Читать книгу Dylan's Visions of Sin - Christopher Ricks - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеSongs, Poems, Rhymes

Songs, Poems

Dylan has always had a way with words. He does not simply have his way with them, since a true comprehender of words is no more their master than he or she is their servant. The triangle of Dylan’s music, his voices, and his unpropitiatory words: this is still his equilateral thinking.

One day a critic may do justice not just to all three of these independent powers, but to their interdependence in Dylan’s art. The interdependence doesn’t have to be a competition, it is a culmination – the word chosen by Allen Ginsberg, who could be an awe-inspiring poet and was an endearingly awful music-maker, for whom Dylan’s songs were “the culmination of Poetry-music as dreamt of in the ’50s & early ’60s”.16 Dylan himself has answered when asked:

Why are you doing what you’re doing?

[Pause] “Because I don’t know anything else to do. I’m good at it.”

How would you describe “it”?

“I’m an artist. I try to create art.”17

What follows this clarity, or follows from it, has been differently put by him over the forty years, finding itself crediting the words and the music variously at various times. The point of juxtaposing his utterances isn’t to catch him out, it is to see him catching different emphases in all this, undulating and diverse.

WORDS RULE, OKAY?

“I consider myself a poet first and a musician second.”18

“It ain’t the melodies that’re important man, it’s the words.”19

MUSIC RULES, OKAY?

“Anyway it’s the song itself that matters, not the sound of the song. I only look at them musically. I only look at them as things to sing. It’s the music that the words are sung to that’s important. I write the songs because I need something to sing. It’s the difference between the words on paper and the song. The song disappears into the air, the paper stays.”20

NEITHER ACOUSTIC NOR ELECTRIC RULES, OKAY?

Do you prefer playing acoustic over electric?

“They’re pretty much equal to me. I try not to deface the song with electricity or non-electricity. I’d rather get something out of the song verbally and phonetically than depend on tonality of instruments.”21

JOINT RULE, OKAY?

Would you say that the words are more important than the music?

“The words are just as important as the music. There would be no music without the words.”22

“It’s not just pretty words to a tune or putting tunes to words, there’s nothing that’s exploited. The words and the music, I can hear the sound of what I want to say.”23

“The lyrics to the songs . . . just so happens that it might be a little stranger than in most songs. I find it easy to write songs. I have been writing songs for a long time and the words to the songs aren’t written out for just the paper, they’re written as you can read it, you dig? If you take whatever there is to the song away – the beat, the melody – I could still recite it. I see nothing wrong with songs you can’t do that with either – songs that, if you took the beat and melody away, they wouldn’t stand up. Because they’re not supposed to do that you know. Songs are songs.”24

What’s more important to you: the way that your music and words sound, or the content, the message?

“The whole thing while it’s happening. The whole total sound of the words, what’s really going down is –”25

– at which point Dylan cuts across himself, at a loss for words with which to speak of words in relation to the whole total: “it either happens or it doesn’t happen, you know”. At a loss, but finding the relation again and again in the very songs.

It ought to be possible, then, to attend to Dylan’s words without forgetting that they are one element only, one medium, of his art. Songs are different from poems, and not only in that a song combines three media: words, music, voice. When Dylan offered as the jacket-notes for Another Side of Bob Dylan what mounted to a dozen pages of poems, he headed this Some Other Kinds of Songs . . . His ellipsis was to give you time to think. In our time, a dot dot dot communication.

Philip Larkin was to record his poems, so the publishers sent round an order form inviting you to hear the voice of the Toads bard. The form had a message from the poet, encouraging you – or was it discouraging you? For there on the form was Larkin insisting, with that ripe lugubrious relish of his, that the “proper place for my poems is the printed page”, and warning you how much you would lose if you listened to the poems read aloud: “Think of all the mis-hearings, the their / there confusions, the submergence of rhyme, the disappearance of stanza shape, even the comfort of knowing how far you are from the end.” Again, Larkin in an interview, lengthening the same lines:

I don’t give readings, no, although I have recorded three of my collections, just to show how I should read them. Hearing a poem, as opposed to reading it on the page, means you miss so much – the shape, the punctuation, the italics, even knowing how far you are from the end. Reading it on the page means you can go your own pace, take it in properly; hearing it means you’re dragged along at the speaker’s own rate, missing things, not taking it in, confusing “there” and “their” and things like that. And the speaker may interpose his own personality between you and the poem, for better or worse. For that matter, so may the audience. I don’t like hearing things in public, even music. In fact, I think poetry readings grew up on a false analogy with music: the text is the “score” that doesn’t “come to life” until it’s “performed”. It’s false because people can read words, whereas they can’t read music. When you write a poem, you put everything into it that is needed: the reader should “hear” it just as clearly as if you were in the room saying it to him. And of course this fashion for poetry readings has led to a kind of poetry that you can understand first go: easy rhythms, easy emotions, easy syntax. I don’t think it stands up on the page.26

The human senses have different powers and limits, which is why it is good that we have five (or is it six?) of them. When you read a poem, when you see it on the page, you register – whether consciously or not – that this is a poem in, say, three stanzas: I’ve read one, I’m now reading the second, there’s one to go. This is the feeling as you read a poem, and it’s always a disconcerting collapse when (if your curiosity hasn’t made you flick over the pages before starting the poem) you turn the page and find, “Oh, that was the end. How curious.” Larkin’s own endings are consummate. And what he knows is that your ear cannot hear the end approaching in the way in which your eye – the organ that allows you to read – sees the end of the poem approaching. You may, of course, know the music well, and so be well aware that the end is coming, but such awareness is a matter of familiarity and knowledge, whereas with a poem that you have never seen before, you yet can see perfectly well that this is the final stanza that you are now reading.

Of sonnet-writing, Gerard M. Hopkins wrote of both seeing and hearing “the emphasis which has been gathering through the sonnet and then delivers itself in those two lines seen by the eye to be final or read by the voice with a deepening of note and slowness of delivery”.27

For the eye can always simply see more than it is reading, looking at; the ear cannot, in this sense (given what the sense of hearing is), hear a larger span than it is receiving. This makes the relation of an artist like Dylan to song and ending crucially different from the relation of an artist like Donne or Larkin to ending. The eye sees that it is approaching its ending, as Jane Austen can make jokes about your knowing that you’re hastening towards perfect felicity because there are only a few pages left of the novel. A novel physically tells you that it is about to come to an end. The French Lieutenant’s Woman in one sense didn’t work, couldn’t work, because you knew perfectly well that since it was by John Fowles and not by a post-modernist wag there was bound to be print on those pages still to come, the last hundred pages. So it couldn’t be about to end, isn’t that right?, because this chunk of it was still there, to come. But then John Fowles, like J. H. Froude, whose Victorian novel he was imitating in this matter of alternative endings, knows this and tries to build this, too, into the effect of his book.

Dylan has an ear for a tune, whether it’s his, newly minted, or someone else’s, newly mounted. He has a voice that can’t be ignored and that ignores nothing, although it spurns a lot. Dylan when young did what only great artists do: define anew the art he practised. Marlon Brando made people understand something different by acting. He couldn’t act? Very well, but he did something very well, and what else are you going to call it? Dylan can’t sing?

Every song, by definition, is realized only in performance. True. A more elusive matter is whether every song is suited to re-performance. Could there be such a thing as a performance that you couldn’t imagine being improved upon, even by a genius in performance? I can’t imagine his doing better by The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll, for instance, than he does on The Times They Are A-Changin’. Of course I have to concede at once that my imagination is immensely smaller than his, and it would serve me right, as well as being wonderfully right, if he were to prove me wrong. But, as yet, what (for me) is gained in a particular re-performing of this particular song (and yes, there are indeed gains) has always fallen short of what had to be sacrificed. Any performance, like any translation, necessitates sacrifice, and I believe that it would be misguided, and even unwarrantably protective of Dylan, to suppose that his decisions as to what to sacrifice in performance could never be misguided. Does it not make sense, then, to believe, or to argue, that Dylan’s realizing of The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll was perfect, a perfect song perfectly rendered, once and for all?

Clearly Dylan doesn’t believe so, or he wouldn’t re-perform it. He makes judgements as to what to perform again, and he assuredly does not re-perform every great song (you don’t hear Oxford Town or Sad-Eyed Lady of the Lowlands in concert). Admittedly there are a good many good reasons why a song might not be re-performed, matters of quality newly judged, or aptness to an occasion or to a time, or a change of conviction, all of which means that the entire rightness of a previous performance wouldn’t have to be what was at issue. Still, Dylan takes bold imaginative decisions as to what songs to re-perform, so can we really not ask whether there are occasions on which a particular decision, though entirely within his rights and doing credit to his renovations and aspirations and audacities, is one for which the song has been asked to pay too high a price? “Those songs have a life of their own.”28

I waver about this when it comes to this song, one of Dylan’s greatest, The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll, even while I maintain that the historical songs, the songs of conscience, can’t be re-created in the same way as the more personal (not more personally felt) songs of consciousness, with the same kind of freedom. “The chimes of freedom” sometimes have to be in tune with different responsibilities. Dylan can’t, I believe, command a new vantage-point (as he might in looking back upon a failed love or a successful one) from which to see the senseless killing of Hattie Carroll. Or, at least, the question can legitimately come up as to whether he can command a new vantage-point without commanding her and even perhaps wronging her.

He makes the song new, yes, but in the mid 1970s, for example, he sometimes did so by sounding too close for comfort to the tone of William Zanzinger’s tongue (“and sneering, and his tongue it was snarling”). “Doomed and determined to destroy all the gentle”: the song is rightly siding with the gentle, and it asks (asks this of its creator, too) that it be sounded gently. But then the song can be sung too gently, with not enough sharp-edged dismay.

I used to put this too categorically, and therefore wrongly:

He cannot re-perform the song. He unfortunately still does. There is no other way of singing this song than the way in which he realizes it on The Times They Are A-Changin’. If he sings it any more gently, he sentimentalizes it. If he sings it any more ungently, he allies himself with Zanzinger.29

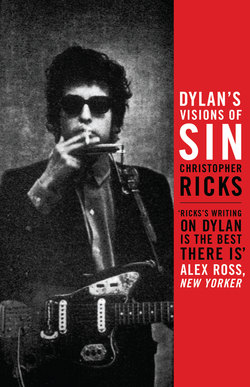

Alex Ross, of the New Yorker, who is generous towards my appreciation of Dylan, thinks any such reservation narrow-minded of me:

Ricks went on to criticize some of Dylan’s more recent performances of Hattie Carroll, in which he pushes the last line a little: “He doesn’t let it speak for itself. He sentimentalizes it, I’m afraid.” Here I began to wonder whether the close reader had zoomed in too close. Ricks seemed to be fetishizing the details of a recording, and denying the musician license to expand his songs in performance.30

I bridle slightly at that fetishizing-a-recording bit. (What, me? All the world knows that it is women’s shoes that I am into.) Nor do I think of myself as at all denying Dylan licence to expand his songs. (Who’s going to take away his licence to expand?) I’m only proposing that, although he has entire licence in any such matter, freedom is different from (in one sense) licence, and it must be that on occasion an artist who is on a scale to take immense risks will fall short of his newest highest hopes. Samuel Beckett has the courage to fail, and he urges fail better. He knows there’s no success like failure. And that it is not clear what success would mean if failure were not exactly rare but simply unknown. Dylan in 1965:

I know some of the things I do wrong. I do a couple of things wrong. Once in a while I do something really wrong, y’ know, which I really can’t see when I’m involved in it; and after a while I look at it later, I know it’s wrong. I don’t say nothin’ about it.31

It is the greatest artists who have taken the greatest risks, and it is impossible to see what it would mean to respect the artists for this if on every single occasion you were to find that the risks that were run simply ran away. Doesn’t it then start to look as though the risks were only “risks”? If you were, for instance, to think of revision as a form that re-performing may take when it comes to the written word, it is William Wordsworth and Henry James, the most imaginative and unremitting of revisers, who on occasion get it wrong and who lose more than they gain when it comes to some of their audacious post-publication revisions.

Hattie Carroll is a special, though not a unique, case. “License to expand his songs”? But strait is the gate, and narrow is the way, which leadeth unto life, and few there be that find it. It must at least be possible that the gains of re-performing this particular song could fall short of the losses.

Alex Ross went on at once to evoke beautifully the beauty of a particular re-performing:

I had just seen Dylan sing Hattie Carroll, in Portland, and it was the best performance that I heard him give. He turned the accompaniment into a steady, sad acoustic waltz, and he played a lullabylike solo at the center. You were reminded that the “hotel society gathering” was a Spinsters’ Ball, whose dance went on before, during, and after the fatal attack on Hattie Carroll. This was an eerie twist on the meaning of the song, and not a sentimental one.

Why am I, though touched by this, not persuaded by it? Because when Ross says “You were reminded that the ‘hotel society gathering’ was a Spinsters’ Ball”, his word “reminded” is specious. At no point in Hattie Carroll is there any allusion to this. You can have heard the song a thousand times and not call this to mind, since Dylan does not call it into play. Is Ross really maintaining that the performance alluded to a detail of the newspaper story that never made it into the song, which doesn’t say anything about a Ball, Spinsters’ or Bachelors’? And that such an allusion would then simply validate a thoroughgoing waltz?

Dylan must be honoured for honouring his responsibilities towards Hattie Carroll, and this partly because of what it may entail in the way of sacrifice by him. His art, in such a dedication to historical facts that are not of his making, needs to set limits (not too expanded) to its own rights in honouring hers. This, too, is a matter of justice.

Wordsworth famously recorded that “every author, as far as he is great and at the same time original, has had the task of creating the taste by which he is to be enjoyed: so it has been, so will it continue to be”.32 T. S. Eliot, sceptical of romanticism, offered a reminder, that “to be original with the minimum of alteration, is sometimes more distinguished than to be original with the maximum of alteration”.33

But is Dylan a poet? For him, no problem.

Yippee! I’m a poet, and I know it

Hope I don’t blow it

(I Shall Be Free No. 10)

Is he a poet? And is this a question about his achievement, and how highly to value it, or about his choice of medium or rather media, and what to value this as?

The poetry magazine Agenda had a questionnaire bent upon rhyme. Since Dylan is one of the great rhymesters of all time, I hoped that there might be something about him. There was: a grudge against “the accepted badness of rhyme in popular verse, popular music, etc. A climate in which, say, Bob Dylan is given a moment’s respect as a poet is a climate in which anything goes.” (To give him but a moment’s respect would indeed be ill judged.) This is snobbery – I know, I know, there is such a thing as inverted snobbery – and it’s ill written.34 (“A climate in which anything goes”? Climate? Goes?)

The case for denying Dylan the title of poet could not summarily, if at all, be made good by any open-minded close attention to the words and his ways with them. The case would need to begin with his medium, or rather with the mixed-media nature of song, as of drama. On the page, a poem controls its timing there and then.

Dylan is a performer of genius. So he is necessarily in the business (and the game) of playing his timing against his rhyming. The cadences, the voicing, the rhythmical draping and shaping don’t (needless to sing) make a song superior to a poem, but they do change the hiding-places of its power. T. S. Eliot showed great savvy in maintaining that “Verse, whatever else it may or may not be, is itself a system of punctuation; the usual marks of punctuation themselves are differently employed.”35 A song is a different system of punctuation again. Dylan himself used the word “punctuate” in a quiet insistence during an interview in 1978. Ron Rosenbaum made his pitch – “It’s the sound that you want” – and Dylan agreed and then didn’t: “Yeah, it’s the sound and the words. Words don’t interfere with it. They – they – punctuate it. You know, they give it purpose. [Pause].”

“They – they – punctuate it”: this is itself dramatic punctuation, though perfectly colloquial (and Dylan went on to say “Chekhov is my favorite writer”).36 Words: “they give it purpose. [Pause]”, the train of thought being that punctuation, a system of pointing, gives point.

Not just the beauty but the force will be necessarily in the details, incarnate in a way of putting it. So that any general praises of Dylan’s art are sure to miss what matters most about it: that it is not general, but highly and deeply individual, particular. This, while valuing human commonalty – “Of joy in widest commonalty spread”, in Wordsworth’s line. Joy, and grief, too.

Larkin, reviewing jazz in 1965, took it on himself to nick a Dylan album. (Hope I’m not out of line.)

I’m afraid I poached Bob Dylan’s “Highway 61 Revisited” (CBS) out of curiosity and found myself well rewarded. Dylan’s cawing, derisive voice is probably well suited to his material – I say probably because much of it was unintelligible to me – and his guitar adapts itself to rock (“Highway 61”) and ballad (“Queen Jane”) admirably. There is a marathon “Desolation Row” which has an enchanting tune and mysterious, possibly half-baked words.37

“Half-baked” is overdone. But “well rewarded” pays some dues.

A poem of Larkin’s has the phrase “Love Songs” in its title and is about songs, while itself proceeding not as a song but as a poem. For when you see the poem on the page, you can see that it is in three stanzas, and you could not at once hear – though you might know – such a thing when in the presence of a song. Larkin, we have already heard, thought that “poetry readings grew up on a false analogy with music”: “false because people can read words, whereas they can’t read music”. But this poem of his contemplates someone who used to be able to read music and play it on the piano, and who can still, in age, look at the sheet music and re-learn how it is done.

LOVE SONGS IN AGE

She kept her songs, they took so little space,

The covers pleased her:

One bleached from lying in a sunny place,

One marked in circles by a vase of water,

One mended, when a tidy fit had seized her,

And coloured, by her daughter –

So they had waited, till in widowhood

She found them, looking for something else, and stood

Relearning how each frank submissive chord

Had ushered in

Word after sprawling hyphenated word,

And the unfailing sense of being young

Spread out like a spring-woken tree, wherein

That hidden freshness sung,

That certainty of time laid up in store

As when she played them first. But, even more,

The glare of that much-mentioned brilliance, love,

Broke out, to show

Its bright incipience sailing above,

Still promising to solve, and satisfy,

And set unchangeably in order. So

To pile them back, to cry,

Was hard, without lamely admitting how

It had not done so then, and could not now.

A widow comes across the love songs that she had played on the piano when she was young; how painfully they remind her of the large promises once made by time and even more by love. 38

That sentence exercises a summary injustice. It is not much more than perfunctory gossip, whereas Larkin’s three sentences are a poem. The poet makes these dry bones live – or rather, since he is not a witch-doctor and the poem is not a zombie, he makes us care that these bones lived. “An ordinary sorrow of man’s life”: that is how Wordsworth spoke of his lonely sufferer (in widowhood, likewise?) in her ruined cottage. Larkin, too, redeems the ordinary.

His is not a poem simply about life’s disappointments, but about realizing these disappointments. He reminds us that to realize is to make real. Here are three sentences that shrink as life cannot but shrink. From 106 words to 30 to 23. The first sentence has all the amplitude of the remembered past into which it moves. It has world enough and time, with lovingly remembered details calmly patterned (“One bleached . . . One marked . . . One mended”), a world “set in order”. It flows on, and its own words remark on what they are re-living – they “spread out”, they manifest a sense of “time laid up in store”. The first sentence can take its time – time is not doing the taking.

But from this leisure the second sentence dwindles. It begins with “But”, unlikely to be a reassuring start here, and instead of what is lovingly recalled, we have love itself. Instead of the actually loved, in its inevitable imperfection (the unmentioned husband, the mentioned daughter), there is the daunting abstraction, love. Its brilliance is a “glare”, too bright to be ignored, somehow pitiless in its “sailing above”. And if love “broke out” in those songs, here, too, there is something of an ominous suggestion. Light breaks out, but so do wars and plagues. Love, too, can break hearts, or cannot but break hearts if we think of all that the abstraction love promised.

Then the further shrinkage into the last sentence, briefer, bleaker. Instead of the abstraction of the middle sentence, which was large and metaphorical and aerial, we reach a stony abstraction – no metaphors, no details, no grand words like “incipience”. Simply pain generalized, compacted into the plainest words in the language. Earlier the poem had opened its mouth and sung; in the end it bites its lip.

From copious memories recalling what promised to be a copious future, through high hopes, down to severe humbling. From a romantic compound, “spring-woken”, through a laconically dry one, “much-mentioned”, down to uncompounded plainness. From “a tidy fit”, through the promise to “set unchangeably in order”, down to “pile them back”.

Yet this is poetry, not prose, so it exists not only as sentences but as lines and stanzas. Larkin is a master of all such patterning. The pattern does not impose itself upon the sense, it releases and enforces the sense. See how he uses line-endings and stanza-endings – “see how”, because this is much more possible than “hear how”. Larkin’s point about “the disappearance of stanza shape” when you hear a poem read aloud can be extended to include our being able to see the valuable counterpointing of stanza shape and, say, sentence shape. A song’s stanzas are less concerned to stand, more to move.

Love Songs in Age has no stanza that is self-contained. There is a marked visual pause in passing from the first to the second stanza:

So they had waited, till in widowhood

She found them, looking for something else, and stood

Relearning how each frank submissive chord

Had ushered in

Word after sprawling hyphenated word,

(“Sprawling hyphenated”, because the sheet-music sets the words, subdivided and stretched out, below the musical notes, so Larkin can remind us of the different systems of punctuation that are poetical and sheet-musical.) The visual pause after “stood” is all the more effective because in the first six lines of the poem the lines have been placidly end-stopped, tidily congruous, the units of sense at one with (rather than played against) the units of rhythm and rhyme.

Then, with “stood”, a powerful pause enforces itself – the poem pauses, rapt, just as the widow pauses here, rapt into memory. Swelling in the second stanza is a change from the equable line-endings of the first. Instead of such a complete unit as “The covers pleased her”, there is the line “Had ushered in”, which has to move on from its predecessor and to usher in its successor. The ebullience of this middle stanza spreads out over its line-endings, the clauses proliferate and spill over (“. . . in / . . . wherein”). And then, at the very end of the stanza, a sudden drastic check:

That certainty of time laid up in store

As when she played them first. But, even more,

The glare of that much-mentioned brilliance, love,

With a harsh gracelessness, the second sentence is imperatively beginning, tugging across the cadences (and, duly, demanding a pause). If the opening of this second sentence, “But”, is threateningly ungraceful, how much more is the third: “So” thrust out with grim emphasis, cutting across the order that immediately precedes it, insisting doggedly on the truth:

Still promising to solve, and satisfy,

And set unchangeably in order. So

To pile them back, to cry,

Was hard, without lamely admitting how

It had not done so then, and could not now.

The point of running one stanza into the next is more than to create pregnant pauses, more even than to imitate the musical interweaving of love songs. It is to create the austere finality of the conclusion. Only once in this poem does a full stop coincide with the end of a line or with the end of a stanza. This establishes the fullness of this stop, the assurance that Larkin has concluded his poem and not just run out of things to say. The same authoritative finality is alive in the rhyme scheme. Larkin’s pattern (abacbdcdd) allows of a clinching couplet only at the end of a stanza. He then prevents any such clinching at the end of the first two stanzas by having very strong enjambment, spilling across the line-endings. The result is that the very last couplet is the first in the poem to release what we have been waiting for, the decisive authority of a couplet, rhyme sealing rhyme in a final settlement. But also with a rhythmical catch in the throat, a brief stumble before “lamely”: “Was hard, without lamely admitting how” is aline that cannot move briskly, has to feel lamed, because of the speed-bump between “without” and “lamely”. And then an inexorable ending, here and now: “and could not now”. The poem focuses time, much as time focuses itself for us in the dentist’s chair into a concentrated “now”.

The conclusive couplet isn’t the only subtly meaningful rhyming. The gentle disyllabic, or double, rhymes of the first stanza (pleased her / seized her, water / daughter) create softer cadences, all the more so because of the -er association among themselves. It is against this softer light that the glare of the last stanza stands out, its rhymes bleak. Only one rhyme in the poem is inexact, and with good reason: chord / word. That the words of life do not quite fit its music is one of the things that the poem knows.

Love Songs in Age is far more than a five-finger exercise in the manner of the poet whom Larkin most admired, Thomas Hardy. Like the best of Hardy, the best of Larkin lives in the context of an imagined life. The widow’s story is there, between the poem’s lines, treated obliquely and unsentimentally. The appeal is to experiences already understood (“That hidden freshness”, “That certainty”, “That much-mentioned brilliance”). “She kept her songs, they took so little space” – how much of an everyday sadness is here, of possessions sold off, a home relinquished, the life lived in what Larkin elsewhere calls (in Mr Bleaney) a “hired box”. The songs, she kept – the piano, she could not (though this, too, has to be glimpsed between the lines, especially in “stood / / Relearning . . .”). Self-possession is bound to be so much involved with possessions.

Yet the end of the poem makes a point rather different from the expected. It doesn’t say that she cried or wanted to cry, but that it was hard to cry without admitting how huge the failure of love had been in comparison with any triumphs of love. Not hard to cry, heaven knows, but hard to cry without dissolving, hard to admit any cause for grief without admitting too shatteringly much. “Admitting”: in its unostentatious truth-telling, it is a perfect Larkin word. Not that memory is merely unkind. When we look back across the whole poem, we realize that it was not only in the literal physical sense that “She kept her songs”. Meantime, the poem at least has set something unchangeably in order.

Such, at any rate, is my reading of the poem. To hear the poem read aloud, even by the poet himself, is a different story. Yet the story turns upon the same sad pertinent fact: that the only rhyme that is not a true rhyme, the only one that is a rhyme only to the eye and not to the ear, is chord / word. For ever refusing to fit, to be set perfectly in order. There on the page, like sheet-music that both is and is not the real thing.

Dylan said of Lay, Lady, Lay: “The song came out of those first four chords. I filled it up with the lyrics then.” And elsewhere he said something that suggests the economy that characterizes such a poem as Love Songs in Age: “Every time I write a song, it’s like writing a novel. Just takes me a lot less time, and I can get it down . . . down to where I can re-read it in my head a lot.”39

Love Songs in Age is a poem that imagines songs within it, and shows us what this might mean, humanly. I don’t know of a counterpart to this in Dylan: that is, a song that imagines poems within it, as against bearing them in mind. Poets like Verlaine and Rimbaud, Dylan is happy to acknowledge. But when it comes to Dylan and the sister-arts, it is, naturally, the traditional sister-art of butter sculpture that most engages his interest, as does the traditional relation between the artist and his brother, the critic.

look you asshole – tho i might be nothing but

a butter sculptor, i refuse to go on working

with the idea of your praising as my reward –

like what are your credentials anyway? excpt for

talking about all us butter sculptors, what else

do you do? do you know what it feels like to

make some butter sculpture? do you know what

it feels like to actually ooze that butter around

& create something of fantastic worth? you said

that my last year’s work “The King’s Odor” was

great & then you say i havent done anything as

great since – just who the hell are you talking to

anyway? you must have something to do in your

real life – i understand that you praised the piece

you saw yesterday entitled “The Monkey Taster”

about which you said meant “a nice work of butter

carved into the shape of a young man who likes

only african women” you are an idiot – it doesnt

mean that at all . . . i hereby want nothing to do

with your hangups – i really dont care what you think

of my work as i now know you dont understand it

anyway . . . i must go now – i hve this new hunk of

margarine waiting in the bathtub – yes i said

MARGARINE & next week i just might decide to use

cream cheese –40

But, butter sculpture apart, it is famously the art of film that Dylan most likes to stage or to screen within his songs. And the greatest of such is Brownsville Girl.41 It starts Well.

Well, there was this movie I seen one time

About a man riding ’cross the desert and it starred Gregory Peck

He was shot down by a hungry kid trying to make a name for himself

The townspeople wanted to crush that kid down and string him up by the neck

I once tried to sum up why it earned its place among his Greatest Hits, third time around:

The end of an age, an age ago, ending “long before the stars were torn down”. At 11 minutes, it has world enough and time to be a love story, a trek, a brief epic . . . Patience, it urges. We wait for eager ages for his voice to introduce us to the Brownsville Girl herself. Great rolling stanzas (“and it just comes a-rolling in”), and memories of the Rolling Thunder Revue, especially since Sam Shepard plays his part. About films, it has the filmic flair of Dylan’s underrated masterpiece, Renaldo and Clara. Delicious yelps from the back-up women, who sometimes comically refuse to back him up. He: “They can talk about me plenty when I’m gone.” They: “Oh yeah?” It moves, and yet stays put, circling back round. One of those great still songs.42

What particularly takes Dylan about films, I take it, is that they move – why else would they be movies? – while at the same time or in a different sense they don’t. Don’t thereafter move from what they once were. For to film it is to fix it. And a re-make of a film is not the same thing as re-performing a song. Like Brownsville Girl, a film – including this one within the song that someone remembers or kinda remembers – moves and yet stays still. It stays more than just stills, that is true, but to see it again is to see it exactly as it was, for all time. (Eternity is a different story.) There is comedy in Brownsville Girl’s beginning “Well, there was this movie I seen one time”, for although “one time” makes perfectly good sense and we know what he means, it is going to be many more than one time that we shall hear tell of his seeing it. The second time it goes, or rather, arrives, like this:

Something about that movie though, well I just can’t get it out of my head

But I can’t remember why I was in it or what part I was supposed to play

All I remember about it was Gregory Peck and the way people moved

And a lot of them seemed to be lookin’ my way

The way people moved, and meanwhile the film moved, and how they looked out my way from the screen as though I were the performer (no longer “a hungry kid trying to make a name for himself ”), not – on this relief of an occasion – the performee. And yet the film, once and for all, is not going to move, or move out of my head. Even when an actor returns in the re-make of a film, as did Robert Mitchum for the second Cape Fear, he is not himself or is not his previous self. One man in his time plays many parts. And so the song muses on the Muse of Film:

Well, I’m standing in line in the rain to see a movie starring Gregory Peck

Yeah, but you know it’s not the one that I had in mind

He’s got a new one out now, I don’t even know what it’s about

But I’ll see him in anything so I’ll stand in line

A new one out now, the old one being in then, preserving its people, just as they were, for ever and a day. “Welcome to the land of the living dead.” Not just The Night of the Living Dead, which is one particular film, but the land of the living dead, filmland. “I’ll stand in line”: much is made of lines in this song, the medium of song being lines and it’s not being only Dylan’s audience that has to be willing to stand in line. Any song must. And Dylan reels out the lines themselves, one of the furthest extended being a line that does indeed find itself over the line (we forgive it its trespasses):

Now I’ve always been the kind of person that doesn’t like to trespass but sometimes you just find yourself over the line

And then, as the song winds to a conclusion, it winds back to the beginning, this time underlining “one time” with “twice”:

There was a movie I seen one time, I think I sat through it twice

I don’t remember who I was or where I was bound

All I remember about it was it starred Gregory Peck, he wore a gun and he was shot in the back

Seems like a long time ago, long before the stars were torn down

And so – in this requiem for the stars, the living dead – on to the refrain for the last time, a refrain that is a showing, or a plea for a showing:

Brownsville girl with your Brownsville curls

Teeth like pearls shining like the moon above

Brownsville girl, show me all around the world

Brownsville girl, you’re my honey love

Show me all around the world: that is all that any film asks.

There is in Dylan’s songs a sense that competition between sister-arts is as inevitable and (mostly) as unproductive as any other sibling rivalry, but that only a very touchy visual artist would object to a singer’s envisaging the day When I Paint My Masterpiece. But there is (praise be) such a thing as stealthy competition.

Praise be to Nero’s Neptune

The Titanic sails at dawn

And everybody’s shouting

“Which Side Are You On?”

And Ezra Pound and T. S. Eliot

Fighting in the captain’s tower

While calypso singers laugh at them

And fishermen hold flowers

Between the windows of the sea

Where lovely mermaids flow

And nobody has to think too much

About Desolation Row

There is some pitching of poems against songs here. The question “Which Side Are You On?” can be approached from many sides, one being the premiss that these words will strike slightly differently upon the ear. For it is the case that not even Dylan can unmistakably sing the difference between upper and lower case (not “Which side are you on?”), whereas to the eye the distinction is a Piece of Cake. It’s just that there is something that you need to know. The capital title of that unmisgiving political song.

So the central contention turns out not to be between those two heavyweight modernists, or between their high art and that of the lowly calypso, or between poems and songs, or even between the Titanic and the iceberg,43 but between two deeply different apprehensions of what it is that songs can most responsibly be. And of what the world truly is, as against the simplicities of Once upon a time. “An I see two sides man” –

It was that easy –

“Which Side’re You On” aint phony words

An’ they aint from a phony song44

Dylan didn’t like to bad-mouth a song that was in a good cause. But he knew, even back then in 1963, that this “two sides” business was averting its eyes and its ears from too much. So before long he was hardening his art. “Songs like ‘Which Side Are You On?’ . . . they’re not folk-music songs; they’re political songs. They’re already dead.”45

What does the word protest mean to you?

“To me? Means uh . . . singing when I don’t really wanna sing.”

What?

“It means singing against your wishes to sing.”

Do you sing against your wishes to sing?

“No, no.”

Do you sing protest songs?

“No.”

What do you sing?

“I sing love songs.”46

Love songs in age, as in youth.

Rhymes

“What is rhyme?” said the Professor. “Is it not an agreement of sound –?” “With a slight disagreement, yes” broke in Hanbury. “I give up rhyme too.” “Let me however” said the Professor “in the moment of triumph insist on rhyme, which is a short and valuable instance of my principle. Rhyme is useful not only as shewing the proportion of disagreement joined with agreement which the ear finds most pleasurable, but also as marking the points in a work of art (each stanza being considered as a work of art) where the principle of beauty is to be strongly marked, the intervals at which a combination of regularity with disagreement so very pronounced as rhyme may be well asserted, the proportions which may be well borne by the more markedly, to the less markedly, structural. Do you understand?”

“Yes” said Middleton. “In fact it seems to me rhyme is the epitome of your principle. All beauty may by a metaphor be called rhyme, may it not?”

Gerard M. Hopkins (On the Origin of Beauty: A Platonic Dialogue)47

Rhyme, in the words of The Oxford English Dictionary, is “Agreement in the terminal sounds of two or more words or metrical lines, such that (in English prosody) the last stressed vowel and any sounds following it are the same, while the sound or sounds preceding are different. Examples: which, rich; grew, too . . .”

A device, a matter of technique, then, but always seeking a relation of rhyme to reason (without reason or rhyme?), so that “technique” ought to come to seem too small a word and we will find ourselves thinking rather of a resource. Rhymes and rhythms and cadences will be what brings a poem home to us.

People have always complained that rhyme puts pressure on poets to say something other than what they really mean to say, and people have objected to Bob Dylan’s rhyming. Ellen Willis told him off: “He relies too much on rhyme.”48 It’s like some awful school report: you’re allowed to rely on rhyme 78 per cent, but Master Dylan relies on rhyme 81 per cent. Anyway, you can’t rely too much on rhyme, though you can mistake unreliable rhymes for reliable ones.

For success, there is the simple (not easy) stroke that has the line, “Oh, Mama, can this really be the end?”, not as the end, but as nearing the end of each verse of Stuck Inside of Mobile with the Memphis Blues Again. And the rhyme in this refrain is beautifully metaphorical, because it’s a rhyme of the word “end” with the word “again”:

Oh, Mama, can this really be the end

To be stuck inside of Mobile

With the Memphis Blues again?

“End” and “again” are metaphorically a rhyme because every rhyme is both an endness and an againness. That’s what a rhyme is, intrinsically, a form of again (a gain, too), and a form of an ending.

In Death is Not the End, each verse ends:

Just remember that death is not the end

Not the end, not the end

Just remember that death is not the end

And the four verses at first maintain the tolling of this severe rhyme: friend / mend, comprehend / bend, descend / lend, and then at last soften it, though not much, from an end rhyme into the assonance men / citizen. (Assonance differs from rhyme in not having the same end.) But just remember that the song has not only four verses but a bridge, and that the bridge (a bridge to the next world) is variously at a great remove from the sound of that particular rhyming or assonance on end, having instead the sound-sequence that springs from life: dies / bright light / shines / skies:

Oh, the tree of life is growing

Where the spirit never dies

And the bright light of salvation shines

In dark and empty skies

The rhyme dies / skies depends upon its distance from the end sound, just as it depends upon “dies” being, in full, “never dies”. The bridge is, then, at a great remove. And yet it is not complacently or utterly removed from the end-world, given the sound in “empty”.

“All beauty may by a metaphor be called rhyme, may it not?” asked a speaker in Hopkins’s imaginary conversation. Moreover, rhyme is itself one of the forms that metaphor may take, since rhyme is a perception of agreement and disagreement, of similitude and dissimilitude. Simultaneously, a spark. Long, long ago, Aristotle said in the Poetics that the greatest thing by far is to be a master of metaphor, for it is upon our being able to learn from the perception of similitude and dissimilitude that human learning of all kinds depends. One form that mastery of metaphor may take is mastery of rhyme.

Ian Hamilton said of “Dylan’s blatant, unworried way with rhyme” in All I Really Want to Do that it is irritating on the page, but sung by him it very often becomes part of the song’s point, part of its drama of aggression. Many of Dylan’s love songs are a kind of verbal wife-battering: she will be rhymed into submission – but to see them this way you have to have Bob’s barbed wire tonsils in support.49

I think it’s true that women in Dylan’s vicinity sometimes have as their mission being rhymed into submission, but that isn’t battering, it’s bantering.

Still, the rhyming can be fierce. Take the force of the couplet in Idiot Wind,

Blowing like a circle round my skull

From the Grand Coulee Dam to the Capitol

Rolling Stone reported: “It’s an amazing rhyme, Ginsberg writes, an amazing image, a national image like in Hart Crane’s unfinished epic of America, The Bridge. The other poet is delighted to get the letter. No one else, Dylan writes Ginsberg, had noticed that rhyme, a rhyme which is very dear to Dylan. Ginsberg’s tribute to that rhyme is one of the reasons he is here”:50 that is, on the Rolling Thunder Review and then in Dylan’s vast film Renaldo and Clara.

And it’s a true rhyme because of the metaphorical relation, because of what a head of state is, and the body politic, and because of the relation of the Capitol to the skull (another of those white domes), with which it disconcertingly rhymes. An imperfect rhyme, perfectly judged.

Dylan: “But then again, people have taken rhyming now, it doesn’t have to be exact anymore. Nobody’s gonna care if you rhyme ‘represent’ with ‘ferment’, you know. Nobody’s gonna care.”51 Not going to care as not going to object, agreed; but someone as imaginative about rhymes as Dylan must care, since always aware of, and doing something with, imperfect rhymes, or awry rhymes, or rhymes that go off at half-cock, so that their nature is to the point. The same goes for having assonance instead of rhyme: entirely acceptable but not identical with the effect of rhyme, and creatively available as just that bit different. The rhyme skull / Capitol is a capital one.

Dylan adapts the skull of the Capitol to the White House elsewhere, in 11 Outlined Epitaphs:

how many votes will it take

for a new set of teeth

in the congress mouths?

how many hands have t’ be raised

before hair will grow back

on the white house head?

But can it be that Dylan was guilty of baldism? A bad hair day. Time to soothe and smoothe: A Message from Bob Dylan to the Emergency Civil Liberties Committee (13 December 1963) assured those of us who are bald oldsters or baldsters that “when I speak of bald heads, I mean bald minds”. You meant bald heads, and it was a justified generational counter-attack, given how the young (back then) were rebuked for their hair.

A rhyme may be a transplant.

The highway is for gamblers, better use your sense

Take what you have gathered from coincidence

(It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue)

One of the best rhymes, that. For all rhymes are a coincidence issuing in a new sense. It is a pure coincidence that sense rhymes with coincidence, and from this you gather something. Every rhyme issues a bet, and is a risk, something for gamblers – and a gambler is a better (“for gamblers, better use . . .”).

Granted, it is possible that all this is a mere coincidence, and that I am imagining things, rather than noticing how Dylan imagined things. We often have a simple test as to whether critical suggestions are far-fetched. If they hadn’t occurred to us, they are probably strained, silly-clever . . . So although for my part I believe that the immediate succession “gamblers, better . . .” is Dylan’s crisp playing with words, not my doing so, and although I like the idea that there may be some faint play in the word “sense”, which in the American voicing is indistinguishable from the small-scale financial sense “cents”,52 I didn’t find myself persuaded when a friend suggested that all this money rolls and flows into “coincidence”, which does after all start with c o i n, coin. Not persuaded partly, I admit, because I hadn’t thought of it myself, but mostly because this is a song, not a poem on the page. On the page, you might see before your very eyes that coincidence spins a coin, but the sound of a song, the voicing of the word “coincidence”, can’t gather coin up into itself. Anyway Dylan uses his sense. “One of the very nice things about working with Bob is that he loves rhyme, he loves to play with it, and he loves the complication of it.”53 A quick canter round the course of his rhyming. There is the comedy: it is weird to rhyme weird / disappeared, reckless to rhyme reckless / necklace, and outrageous to rhyme outrageous / contagious.54 And in Goin’ to Acapulco the rhyme what the hell / Taj Mahal mutters “what the hell”. There is the tension, for instance that of a duel in the world of the Western:

But then the crowd began to stamp their feet and the house lights did dim

And in the darkness of the room, there was only Jim and him

(Lily, Rosemary and the Jack of Hearts)

Once “did dim” has set the scene, the two of them stand there: Jim and him, simplicity themselves. And there is the satire: Dylan can sketch a patriotic posturing simply by thrusting forth the jaw of a rhyme with a challenge.

Now Eisenhower, he’s a Russian spy

Lincoln, Jefferson, and that Roosevelt guy

To my knowledge there’s just one man

That’s really a true American:

George Lincoln Rockwell

A true American will pronounce the proud word, juttingly, Americán. You got a problem with that?

Clearly, rhyme is not exactly the same phenomenon on the page as it is when voiced (on stage or on album). On the page, “good” at the line-ending in One Too Many Mornings is likely to be broadly the same in its pronunciation (though not necessarily in its tone, and this affects pronunciation) as the same word, “good”, at the line-ending two lines later. But in singing, Dylan can play what his voice may do (treat them very differently) against their staying the same: the word both is and is not the one that you heard a moment earlier. Or take “I don’t want to be hers, I want to be yours” (I Wanna Be Your Lover). On the page, no rhyme; in the song, “yers”, which both is and is not a persuasive retort to, or equivalent of, “hers”, both does and does not enjoy the same rights. The first rhyme in Got My Mind Made Up, long / wrong, has an effect that it could never have on the page, since Dylan sings “wrong” so differently from how he sang “long”. There is something very right about this, which depends upon comprehending the way in which the multimedia art of song differs from the page’s poetry.

Other favourites. The rhyme in Talkin’ World War III Blues, “ouch” up against “psychiatric couch”.

I said, “Hold it, Doc, a World War passed through my brain”

He said, “Nurse, get your pad, the boy’s insane”

He grabbed my arm, I said “Ouch!”

As I landed on the psychiatric couch

He said, “Tell me about it”

Ouch: no amount of plump cushioning can remove the pain that psychiatry exists to deal with – and that psychiatry in due course has its own inflictions of. (There’s a moment in the film Panic when the doleful hit-man played by William H. Macy is asked by the shrink as he leaves – after paying $125 for not many minutes – how he is feeling now? “Poor.”) Dylan’s word “pad” plays its small comic part; to write on, not like the padded couch (not padded enough: Ouch!) or the padded cell. Ouch / couch is a rhyme that is itself out to grab you, and that knows the difference between “Tell me about it” as a soothing professional solicitation and as a cynical boredom. Moreover, rhyme is a to-and-fro, an exchange, itself a form of this “I said” / “He said” business or routine.

Another rhyme that has spirit: “nonchalant” against “It’s your mind that I want” in Rita May:

Rita May, Rita May

You got your body in the way

You’re so damned nonchalant

It’s your mind that I want

You don’t have to believe him (I wouldn’t, if I were you, Rita May), but “nonchalant” arriving at “want” is delicious, because nonchalant is so undesiring of her, so cool, so not in heat.

Or there’s the rhyme in Mozambique of “Mozambique” with “cheek to cheek” (along with “cheek” cheekily rhyming with “cheek” there, a perfect fit). There’s always something strange about place names, or persons’ names, rhyming, for they don’t seem to be words exactly, or at any rate are very different kinds of word from your usual word.55

My favourite of all Dylan’s rhymes is another that turns upon a place name, the rhyme of “Utah” with “me ‘Pa’”, as if “U–” in Utah were spelt y o u:

Build me a cabin in Utah

Marry me a wife, catch rainbow trout

Have a bunch of kids who call me “Pa”

That must be what it’s all about

(Sign on the Window)

That’s not a rhyme of “tah” and “pa”, it’s a rhyme of “Utah” and “me ‘Pa’” – like “Me Tarzan, You Jane”. And it has a further dimension of sharp comedy in that Dylan has taken over for his peaceful pastoral purposes a military drill, words to march by – you can hear them being chanted in Frederick Wiseman’s documentary Basic Training (1971):

And now I’ve got

A mother-in-law

And fourteen kids

That call me “Pa”

Yet there is pathos as well as comedy in Sign on the Window, for the Utah stanza is the closing one of a song of loss that begins “Sign on the window says ‘Lonely’”. But then “lonely” is perhaps the loneliest word in the language. For the only rhyme for “lonely” is “only”. Compounding the lonely, Dylan sings it so that it finds its direction home:

You’ve gone to the finest school all right, Miss Lonely

But you know you only used to get juiced in it

(Like a Rolling Stone)

Dylan knows the strain that has to be felt if you want even to be in the vicinity of finding another rhyme for “lonely”:

Sign on the window says “Lonely”

Sign on the door said “No Company Allowed”

Sign on the street says “Y’ Don’t Own Me”

Sign on the porch says “Three’s A Crowd”

Sign on the porch says “Three’s A Crowd”

(Sign on the Window)

Lonely / Y’ Don’t Own Me. No Company Allowed? Company is inherent in rhyming, where one word keeps company with another. And rhyme, like any metaphor, is itself a threesome, though not a crowd: tenor, vehicle, and the union of the two that constitutes the third thing, metaphor.

Arthur Hallam, Tennyson’s friend in whose memory In Memoriam was written, referred to rhyme as “the recurrence of termination”. A fine paradox, for how can termination recur? Can this really be the end when there is a rhyme to come?

Rhyme has been said to contain in itself a constant appeal to Memory and Hope. This is true of all verse, of all harmonized sound; but it is certainly made more palpable by the recurrence of termination. The dullest senses can perceive an identity in that, and be pleased with it; but the partial identity, latent in more diffused resemblances, requires, in order to be appreciated, a soul susceptible of musical impression. The ancients disdained a mode of pleasure, in appearance so little elevated, so ill adapted for effects of art; but they knew not, and with their metrical harmonies, perfectly suited, as these were, to their habitual moods of feeling, they were not likely to know the real capacities of this apparently simple and vulgar combination.56

Rhyme contains this appeal to Memory and Hope (is a container for it, and contains it as you might contain your anger, your laughter, or your drink) because when you have the first rhyme-word you are hoping for the later one, and when you have the later one, you remember the promise that was given earlier and is now fulfilled. Responsibilities on both sides, responsively granted.

So rhyme is intimately involved with lyric – Swinburne insisted on this, back in 1867: “Rhyme is the native condition of lyric verse in English: a rhymeless lyric is a maimed thing.” There are few good unrhymed lyrics of any kind because of the strong filament between lyricism, hope, and memory.57

Dylan loves rhyming on the word “memory” (and rhyme is one of the best aids to memory, is the mnemonic device: “Thirty days hath September, / April, June, and November . . .”). The line in Sad-Eyed Lady of the Lowlands, “With your sheet-metal memory of Cannery Row”, rings true because of the memory within this song that takes you back to the phrase “your sheets like metal”, and because of the curious undulation that can be heard, and is memorable, in “memory” and “Cannery”. And Cannery Row is itself a memory, since the allusion to John Steinbeck’s novel has to be a memory that the singer shares with his listeners, or else it couldn’t work as an allusion.

As for rhyming on “forget”: True Love Tends to Forget, aware that rhyming depends on memory, has “forget” begin in the arms of “regret”, and end, far out, in “Tibet”. The Dylai Lama. And True Love Tends to Forget rhymes “again” and “when”, enacting what the song is talking about, for rhyme is an again / when. And rhyme may be a kind of loving, two things becoming one, yet not losing their own identity.

Or there is Dylan’s loving to rhyme, as all the poets have loved to do, on the word “free”. If Dogs Run Free does little else than gambol with the rhyme (but what a good deal that proves to be). Or there are “free” and “memory” in Mr. Tambourine Man.

Yes, to dance beneath the diamond sky with one hand waving free

Silhouetted by the sea, circled by the circus sands

With all memory and fate driven deep beneath the waves

Let me forget about today until tomorrow

There the word “free” can conjure up a freedom that is not irresponsible, and “memory” asks you not to forget, but to have in mind – whether consciously or not – another element of the rhyme: trustworthy memory.

Dylan wouldn’t have had to learn these stops and steps of the mind from previous poets, since the effect would be the same whether the parallel is a source or an analogue.58 But Dylan is drawing on the same sources of power, when he sings in Abandoned Love:

I march in the parade of liberty

But as long as I love you, I’m not free

– as was John Milton when he protested against irresponsible protesters:

That bawl for freedom in their senseless mood,

And still revolt when truth would set them free.

Licence they mean when they cry liberty.

(Sonnet XII)

Licence is different from liberty, don’t forget – and Milton makes this real to us, by rhyming “free” with “liberty”. Licence is not rhymed by Milton (though it grates against “senseless”), and is sullen about rhyming at all. Does it rhyme? In a word, no? But whatever Milton’s sense of the matter, my sense is that he would never have sunk to poetic licence, though Dylan could well have risen to it.

What did Milton himself mean by “Licence they mean when they cry liberty”? That true freedom acknowledges responsibility. The choice is always between the good kind of bonds and the bad kind, not the choice of some chimerical world that is without bonds. That would be licence. D. H. Lawrence warned against idolizing freedom, happily alive to rhyming in his prose even as poetry is: “Thank God I’m not free, any more than a rooted tree is free.”

Milton described his choice of blank verse for his epic as “an example set, the first in English, of ancient liberty recovered to heroic poem from the troublesome and modern bondage of rhyming”. But he knew that there are such things as good bonds, and he valued rhymes all the more because he knew that their effect could be all the greater if not every single line had to rhyme. T. S. Eliot began the final paragraph of his Reflections on “Vers Libre” (1917): “And this liberation from rhyme might be as well a liberation of rhyme. Freed from its exacting task of supporting lame verse, it could be applied with greater effect where it is most needed.”59

A particular pleasure attaches to rhyming on the word “rhyme”.60 Keats:

Just like that bird am I in loss of time

Whene’er I venture on the stream of rhyme

(To Charles Cowden Clarke)61

The beginning of Sad-Eyed Lady of the Lowlands is superb in what it does with its first three rhyme-words, as simple as can be in the mystery of such spells, three by three, with the triple rhymes interlacing assonantally with the triple “like” (eyes like / like rhymes / like chimes):

With your mercury mouth in the missionary times

And your eyes like smoke and your prayers like rhymes

And your silver cross, and your voice like chimes

Oh, who among them do they think could bury you?

“Times”, “rhymes”, and “chimes” are rhymes because they are chimes that come several times. (“And your eyes like smoke”: a chime from Smoke Gets in Your Eyes.) “Your prayers like rhymes”: rhymes being like prayers because of what it is to trust in an answer to one’s prayer. With his voicing, Dylan does what the seventeenth-century poet Abraham Cowley did with different rhythmical weightings for this same triplet of rhymes in his Ode: Upon Liberty. “If life should a well-ordered poem be”, then it should avoid monotony:

The matter shall be grave, the numbers loose and free.

It shall not keep one setled pace of time,

In the same tune it shall not always chime,

Nor shall each day just to his neighbour rhime.

Sad-Eyed Lady of the Lowlands uses the rhyme on rhyme poignantly. You’re Gonna Make Me Lonesome When You Go uses it ruefully, in singing of “Crickets talking back and forth in rhyme”. For all rhyme is a form of talking back and forth, something that crickets are in a particularly good position to understand, rubbing back and forth, stridulating away. “I could stay with you forever and never realize the time”: that is Dylan’s rhyming line upon rhyme, and this is the way in which the loving thought is realized. “Forever” is so entirely positive, but then so, on this occasion, is the negative word with which it rhymes, “never”.

Even as a yearning is realized – which is not the same as a hope being realized in actuality – in Highlands:

Well my heart’s in the Highlands wherever I roam

That’s where I’ll be when I get called home

The wind, it whispers to the buckeyed trees in rhyme

Well my heart’s in the Highlands

I can only get there one step at a time

The whisper here rises to a determination when “time” comes, in due time, to consummate the rhyme with “rhyme”; and furthermore when “roam” finds itself not only rhyming with “home” (“roam” takes you away – “wherever I roam” – but “home” calls you home again) but when “roam” is rotated into “rhyme”, a tender turn. But then rhyme, too, works “one step at a time”, the feet being metrical. Hopkins:

His sheep seem’d to come from it as they stept,

One and then one, along their walks, and kept

Their changing feet in flicker all the time

And to their feet the narrow bells gave rhyme.

(Richard)

Like Hopkins, Dylan fits together rhymes in favour of rhyme. In the seventeenth century Ben Jonson notoriously, in mock self-contradiction, gave the world A Fit of Rhyme against Rhyme. Dylan is well aware of the hostility that rhymes can evoke, in readers (or listeners), and between the rhymes themselves. For although there is a place where rhymes can whisper (think of it as the Highlands), there are ugly places where rhyme needs to grate hideously, to make you yearn to break free, to change:

You’ve had enough hatred

Your bones are breaking, can’t find nothing sacred

(Ye Shall Be Changed)

Dylan can be a master of war. The friction of “hatred” against “sacred” sets your teeth on edge, or makes you grit them. “You know Satan sometimes comes as a man of peace.”

Rhyme can give shape to individual lines and to a song or poem as a whole, which is where rhyme-schemes come in. A change in the rhyming pattern can intimate that the song or the poem is having to draw to a close, is fulfilling its arc. Life is short, art is long: true, but art is not interminable. Think back to early days with Dylan’s endings, and to how he chose to end Just Like Tom Thumb’s Blues. The last two lines:

I’m going back to New York City

I do believe I’ve had enough

End of song. And it feels like a due ending for the perfectly simple reason that, in this final verse (one that, in closing, starts out “I started out”), all the lines (odd and even) rhyme – something that is not true of any previous verses.

I started out on burgundy

But soon hit the harder stuff

Everybody said they’d stand behind me

When the game got rough

But the joke was on me

There was nobody even there to call my bluff

I’m going back to New York City

I do believe I’ve had enough

The other verses rhyme only the even lines. You don’t have to be conscious of it, but it works on your ear to tell you that there’s something different about this final verse: all its lines are rhyming away. Whether or not you consciously record this, you register it. An ending, not a stopping. And (“I’m going back to New York City”) it has an allusive comic relation to his first album, where the first of his own two songs, Talking New York, has as its ending:

So long, New York

Howdy, East Orange

Why was that such a wittily wry ending? First, because of the Orange as against an apple. New York is the Big Apple, so there’s a subterranean semantic rhyming going on, sense rather than sound, Big Apple versus East Orange. But the ending depends, too, upon the fact that “orange” famously is a word that does not have a rhyme in English. Dylan was asked once about this:

Do you have a rhyme for “orange”?

“What, I didn’t hear that.”

A rhyme for “orange”.

“A-ha . . . just a rhyme for ‘orange’?”

It is true you were censored for singing on the “Ed Sullivan Show”?

“I’ll tell you the rhyme in a minute.”62

Apple, on the other hand, is easy as pie. Dylan uses the awry feeling at the particular part of such a blues song, where the last throw-away moment throws away rhyme, and goes in instead for a sloping-off movement. “Howdy, East Orange”. So long, rhyme.

The reason that Andrew Marvell’s lines about the orange are so delectable is that the poetical inversion is not lapsed into, but called for:

He hangs in shades the orange bright,

Like golden lamps in a green night.

(Bermudas)

The inversion of “the orange bright” is justified by there not being a rhyme for orange anyway, and if Marvell had said, “He hangs in shades the bright orange”, he’d have had to set out for a mountain range a long way from Bermuda. (That’s right, Blorenge, in Wales.) Even the great rhymester Robert Browning never ventured to end a line of verse with the word “orange”.

There’s a deft comedy that Dylan avails himself of here, in making something from the simple fact that some words do and other words don’t rhyme. True, the voice that exults in forcing “hers” into rhyming rapport with “yours” (“I don’t wanna be hers, I wanna be yers”) is one that never rests when it comes to wresting and wrestling, but there are limits . . .

Emotionally Yours: the phrase signs off, the usual formula unusually worded and unusually used. The song takes the great commonplaces of rhyme and makes them not quite what you would have expected. But then love is like that in its comings and goings. The first rhyme in Emotionally Yours is find me / remind me – itself a reminder that every rhyme is an act of finding and of reminding (that’s what a rhyme is, after all). Later there is rock me / lock me, this not locked into position (no feeling of being trapped), and with “rock me” – “Come baby, rock me” – having the lilt of a lullaby, not the drive of rock. It’s a song about how someone can be indeed “emotionally yours” but not yours in every way (not domestically, for instance – not available for marriage, for who knows what reasons?). Every verse signs off, as if in a letter at once intimate, cunning, and formal, “be emotionally yours”. Dylan sings it with a full sense that it is a deep pastiche of a good old old-time song, with stately exaggerated movements of his voice, especially at the rhymes – and he makes it new.

And how does this song, A Valediction: forbidding Mourning, like John Donne’s great poem about absence, end so that we are “satisfied”? Satisfied that though the song ends, the gratitude doesn’t. Again it’s the rhyming that realizes the song’s story. After a clear pattern:

find me / remind me

show me / know me

rock me / lock me

teach me / reach me

– after these:

Come baby, shake me, come baby, take me, I would be satisfied

Come baby, hold me, come baby, help me, my arms are open wide

I could be unraveling wherever I’m traveling, even to foreign shores

But I will always be emotionally yours

Shake me / take me: this is unexpected only in the benign impulse recognized in “shake” there. And unraveling / traveling: this is unexpected only in its sudden twinge of darkness. “As he lay unravelling in the agony of death, the standers-by could hear him say softly, ‘I have seen the glories of the world.’”63 But hold me / help me? How easily “Come baby, hold me” could have slid equably into “come baby, fold me”, with “my arms are open wide” simply waiting there to do the folding. But “Come baby, hold me, come baby, help me”: the rotating of “hold me” into that unexpected calm plea, at once central and at a tangent, “help me”. The turn has the poignancy of Christina Rossetti, who thanks the Lord For a Mercy Received:

Till now thy hand hath held me fast

Lord, help me, hold me, to the last.64

To the last. Will always be more-than-emotionally Yours. The thought lightens her darkness and ours.

In the lightness of a Doonesbury strip there was an exchange that enjoyed its comedy not exactly at Dylan’s expense (Jimmy Carter is the one who is quoted) but on his account:

– “An authentic American voice!” Can you beat that, Jim? I mean, I just want it to rhyme, man.

– Now he tells us.

Not so much “Now he tells us” as How he tells us, or rather How he does more than just tell us. Show and Tell. Anyway, Dylan himself has been happy to convey the ways in which rhyme, among the many things that it can be, can be fun.

Is rhyming fun for you?

“Well, it can be, but you know, it’s a game. You know, you sit around . . . It gives you a thrill. It gives you a thrill to rhyme something you might think, well, that’s never been rhymed before.”65

an’ new ideas that haven’t been wrote

an’ new words t’ fit into rhyme

(if it rhymes, it rhymes

if it don’t, it don’t

if it comes, it comes

if it won’t, it won’t)66

Robert Shelton had recourse to a rhyme of a sort when he put it that “Dylan pretends to know more about freight trains than quatrains.” Dylan, years later, spoke of what he knows:

“As you get older, you get smarter and that can hinder you because you try to gain control over the creative impulse. Creativity is not like a freight train going down the tracks. It’s something that has to be caressed and treated with a great deal of respect. If your mind is intellectually in the way, it will stop you. You’ve got to program your brain not to think too much.”

And how do you do that?

“Go out with the bird dogs.”67

What is at issue is not pretence but premeditation. Dylan is conscious of how much needs to be done by the unconscious or subconscious.

Still staying in the unconscious frame of mind, you can pull yourself out and throw up two rhymes first and work it back. You get the rhymes first and work it back and then see if you make it make sense in another kind of way. You can still stay in the unconscious frame of mind to pull it off, which is the state of mind you have to be in anyway.68

Georg Christoph Lichtenberg, the aphorist and sage, believed that artists both do and do not know what they are doing, and that their works are even wiser than they are. “The metaphor is much more subtle than its inventor.”69

There’s a lyric in “License to Kill”: “Man has invented his doom / First step was touching the moon”. Do you really believe that?

“Yeah, I do. I have no idea why I wrote that line, but on some level, it’s just like a door into the unknown.”70