Читать книгу Istanbul, City of the Fearless - Christopher Houston - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1

Spatial Politics,

Historiography, Method

Introduction

Bu şehirde ölmek yeni birşey değil elbet

Sanki yaşamak daha büyük bir marifet!

(Ha, to die in this city brings no new thrill, Living is a much finer skill!)

—CAN YÜCEL (2005), “Yesenin’den Intihar Pusulası Moskova’dan”

1.1 URBAN ACTIVISM IN ISTANBUL

Imagine a city characterized by the radicalization en masse of students, workers, and professional associations. Imagine as a core aspect of struggle their inventive fabrication of a suite of urban spatial tactics, including militant confrontation over control and use of the city’s public spaces, shantytowns, educational institutions, and sites of production. Sounds and fury, fierceness and fearlessness. Picture a battle for resources, as well as for less quantifiable social goods: rights, authority, and senses of place. Consider one spatial outcome of this mobilization—a city tenuously segregated on left/right and on left/left divisions in nearly all arenas of public social interaction, from universities and high schools to coffee houses, factories, streets, and suburbs. Even the police are fractured into political groups, with one or another of the factions dominant in neighborhood stations. Over time, escalating industrial action by trade unions, and increasing violence in the city’s edge suburbs change activists’ perceptions of urban place. Here is a city precariously balanced between rival political forces and poised between different possible futures, even as its inhabitants charge into urban confrontation and polarization.

Imagine a military insurrection. Total curfew. Flights in and out of the country suspended, a ban on theater and cultural activities, schools and universities shut down. Removing books from library shelves that the new regime might find suspicious. “Wanted” posters pasted at ferry terminals, civil police watching for suspicious responses. Whole suburbs targeted for “special treatment.” Mass arrests and torture, random identity checks in public places, the sudden cutting of roads by police and the searching of buses, assaults on the houses of activists, summary executions. Martial law turning the city into another country. “It was as if time stood still,” said Ömer (Türkiye İsçi Partisi, or Workers Party of Turkey)1 Imagine for hundreds of thousands of people fear of arrest seeping into consciousness, a fear of torture, and of telling under torture when they had a rendezvous or where they had last visited an organization house. Picture body habits changing overnight, in anticipation of future regulations of the junta. Shaving your head in order to stay at the university (Vassaf 2011: 5). “I didn’t go out much in those years,” said one activist.

The city is Istanbul in the years 1974–1983. For militants,2 what is it like to dwell there? How do they transform its places and mood, and respond to others’ remaking of its affective atmospheres and spaces? What of the urban environment itself, synesthetically known by the “whole body sensing and moving” (Casey 1996: 18): how does it sound, feel, smell, and appear? And what of the decades since then, forgetting and remembering it, your activism and its small part in the making of the city’s chaos? Snatch of a song, rhythm of a chanted slogan, anniversary of the death of a comrade, son, or friend. Each live on in the museum of the mind, in the pains of the body, in the affect exuded by objects and photos, and in the intersubjective imagination of daughters and sons who listen to your stories.

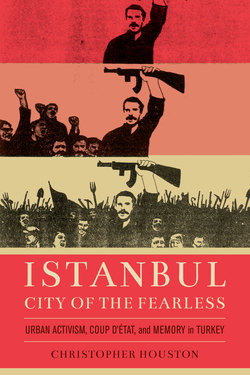

Istanbul, City of the Fearless is a study of urban activism in those years, ruptured by the 1980 military coup d’état—12 Eylül (12 September) in the political vernacular—that brought a decade-long, fragmented social struggle to a bloody close and instituted nearly three years of martial law. Military dogma has it that the coup’s precipitating cause was the “terrorist” actions of urban militants and the anarchical state of the city. In response the junta’s new dispensation instituted in the authoritarian 1982 Constitution was designed to prevent their recrudescence in the politics of the present ever after. The third military intervention in Turkey’s Republican history, 12 Eylül led to the replacement of the liberal 1961 Constitution by one demonstrably less democratic. Loyalty to the ideology of Atatürk was declared the sole guiding principle of the Turkish state and society, with no protection afforded “to thoughts or opinions contrary to . . . the nationalism, principles, reforms and modernism of Atatürk” (Constitution of the Turkish Republic 1982). Civil society associations and political parties alike had to show allegiance to these defining characteristics or face prosecution by the Constitutional Court.

Today the institutions of military tutelage remain in place, from the National Security Council to the Higher Education Council, despite the pressure for constitutional change that has partially characterized Turkish politics over the last decade and a half. As much as in the bodies and memories of a generation, 12 Eylül endures in such political instruments, conditioning contemporary Turkish social life, reason enough to learn more about the period that gave it birth. Its ongoing influence in politics means that this book is simultaneously an anthropological study of the recent past and of the present, of how two significant urban events—the spatial activism of revolutionary movements in the 1970s, and the 1980 coup d’état—not only transformed Istanbul in those years but also exerted their force and influence into the future, becoming sources of novel spatial arrangements, new social divisions, and of inhabitants’ altered perceptions and memories of the city.

In the years immediately before the 1980 military coup Istanbul was experienced as a city in crisis, described by activists as “electric,” “chaotic,” or “strained.” For Ertuğrul, it was “tense, like a family used to violence and waiting for it to happen” (Devrimci Yol [hereafter Dev-Yol, Revolutionary Path/Way]). Others remembered its sounds as raucous and threatening. Activists’ perception of the partisan, fragmented, and unstable qualities of the city reflects a period in which their own actions inflicted a radical contingency upon its spatial organization and order of places. Conventions of engagement, movement, and relationship, partially fostered by material arrangements, were replaced by an uncertainty about the “spatial economy” of places (Lefebvre 1991: 56). For Istanbul’s strongly ideological activists, the stress of the city meant sense and sensibility became acutely attuned to the semiotics of different political fractions, to the behavior of groups of people and to political signs encoded in the urban environment. A rapidly accumulating (and changing) spatial knowledge about when to move around the city, where not to go, how to sit in the coffeehouse, and who to avoid became a potentially life-and-death practice of urban living.3 Recognizing the political alignment of others as communicated through their bodies was critical. Paying attention to the acoustic cues resounding in public space—say to the singing of certain songs on the ferry by a group of people—might save one from a beating.

Activists’ embodied sensory experience of the city, their changing urban knowledge and emerging sense of place were intimately related to political practices of organizing, mobilizing and agitating. Perceptions of Istanbul derived from activists’ purposive attitude toward the city, oriented by the “task” of revolution. Walls were noticed for the possibilities they afforded posters and graffiti, reverberant streets for the cascading of sonic amplification. Squares were assessed for the concatenating choreography of gestures and slogans, the time between train stations for the shaping of a “shock” speech. Yet because activists were dispersed among rival groups, the affordances furnished by the urban environment were sometimes formally divided up between groups and sometimes fought over, adding affective registers of amity and enmity to their experiences of the city. Differences between leftist groups concerning Turkey’s situation spilled over into conflict between fractions, contributing to militants’ feelings of living in an intensely stressed and merciless city.

In brief, in the second half of the 1970s the activists of the socialist factions and the cadres of the ultranationalists together sought both to control and to remake the city, in the process changing radically the experiences and practices of place-making for their own members and for the rest of the city’s inhabitants. Their combat in, with, and over the city, their taking possession of its public spaces and institutions through occupying force, and their attempted creation of politically autonomous zones of self-governance in the city’s deprived shanty-towns were significant strategies in their appropriation, occupation, and transformation of space. The description and analysis of activists’ experiences connect to other matters that I discuss in this book. These include the city’s political geography and its key sites of conflict and mobilization; violence as both spatial practice and generator of urban space; militants’ perceptions of political fractions and of political ideologies; the junta’s post-coup strategies for urban pacification; contrasts in the socio-material structure and spatial organization of Istanbul before and after the coup; and the significance of activist practices and the coup for understanding the neoliberal “globalization” of Istanbul in the decades after.

Spatial Politics

Although this book’s first concern is the perception of urban activists in Istanbul, the larger context of their experience of the city involves their participation in spatial politics, an under-theorized subject for these critical years. By spatial politics here I mean the generation and transformation of space–both symbolic and physical–by a range of social actors, including legal and illegal organizations, the State, the junta, businesses and property developers, private builders, urban designers, and ordinary residents. I use it to include political factions’ appropriation and transformation of the city’s expanding buildings, streets, and institutions, as well as their gaining control of an area and defending and changing it in conformity with, in disregard of, or in opposition to the intentions of its authorities, builders, or other factions. The junta, as “architects” of the coup, pursued spatial politics too, intentionally orchestrating the sound, appearance, and uses of the city.

On both a more concrete and macro level, the spatial politics of earlier eras in urban Turkey have been well studied, most thoroughly in Sibel Bozdoğan’s (2001) work on the architectural culture, design, and buildings of the Republican state in the single-party period (1923–1950). Although the new monumental and modernist architecture that Bozdoğan analyzes in 1930s Ankara was only patchily present in Istanbul, it too was transformed in those very same years. In it the primary endeavor of Turkey’s first Kemalists was not to construct or reassemble Istanbul’s built environment but to disassemble its population, their nationalist program targeting Greeks, Armenians, and Jews for expulsion from the city while Turkifying its economy (Aktar 2000). The result was de-peopled places and displaced people (see chapter 3).

Urban planning, too, has continually remade Istanbul over the Republican period, first in the work of famed urbanist Henri Prost, author of the master plan for the city in 1937 and its chief planner between the years 1936–1951 (Pilsel and Pinon 2010), and then in the substantial transformation of Istanbul by the Democrat Party in the years 1950–1960, led by Prime Minister Adnan Menderes. Murat Gül’s The Making of Modern Istanbul (2009) focuses on the urban development of the city in the 1950s, including the chiseling out of its major thoroughfares—for example Aksaray Caddesi, Beşiktaş Meydanı, Vatan, and Millet Caddeleri or Tarlabaşı Bulvarı—that still give the older parts of the city much of their skeletal form. Yet his book has the same bias as Bozdoğan’s, concentrating on the emerging structure of the city—what Gül calls its morphology—and not on its inhabitants in relation to it.

Compelling as both these analyses are, they are circumscribed by their focus of study, concerned as they are for only half of what Bernard Tschumi (1994) has described as the “violence of architecture.” By this Tschumi means not only the “violence” inflicted upon inhabitants by the material and symbolic arrangements of architecture and urban structure, but also a second dimension: users’ “violence” against places themselves in their transformation—temporary or permanent, authorized or transgressive—of the built environment. For Tschumi, the violence of architecture is not just a metaphor, given the reality of certain sites that destroy emotional and bodily integrity—for example, in the spatialized brutality of prisons and of their soul-shredding sonic design (see chapter 7), or the construction of buildings over and out of the ruins of others.

Yet as metaphor, too, the violence of architecture captures the intensity of relations between buildings-spaces and their users: the ever-present reciprocal and frictional confrontation in which buildings qualify actions, just as actions qualify buildings (Tschumi 1994: 122). The metaphor can be expanded as well, illuminating how buildings redefine, diminish, and highlight other buildings, and how users’ actions impinge upon—rub up against—the actions of other users. Once we include both the planned and unplanned sonic/heard, olfactory/smelt, and textured/felt dimensions of the built environment in our analysis, the tracing of users’ violent engagement with Istanbul’s assemblages of urban space and with each other becomes a task in which the multisensory nature of the city and of the human body need to be taken into account.

My focus on activists’ social construction of space in Istanbul is not, then, in the main concerned with the political intentions embedded in planning interventions and architectural sites in the city, as many recent studies on the built environments of Istanbul, Ankara, and Izmir have been (Holod and Evin 1984, Yeşilkaya 1999, Kolluoğlu-Kırlı 2002, Çelik 2007, Bertram 2008). Nor does it concentrate on the city’s spatial formation as generated by the social relations of the capitalist mode of production (e.g., Keyder 1999), although I do write about both of these processes in chapter 3. Rather, it foregrounds the second dimension of the violence of architecture, in an attempt to bring the vital social movements of the late 1970s, the activists of the leftist factions and the cadres of the ultranationalists, into relationship with the historically evolving spatial organization and built environments of the city. Together they changed radically the experience of inhabiting Istanbul, both for their own partisans and for any politically neutral public.

1.2 ISTANBUL 1974–1983

Why arrow in on the period 1974–1983? Is there not artificiality in bracketing off these years from the influence of earlier social processes and events that bequeathed to activists already-instituted imaginaries, heroes, political practices, and urban environments, even as they sought to create insurgent social-historical habits and arrangements? Despite this risk, 1974 seems to herald the emergence of a city qualitatively different from the Istanbul of the early 1970s. The coalition cobbled together by Süleyman Demirel to form Milliyetçi Cephe, the first “Nationalist Front” government in April 1975, included the “fascist” Milliyetçi Hareket Partisi (MHP [Nationalist Movement Party]), which was given two ministries despite having won only three seats in the five-hundred-member parliament.4 (In the 1977 election the MHP polled 7 percent of the votes and increased their seats in parliament to seventeen.) Ministers enabled the “infiltration” and “pillaging” of state institutions by their own party members, as well as turning a blind eye to the organized “Turkist” violence that began to characterize urban places. Less than a year earlier, in July 1974, an amnesty extended to political activists by the short-lived Ecevit coalition government released thousands of leftist intellectuals, trade unionists, student leaders, and journalists imprisoned after the March 12, 1971, military intervention and declaration of martial law (including the poet Can Yücel).

The Istanbul many returned to had changed. For example, according to Hüseyin (TKP, Turkish Communist Party) until the early 1970s “Istanbul ferries and train were divided into two sections, first and second class. But even if you had the money you couldn’t enter first class unless you were known. Ecevit abolished this in 1973.” The most liberal constitution in the Republic’s history (in 1961) had legalized the establishment of class-based parties, and by 1965 the Workers Party of Turkey had emerged as an electoral force. Its internal fragmenting in the late 1960s, and then its being closed down after the 1971 intervention for (among other things) its recognition of Kurdish rights at its fourth congress in 1970, boosted the appeal of more revolutionary ideologies, and by the mid-1970s a host of radical socialist, communist and anti-imperialist groups were active in the city. These legal and illegal leftist parties and organizations sought to mobilize the inhabitants of the workers’ suburbs on the edges of a rapidly expanding Istanbul, and all over the city their university and even high-school youth groups were active in educating students in their analyses of Turkey’s retarded social development. At the same time, labor militancy was growing among workers in state industries and in large private factory plants, with membership in unions fractured between two major rival confederations, DİSK (Confederation of Revolutionary Trade Unions) and Türk-İş (Confederation of Turkish Trade Unions). That same 1961 constitution (and then more fully Ecevit government policy in 1974) had given unions the right to educate workers upon the signing of a collective agreement; paid leave was funded by the employer. These privileges encouraged union activities, and by 1979 more than one million workers were organized in unions, the majority of them in Istanbul (Mello 2010).

A broad and eclectic range of civil society associations, parties, and organizations had also organized to oppose the Demirel coalition. According to Faik (Aydınlık [Enlightenment]), “When I came out of prison in 1974, I was surprised by the strength of the leftist groups. They were everywhere and very lively.” They had also become more factionalized: “The new TKP began to organize in 1973/4 as well, and had become influential. They gained control of DİSK. After the mid-70s the left groups divided into two fronts [cephe], Maoists and the Soviet aligned groups.” Of course, an active and heavily factionalized radical leftist movement generated its own opposition, not only in employers’ federations or in right-wing political parties vying for parliamentary domination, but also in the form of a para-military anti-communist organization, known as the “idealists” (ülkücüler), whose intention was to combat, violently or otherwise, the influence of the left (Çağlar 1990).

Another momentous event happened in late 1974: the first killing of a student since 1971. “I even remember his name,” said Ömer (Birikim journal), “it was Şahin Aydın. He was stabbed to death by fascists outside a dispensary on Barbaros Boulevard.” Around this time guns, too, became a feature of activist life: “All groups began to be armed after 1975–76, because of the violent anti-union attacks,” said Erdoğan (Dev-Yol). Thus, activists encountered a new experience of urban life—the visceral phenomenon of violence. The bloodshed at the May Day rally of 1977 confirmed a new level of political polarization and provocation had been reached:

I left Halk Kurtuluş [HK: Peoples Liberation] a few days before 1 May 1977, because I could see what they were planning to do, and I thought it was opening everything up to provocation. They were going to march into Taksim Square with guns, hoping for a fight [to avenge a death]. There was a story that someone from TKP had killed a member of HK, and that it was time to take revenge. The TKP and DİSK had already declared that they wouldn’t let Maoist groups enter the square, as they were claiming the workers’ day for themselves. The TKP did not object to Devrimci Yol cadres entering the square. The Dev-Yol militants stayed in front of the Hotel . . . and as they entered someone fired, and then automatic gunfire opened up from Etap Oteli and the waterworks building. (Salih, Kurtuluş [Liberation])

What makes 1983 the end of an era? Post 12 Eylül, the violent pacification of the city continued throughout the years of martial law (see chapter 7). Although the 1982 military constitution structured its working processes, the return to restricted parliamentary authority with the election of Turgut Özal as prime minister in November 1983 signified the cessation of the direct rule of the military junta. Indirect rule was assured through the operation of the new constitution. Kenan Evren remained president of the Republic. Despite this, civilian government facilitated the faint beginnings of a new experience of the city for its cowed and shocked inhabitants. For activists, too, politics began to take on different dimensions:

It is clear that the feminist movement [and human rights] began in 1985 because it was almost the only legal way of doing politics. Thus, the first political march after 12 Eylül was a women’s march from Kadıköy Yoğurtçu Park to Kadıköy Square. Before the march we went out at night to write about the protest and to put slogans on the wall. We went out late as a group, very made-up [çok süslenmiştik]. It was a cold, snowy night, and we caught a taxi from one place to another. The slogan was: “Women exist” [“Kadınlar vardır”]. Unlike the 70s, men could join in the march but only if they stayed silent and marched at the back (Berrin, HK).

Similarly, according to Filiz, the leftist organization Kurtuluş decided in 1985 that if two people with the same experience were to apply for the same position, the woman should be preferred.

In sum, the years 1974–1983 may be construed as constituting a distinct period for the city, characterized first by the fearlessness of mass urban mobilization and then by the fear of mass urban pacification, both of which marked indelibly, in their reckoning with Istanbul, a generation of activists. The years are punctured by the military coup in 1980 that initiated in the city an unprecedented phase of state terror.

Inhabiting Istanbul

How can we gain a preliminary sense of the finer contours of urban living in Istanbul in those years? Certainly the daily newspapers, although politically partisan, illuminate and extend political science and political economy perspectives, facilitating our imagining of the existential affect of the city, of how it was felt/perceived and spoken about, and thus known by its inhabitants. Even details of concrete if apparently random acts of Istanbul’s inhabitants reveal something about the intersubjective relations in which they dwelt—for example, the stealing and cooking of a süs köpeği (small house dog) by two youths because they were hungry (Tercüman, 2 October 1977, p. 5); or the unintended death of a three-year-old girl in Gültepe, killed on her balcony in a fight between two groups by either an “accidental” bullet (kaza kurşun in Cumhuriyet, 11 October), or a “traitor” bullet (hain kurşun in Tercüman, published on the same day).

In 1977 the school term in Istanbul opened with a severe shortage of textbooks and teachers. At one school of fifteen hundred students, packed into a place designed for seven hundred, the students felt it more useful to play football than to sit in classrooms with no teachers (Cumhuriyet, 16 October 1977, p. 7). In the same year, electricity cuts became a feature of daily life; two hours each day rolling out in turn over every district of the city (although never between 12:00 and 1:00 p.m., or on Sundays) (Cumhuriyet, 21 October 1977). Price rises of basic goods in September 1977 brought severe hardship for Istanbul’s poorer inhabitants, and rising school expenses meant that some families sent their children back to the village; many said that they could eat meat only during Bayram holidays. Cumhuriyet (16 October) published the “yoklar listesi” (list of missing goods) reporting which things were unavailable and where—salt in Malatya and Bursa; tüpgaz in Bingöl; mazot in Bitlis; cement in Mardin; wood in Adıyaman.

The list of price rises helps us understand a political campaign announced in Devrimci Yol newspaper on 24 October, bringing Dev-Yol’s supposedly “anarchistic” and “extremist” actions into logical relations with the broader urban condition. “Faşist zülme ve pahalılığa karşı direniş kampanyası’ açtığını bildirmiştir.” (We declare the opening of a resistance campaign against fascist oppression and inflation.) As part of the campaign, a meeting at Sultanahmet Square involved ten democratic organizations protesting against the price hikes. Participants included Halkın Kurtuluşu (People’s Liberation), YDGD (Patriotic Revolutionary Youth Association), İleri Müzik-İş Sendikası (Union of Progressive Music Workers), Perde ve Sahne Sanatçıları Sendikası (Union of Curtain and Theatre Artists), İleri Maden-İş (Progressive Mine Workers), Halk Ozanları (People’s Poets/Minstrels), Kültür Derneği (Culture Association), Yurtsever Devrimci Giyim İşçilleri (Patriotic Revolutionary Textile Workers), Fatih Halk Bilimleri Derneği (Fatih People’s Science Association), Kartal İşçi Derneği (Kartal Worker’s Association), and Gençlik Birliği (Youth Confederation). A group of women and children from Ümraniye’s “1 Mayıs” suburb marched at the front of protesters, carrying posters saying: “There is no water, electricity or school in our gecekondu” (Cumhuriyet, 24 October 1977, p.5).

1.3 HISTORIOGRAPHY OF THE 1970s

There are further reasons, too, for excising and examining these years. For one, over the last three decades there has been little detailed study about urban social movements and the broader practices and perceptions of activists and politically oriented civil society in Istanbul in the second half of the 1970s. Similarly, the lived experiences of activists and the mood of the city during three years of martial law (1980–1983) have rarely been described, nor in that new context have the changed spatial and social relations of its inhabitants. Jenny White notes the existence of a “mass amnesia” about the period, so much so that after 1980 “the violence that had characterized the preceding decade was effaced from public consciousness. No one wished to discuss it, even once the danger of arrest had receded” (White 2002: 41). Indeed, for the period of military dictatorship most political science accounts have focused on the generals’ managed return of government to restricted “civilian rule” as well as on the process of the drafting of a new Constitution, and have been unwilling or uninterested in writing about the perceptions and fate of activists.

This absence of research and lack of public knowledge is even more striking when we consider a subdued yet central understanding of Istanbul that has insinuated itself into the minds of its inhabitants and intellectuals alike: the 1980 military coup marks the great dividing line between the present “globalized” city and what is felt to be a foreign country of the past. For many analysts the 1980 coup d’état and its instituting of the Third Republic ushered in a new era in Turkish politics, a period characterized by the eclipse of previously dominant leftist movements and ideologies, and the emergence of an identity struggle between Islamists and secularists, as well as between pro-Kurdish movements and a bloody-minded State, all in the context of a newly liberalized, consumer-oriented and globalizing economy (e.g., see Houston 2001). Accordingly, most social science investigation of any particular contemporary urban phenomenon places its origin in the short durée of post-coup time.5 More than ever, Istanbul is a polarized and crowded mega-city of inferior apartments, monuments, shopping malls, five-star hotels, and luxury housing developments. Studies of Istanbul’s urban reconfiguration since 1980 have focused on a vast range of subjects, from the rise of gated communities on its urban fringes (Geniş 2007) to studies of gentrification in the older suburbs (Ergun 2004); from exploration of the commodification of its public spaces (Öz and Eder 2012) to investigation of the influence on its secular politics of transnational organizations and of the supra-state project of the EU (Gökarıksel and Mitchell 2005); from tracking of the city’s financial extension beyond Turkey itself (Sassen 2009) to analysis of new forms of social exclusion for the most recent generation of rural or Kurdish migrants to the city (Keyder 2005, Secor 2004). In each of them the coup indexes a formulaic baseline from which the trends of the present might be imagined, measured, and assessed.

Yet despite this widely held local knowledge concerning the defining significance of 12 Eylül as a threshold to a new global city, little research over the last three decades has focused directly on Istanbul and its activists in the critical years immediately before and after the coup. At worst, in some accounts 12 Eylül is barely mentioned, by-passed in the breathless rush to come to terms with neoliberal and global Istanbul. Sassen’s article about Istanbul (2009) is a case in point. According to her paradigmatic sense of the term, Istanbul is now a “global city,” identified by changing sets of numbers that measure its flows of money, people, and ideas. But in her analysis there are no national causes, actors, opponents, or makers of its “globalization,” nor is there a discussion of the city’s actual history apart from that alluded to in the title, its “history” as a place of “eternal intersection.”

Why? Why this local (ac)knowledge(ment) that the military coup in 1980 is the crucial event in the long-term reengineering of the city, alongside an apparently effaced intellectual curiosity and public memory about what it was like to live, organize, agitate, mobilize, and suffer in Istanbul at that time?

One possibility is that the years constitute a collective trauma in the lives of many who lived through them, their excesses perceptually overwhelming and therefore difficult to comprehend. In his introduction to The Making of Modern Turkey Feroz Ahmad notes in a single terse paragraph on the 1970s that “political violence and terrorism, which have yet to be adequately explained, made the lives of most Turks unbearable” (1993: 13). Similarly, in her recent book Muslim Nationalism and the New Turks, Jenny White summarizes the decade in three brief paragraphs, relating how “violence and ideological extremism were inescapable.” She finishes by recounting her relieved escape from the situation: “Having lived through three years of street violence in Ankara, where I was studying at Hacettepe University, I pocketed my master’s degree and left the country in 1978” (2013: 34, 35).

Reflections upon my fieldwork and interviews with ex-activists add something critical to Ahmad and White’s brief “outsider” comments on urban life. True, militants’ accounts of activism in the years before 12 Eylül document their participation in acts of violent militancy, in what Samim described as their “‘liquidation’ of the felt validity of the revolutionary experience of others” (1981: 84). Yet unlike the characters in novels described by Irzık (2010) in her analysis of 1971 coup d’état fiction, who are invariably depicted as persecuted by the State despite their innocence, the activists interviewed for this research did not protest that their victimization as leftists was mutually incompatible with the experiential realities of engaging in democratic and sometimes revolutionary action, including their own acts of violence. Indeed, the interviews revealed something different—the capacity of ex-activists not just to remember their status as combatants in a civil war or as victims of horrifying human rights abuses post coup but also to acknowledge their own flawed agency as political actors.

Perhaps differences in accounts of those years disclose not only insider or outsider perspectives but also contrary existential perceptions? Ahmad and White’s brief comments express a discomforting experience of passivity in the face of the actions and activities of others. By contrast, activists recollect their own sense of social efficacy extended against the friction of other actors. Activism by definition is a mode of embodied agency, and activists felt and hoped that they were remaking the world. Three years of martial law in Istanbul re-tuned the mood of residents in the city, enacting a perception of helplessness, and traumatizing activists and residents alike in the name of Atatürk.

Justifying the Coup d’État

There is more involved in this public and intellectual disengagement from the critical years before and after the coup, alongside any guilt, anger, or fear felt by militants or Istanbul’s inhabitants about what they did or about what was done to them. The minimal comprehension of that period and the lack of public memory about it are demonstrated in the near complete absence of any officially sanctioned visual monuments to its most striking events. There is one moving, albeit unofficial, memorial to Metin Yüksel in the courtyard of Fatih mosque, leading member of the Muslim youth group Akıncılar, who in 1979 was murdered by MHP commandos after attending Friday prayers. His fallen body shape is etched into the paving stones of the mosque courtyard where he was slain. Prayers are still held there annually in his memory. The lack of sites of memory testifies to a suppression of militants’ voices and perceptions and to an ongoing project by Turkish state institutions to obscure or depreciate the full gamut of acivists’ political and social activities.

Most active in this project is the Turkish Armed Forces, which attributes responsibility for the military intervention to the collective anarchism, terrorism, and class separatism of the militants themselves. In his speech broadcast on State TV and Radio on the morning of the coup, General Kenan Evren drew attention to the “perverted ideologies” that made some people sing the “Internationale” in place of the Turkish national anthem. It is plausible to suggest that denigrating the activists of those years comprised a key policy through which the Turkish military legitimized its preeminent role in post-coup politics. This campaign also ensured the immunity from prosecution of the military personnel responsible for the gross human rights abuses carried out as a matter of regime policy after the coup. It was only thirty years after the intervention, with the junta leaders nearly all deceased, that the Turkish parliament abrogated the constitutional clause granting coup leaders amnesty from prosecution (see chapter 8). At the time of writing, tens of civil court cases have been launched against military personnel. The outcomes of these are uncertain.

In brief, a dominant discourse invokes the increasingly violent polity in the years before the coup as its very justification, binding for better or worse militants and coup-makers to each other. That narrative positions the activists of the late 1970s as the city’s fulcrum generation, negatively but causally linked to the restructuring of Istanbul and of Turkey itself. Activists themselves live with that status, rejecting the implication that they deserved their arrest and torture while reflecting upon the failure of their struggle to transform urban society.6 Indeed my interviews with ex-activists reveal how in retrospect they are intensely critical of the faults and shortcomings of their own groups and factions in the years before the coup (see chapters 2, 4, and 5), a critique, in short, of themselves, as well as an imagining of their own partial responsibility for the present flawed development and state of the city. This sober self-examination informs many ex-activists’ identities and practices in the present.

Reference above to a “dominant” discourse suggests that it is insufficient to say that the 1970s have not been written about or analyzed. More precisely, it is the complex and varied modes of activism, including consideration of the diverse practices, motivations, experiences, intentions, and ethics of militants in the urban environment that have been simplified or ignored. By contrast, there is a large literature listing and explaining the context of events leading up to the coup. The best-disseminated account has been the discourse of the junta, broadcast (for years) after the coup in censored media space. Book chapters in general histories of “modern Turkey,” often referencing the picture of the 1970s sketched out by the junta, comprise a second literature, while work oriented to dependency and world-systems theory is a third, analyzing the struggle over the political economy as a significant reason for social conflict.

The junta’s narrative justifying the intervention was repetitive and clear, consistently made in speeches or interviews given by members of the National Security Council in the months after the coup and published in the strictly controlled press. It included the following claims: the armed forces are a disinterested institution sitting above the grubby affairs of politicians, political parties, and partisan civil society, called upon to act for the benefit of the neutral citizens who are disadvantaged by the politicization of state services; indeed the intervention was an obligation forced upon the military as a result of the conditions of its existence, given the duty bestowed upon it by Atatürk to protect and guard the Turkish Republic; it had warned the government and the opposition numerous times to get their house in order, but they had refused to act to solve the biggest “regime crisis” in the history of the Republic; the country was in peril on a number of fronts, particularly from the politicians’ inability or refusal to protect the constitutional and democratic institutions of the state and regime; further, a grave threat was posed by the actions of inside and outside powers who armed, brainwashed, and released militants into the environment, leading to anarchy, terror, and separatism, and to the needless deaths of twenty or more young people each day.

Single chapters in general political histories of modern Turkey comprise a second literature describing the 1970s (see for example Zürcher 1995; Ahmad 1993, 2003; Pope and Pope 1997; Davison 1998; Howard 2001; Kalaycıoğlu 2005; Akşin 2007; Waldman and Calışkan 2017; Ter-Matevosyan 2019). Although they usefully chronologize an incredible array of events—elections, coalitions, prime ministers, galloping inflation, price-hikes for food and oil, balance-of-payment deficits, Cyprus tensions, strikes, acts of violence and assassination, notorious massacres—in the main these chapters lack, paradoxically, both theoretical analysis and description of actors’ concrete experience and perspectives.

Further, the narrative of the junta influences much of their analysis. In more than a few accounts, society is described as threatened by anarchy; activists are reduced to “terrorists” and “extremists” fighting in the streets; and politicians are criticized as incompetent, naive, or frivolous (Gunter 1989, Kalaycıoğlu 2005: 124), and the military—far from being presented as turning a blind eye to or even sponsoring certain perpetrators of urban violence—is portrayed as forced to disinterestedly intervene in society to resolve a social and political crisis for which (it is implied) it had no responsibility in generating, in order to restore the tenets of the Atatürk Cumhuriyeti (Atatürk Republic). To give just one example: in his introduction to Ersin Kalaycıoğlu’s Turkish Dynamics (2005) Barry Rubin writes, “At times, extremists of left and right fought in the streets. As a result, the military—which saw itself as the guardian of Atatürk virtues—repeatedly had to intervene. Yet if the system’s problem was the sporadic coups, its strength was that each one returned the country to a democratic system” (2005: xii). Clearly, the military constitution of 1982 did not return Turkey to a democratic system, at least in any normative sense of the word. Further, in some writings, activist violence is condemned even as the violent imposition of non-violence for “civil” society is condoned (see Gunter 1989 for an egregious justification of torture, while citing the military regime’s own publications after the coup as his chief source of information about “terrorist” events). In some of these accounts the coup is presented as enacting a necessary depoliticization of Turkish society rather than as simultaneously instituting a new political-economic model in its place. For example, in his chapter “The Troubled Years 1967–1987” in Turkey: A Short History (1998: 199), Roderic Davison repeats approvingly the military’s argument that the 1982 constitution restricted the scope of democratic rights to prevent their abuse by those who sought to undermine democratic rights.

More interestingly, certain writers’ assumptions about modernization, including a willingness to populate the binary categories of modernity and tradition with secularists and Islamists (e.g., Kalaycıoğlu 2012: 173), translate as a refusal to acknowledge one occluded but central dimension of the 1970s leftist-rightist ideological struggle: its character as an intra-Ataturkist dispute organized for many rightists and leftists around key Kemalist terms of nationalism/Turkism and anti-imperialism/independence respectively. Accordingly, the threat of “Islamic fundamentalism,” and more specifically a rally held in Konya by the MSP (Milli Selamet Partisi [National Salvation Party) a week before the coup is often cited as another legitimate reason for 12 Eylül (see Zürcher 1995, Gunter 1989, Ahmed 2003).7

Last, in some chapters “Kurdish separatism”—not ethnic Turkish chauvinism—is mentioned as a threatening tendency in south-east Turkey, and presented as a lawful concern in inciting military intervention (see Davison 1998, Howard 2001, Gunter 1989). In his memoirs, Kenan Evren himself claimed that there were eight “separatist” (bölücü) organizations operating in the southeast of Turkey before the coup (in Pope and Pope 1997). In such explanations there is little acknowledgment of the oppressive long-term project of assimilation directed toward Kurds by the Kemalist state, immediately reinforced by the junta’s banning of Kurdish after the coup. Nor is the notorious and extreme violence meted out to Kurdish inmates in Diyarbakır Prison after 12 Eylül much spoken about (see Odabaşı 1991), or the junta’s reorganization in 1981 of Turkish nationalist outlets like the Turkish Historical Society and the Directorate-General of Intelligence and Research, aimed at producing propaganda about ethnic minorities (see chapter 7).

By contrast, for scholars versed in dependency theory and the world-systems school, the crisis of state-led import-substituting industrialization (ISI) in the 1970s determined conditions for conflict over the mode of capital accumulation and its distribution (see for example Gülalp 1997, Keyder 1993). An exemplary study in this vein is Çağlar Keyder’s State and Class in Turkey (1987), which provides both a macroeconomic autopsy of the systemic failure of ISI in the 1970s and an account of its conditioning of political developments, including fragile and fragmented coalition governments, failed populism, intra- and inter-class rivalry and antagonism, and radicalization of a segment of the population alienated from center left and center right parliamentary politics. Keyder sets the crisis in the larger context of the Turkish economy’s incorporation into the world economy and division of labor, arguing that global capitalism provides a “set of constraints within which class struggle at the national level determines specific outcomes” (1987: 4).

In sum, presentation of the political or economic background to activists’ actions and relationships has dominated accounts explaining the years before and after the military intervention, alongside much repetition of the utterances of the makers of the coup. An underlying concern of both the synoptic political science and political economy approaches has been the political implications of the rapid urbanization of Turkey from the 1950s onward, seen most strikingly in the spread of shanty towns in Istanbul outside the boundaries of the historic city (see chapter 3). In the process, either the political-economic interplay between global and local class-actors, dysfunctional urbanization, or the misadventures of a more narrowly defined political system have been foregrounded as the appropriate lens through which to inspect selected features of the decade, as well as to explain activists’ activities. Indeed, economic developments are sometimes presented as the cause as well as the context of activists’ actions, through the assumption that actors’ calculation and pursuit of economic self-interest is the primary factor informing their motivations and decisions.

1.4 METHODOLOGICAL CONSIDERATIONS

I make these points not to overly criticize such analyses, but more importantly to note that none of these approaches asked activists themselves what they thought they were doing, nor placed much value upon describing and analyzing phenomena such as the built environment, militant bodies, movement around the city, places, moods, ethics, violence, ideologies, or factions as perceived and remembered by participants. Even the more thorough discussions (such as Erich Zürcher’s 1995 Turkey: A Modern History) rarely encompass personal narratives, implying that individuals’ lives and experiences are best comprehended by their being aggregated and subsumed within these public, more collective, events. Yet surely the opposite is equally true: an account of the death of a child and its traumatic effect on a family illuminates the significance of infant mortality rates as much as a statistical graph pegging out its comparative percentages (see Pamuk 2014 for a comparison with other countries of Turkey’s declining rates between 1950 and 1980).

Equally curiously, the particularity of Istanbul and of its known, used, and efficacious places or built environments, in relation to which activists’ political passions were stirred and stimulated, seems also to have disappeared in the accounts sketched out above. Yet the built environments and homes of the shantytowns were more than sites of generalized conflict and mobilization, and Istanbul itself more than the “spatial manifestation” (in factories, workshops, and offices) of capital accumulation or political crisis. The city that people grow up in is an inhabited city.8 Writing about these years should also involve learning and revealing how activists heard, saw, felt, used and spoke about the city and its unstable parts, as well as their agonistic relationships with other emplaced inhabitants. Places were known through the senses of the body, and in situational and often-antagonistic relationship to other related places, not through their position on a map or, as in the case of the shantytowns, by their abstract apportioning in time, theorized as existing temporally somewhere between the city and the village.

“There was Kömürlük cafeteria in Aksaray, on the left of Tarlabaşı Bulvarı going toward the Marmara Sea, after the underpass; every group wanted to get control of it. Sometimes Dev-Yol occupied it, sometimes İGD [Progressive Youth Association]” (Ömer, İGD). Ümit remembered the same teahouse slightly differently: “On one side was the İGD Stalinists; on the other side farther down the row were the Maoists. No one ever passed between the groups or places.” Leftists also patronized Turizm Tea Garden in Kadıköy, just as Barboros Café and Mühendisler Kıraathanesi in Beşiktaş were places where leftist students met. Kulluk Kahvesi in Beyazıt was notoriously MHP; and Diriliş Kıraathanesi in Süleymaniye was important for MSP and Akıncı (its youth wing) activists. Places and people were singular, and nomenclature expressed ownership, as well as actual or admired social practices. For example, according to Metiner (2008: 73), Muslim activists named Diriliş coffeehouse after the book Diriliş neslinin amentüsü (Creed of a reborn generation), by the writer and poet Sezai Karakoç.

Steve Feld stresses the affective dimensions of place names: “Because [they] are fundamental to the description and expression of experiential realities, these names are deeply linked to the embodied sensation of places” (1996: 113). After the coup the junta changed May 1st, the Ümraniye shantytown settled and named by its militant residents, to Mustafa Kemal. In the city of a thousand killings it is the name of each dead activist—Şahin Aydın or Metin Yüksel—that makes them particular persons, grieved for by those who knew or loved them.

We will see how else we may gain a sense of the city, and of how it was sensed by its politicized inhabitants, in chapters 2, 4, 5, 6, and 7, as well as in readings from newspapers and other archival material.9 The primary source of this sense of their city is the activists’ own accounts of their emplaced experiences and memories of Istanbul in the years before and after 12 Eylül. Analysis of them attests to activists’ own projects of spatial politics and production. Further, militants’ generation of space occurred not only through their labor in the constructing of roads and houses in politically sympathetic shanty towns, but also in their theatrically embodied gestures, choreographed movements, and noisy exchanges in urban space, and in their symbolic, affective, and imaginative relations with it. This focus on activists’ perceptions, urban knowledge, projects, and place-creation—for example through reverberating revolutionary songs—adds a complementary and much needed empirical dimension to the political economy and political science perspectives, while facilitating a necessary critique of the claims of the junta. It also enables us to learn from practitioners about the practicalities, potentialities, limitations, and pitfalls of urban activism.

Research Practices

Here let me briefly describe the central dimensions of the research process itself. Alongside written sources, the key material analyzed in this book derives from extensive interviews with ex-militants, which sought to facilitate autobiographical reflection upon their earlier selves and actions and upon the city (and its places) that co-constituted them. Over a dispersed period of nearly twelve months in 2009 and 2010, and then more briefly again in 2011, 2013, and 2014, I met with more than fifty people, men and women, from a variety of political organizations, including with militants from the violently anti-communist Nationalist Action Party (MHP). However, as will become clear in the book, there is a discrepancy in interview numbers between leftists and rightists that is reflected in the much greater depth of material on leftist practices, ideologies, activists, and (f)actions. Interviews often ran for two or three hours, and in many cases resulted in follow-up sessions. Interviewees ranged in age from forty-six to fifty-five, and were working in a number of areas, including journalism, television, unions, education, or in their own businesses. Many were still politically active in new associations. Interviewees were storytellers, presenting their versions of events. They were very interested in the perceptions of ex-revolutionaries (devrimciler) in organizations other than their own—a curiosity that was discouraged at the time, given antagonisms between groups. Indeed, one of their concerns was whether this study would do justice to militants’ variety of experiences, given interviewees’ realization of the particularity of the parts of the city they had been familiar with, as well as their intuition of political and socioeconomic differences between militants of different factions.

In the vast majority of cases, interviewees had been youthful members of a number of different organizations or factions from Turkish socialism’s three major branches, the pro-Soviet factions (including the TKP); the Maoist sects (including HK); and more Latin American–inspired nonaligned groups, including Dev-Yol and Devrimci Sol (Revolutionary Left). In fact, over the decade of the 1970s as many as forty-five radical leftist groups were active. Interviewees recalled an intense factionalism and rivalry between leftist organizations for influence and initiative in urban militancy, detailing how certain groups refused joint cause with others, or even fought each other over a killing or an assault (see chapter 6). Violent conflict between leftist factions and between leftists and rightist groups was also connected to struggles over control of place. Official positions in the center of communism (USSR/China) had an effect on Turkish leftists too, with militants describing how political and ideological differences between factions were reinforced by minor nuances in clothing and style.

Despite this, militants’ descriptions of their experiences revealed a common stock of performative spatial tactics shared across nearly all groups, including protests, strikes, sit-ins, revolutionary culture (theater, music), pirate speechmaking (on trains or in the cinema), marking and occupation of places, slum mobilization, organizational separatism, and ready recourse to violence (see chapters 2, 4, 5, and 6). None of these groups, with the exception of the MHP and the PKK (Partiya Kakeren Kurdistane [Kurdistan Workers Party]), exist in the present; although there are renamed organizations that trace their lineage back to the movements of the late 1960s and ’70s.

Istanbul, City of the Fearless is also a study of memories. Even as activists recounted “raw” experience (things as they were or as they happened), in our conversations, both my leading questions and interviewees’ present interests and intentions led them to foreground certain memories of spatial practices and the city and to relegate others to the “fringes” of consciousness. In this reassembling and new contextualizing of past memories, concern over the absolute veracity of activists’ descriptions misses the way that in interviews telling is also a performance, as the literature on the constructive nature of remembering explores (Saunders and Aghaie 2005, Casey 1987). “I’m warmed up now,” said Ulvi (MHP) as we spoke, “everything is fresh in my mind.”

Indeed, in asking activists to attentively describe the sounds, appearances, and textures of the social environment in Istanbul, the interview process facilitated their reimagining of perception, as well as providing an opportunity to reorder memories in the present. “When the image is new, the world is new,” says Bachelard (1994: 47). Careful description of a thing, an emotion or a relationship possesses a generative dimension. As Bachelard muses in The Poetics of Space, “Often when we think we are describing we merely imagine” (120). Equally significantly, ex-partisans’ memories of Istanbul have been dynamically and ceaselessly reconstituted in the relational context of their ongoing engagements with the city’s social and political worlds. As Lambek notes in describing people’s ethical memories, specific incidents are located “within the stream of particular lives and the narratives that are constituted from them, changing its valence in relation to the further unfolding of those lives and narratives and never fully determined or predictable” (2010: 4). In the event of the interview, then, activists were able to engage in an act of “phenomenological modification” (Husserl 1962), taking up new perspectives, attitudes, and feelings toward people and events forgotten or perceived as having little significance at the time. Their new insights into the social relationships of the day have informed my own tentative, more synthetic, analysis.

I count this synthesis as classic ethnography, in that genre’s most literal and basic sense: a crafted description (grapho) about people (ethnos), and more specifically about a class of people distinguished by their practices—activism—and their memories and understandings of Istanbul in the years immediately before and after the coup. Following Basso, we might also aptly call it a study of “lived topography” (Basso 1996: 58). It is ethnography in another sense also. It does not aim, through the empirical material and situation presented, to illuminate or progress any theoretical “problem” confounding or animating current debates within the academy. By contrast I prefer to engage with social theory in a more “micro” fashion—drawing out theoretical implications from activist practice and context, and using theory to illuminate aspects of those practices, while seeking to compose the richness, confusion, and reflexive dimensions of people’s lives. Through these micro-excursions and comments and alongside the ethnography, I intend a “case-study” of phenomenological anthropology to emerge, an example of what a more phenomenology-inclined anthropology might sound and look like.

In short, Istanbul, City of the Fearless is my describing of activists’ own ethnography of the city. Description—by both the activist and the anthropologist—is a complex activity. In his poem “Description without Place,” Wallace Stevens (1990) draws attention to the constituting or compositional nature of description or of accounts of accounts. As he puts it, description is “a little different from reality: / The difference that we make in what we see.” And not just in what we see. As writer of ethnography, description is the difference we make in what we write. Similarly, as phenomenology, the intellectual tradition that most values its enterprise, has long pointed out, the describing, interpreting, or imagining of anything is intimately connected to the consciousness and perceptions—to the intentions—of the describer, even as the describer’s perception is an act mediated by a range of other processes. These include the describer’s own history and prejudgments, including education in a discipline, and the intersubjective encounter of the interview.

Chapter Outline

To compose my descriptions I have divided the book into eight chapters. Chapter 2 identifies certain central themes of phenomenological philosophy that provide City of the Fearless with a suggestive language for apprehending activists’ engagement with and experience of Istanbul. These include phenomenology’s emphasis on human intentionality and its constituting awareness of events, places, and people, and its insights into how the event and pedagogy of activism involved militants in specific perceptual (phenomenological) modifications.

What is the relevant pre-history to 1970s activism? Chapter 3 recounts the history of the “violence of architecture” in Istanbul from the founding of the Turkish Republic in 1923 until the mid-1970s, to give readers some idea of the origins of the city’s key features, which a multitude of political activists in the 1970s sought to control or revolutionize. One core historical process included the Turkish Republic’s unrelenting de-Ottomanization of Istanbul, involving both the regularization of Istanbul through modernist planning, and its Turkification policies targeting its non-Muslim residents for expulsion. Another was the tremendous expansion of the city after the 1950s through rural-urban migration, and the burgeoning of the city’s shantytowns (gecekondu), which became key theaters and crucibles of political conflict. According to Setha Low, “An ethnographic approach to the study of urban space includ[es] four areas of spatial/cultural analysis—historical emergence, sociopolitical and economic structuring, patterns of social use, and [its] experiential meanings” (1996: 400). I distribute discussion of these to various parts of the study, and areas one and two to chapter 3 in particular. In short, what was Istanbul like in 1974, and how did it get to be like that?

Chapters 4 and 5 explore activists’ own production of space in Istanbul. To do so I disaggregate from partisans’ narratives four major modes of politico-spatial practice, including their visual politics, their sonic politics, their occupation of space, and their performance of violence. Chapter 4 concludes by analyzing the content and meaning of factions’ obituaries, and of statements from bereaved families for killed activists published in their newspapers or journals. Chapter 5 continues this exploration of activists’ constitution of the city but arrows in on the political and ethical engagements of militant groups in three particular arenas in Istanbul’s urban geography: in squatter settlements; in factories and workplaces; and in municipalities. Ideological activism in shantytowns, labor activism in factories and unions, and urban activism in Councils were core aspects of one single but bitterly factionalized revolutionary movement. This “interconnectedness” of the sprawling revolutionary enterprise is particularly important given junta claims that their intervention was necessitated by the “terrorism” of activists. Most groups did not pursue armed struggle.

Conflicts between militants, factions, ideologies, and ideologists revolved around two inseparable concerns: in order to make a revolution, what is our situation, and how is this to be done? Chapter 6 attends to a single broad theme with at least two dimensions—activists’ perceptions of their factions, and of their factions’ ideologies. The chapter moves back and forth between two foci: description of how partisans (personally and collectively) constituted or applied ideologies, and exploration of how the political/spatial actions, experiences, and decisions of militants were guided by the varied historical narratives, political claims, and economic models of leftist and rightist ideologies.

Coup d’état! Chapter 7 concentrates on three temporally experienced and interrelated themes. The first describes the junta’s immediate spatial and activist politics after the military insurrection, embarked upon to punish militants and to intimidate and pacify the city. The second involves investigation of activists’ responses to this assault on Istanbul’s urban bodies and places. The third section presents the junta’s legal and institutional reconstruction of Turkish society, intended to drastically and permanently reorganize its political practices. Taken together the themes chronicle Istanbul’s shock entry into a reign of fascism and its preparation for a new authoritarian political and neoliberal economic order. Chapter 8 concludes Istanbul, City of the Fearless by describing some of the ways that ex-activists and others in the present continue to reckon with the meaning of those events. In particular, it shows how acts of urban commemoration by leftist political parties, unions, and civil society groups communicate to younger generations both the aims of their struggle and the losses accruing to its participants.

The following chapter more directly addresses the phenomenological approach that orients the book’s spatial analysis of the city. It affirms that at the crux of a phenomenological account of social life lies the matter of individual perception in any or all of its dimensions—corporeal, interactional, cultivated, political, and collective (Bachelard 1994, Casey 1996, Duranti 2009, Ram and Houston 2015). As people’s orientations to the world change—say, by their living through a significant historical event such as the spatial convulsions wrought by urban militancy, or by a diminution of their bodily capacities by torture—so also do different properties of places, situations, emotions and people, once at the margins of noticing, come into focus. A phenomenological perspective illuminates a number of key social processes germane to understanding Istanbul in those years: activism and its modification of place perception; militants’ frictional fashioning of the affordances of the urban environment; the power of inhabited places through their spatial furnishment by others; songs’, bodies’, places’ and things’ holding of militants’ memories; and the contemporary politics impinging upon the forgetting and remembering of 1970s activism. In doing so Istanbul, City of the Fearless presents not only a social history but also a phenomenological study of political memory and commemoration in the present.

1. I have changed the names of activists, but not the political faction they belonged too, nor their gender. The first time I mention the name of a political group or faction I translate it into English. Thereafter I use the Turkish abbreviation. See the list of names of political organizations.

2. I use activist, militant, and partisan interchangeably in this book to refer to the active members of different political factions.

3. According to Zürcher (1995) in the year before the coup up to twenty people a day were slain in urban conflict.

4. There is an issue with the nomenclature used by protagonists to describe combatants in the political struggle in these years. Fascist is the word used by leftist groups to describe the commandos they were confronted by. The rightists called themselves “idealists,” inspired by the ideals (ülküler) or principles of Turkism. Similarly, the Ülkücü labeled all leftist groups “communists,” despite profound differences between them.

5. Let me give two examples, each from the volume Orienting Istanbul: Cultural Capital of Europe (2010). Çağlar Keyder begins his narrative with a single paragraph on peasant modernization through urban migration to Istanbul in the 1960s and 70s, before proclaiming how “all this changed when Istanbul, in common with other globalizing cities of the Third World after the 1980s, experienced the shock of rapid integration into transnational markets and witnessed the emergence of a new axis of stratification” (2010: 26). Göktürk, Soysal and Türeli’s introduction ignores the 1970s while claiming that “a new phase of urban restructuring begins with economic liberalization in the 1980s” (2010: 3).

6. See the title Bizim çocuklar yapamadı (Our children couldn’t do it) (Mavioğlu 2008), which in retelling the story of 12 Eylül and its aftermath echoes the reported words of the American consul in Ankara to the State Department on the night of the coup: “Our boys have done it.”

7. Kenan Evren specifically mentioned the Konya rally in his address to the press, September 16 1980, citing it as an example of the dangerous publicization of “reactionary” beliefs (2000: 23).

8. Cf. Bachelard: “The house we were born in is an inhabited house” (1994: 14).

9. For example, see the often short lived (and now fading) archived journals of different political factions that analyzed social conditions in the years leading up to the coup and pronounced on both the current situation and the revolutionary strategy or tactics to overcome it.