back to the smelly locker rooms laden with wild flowers and berries.

‘Biggins, come on!’

‘Brown, get running!’

‘Where have you two been?’

Everyone would be yelling for us to hurry up, because the games master said no one could leave until we were all finished. But there was no question of bullying at school, and no taunts about anything other than our lack of athletic skills. This sense of decency and respect came from the top, as it always does.

Our head teacher, Mr French, was very firm but very fair. Yes, he used the threat of the belt to keep us all in line, but I truly don’t see the harm in that. We all learned the boundaries between good and bad behaviour from Mr French. Today we’ve probably gone too far the other way, giving kids too much freedom and not making it clear how they should behave. Mr French never made that mistake. Though I do remember a few oddities. Once he gave us a lecture on gingivitis and dental hygiene. The next day, for reasons I can’t recall, we all rebelled over our school lunches. We threw all the food into the bins. And then in walked Mr French. He made every one of us get a spoon and eat at least a spoonful from the bins. Not exactly hygienic, or great for the gums. But it taught us to keep our rebellions on a smaller scale from then on.

Thinking laterally helped on the cross-country runs as well. John and I realised that we couldn’t keep our classmates waiting every week. And I suddenly found a new way to avoid the run but still get to the finish line on time. Maisie’s house was just outside the school playground, where the races began and ended. So John and I would pop in for a cup of tea and a gossip and emerge when the front-runners headed back past the front door. It was payback time for all those embarrassing bath times.

At the weekend John and I used to spend all our time together as well. We would sit for hours at the Red Lion Hotel having a cheese scone and a thick, milky coffee. We thought of it as utter sophistication. By now I knew a lot about the way you were supposed to behave in hotels. I had my mum’s example, of course. But I had also lapped up all the glamorous stories from my grandmother. She had been a silver service waitress in the Red Lion back at a time when you had to pay the head waiter to get a shift.

‘Always leave a tip,’ she would tell me, remembering how tough it had been when others hadn’t.

‘Always leave a tip,’ my mum would repeat when she knew I was off out with John. But I didn’t always take it seriously. One afternoon, when we really couldn’t make our scones and coffee last any longer, I got a piece of paper and a pen out of my pocket.

‘Tip: Back the first horse at Aintree,’ I wrote, thinking I was hilarious and the first person to come up with a line like that. And if I was wrong on those points I was certainly wrong to think I would get away with it. The waitressing scene in Salisbury was as tight as the acting profession. Mum found out what I had done straight away and I got the biggest bollocking and the hardest slap of my life.

I left school at 16 without, I’m a little embarrassed to say, a single O Level. I’ve no regrets at all in my life. But if I was pushed I’d say I do almost regret not going on to some kind of college. I’d perhaps like to have seen how much more there was to know. I’d like to have learned more, though I don’t know about what. Today I swear that if I won the Lottery and never needed to work again I would fill at least part of my time with study. I’d soak it up in my sixties. All the opportunities I let slip in my teens.

So what would I do for a living?

‘I think I might want to be a vicar.’

That was a bit of a conversation-stopper back at home. My parents took it well and would have helped make it happen if I’d been serious. But I think I was just casting around for something that involved dressing up in costumes and reading things out in front of people.

Before I hit upon the other, blindingly obvious way to make a career out of those activities, I carried on doing odd jobs for my father. I’d always loved watching him work just as much as I loved watching my mother. He was at the top of his game in the mid-1960s – making money right and left, buying, selling, driving and even racing flash cars. He inspired me because it was so clear that he didn’t just do the selling because of the money. It was also for the challenge and the thrill of the game. He always liked to see just how much he could get away with.

He taught me that you don’t get much if you don’t gamble and you don’t get anything if you don’t ask. Throughout my school days my father and I were a great combination at work. No, I wasn’t exactly cut out to be a mechanic in his garage. But I happily tried to drum up extra business elsewhere.

‘Don’t drink and drive. But take a drink home from us.’ That was the snappy advertising slogan I came up with for the local paper when we offered a free bottle of champagne on every car we sold for more than £150. And because our lodger Jock was still working in his wine shop I got a deal on the bubbly as well.

The wheeler-dealer in me was out. I’ve loved a bargain ever since. And I’ve never lost my taste for champagne. The tragedy for my poor father was that, like so many small businesses, his was killed off when VAT was introduced in the 1970s. Funny how life goes. My career was just about taking off at that point. My father was on the edge of bankruptcy. After so many years of being lent and given cars by him, I had just bought one of my own. I remember driving down to Salisbury to show it off. ‘Dad, it’s yours,’ I said, handing over the keys and taking the train back to town.

It was Mrs Christian who pointed me in the right direction when I left school. Over the years we had read so many play texts in our elocution, drama and English lessons. We had talked so much about all the great actors and the wonders of the stage. She gave me the confidence to believe that I too could become a professional actor.

So after one final chat with her I went to the only place I could think of to look for work: the Salisbury Playhouse.

It wasn’t an easy visit.

I had been to see plays there many times with the school and my family. And every time the lady in the box office had terrified me. Her name was Pauline Aston and she was a big, imposing lady, with heavily dyed hair piled up high on top of her head. To me she was a dragon, though like most people who have scared me throughout my life she ended up a close friend and a wonderful person. Her husband, Stan, the cantankerous but wonderful electrician, handyman and stage manager, scared me too – but we ended up getting on like a house on fire.

‘Please don’t let the dragon be there. Please don’t let the dragon be there,’ I mumbled to myself as I walked up to the theatre. The dragon was there.

‘Can I see Mr Salzberk,’ I said, mispronouncing the theatre manager Mr Salsberg’s name because I was so nervous.

‘Wait over there,’ the dragon said, clearly unimpressed, and pointed to a bench on the other side of the theatre foyer.

But for some reason I hadn’t understood exactly where she meant. And I was too scared to risk her wrath by asking again. So I waited, for more than an hour, on the other side of a wall in completely the wrong place. When I ventured out, who should I find but Mr Salsberg, who, bless him, was still looking for me.

‘I want to be an actor,’ I blurted out. Six incoherent words. Not even a ‘hello’ or a ‘how do you do?’ I was the nervous little boy from nowhere. The boy who knew no one and nothing. Mr Salsberg should have laughed me out of town. Instead he looked me up and down and gave me my in.

‘Well, I’m doing She Stoops To Conquer. You can come to that.’ Two sentences in the man’s lovely, low nasal voice. It was enough. It proved that if you don’t ask you don’t get. As usual, I thank my wheeler-dealer father for giving me the confidence to learn that lesson.

As I left the theatre I wasn’t quite sure what the manager had meant. Was this a part in a play? Was I just being asked along to watch? Or was it a job? When I turned up at the theatre the next day I found it was the latter. I was in. There is a small comedy role as a servant in She Stoops To Conquer. It was mine. In truth, it was just a glorified walk-on part. But it did have a few lines. And that was enough. I was on my way. Within a few weeks I had signed a proper contract with the Playhouse. I started out on £2 a week as a student assistant stage manager. I would stay there for two years. It was just the most wonderful period of my life.

The theatre was on Fisherton Street near the river and the railway station. In truth, it wasn’t a real theatre at all. The building used to be a Methodist hall, then something else, until finally it was turned into a theatre with a proper stage and seating. I’d been in the audience a few times with my parents and on school trips. I’d always adored the glamour of the lights, the thick velvet curtains, the plush carpets and all the trappings of theatre. I had also always dreamed that to go backstage would be like going to some kind of Narnia. And so it was – only in reverse.

‘Mind that!’

‘Careful!’

‘Coming through!’

It was chaos. Backstage certainly wasn’t quite the magical world of glamour and beauty that I had imagined. Salisbury Rep was falling apart. There was a tiny set of different stairs and rooms and corridors but there was nowhere to pick up a cat, let alone swing one. And yes, there was the high, intoxicatingly rich scent of make-up and hair spray. But there was also the smell of mould, mildew and damp. The roof leaked all over and most of the buckets were used to protect the seats in the auditorium. Backstage water just drained away wherever it could. Water soaked into almost everything and, however much heat our big old radiators banged out, it was never enough to dry it all out. Backstage the light bulbs died and weren’t always replaced. Old sets, old costumes, long-forgotten props piled up in corridors and corners. Who knows what crawled among them. But who cared?

I always thought of that recruitment scene in Oh! What A Lovely War when the prospective soldiers are mesmerised by the radiant image of Maggie Smith. They all rush forward and find that when they got up close and personal she was a hideous, ravaged old hag. Salisbury Rep was my Maggie Smith. I rushed towards her with all the passion and idealism of youth. But I never ran away again when I saw the ugly truth. I loved her close up just as I had loved her from afar. I wasn’t going to let a little bit of reality get in my way. I never have. It was clear from day one at Salisbury that I was so much younger than everyone else in the company. But for me, of all people, that wasn’t a problem. I’d been around older people all my life. It suited me.

So did my role. As a student assistant stage manager, I was everyone’s general dogsbody. I helped research, track down and collect the props. I was on the book, ready to prompt at each performance. I swept floors, picked up rubbish, even cleaned the toilets in the auditorium. And I barely had time to think. We worked on a fast, tough regime, putting on new plays every second week. Cast, read through, rehearse, perform, repeat. It was relentless. It was intoxicating.

My parents came to most of the shows, especially when I had a role. And we had fun. It was like a little game to see how many items from around their home they would see on stage in each production.

And my magpie tendencies were only one part of my poor mother’s problems. If I wasn’t ‘borrowing’ things for my latest production, Dad was still selling them to make a quick buck and enjoy the fun of the deal. No wonder Mum always had to check before she sat down in her own front room. We’d both take the chair from underneath her given half a chance.

‘Excuse me, son. Do your parents know you’re out in the middle of the night?’

Being stopped by the local bobbies at 2am was another regular part of my new routine. At the end of each play’s short run, I got lumbered with much of the get-in and get-out process. I would start packing up the props and pulling the scenery apart in the wings while the actors were still on stage out front. Then I would put down the screwdrivers and join them for the curtain call before getting on with the job. Most times the clear-up took well into the early hours, hence my moonlit walks home.

What an innocent age that those walks should attract the attention of the police. How grown-up I felt when I told them about my job.

‘I work in the theatre,’ I would say. What a wonderful phrase. I wasn’t even 17 but I had already found my calling.

At the Rep I wasn’t just learning how to put on plays. I was getting a master class in the whole theatrical experience. I loved it. Lesson one came when our passionate stage manager, Jan Booth, told me off for the way I had addressed our star, the marvellous Stephanie Cole, who is a dear friend to this day.

‘Here’s your script, Stephanie,’ I had said as I bounded on to the stage.

‘It’s Miss Cole to you,’ Jan told me in a fierce whisper afterwards. And so it was – at least during working hours. I liked the hierarchy. I could see that luvviness only lasts so long. Being in rep taught me that theatre is a business and that, if something goes wrong, backstage or on stage, then someone has to be held accountable. Everyone needs to know what their roles and responsibilities are.

Unfortunately, I didn’t always get to grips with all of mine.

One of our early plays was a murder mystery set in deepest Devon. When the curtain rose, the first thing the audience heard was a carriage clock (from my parents’ house) strike midnight. The second thing they should have heard was the ringing of a phone. I was on props one night and was watching from the wings as the sole actor on stage listened to the clock and then froze. I froze with him. I had forgotten to put the phone on the table. And I had absolutely no idea what to do about it.

Once again Jan showed me the way.

She picked up the phone from the top of a pile of boxes backstage, walked to the back of the set and knocked on the door.

‘Who is it?’ our lead actor asked, with no idea what might be coming next.

‘I’m here to install your telephone,’ replied Jan.

‘Do come in.’

‘I’ll put it here.’ On stage, in her ordinary clothes, Jan walked to the table, placed the phone on top, tucked the wire under the carpet and turned to leave.

‘Goodnight, sir.’

‘Goodnight.’

Then the phone rang and the play began. What class.

Fortunately I wasn’t the only one to mess up occasionally. Dear Jane Quy, one of our assistant stage managers, was ‘on the book’ in my place one night. For us this meant raising and lowering the curtain as well as being ready to prompt. It’s not the most exciting job in the business, so you really need a hobby to help pass the time. Jane’s hobby was to knit. She was a champion knitter and would work away – fortunately in total silence – while the performance went on to her left. She never once missed her place in the script.

But it did all go wrong one night when she was finishing a stitch as the end of the first act approached. Her knitting, her needles and two balls of bright-green wool all got caught in the curtain’s pulley system. For some reason this short-circuited the whole contraption. The curtain itself barely moved. But Jane’s colourful knitting made a slow procession all the way around our makeshift proscenium arch and all the way back again.

It got us the biggest round of applause of the night.

I don’t think I could have stayed an actor for the next 50 years if I hadn’t had that grounding backstage in Salisbury. I don’t think my love affair with theatre would have survived if I hadn’t seen all its warts from the start. But at the time the props, the curtains and the book weren’t enough.

I wanted to learn how to act. And fortunately I was in very good company. Stephanie – sorry, Miss Cole – was an inspiration. I would watch her in rehearsal, and from the wings in a performance. She could grab an audience. She made bad writing sound good. And, oh God, did she make us all laugh.

She became a true pal, despite her lofty position at the top of the Salisbury tree. I think I first fell in love with her when she was in rehearsal for Mrs Hardcastle in that first production of She Stoops To Conquer when I was still a nervous little new boy in the company. She had to go down three steps while reciting three key lines. But that first rehearsal she tripped. ‘Oh, f**k, c**t, shit,’ she spluttered as she tried to regain her balance. I was such a little baby I barely knew what the words meant. I certainly didn’t know that a woman could use them.

But I think I realised that Stephanie would be great company in the years ahead. I was certainly right about that.

Stephanie wasn’t my only teacher, of course. Oliver Gordon, the Rep’s director, gave me some tough love lessons from the start. His message was pretty simple: ‘Don’t muck about. Go on stage left, say your lines, then piss off stage right.’ That was pretty much the way he saw it. In rep there was no faffing around, no rocket science and no method-acting silliness. Oliver’s message was that if you’re good you get re-hired. If not, try working in a shop. It was sink or swim. Oliver was a real Arthur Askey type and he was also a perfect pantomime dame. His Widow Twankey in Aladdin was a template of mine for years. And we were such a close, tight ship in Salisbury. Oliver’s brother wrote lots of our pantomimes, was married to Stephanie and was another big influence on me.

Everything we did in Salisbury was on a shoestring, but the audiences would never have known it. If she had been asked, I swear that our wardrobe mistress, Barbara Wilson, could quite literally have made a silk purse out of a sow’s ear. In fact, she could probably have made six. We pulled together and it all felt fantastic. For me, the lonely boy who had always felt just a little bit different, it was a revelation. I was in the world I had dreamed of. I was in my element.

For pretty much the only time in my life I also felt as if I was in the money. My £2 a week was pretty paltry. But I was living at home and in my second year at Salisbury my wage rose to £8 a week. After a few more months I hit £12 a week when I was made a full stage manager, while still living at home and paying next to nothing to my parents. Dad’s garages were all doing well and he was always giving me cars and vans to drive. Life was just wonderful.

Staying at home protected me from a lot. It stopped me from growing up too fast and from getting into trouble. But it didn’t entirely shield me from reality.

My sexuality was still pretty much a mystery to me in the late 1960s. I wasn’t in denial and I wasn’t tortured by any sort of sexual angst. I simply had too many other things whizzing around my mind to think about that side of life. But it seemed that plenty of people were prepared to think about it for me.

The wonderfully outrageous Raymond Bowers was clearly one of them. ‘There’s that Christopher Biggins. He’s so queer he could be a lesbian,’ he roared out above the crowd as I walked into the coffee shop at the Playhouse one afternoon. Robin Ellis, who would one day be Ross Poldark to my Reverend Ossie Whitworth, was in the coffee shop with Ralph Watson and his girlfriend Caroline Moody, who died so tragically young. The whole room seemed to fall about laughing at Raymond’s words. I blushed so deeply I nearly fainted. Queer? Lesbian? I didn’t know what any of the words meant, let alone understand the overall sentiment.

But, public embarrassment aside, Raymond turned from someone who could – and indeed did – scare me, into a close pal. He also proved to be a useful role model in an age when visibly gay people seemed few and far between. He lived in The Close in Salisbury with a chic older man called Geoffrey Larkin. Their big town house had a room painted entirely in yellow and contained nothing but a black grand piano. I thought it was the peak of sophistication. Maybe it was.

Raymond and Geoffrey upgraded Great-Aunt Vi’s table manners for me. Serviettes became napkins and the living room itself became a drawing room. The pair were top-notch entertainers and threw the most wonderful dinner parties – or was I supposed to call them supper parties? I forget. Either way I would head home from the events reeling that such stylish and elegant people existed, let alone existed in Salisbury. I was just thrilled to be part of that world. While Geoffrey has sadly died, Raymond is still very much here, working at the National Theatre. I still smile every time I think of him.

Back at the theatre we put on so many productions. We had so many different directors, who all taught me new skills. I was 17 ½ when I got my Equity card, which was essential back then. It was only a simple piece of cardboard. There was no photograph on it and it wasn’t even laminated. But it had my vital Equity number. It was easily the most precious object I had ever owned. After two amazing years I felt I was doing all the right things. But was I learning enough? Was I going in the right direction?

‘You need to go to drama school,’ said Stephanie one day – and I do hope that she meant it in a nice way.

‘You mean in London?’

Something about that scared me. I was too young. Too confused about who I was.

‘It doesn’t have to be there. You should try the Bristol Old Vic Theatre School. They’re as good as anywhere in London but you won’t be distracted by being in the big city and we’ll still be able to see you. Try Bristol,’ she said.

And so I did. But would I get in?

‘Auditions will take place over the course of a weekend and you should be prepared to take part in a variety of exercises throughout your time with us.’ I was floored by the first word of the instruction on the application form and don’t think I ever made it to the end of the page. Auditions? Plural? These would be the first formal auditions I had ever done. A weekend of them would be a little different to collaring dear Mr Salsberg in the foyer of his theatre and saying I wanted to join his company. I feared auditions back then and I loathe them to this day. Do they ever really work? Can’t you spend years perfecting one four-minute piece but be lousy at everything else you are called upon to do? Maybe that’s why Bristol did ask so much more of us all.

Over the two-day assessment we all danced, sang, did our key audition piece and any number of other readings. Six or seven of the theatre school’s people were watching us all the time, scratching things down on note pads, building up the tension with each stroke of the pen. I think it was the first time I’d ever been really nervous. My subconscious must have known how important this was. But after a few weeks of agony I got the acceptance letter. I’d made it past dozens of other keen candidates. I was on my way.

‘I will never, ever experience anything as good as this again.’ Excuse the drama, but that was what I felt. It was what I kept saying, through a ridiculous amount of tears, when I said my goodbyes at an end-of-season party at Salisbury Rep. I remember a few moments when everyone else left me alone in the back of the stalls – a sensible move on their part. I looked around. Yes, it was only a converted church hall. It wasn’t the West End, it wasn’t Broadway. But it had been so good to me.

I would even miss the damp and the smell of all the mildew. I blubbered so much that night I probably added quite a bit to the problem. I left my mark on that place in tears, if nothing else.

But more seriously I was right about it being the end of an era. Actors starting out today miss out enormously now that the old repertory system has passed. I needed that place where I learned so much from other people’s experience. I needed a refuge where I could fall in love with drama. Putting on a new show every few weeks isn’t for the faint-hearted. It’s a hard slog. But it’s worth it. In Salisbury I found out that in the theatre anything can happen, and it usually does. A bit like my life, as I had just discovered.