Читать книгу Your Choice - Christopher Peterka - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Intro

Estimated reading time: 15 minutes in 2 sections

First section: 9 minutes

Second section: 6 minutes HOW LONG WE’LL BE HERE FOR IS UP TO US HELLO

ОглавлениеYou’re awesome.

Seriously: even without recording yourself as you do a backflip through a hoop and getting the clip included in a YouTube compilation, you’re already an extraordinary creature. Your body is beautiful: it’s a finely tuned organism that is exceptionally adaptable to its environment; and long before you’ve put it to any use, your brain is the most complex thing known to humankind. You are genuinely amazing.

But you’re also a Dumb Fuck.

You’re a Dumb Fuck because you trust Mark Zuckerberg with your data. And it’s not us calling you a Dumb Fuck, it’s Mark Zuckerberg himself: he calls us all Dumb Fucks, and he’s right: we’re all Dumb Fucks for trusting him with our data.

If you’re one of the few people who don’t, and you don’t have a Facebook account, or you don’t use it, then congratulations. Just don’t celebrate too soon: if you trust any of the big digital players anywhere in the world with your data, you’re giving yourself away.

[YOU ARE WARE. DISPOSABLE, EXPLOITABLE, SELLABLE.]

You’re giving away everything there is to know about you: you are ware. Disposable, exploitable, sellable. And they do sell you. To their advertisers, to each other, mostly though back to you: they get to know you so well that they can not only sell you the things you want, they can easily make you want the things they sell. They can make you believe things you never thought could be true, and they can make you doubt what you always took for granted. They own you.

And yet: don’t beat yourself up too much about this either. Because you may not have much choice. You’re living in a world where very soon there will be perhaps seven or eight digital ›superstates‹ that control every significant transaction any of us are ever likely to conduct.

Social media was just the start. China is on a trajectory where your social profile and public conduct is directly linked to your bank account and your ability to travel. Your physical life and your online existence are tightly meshed together. If you cross the street in Shenzhen when the red man is showing and the face recognition software captures you, you don’t even get sent a fine: the money is taken from your account automatically, and your social credit is docked. And while you still glance at the wallet on your smartphone in consternation, everybody around you is staring at the big roadside screen, which shows the world your face and shames you for having gone against the ›common good‹…

And don’t think for one moment that this isn’t happening or couldn’t happen elsewhere. ›Staying offline‹ or ›opting out of social media‹ are no longer going to be available as options. You may not be a Dumb Fuck and blindly trust big corporations, but the boundary between what is a corporation and what a nation, what an authoritarian state, and what a draconian commercial monolith has already disappeared: in order to function in any meaningful way at all, you will have to be part of the network. Try getting a mobile contract without a data package. Or booking a flight without an email address. Or buying a cup of coffee in Shanghai without a smartphone. In most cases it just isn’t possible any longer.

[WE’RE CONSTANTLY DISTRACTED, PERMANENTLY ON EDGE.]

Being a Dumb Fuck is one thing. Not being able to do anything about it though is quite something else. No wonder we are overwhelmed. We feel powerless, and not just because the man who founded Facebook uses disparaging language about us. We are fed nonstop with stimuli and sensations, and much of it is bad news: the planet is overheating, the politics is broken, and there’s another fucking pop-up. And an ad forty seconds into the video clip. Who thinks this up? If anyone behaved like that in the same room with you, you’d want to whack them over the head.

We’re stressed out because we’re constantly distracted, permanently on edge, and yet we can’t seem to let go. And we sense that these new structures we find ourselves tied into may not only be exhausting in the short term, but in fact damaging to us in the long run, too. We feel that the well-established concepts we have of what a relationship or a professional career is, or what it means to be a member of a community, are now suffering or even falling apart.

This is what makes us so nervous, so restless; and it is paradoxically also what makes every distraction appear so welcome, at least superficially: for a few seconds we can forget about the fact that we’re stressed out, even though we’ve just been disturbed. Because even if we haven’t really thought it through yet, we are aware that some major foundations of our existence are being eroded. And let’s face it: who has the time or leisure to engage with this kind of phenomenon, when it seems impossible to even put a finger on it, let alone start to deal with its magnitude?

Which is why we wrote this book. Because the question clearly isn’t, »Are you a Dumb Fuck or are you awesome?« You’re obviously both. The question is, »How can you be awesome and not get so angry that you want to hit someone, or depressed to the point where you want to throw in the towel?« Or become a dystopian miserable git obsessed with conspiracy theories who thinks that others are to blame for your woes. Or simply turn into a passive lemming who, in the absence of any obvious viable alternatives, lets everything wash over you in the hope that with a few mindfulness exercises you can at least stay sane. Once you know that this is the question, you can start to answer it, and that means you can change things.

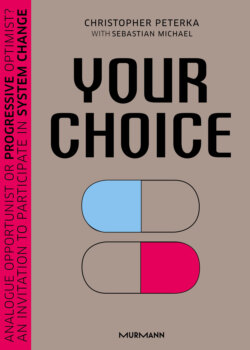

In the subtitle we call this book: »An invitation to participate in system change«. We think there is a choice to be made whether you become what we are going to call an Analogue Opportunist or a Progressive Optimist.

We also realise it’s not quite as simple as that. Or as black and white. Or, as the cover suggests, purely a question of taking the blue pill or the red one. But we also want to rattle you a bit, in the friendliest possible way. So you will find us making bold statements and drop in the odd provocation. That’s par for the course now, in the din of our world. And it, too, is a sign of our times.

The reality, as with so many other things, is that each of us is somewhere on a spectrum. Or on a grid. So we’ve included some statements at the end of each chapter which, if you answer them honestly, will yield an approximate profile of what you currently are: more of an Analogue Opportunist or more of a Progressive Optimist. And—again, as with so many other things—it’s a fluid thing this. Just because today you are really more at home in the world of yesterday, this does not mean that you need to be stuck there for all eternity. Unless, of course, to do so is your conviction, and that is what you really want: your choice. If it isn’t, then we can help you become a Progressive Optimist. In fact, we’d love it if this book were to have this effect on you.

So this big Choice that the book title offers is actually a simple one. It’s an ongoing choice that persists every day for the rest of your life: do you cave in, resign yourself, do nothing? Or do you inspire yourself, make a positive decision, change your world every day a little for the better.

We obviously have a preference. To us it makes sense: as long as you just panic, you’re paralysed and helpless. That serves the people who hold sway over you. If you’re angry, you’re emotionally charged and irrational. That serves many people who want to hold sway over you, because they find it easy to tap into this anger and make you do and say things that maybe aren’t really you. You start to see enemies where there are none, and instead of tapping into your near boundless capacity for love, you start hating things. And people. Especially ›other‹ people.

There are manipulators and agitators who want just that: for you to be angry, irrational, hateful, and violent. As long as that’s the situation, and we all fight each other, they can get away with murder. Literally.

So our contention is: yes, get angry, do panic. But once you’re through with panicking and being angry, get excited. Because you can change things. You can ›take back control‹. Of your life, of your wants and needs, of your outlook on the world, and of your relationships with your fellow humans. You can recalibrate yourself afresh. You can make the planet great again.

[YOU CAN MAKE THE PLANET GREAT AGAIN.]

It may not be possible to control all the quintillions of factors that now impact on your life. You may not have the resources to fight battles left, right, and centre. But perhaps that isn’t necessary after all. Because part of taking control of your life is letting go. Accepting that our world has become fluid, uncertain, and unpredictable. You can learn to loosen your grip freely and gracefully, and find a new kind of stability in motion. If that sounds paradoxical, that’s because it is. Be the paradox! Flourish in the liquid state of the half digital, half human existence that we’re floating towards: as much ›virtual‹ as ›real‹. You can do so anywhere in the world. Without anger. Without violence. Without hate.

And it’s true: we live in angry, violent, hateful times. Not for the first time, obviously, and unlikely for the last. But still: we need to orientate ourselves in our era and find ways of being free together without hurting each other, of hearing opinions and arguing our own without feeling offended, of creating time and space for our minds to rest and to actually think. We need to find new ways of being human. Vulnerable, beautiful, flawed; but gracious, generous, respectful too. Appreciative. Of ourselves, of the people we share this planet with, of the planet we share our life with.

And that means rebooting ourselves in the Anthropocene.

Some of you will nod sagely at this point, thinking, ›Obvs.‹ Others will be asking, ›What fresh hell is this? What, pray, is the Anthropocene?‹