Читать книгу The Lost Road and Other Writings - Christopher Tolkien - Страница 10

ОглавлениеIII

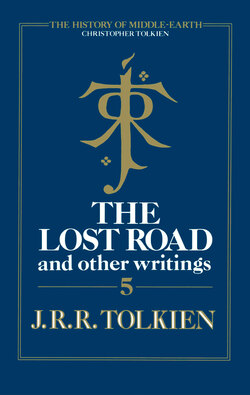

THE LOST ROAD

(i)

The opening chapters

For the texts of The Lost Road and its relation to The Fall of Númenor see pp. 8–9. I give here the two completed chapters at the beginning of the work, following them with a brief commentary.

Chapter I

A Step Forward. Young Alboin *

‘Alboin! Alboin!’

There was no answer. There was no one in the play-room.

‘Alboin!’ Oswin Errol stood at the door and called into the small high garden at the back of his house. At length a young voice answered, sounding distant and like the answer of someone asleep or just awakened.

‘Yes?’

‘Where are you?’

‘Here!’

‘Where is “here”?’

‘Here: up on the wall, father.’

Oswin sprang down the steps from the door into the garden, and walked along the flower-bordered path. It led after a turn to a low stone wall, screened from the house by a hedge. Beyond the stone wall there was a brief space of turf, and then a cliff-edge, beyond which outstretched, and now shimmering in a calm evening, the western sea. Upon the wall Oswin found his son, a boy about twelve years old, lying gazing out to sea with his chin in his hands.

‘So there you are!’ he said. ‘You take a deal of calling. Didn’t you hear me?’

‘Not before the time when I answered,’ said Alboin.

‘Well, you must be deaf or dreaming,’ said his father. ‘Dreaming, it looks like. It is getting very near bed-time; so, if you want any story tonight, we shall have to begin at once.’

‘I am sorry, father, but I was thinking.’

‘What about?’

‘Oh, lots of things mixed up: the sea, and the world, and Alboin.’

‘Alboin?’

‘Yes. I wondered why Alboin. Why am I called Alboin? They often ask me “Why Alboin?” at school, and they call me All-bone. But I am not, am I?’

‘You look rather bony, boy; but you are not all bone, I am glad to say. I am afraid I called you Alboin, and that is why you are called it. I am sorry: I never meant it to be a nuisance to you.’

‘But it is a real name, isn’t it?’ said Alboin eagerly. ‘I mean, it means something, and men have been called it? It isn’t just invented?’

‘Of course not. It is just as real and just as good as Oswin; and it belongs to the same family, you might say. But no one ever bothered me about Oswin. Though I often used to get called Oswald by mistake. I remember how it used to annoy me, though I can’t think why. I was rather particular about my name.’

They remained talking on the wall overlooking the sea; and did not go back into the garden, or the house, until bed-time. Their talk, as often happened, drifted into story-telling; and Oswin told his son the tale of Alboin son of Audoin, the Lombard king; and of the great battle of the Lombards and the Gepids, remembered as terrible even in the grim sixth century; and of the kings Thurisind and Cunimund, and of Rosamunda. ‘Not a good story for near bed-time,’ he said, ending suddenly with Alboin’s drinking from the jewelled skull of Cunimund.

‘I don’t like that Alboin much,’ said the boy. ‘I like the Gepids better, and King Thurisind. I wish they had won. Why didn’t you call me Thurisind or Thurismod?’

‘Well, really mother had meant to call you Rosamund, only you turned up a boy. And she didn’t live to help me choose another name, you know. So I took one out of that story, because it seemed to fit. I mean, the name doesn’t belong only to that story, it is much older. Would you rather have been called Elf-friend? For that’s what the name means.’

‘No-o,’ said Alboin doubtfully. ‘I like names to mean something, but not to say something.’

‘Well, I might have called you Ælfwine, of course; that is the Old English form of it. I might have called you that, not only after Ælfwine of Italy, but after all the Elf-friends of old; after Ælfwine, King Alfred’s grandson, who fell in the great victory in 937, and Ælfwine who fell in the famous defeat at Maldon, and many other Englishmen and northerners in the long line of Elf-friends. But I gave you a latinized form. I think that is best. The old days of the North are gone beyond recall, except in so far as they have been worked into the shape of things as we know it, into Christendom. So I took Alboin; for it is not Latin and not Northern, and that is the way of most names in the West, and also of the men that bear them. I might have chosen Albinus, for that is what they sometimes turned the name into; and it wouldn’t have reminded your friends of bones. But it is too Latin, and means something in Latin. And you are not white or fair, boy, but dark. So Alboin you are. And that is all there is to it, except bed.’ And they went in.

But Alboin looked out of his window before getting into bed; and he could see the sea beyond the edge of the cliff. It was a late sunset, for it was summer. The sun sank slowly to the sea, and dipped red beyond the horizon. The light and colour faded quickly from the water: a chilly wind came up out of the West, and over the sunset-rim great dark clouds sailed up, stretching huge wings southward and northward, threatening the land.

‘They look like the eagles of the Lord of the West coming upon Númenor,’ Alboin said aloud, and he wondered why. Though it did not seem very strange to him. In those days he often made up names. Looking on a familiar hill, he would see it suddenly standing in some other time and story: ‘the green shoulders of Amon-ereb,’ he would say. ‘The waves are loud upon the shores of Beleriand,’ he said one day, when storm was piling water at the foot of the cliff below the house.

Some of these names were really made up, to please himself with their sound (or so he thought); but others seemed ‘real’, as if they had not been spoken first by him. So it was with Númenor. ‘I like that,’ he said to himself. ‘I could think of a long story about the land of Númenor.’

But as he lay in bed, he found that the story would not be thought. And soon he forgot the name; and other thoughts crowded in, partly due to his father’s words, and partly to his own day-dreams before.

‘Dark Alboin,’ he thought. ‘I wonder if there is any Latin in me. Not much, I think. I love the western shores, and the real sea – it is quite different from the Mediterranean, even in stories. I wish there was no other side to it. There were darkhaired people who were not Latins. Are the Portuguese Latins? What is Latin? I wonder what kind of people lived in Portugal and Spain and Ireland and Britain in old days, very old days, before the Romans, or the Carthaginians. Before anybody else. I wonder what the man thought who was the first to see the western sea.’

Then he fell asleep, and dreamed. But when he woke the dream slipped beyond recall, and left no tale or picture behind, only the feeling that these had brought: the sort of feeling Alboin connected with long strange names. And he got up. And summer slipped by, and he went to school and went on learning Latin.

Also he learned Greek. And later, when he was about fifteen, he began to learn other languages, especially those of the North: Old English, Norse, Welsh, Irish. This was not much encouraged – even by his father, who was an historian. Latin and Greek, it seemed to be thought, were enough for anybody; and quite old-fashioned enough, when there were so many successful modern languages (spoken by millions of people); not to mention maths and all the sciences.

But Alboin liked the flavour of the older northern languages, quite as much as he liked some of the things written in them. He got to know a bit about linguistic history, of course; he found that you rather had it thrust on you anyway by the grammar-writers of ‘unclassical’ languages. Not that he objected: sound-changes were a hobby of his, at the age when other boys were learning about the insides of motor-cars. But, although he had some idea of what were supposed to be the relationships of European languages, it did not seem to him quite all the story. The languages he liked had a definite flavour – and to some extent a similar flavour which they shared. It seemed, too, in some way related to the atmosphere of the legends and myths told in the languages.

One day, when Alboin was nearly eighteen, he was sitting in the study with his father. It was autumn, and the end of summer holidays spent mostly in the open. Fires were coming back. It was the time in all the year when book-lore is most attractive (to those who really like it at all). They were talking ‘language’. For Errol encouraged his boy to talk about anything he was interested in; although secretly he had been wondering for some time whether Northern languages and legends were not taking up more time and energy than their practical value in a hard world justified. ‘But I had better know what is going on, as far as any father can,’ he thought. ‘He’ll go on anyway, if he really has a bent – and it had better not be bent inwards.’

Alboin was trying to explain his feeling about ‘language-atmosphere’. ‘You get echoes coming through, you know,’ he said, ‘in odd words here and there – often very common words in their own language, but quite unexplained by the etymologists; and in the general shape and sound of all the words, somehow; as if something was peeping through from deep under the surface.’

‘Of course, I am not a philologist,’ said his father; ‘but I never could see that there was much evidence in favour of ascribing language-changes to a substratum. Though I suppose underlying ingredients do have an influence, though it is not easy to define, on the final mixture in the case of peoples taken as a whole, different national talents and temperaments, and that sort of thing. But races, and cultures, are different from languages.’

‘Yes,’ said Alboin; ‘but very mixed up, all three together. And after all, language goes back by a continuous tradition into the past, just as much as the other two. I often think that if you knew the living faces of any man’s ancestors, a long way back, you might find some queer things. You might find that he got his nose quite clearly from, say, his mother’s great-grandfather; and yet that something about his nose, its expression or its set or whatever you like to call it, really came down from much further back, from, say, his father’s great-great-great-grandfather or greater. Anyway I like to go back – and not with race only, or culture only, or language; but with all three. I wish I could go back with the three that are mixed in us, father; just the plain Errols, with a little house in Cornwall in the summer. I wonder what one would see.’

‘It depends how far you went back,’ said the elder Errol. ‘If you went back beyond the Ice-ages, I imagine you would find nothing in these parts; or at any rate a pretty beastly and uncomely race, and a tooth-and-nail culture, and a disgusting language with no echoes for you, unless those of food-noises.’

‘Would you?’ said Alboin. ‘I wonder.’

‘Anyway you can’t go back,’ said his father; ‘except within the limits prescribed to us mortals. You can go back in a sense by honest study, long and patient work. You had better go in for archaeology as well as philology: they ought to go well enough together, though they aren’t joined very often.’

‘Good idea,’ said Alboin. ‘But you remember, long ago, you said I was not all-bone. Well, I want some mythology, as well. I want myths, not only bones and stones.’

‘Well, you can have ’em! Take the whole lot on!’ said his father laughing. ‘But in the meanwhile you have a smaller job on hand. Your Latin needs improving (or so I am told), for school purposes. And scholarships are useful in lots of ways, especially for folk like you and me who go in for antiquated subjects. Your first shot is this winter, remember.’

‘I wish Latin prose was not so important,’ said Alboin. ‘I am really much better at verses.’

‘Don’t go putting any bits of your Eressëan, or Elf-latin, or whatever you call it, into your verses at Oxford. It might scan, but it wouldn’t pass.’

‘Of course not!’ said the boy, blushing. The matter was too private, even for private jokes. ‘And don’t go blabbing about Eressëan outside the partnership,’ he begged; ‘or I shall wish I had kept it quiet.’

‘Well, you did pretty well. I don’t suppose I should ever have heard about it, if you hadn’t left your note-books in my study. Even so I don’t know much about it. But, my dear lad, I shouldn’t dream of blabbing, even if I did. Only don’t waste too much time on it. I am afraid I am anxious about that schol[arship], not only from the highest motives. Cash is not too abundant.’

‘Oh, I haven’t done anything of that sort for a long while, at least hardly anything,’ said Alboin.

‘It isn’t getting on too well, then?’

‘Not lately. Too much else to do, I suppose. But I got a lot of jolly new words a few days ago: I am sure lōmelindë means nightingale, for instance, and certainly lōmë is night (though not darkness). The verb is very sketchy still. But –’ He hesitated. Reticence (and uneasy conscience) were at war with his habit of what he called ‘partnership with the pater’, and his desire to unbosom the secret anyway. ‘But, the real difficulty is that another language is coming through, as well. It seems to be related but quite different, much more – more Northern. Alda was a tree (a word I got a long time ago); in the new language it is galadh, and orn. The Sun and Moon seem to have similar names in both: Anar and Isil beside Anor and Ithil. I like first one, then the other, in different moods. Beleriandic is really very attractive; but it complicates things.’

‘Good Lord!’ said his father, ‘this is serious! I will respect unsolicited secrets. But do have a conscience as well as a heart, and – moods. Or get a Latin and Greek mood!’

‘I do. I have had one for a week, and I have got it now; a Latin one luckily, and Virgil in particular. So here we part.’ He got up. ‘I am going to do a bit of reading. I’ll look in when I think you ought to go to bed.’ He closed the door on his father’s snort.

As a matter of fact Errol did not really like the parting shot. The affection in it warmed and saddened him. A late marriage had left him now on the brink of retirement from a schoolmaster’s small pay to his smaller pension, just when Alboin was coming of University age. And he was also (he had begun to feel, and this year to admit in his heart) a tired man. He had never been a strong man. He would have liked to accompany Alboin a great deal further on the road, as a younger father probably would have done; but he did not somehow think he would be going very far. ‘Damn it,’ he said to himself, ‘a boy of that age ought not to be thinking such things, worrying whether his father is getting enough rest. Where’s my book?’

Alboin in the old play-room, turned into junior study, looked out into the dark. He did not for a long time turn to books. ‘I wish life was not so short,’ he thought. ‘Languages take such a time, and so do all the things one wants to know about. And the pater, he is looking tired. I want him for years. If he lived to be a hundred I should be only about as old as he is now. and I should still want him. But he won’t. I wish we could stop getting old. The pater could go on working and write that book he used to talk about, about Cornwall; and we could go on talking. He always plays up, even if he does not agree or understand. Bother Eressëan. I wish he hadn’t mentioned it. I am sure I shall dream tonight; and it is so exciting. The Latin-mood will go. He is very decent about it, even though he thinks I am making it all up. If I were, I would stop it to please him. But it comes, and I simply can’t let it slip when it does. Now there is Beleriandic.’

Away west the moon rode in ragged clouds. The sea glimmered palely out of the gloom, wide, flat, going on to the edge of the world. ‘Confound you, dreams!’ said Alboin. ‘Lay off, and let me do a little patient work at least until December. A schol[arship] would brace the pater.’

He found his father asleep in his chair at half past ten. They went up to bed together. Alboin got into bed and slept with no shadow of a dream. The Latin-mood was in full blast after breakfast; and the weather allied itself with virtue and sent torrential rain.

Chapter II

Alboin and Audoin

Long afterwards Alboin remembered that evening, that had marked the strange, sudden, cessation of the Dreams. He had got a scholarship (the following year) and had ‘braced the pater’. He had behaved himself moderately well at the university – not too many side-issues (at least not what he called too many); though neither the Latin nor the Greek mood had remained at all steadily to sustain him through ‘Honour Mods.’ They came back, of course, as soon as the exams were over. They would. He had switched over, all the same, to history, and had again ‘braced the pater’ with a ‘first-class’. And the pater had needed bracing. Retirement proved quite different from a holiday: he had seemed just to slip slowly out. He had hung on just long enough to see Alboin into his first job: an assistant lecturership in a university college.

Rather disconcertingly the Dreams had begun again just before ‘Schools’, and were extraordinarly strong in the following vacation – the last he and his father had spent together in Cornwall. But at that time the Dreams had taken a new turn, for a while.

He remembered one of the last conversations of the old pleasant sort he had been able to have with the old man. It came back clearly to him now.

‘How’s the Eressëan Elf-latin, boy?’ his father asked, smiling, plainly intending a joke, as one may playfully refer to youthful follies long atoned for.

‘Oddly enough,’ he answered, ‘that hasn’t been coming through lately. I have got a lot of different stuff. Some is beyond me, yet. Some might be Celtic, of a sort. Some seems like a very old form of Germanic; pre-runic, or I’ll eat my cap and gown.’

The old man smiled, almost raised a laugh. ‘Safer ground, boy, safer ground for an historian. But you’ll get into trouble, if you let your cats out of the bag among the philologists – unless, of course, they back up the authorities.’

‘As a matter of fact, I rather think they do,’ he said.

‘Tell me a bit, if you can without your note-books,’ his father slyly said.

‘Westra lage wegas rehtas, nu isti sa wraithas.’ He quoted that, because it had stuck in his mind, though he did not understand it. Of course the mere sense was fairly plain: a straight road lay westward, now it is bent. He remembered waking up, and feeling it was somehow very significant. ‘Actually I got a bit of plain Anglo-Saxon last night,’ he went on. He thought Anglo-Saxon would please his father; it was a real historical language, of which the old man had once known a fair amount. Also the bit was very fresh in his mind, and was the longest and most connected he had yet had. Only that very morning he had waked up late, after a dreamful night, and had found himself saying the lines. He jotted them down at once, or they might have vanished (as usual) by breakfast-time, even though they were in a language he knew. Now waking memory had them secure.

‘Thus cwæth Ælfwine Wídlást:

Fela bith on Westwegum werum uncúthra

wundra and wihta, wlitescéne land,

eardgeard elfa, and ésa bliss.

Lýt ǽnig wát hwylc his longath síe

thám the eftsíthes eldo getwǽfeth.’

His father looked up and smiled at the name Ælfwine. He translated the lines for him; probably it was not necessary, but the old man had forgotten many other things he had once known much better than Anglo-Saxon.

‘Thus said Ælfwine the far-travelled: “There is many a thing in the West-regions unknown to men, marvels and strange beings, a land fair and lovely, the homeland of the Elves, and the bliss of the Gods. Little doth any man know what longing is his whom old age cutteth off from return.”’

He suddenly regretted translating the last two lines. His father looked up with an odd expression. ‘The old know,’ he said. ‘But age does not cut us off from going away, from – from forthsith. There is no eftsith: we can’t go back. You need not tell me that. But good for Ælfwine-Alboin. You could always do verses.’

Damn it – as if he would make up stuff like that, just to tell it to the old man, practically on his death-bed. His father had, in fact, died during the following winter.

On the whole he had been luckier than his father; in most ways, but not in one. He had reached a history professorship fairly early; but he had lost his wife, as his father had done, and had been left with an only child, a boy, when he was only twenty-eight.

He was, perhaps, a pretty good professor, as they go. Only in a small southern university, of course, and he did not suppose he would get a move. But at any rate he wasn’t tired of being one; and history, and even teaching it, still seemed interesting (and fairly important). He did his duty, at least, or he hoped so. The boundaries were a bit vague. For, of course, he had gone on with the other things, legends and languages – rather odd for a history professor. Still there it was: he was fairly learned in such book-lore, though a lot of it was well outside the professional borders.

And the Dreams. They came and went. But lately they had been getting more frequent, and more – absorbing. But still tantalizingly linguistic. No tale, no remembered pictures; only the feeling that he had seen things and heard things that he wanted to see, very much, and would give much to see and hear again – and these fragments of words, sentences, verses. Eressëan as he called it as a boy – though he could not remember why he had felt so sure that that was the proper name – was getting pretty complete. He had a lot of Beleriandic, too, and was beginning to understand it, and its relation to Eressëan. And he had a lot of unclassifiable fragments, the meaning of which in many cases he did not know, through forgetting to jot it down while he knew it. And odd bits in recognizable languages. Those might be explained away, of course. But anyway nothing could be done about them: not publication or anything of that sort. He had an odd feeling that they were not essential: only occasional lapses of forgetfulness which took a linguistic form owing to some peculiarity of his own mental make-up. The real thing was the feeling the Dreams brought more and more insistently, and taking force from an alliance with the ordinary professional occupations of his mind. Surveying the last thirty years, he felt he could say that his most permanent mood, though often overlaid or suppressed, had been since childhood the desire to go back. To walk in Time, perhaps, as men walk on long roads; or to survey it, as men may see the world from a mountain, or the earth as a living map beneath an airship. But in any case to see with eyes and to hear with ears: to see the lie of old and even forgotten lands, to behold ancient men walking, and hear their languages as they spoke them, in the days before the days, when tongues of forgotten lineage were heard in kingdoms long fallen by the shores of the Atlantic.

But nothing could be done about that desire, either. He used to be able, long ago, to talk about it, a little and not too seriously, to his father. But for a long while he had had no one to talk to about that sort of thing. But now there was Audoin. He was growing up. He was sixteen.

He had called his boy Audoin, reversing the Lombardic order. It seemed to fit. It belonged anyway to the same name-family, and went with his own name. And it was a tribute to the memory of his father – another reason for relinquishing Anglo-Saxon Eadwine, or even commonplace Edwin. Audoin had turned out remarkably like Alboin, as far as his memory of young Alboin went, or his penetration of the exterior of young Audoin. At any rate he seemed interested in the same things, and asked the same questions; though with much less inclination to words and names, and more to things and descriptions. Unlike his father he could draw, but was not good at ‘verses’. Nonetheless he had, of course, eventually asked why he was called Audoin. He seemed rather glad to have escaped Edwin. But the question of meaning had not been quite so easy to answer. Friend of fortune, was it, or of fate, luck, wealth, blessedness? Which?

‘I like Aud,’ young Audoin had said – he was then about thirteen – ‘if it means all that. A good beginning for a name. I wonder what Lombards looked like. Did they all have Long Beards?’

Alboin had scattered tales and legends all down Audoin’s childhood and boyhood, like one laying a trail, though he was not clear what trail or where it led. Audoin was a voracious listener, as well (latterly) as a reader. Alboin was very tempted to share his own odd linguistic secrets with the boy. They could at least have some pleasant private fun. But he could sympathize with his own father now – there was a limit to time. Boys have a lot to do.

Anyway, happy thought, Audoin was returning from school tomorrow. Examination-scripts were nearly finished for this year for both of them. The examiner’s side of the business was decidedly the stickiest (thought the professor), but he was nearly unstuck at last. They would be off to the coast in a few days, together.

There came a night, and Alboin lay again in a room in a house by the sea: not the little house of his boyhood, but the same sea. It was a calm night, and the water lay like a vast plain of chipped and polished flint, petrified under the cold light of the Moon. The path of moonlight lay from the shore to the edge of sight.

Sleep would not come to him, although he was eager for it. Not for rest – he was not tired; but because of last night’s Dream. He hoped to complete a fragment that had come through vividly that morning. He had it at hand in a note-book by his bed-side; not that he was likely to forget it once it was written down.

Then there had seemed to be a long gap.

There were one or two new words here, of which he wanted to discover the meaning: it had escaped before he could write it down this morning. Probably they were names: tarkalion was almost certainly a king’s name, for tār was common in royal names. It was curious how often the remembered snatches harped on the theme of a ‘straight road’. What was atalante? It seemed to mean ruin or downfall, but also to be a name.

Alboin felt restless. He left his bed and went to the window. He stood there a long while looking out to sea; and as he stood a chill wind got up in the West. Slowly over the dark rim of sky and water’s meeting clouds lifted huge heads, and loomed upwards, stretching out vast wings, south and north.

‘They look like the eagles of the Lord of the West over Númenor,’ he said aloud, and started. He had not purposed any words. For a moment he had felt the oncoming of a great disaster long foreseen. Now memory stirred, but could not be grasped. He shivered. He went back to bed and lay wondering. Suddenly the old desire came over him. It had been growing again for a long time, but he had not felt it like this, a feeling as vivid as hunger or thirst, for years, not since he was about Audoin’s age.

‘I wish there was a “Time-machine”,’ he said aloud. ‘But Time is not to be conquered by machines. And I should go back, not forward; and I think backwards would be more possible.’

The clouds overcame the sky, and the wind rose and blew; and in his ears, as he fell asleep at last, there was a roaring in the leaves of many trees, and a roaring of long waves upon the shore. ‘The storm is coming upon Númenor!’ he said, and passed out of the waking world.

In a wide shadowy place he heard a voice.

‘Elendil!’ it said. ‘Alboin, whither are you wandering?’

‘Who are you?’ he answered. ‘And where are you?’

A tall figure appeared, as if descending an unseen stair towards him. For a moment it flashed through his thought that the face, dimly seen, reminded him of his father.

‘I am with you. I was of Númenor, the father of many fathers before you. I am Elendil, that is in Eressëan “Elf-friend”, and many have been called so since. You may have your desire.’

‘What desire?’

‘The long-hidden and the half-spoken: to go back.’

‘But that cannot be, even if I wish it. It is against the law.’

‘It is against the rule. Laws are commands upon the will and are binding. Rules are conditions; they may have exceptions.’

‘But are there ever any exceptions?’

‘Rules may be strict, yet they are the means, not the ends, of government. There are exceptions; for there is that which governs and is above the rules. Behold, it is by the chinks in the wall that light comes through, whereby men become aware of the light and therein perceive the wall and how it stands. The veil is woven, and each thread goes an appointed course, tracing a design; yet the tissue is not impenetrable, or the design would not be guessed; and if the design were not guessed, the veil would not be perceived, and all would dwell in darkness. But these are old parables, and I came not to speak such things. The world is not a machine that makes other machines after the fashion of Sauron. To each under the rule some unique fate is given, and he is excepted from that which is a rule to others. I ask if you would have your desire?’

‘I would.’

‘You ask not: how or upon what conditions.’

‘I do not suppose I should understand how, and it does not seem to me necessary. We go forward, as a rule, but we do not know how. But what are the conditions?’

‘That the road and the halts are prescribed. That you cannot return at your wish, but only (if at all) as it may be ordained. For you shall not be as one reading a book or looking in a mirror, but as one walking in living peril. Moreover you shall not adventure yourself alone.’

‘Then you do not advise me to accept? You wish me to refuse out of fear?’

‘I do not counsel, yes or no. I am not a counsellor. I am a messenger, a permitted voice. The wishing and the choosing are for you.’

‘But I do not understand the conditions, at least not the last. I ought to understand them all clearly.’

‘You must, if you choose to go back, take with you Herendil, that is in other tongue Audoin, your son; for you are the ears and he is the eyes. But you may not ask that he shall be protected from the consequences of your choice, save as your own will and courage may contrive.’

‘But I can ask him, if he is willing?’

‘He would say yes, because he loves you and is bold; but that would not resolve your choice.’

‘And when can I, or we, go back?’

‘When you have made your choice.’

The figure ascended and receded. There was a roaring as of seas falling from a great height. Alboin could still hear the tumult far away, even after his waking eyes roamed round the room in the grey light of morning. There was a westerly gale blowing. The curtains of the open window were drenched, and the room was full of wind.

He sat silent at the breakfast-table. His eyes strayed continually to his son’s face, watching his expressions. He wondered if Audoin ever had any Dreams. Nothing that left any memory, it would appear. Audoin seemed in a merry mood, and his own talk was enough for him, for a while. But at length he noticed his father’s silence, unusual even at breakfast.

‘You look glum, father,’ he said. ‘Is there some knotty problem on hand?’

‘Yes – well no, not really,’ answered Alboin. ‘I think I was thinking, among other things, that it was a gloomy day, and not a good end to the holidays. What are you going to do?’

‘Oh, I say!’ exclaimed Audoin. ‘I thought you loved the wind. I do. Especially a good old West-wind. I am going along the shore.’

‘Anything on?’

‘No, nothing special – just the wind.’

‘Well, what about the beastly wind?’ said Alboin, unaccountably irritated.

The boy’s face fell. ‘I don’t know,’ he said. ‘But I like to be in it, especially by the sea; and I thought you did.’ There was a silence.

After a while Audoin began again, rather hesitatingly: ‘Do you remember the other day upon the cliffs near Predannack, when those odd clouds came up in the evening, and the wind began to blow?’

‘Yes,’ said Alboin in an unencouraging tone.

‘Well, you said when we got home that it seemed to remind you of something, and that the wind seemed to blow through you, like, like, a legend you couldn’t catch. And you felt, back in the quiet, as if you had listened to a long tale, which left you excited, though it left absolutely no pictures at all.’

‘Did I?’ said Alboin. ‘I can remember feeling very cold, and being glad to get back to a fire.’ He immediately regretted it, and felt ashamed. For Audoin said no more; though he felt certain that the boy had been making an opening to say something more, something that was on his mind. But he could not help it. He could not talk of such things to-day. He felt cold. He wanted peace, not wind.

Soon after breakfast Audoin went out, announcing that he was off for a good tramp, and would not be back at any rate before tea-time. Alboin remained behind. All day last night’s vision remained with him, something different from the common order of dreams. Also it was (for him) curiously unlinguistic – though plainly related, by the name Númenor, to his language dreams. He could not say whether he had conversed with Elendil in Eressëan or English.

He wandered about the house restlessly. Books would not be read, and pipes would not smoke. The day slipped out of his hand, running aimlessly to waste. He did not see his son, who did not even turn up for tea, as he had half promised to do. Dark seemed to come unduly early.

In the late evening Alboin sat in his chair by the fire. ‘I dread this choice,’ he said to himself. He had no doubt that there was really a choice to be made. He would have to choose, one way or another, however he represented it to himself. Even if he dismissed the Dream as what is called ‘a mere dream’, it would be a choice – a choice equivalent to no.

‘But I cannot make up my mind to no,’ he thought. ‘I think, I am almost sure, Audoin would say yes. And he will know of my choice sooner or later. It is getting more and more difficult to hide my thoughts from him: we are too closely akin, in many ways besides blood, for secrets. The secret would become unbearable, if I tried to keep it. My desire would become doubled through feeling that I might have, and become intolerable. And Audoin would probably feel I had robbed him through funk.

‘But it is dangerous, perilous in the extreme – or so I am warned. I don’t mind for myself. But for Audoin. But is the peril any greater than fatherhood lets in? It is perilous to come into the world at any point in Time. Yet I feel the shadow of this peril more heavily. Why? Because it is an exception to the rules? Or am I experiencing a choice backwards: the peril of fatherhood repeated? Being a father twice to the same person would make one think. Perhaps I am already moving back. I don’t know. I wonder. Fatherhood is a choice, and yet it is not wholly by a man’s will. Perhaps this peril is my choice, and yet also outside my will. I don’t know. It is getting very dark. How loud the wind is. There is storm over Númenor. ‘Alboin slept in his chair.

He was climbing steps, up, up on to a high mountain. He felt, and thought he could hear, Audoin following him, climbing behind him. He halted, for it seemed somehow that he was again in the same place as on the previous night; though no figure could be seen.

‘I have chosen,’ he said. ‘I will go back with Herendil.’

Then he lay down, as if to rest. Half-turning: ‘Good night!’ he murmured. ‘Sleep well, Herendil! We start when the summons comes.’

‘You have chosen,’ a voice said above him. ‘The summons is at hand.’

Then Alboin seemed to fall into a dark and a silence, deep and absolute. It was as if he had left the world completely, where all silence is on the edge of sound, and filled with echoes, and where all rest is but repose upon some greater motion. He had left the world and gone out. He was silent and at rest: a point.

He was poised; but it was clear to him that he had only to will it, and he would move.

‘Whither?’ He perceived the question, but neither as a voice from outside, nor as one from within himself.

‘To whatever place is appointed. Where is Herendil?’

‘Waiting. The motion is yours.’

‘Let us move!’

Audoin tramped on, keeping within sight of the sea as much as he could. He lunched at an inn, and then tramped on again, further than he had intended. He was enjoying the wind and the rain, yet he was filled with a curious disquiet. There had been something odd about his father this morning.

‘So disappointing,’ he said to himself. ‘I particularly wanted to have a long tramp with him to-day. We talk better walking, and I really must have a chance of telling him about the Dreams. I can talk about that sort of thing to my father, if we both get into the mood together. Not that he is usually at all difficult – seldom like to-day. He usually takes you as you mean it: joking or serious; doesn’t mix the two, or laugh in the wrong places. I have never known him so frosty.’

He tramped on. ‘Dreams,’ he thought. ‘But not the usual sort, quite different: very vivid; and though never quite repeated, all gradually fitting into a story. But a sort of phantom story with no explanations. Just pictures, but not a sound, not a word. Ships coming to land. Towers on the shore. Battles, with swords glinting but silent. And there is that ominous picture: the great temple on the mountain, smoking like a volcano. And that awful vision of the chasm in the seas, a whole land slipping sideways, mountains rolling over; dark ships fleeing into the dark. I want to tell someone about it, and get some kind of sense into it. Father would help: we could make up a good yarn together out of it. If I knew even the name of the place, it would turn a nightmare into a story.’

Darkness began to fall long before he got back. ‘I hope father will have had enough of himself and be chatty to-night,’ he thought. ‘The fireside is next best to a walk for discussing dreams.’ It was already night as he came up the path, and saw a light in the sitting-room.

He found his father sitting by the fire. The room seemed very still, and quiet – and too hot after a day in the open. Alboin sat, his head rested on one arm. His eyes were closed. He seemed asleep. He made no sign.

Audoin was creeping out of the room, heavy with disappointment. There was nothing for it but an early bed, and perhaps better luck tomorrow. As he reached the door, he thought he heard the chair creak, and then his father’s voice (far away and rather strange in tone) murmuring something: it sounded like herendil.

He was used to odd words and names slipping out in a murmur from his father. Sometimes his father would spin a long tale round them. He turned back hopefully.

‘Good night!’ said Alboin. ‘Sleep well, Herendil! We start when the summons comes.’ Then his head fell back against the chair.

‘Dreaming,’ thought Audoin. ‘Good night!’

And he went out, and stepped into sudden darkness.

Commentary on Chapters I and II

Alboin’s biography sketched in these chapters is in many respects closely modelled on my father’s own life – though Alboin was not an orphan, and my father was not a widower. Dates pencilled on the covering page of the manuscript reinforce the strongly biographical element: Alboin was born on February 4, (1891 >) 1890, two years earlier than my father. Audoin was born in September 1918.

‘Honour Mods.’ (i.e. ‘Honour Moderations’), referred to at the beginning of Chapter II, are the first of the two examinations taken in the Classical languages at Oxford, after two years (see Humphrey Carpenter, Biography, p. 62); ‘Schools’, in the same passage, is a name for the final Oxford examinations in all subjects.

Alboin’s father’s name Oswin is ‘significant’: ós ‘god’ and wine ‘friend’ (see IV. 208, 212); Elendil’s father was Valandil (p. 60). That Errol is to be associated in some way with Eriol (the Elves’ name for Ælfwine the mariner, IV. 206) must be allowed to be a possibility.*

The Lombardic legend

The Lombards (‘Long-beards’: Latin Langobardi, Old English Long-beardan) were a Germanic people renowned for their ferocity. From their ancient homes in Scandinavia they moved southwards, but very little is known of their history before the middle of the sixth century. At that time their king was Audoin, the form of his name in the Historia Langobardorum by the learned Paul the Deacon, who died about 790. Audoin and Old English Éadwine (later Edwin) show an exact correspondence, are historically the same name (Old English ēa derived from the original diphthong au). On the meaning of ēad see p. 46, and cf. Éadwine as a name in Old English of the Noldor, IV. 212.

Audoin’s son was Alboin, again corresponding exactly to Old English Ælfwine (Elwin). The story that Oswin Errol told his son (p. 37) is known from the work of Paul the Deacon. In the great battle between the Lombards and another Germanic people, the Gepids, Alboin son of Audoin slew Thurismod, son of the Gepid king Thurisind, in single combat; and when the Lombards returned home after their victory they asked Audoin to give his son the rank of a companion of his table, since it was by his valour that they had won the day. But this Audoin would not do, for, he said, ‘it is not the custom among us that the king’s son should sit down with his father before he has first received weapons from the king of some other people.’ When Alboin heard this he went with forty young men of the Lombards to king Thurisind to ask this honour from him. Thurisind welcomed him, invited him to the feast, and seated him at his right hand, where his dead son Thurismod used to sit.

But as the feast went on Thurisind began to think of his son’s death, and seeing Alboin his slayer in his very place his grief burst forth in words: ‘Very pleasant to me is the seat,’ he said, ‘but hard is it to look upon him who sits in it.’ Roused by these words the king’s second son Cunimund began to revile the Lombard guests; insults were uttered on both sides, and swords were grasped. But on the very brink Thurisind leapt up from the table, thrust himself between the Gepids and the Lombards, and threatened to punish the first man who began the fight. Thus he allayed the quarrel; and taking the arms of his dead son he gave them to Alboin, and sent him back in safety to his father’s kingdom.

It is agreed that behind this Latin prose tale of Paul the Deacon, as also behind his story of Alboin’s death, there lies a heroic lay: as early a vestige of such ancient Germanic poetry as we possess.

Audoin died some ten years after the battle, and Alboin became king of the Lombards in 565. A second battle was fought against the Gepids, in which Alboin slew their king Cunimund and took his daughter Rosamunda captive. At Easter 568 Alboin set out for the conquest of Italy; and in 572 he was murdered. In the story told by Paul the Deacon, at a banquet in Verona Alboin gave his queen Rosamunda wine to drink in a cup made from the skull of king Cunimund, and invited her to drink merrily with her father (‘and if this should seem to anyone impossible,’ wrote Paul, ‘I declare that I speak the truth in Christ: I have seen [Radgisl] the prince holding the very cup in his hand on a feastday and showing it to those who sat at the table with him.’)

Here Oswin Errol ended the story, and did not tell his son how Rosamunda exacted her revenge. The outcome of her machinations was that Alboin was murdered in his bed, and his body was buried ‘at the going up of the stairs which are near to the palace,’ amid great lamentation of the Lombards. His tomb was opened in the time of Paul the Deacon by Gislbert dux Veronensium, who took away Alboin’s sword and other gear that was buried with him; ‘wherefore he used to boast to the ignorant with his usual vanity that he has seen Alboin face to face.’

The fame of this formidable king was such that, in the words of Paul, ‘even down to our own day, among the Bavarians and the Saxons and other peoples of kindred speech, his open hand and renown, his success and courage in war, are celebrated in their songs.’ An extraordinary testimony to this is found in the ancient English poem Widsith, where occur the following lines:

Swylce ic wæs on Eatule mid Ælfwine:

se hæfde moncynnes mine gefræge

leohteste hond lofes to wyrcenne,

heortan unhneaweste hringa gedales,

beorhta beaga, beam Eadwines.

(I was in Italy with Alboin: of all men of whom I have heard he had the hand most ready for deeds of praise, the heart least niggard in the giving of rings, of shining armlets, the son of Audoin.)*

In my father’s letter of 1964 (given on pp. 7–8) he wrote as if it had been his intention to find one of the earlier incarnations of the father and son in the Lombard story: ‘It started with a father-son affinity between Edwin and Elwin of the present, and was supposed to go back into legendary time by way of an Eädwine and Ælfwine of circa A.D. 918, and Audoin and Alboin of Lombardic legend …’ But there is no suggestion that at the time this was any more than a passing thought; see further pp. 77–8.

The two Englishmen named Ælfwine (p. 38). King Alfred’s youngest son was named Æthelweard, and it is recorded by the twelfth century historian William of Malmesbury that Æthelweard’s sons Ælfwine and Æthelwine both fell at the battle of Brunanburh in 937.

Years later my father celebrated the Ælfwine who died at Maldon in The Homecoming of Beorhtnoth, where Torhthelm and Tídwald find his corpse among the slain: ‘And here’s Ælfwine: barely bearded, and his battle’s over.’

Oswin Errol’s reference to a ‘substratum’ (p. 40). Put very simply, the substratum theory attributes great importance, as an explanation of linguistic change, to the influence exerted on language when a people abandons their own former speech and adopts another; for such a people will retain their habitual modes of articulation and transfer them to the new language, thus creating a substratum underlying it. Different substrata acting upon a widespread language in different areas is therefore regarded as a fundamental cause of divergent phonetic change.

The Old English verses of Ælfwine Wídlást (p. 44). These verses, in identical form except for certain features of spelling, were used in the title-pages to the Quenta Silmarillion (p. 203); see also p. 103.

Names and words in the Elvish languages. Throughout, the term Eressëan was a replacement of Númenórean. Perhaps to be compared is FN II, §2: ‘Yet they [the Númenóreans] took on the speech of the Elves of the Blessed Realm, as it was and is in Eressëa.’ The term ‘Elf-latin’, applied by Alboin to ‘Eressëan’ (pp. 41, 43), is found in the Lhammas (p. 172). There it refers to the archaic speech of the First Kindred of the Elves (the Lindar), which ‘became early fixed … as a language of high speech and of writing, and as a common speech among all Elves; and all the folk of Valinor learned and knew this language.’ It was called Qenya, the Elvish tongue, tarquesta high-speech, and parmalambë the book-tongue. But it is not explained in The Lost Road why Alboin should have called the language that ‘came through’ to him by this term.

Amon-ereb (p. 38): the rough draft of this passage had Amon Gwareth, changed more than once and ending with Amon Thoros. Amon Ereb (the Lonely Hill) is found in the Annals of Beleriand (p. 143, annal 340) and in QS §113.

‘The shores of Beleriand’ (p. 38): the draft has here ‘the rocks of the Falassë.’ The form Falassë occurs on the Ambarkanta map IV (IV. 249).

‘Alda was a tree (a word I got a long time ago)’ (p. 41). Alda ‘tree’ is found in the very early ‘dictionary’ (I. 249), where also occurs the word lómë, which Alboin also refers to here, with the meanings ‘dusk, gloom, darkness’ (I. 255).

Anar, Isil, and Anor, Ithil (p. 41): in QS §75 the names of the Sun and Moon given by the Gods are Úrin and Isil, and by the Elves Anar and Rana (see the commentary on that passage).

The Eressëan fragment concerning the Downfall of Númenor and the Straight Road (p. 47) is slightly different in the draft text:

Ar Sauron lende nūmenorenna… lantie nu huine… ohtakárie valannar… manwe ilu terhante. eari lantier kilyanna nūmenor atalante… malle tēra lende nūmenna, ilya si maller raikar. Turkildi rómenna… nuruhuine me lumna.

And Sauron came to-Númenor… fell under Shadow… war-made on-Powers… ? ? broke. seas fell into-Chasm. Númenor down-fell. road straight went westward, all now roads bent. ? eastward. Death-shadow us is-heavy.

The name Tar-kalion is here not present, but Sauron is (see p. 9), and is interpreted as being a name. Most notably, this version has manwe (which Alboin could not interpret) for herunūmen ‘Lord-of-West’ of the later; on this see p. 75.

On the name Herendil (= Audoin, Eadwine) see Etymologies, stem KHER.

(ii)

The Númenórean chapters

My father said in his letter of 1964 on the subject that ‘in my tale we were to come at last to Amandil and Elendil leaders of the loyal party in Númenor, when it fell under the domination of Sauron.’ It is nonetheless plain that he did not reach this conception until after the extant narrative had been mostly written, or even brought to the point where it was abandoned. At the end of Chapter II the Númenórean story is obviously just about to begin, and the Númenórean chapters were originally numbered continuously with the opening ones. On the other hand the decision to postpone Númenor and make it the conclusion and climax to the book had already been taken when The Lost Road went to Allen and Unwin in November 1937.

Since the Númenórean episode was left unfinished, this is a convenient point to mention an interesting note that my father presumably wrote while it was in progress. This says that when the first ‘adventure’ (i.e. Númenor) is over ‘Alboin is still precisely in his chair and Audoin just shutting the door.’

With the postponement of Númenor the chapter-numbers were changed, but this has no importance and I therefore number these ‘III’ and ‘IV’; they have no titles. In this case I have found it most convenient to annotate the text by numbered notes.

Chapter III

Elendil was walking in his garden, but not to look upon its beauty in the evening light. He was troubled and his mind was turned inward. His house with its white tower and golden roof glowed behind him in the sunset, but his eyes were on the path before his feet. He was going down to the shore, to bathe in the blue pools of the cove beyond his garden’s end, as was his custom at this hour. And he looked also to find his son Herendil there. The time had come when he must speak to him.

He came at length to the great hedge of lavaralda1 that fenced the garden at its lower, western, end. It was a familiar sight, though the years could not dim its beauty. It was seven twelves of years2 or more since he had planted it himself when planning his garden before his marriage; and he had blessed his good fortune. For the seeds had come from Eressëa far westward, whence ships came seldom already in those days, and now they came no more. But the spirit of that blessed land and its fair people remained still in the trees that had grown from those seeds: their long green leaves were golden on the undersides, and as a breeze off the water stirred them they whispered with a sound of many soft voices, and glistened like sunbeams on rippling waves. The flowers were pale with a yellow flush, and laid thickly on the branches like a sunlit snow; and their odour filled all the lower garden, faint but clear. Mariners in the old days said that the scent of lavaralda could be felt on the air long ere the land of Eressëa could be seen, and that it brought a desire of rest and great content. He had seen the trees in flower day after day, for they rested from flowering only at rare intervals. But now, suddenly, as he passed, the scent struck him with a keen fragrance, at once known and utterly strange. He seemed for a moment never to have smelled it before: it pierced the troubles of his mind, bewildering, bringing no familiar content, but a new disquiet.

‘Eressëa, Eressëa!’ he said. ‘I wish I were there; and had not been fated to dwell in Númenor3 half-way between the worlds. And least of all in these days of perplexity!’

He passed under an arch of shining leaves, and walked swiftly down rock-hewn steps to the white beach. Elendil looked about him, but he could not see his son. A picture rose in his mind of Herendil’s white body, strong and beautiful upon the threshold of early manhood, cleaving the water, or lying on the sand glistening in the sun. But Herendil was not there, and the beach seemed oddly empty.

Elendil stood and surveyed the cove and its rocky walls once more; and as he looked, his eyes rose by chance to his own house among trees and flowers upon the slopes above the shore, white and golden, shining in the sunset. And he stopped and gazed: for suddenly the house stood there, as a thing at once real and visionary, as a thing in some other time and story, beautiful, beloved, but strange, awaking desire as if it were part of a mystery that was still hidden. He could not interpret the feeling.

He sighed. ‘I suppose it is the threat of war that maketh me look upon fair things with such disquiet,’ he thought. ‘The shadow of fear is between us and the sun, and all things look as if they were already lost. Yet they are strangely beautiful thus seen. I do not know. I wonder. A Númenórë! I hope the trees will blossom on your hills in years to come as they do now; and your towers will stand white in the Moon and yellow in the Sun. I wish it were not hope, but assurance – that assurance we used to have before the Shadow. But where is Herendil? I must see him and speak to him, more clearly than we have spoken yet. Ere it is too late. The time is getting short.’

‘Herendil!’ he called, and his voice echoed along the hollow shore above the soft sound of the light-falling waves. ‘Herendil!’

And even as he called, he seemed to hear his own voice, and to mark that it was strong and curiously melodious. ‘Herendil!’ he called again.

At length there was an answering call: a young voice very clear came from some distance away – like a bell out of a deep cave.

‘Man-ie, atto, man-ie?’

For a brief moment it seemed to Elendil that the words were strange. ‘Man-ie, atto? What is it, father?’ Then the feeling passed.

‘Where art thou?’

‘Here!’

‘I cannot see thee.’

‘I am upon the wall, looking down on thee.’

Elendil looked up; and then swiftly climbed another flight of stone steps at the northern end of the cove. He came out upon a flat space smoothed and levelled on the top of the projecting spur of rock. Here there was room to lie in the sun, or sit upon a wide stone seat with its back against the cliff, down the face of which there fell a cascade of trailing stems rich with garlands of blue and silver flowers. Flat upon the stone with his chin in his hands lay a youth. He was looking out to sea, and did not turn his head as his father came up and sat down on the seat.

‘Of what art thou dreaming, Herendil, that thy ears hear not?’

‘I am thinking; I am not dreaming. I am a child no longer.’

‘I know thou art not,’ said Elendil; ‘and for that reason I wished to find thee and speak with thee. Thou art so often out and away, and so seldom at home these days.’

He looked down on the white body before him. It was dear to him, and beautiful. Herendil was naked, for he had been diving from the high point, being a daring diver and proud of his skill. It seemed suddenly to Elendil that the lad had grown over night, almost out of knowledge.

‘How thou dost grow!’ he said. ‘Thou hast the makings of a mighty man, and have nearly finished the making.’

‘Why dost thou mock me?’ said the boy. ‘Thou knowest I am dark, and smaller than most others of my year. And that is a trouble to me. I stand barely to the shoulder of Almáriel, whose hair is of shining gold, and she is a maiden, and of my own age. We hold that we are of the blood of kings, but I tell thee thy friends’ sons make a jest of me and call me Terendul4 – slender and dark; and they say I have Eressëan blood, or that I am half-Noldo. And that is not said with love in these days. It is but a step from being called half a Gnome to being called Godfearing; and that is dangerous.’5

Elendil sighed. ‘Then it must have become perilous to be the son of him that is named elendil; for that leads to Valandil, God-friend, who was thy father’s father.’6

There was a silence. At length Herendil spoke again: ‘Of whom dost thou say that our king, Tarkalion, is descended?’

‘From Eärendel the mariner, son of Tuor the mighty who was lost in these seas.’7

‘Why then may not the king do as Eärendel from whom he is come? They say that he should follow him, and complete his work.’

‘What dost thou think that they mean? Whither should he go, and fulfil what work?’

‘Thou knowest. Did not Eärendel voyage to the uttermost West, and set foot in that land that is forbidden to us? He doth not die, or so songs say.’

‘What callest thou Death? He did not return. He forsook all whom he loved, ere he stepped on that shore.8 He saved his kindred by losing them.’

‘Were the Gods wroth with him?’

‘Who knoweth? For he came not back. But he did not dare that deed to serve Melko, but to defeat him; to free men from Melko, not from the Lords; to win us the earth, not the land of the Lords. And the Lords heard his prayer and arose against Melko. And the earth is ours.’

‘They say now that the tale was altered by the Eressëans, who are slaves of the Lords: that in truth Eärendel was an adventurer, and showed us the way, and that the Lords took him captive for that reason; and his work is perforce unfinished. Therefore the son of Eärendel, our king, should complete it. They wish to do what has been long left undone.’

‘What is that?’

‘Thou knowest: to set foot in the far West, and not withdraw it. To conquer new realms for our race, and ease the pressure of this peopled island, where every road is trodden hard, and every tree and grass-blade counted. To be free, and masters of the world. To escape the shadow of sameness, and of ending. We would make our king Lord of the West: Nuaran Númenóren.9 Death comes here slow and seldom; yet it cometh. The land is only a cage gilded to look like Paradise.’

‘Yea, so I have heard others say,’ said Elendil. ‘But what knowest thou of Paradise? Behold, our wandering words have come unguided to the point of my purpose. But I am grieved to find thy mood is of this sort, though I feared it might be so. Thou art my only son, and my dearest child, and I would have us at one in all our choices. But choose we must, thou as well as I – for at thy last birthday thou became subject to arms and the king’s service. We must choose between Sauron and the Lords (or One Higher). Thou knowest, I suppose, that all hearts in Númenor are not drawn to Sauron?’

‘Yes. There are fools even in Númenor,’ said Herendil, in a lowered voice. ‘But why speak of such things in this open place? Do you wish to bring evil on me?’

‘I bring no evil,’ said Elendil. ‘That is thrust upon us: the choice between evils: the first fruits of war. But look, Herendil! Our house is one of wisdom and guarded learning; and was long revered for it. I followed my father, as I was able. Dost thou follow me? What dost thou know of the history of the world or Númenor? Thou art but four twelves,10 and wert but a small child when Sauron came. Thou dost not understand what days were like before then. Thou canst not choose in ignorance.’

‘But others of greater age and knowledge than mine – or thine – have chosen,’ said Herendil. ‘And they say that history confirmeth them, and that Sauron hath thrown a new light on history. Sauron knoweth history, all history.’

‘Sauron knoweth, verily; but he twisteth knowledge. Sauron is a liar!’ Growing anger caused Elendil to raise his voice as he spoke. The words rang out as a challenge.

‘Thou art mad,’ said his son, turning at last upon his side and facing Elendil, with dread and fear in his eyes. ‘Do not say such things to me! They might, they might…’

‘Who are they, and what might they do?’ said Elendil, but a chill fear passed from his son’s eyes to his own heart.

‘Do not ask! And do not speak – so loud!’ Herendil turned away, and lay prone with his face buried in his hands. ‘Thou knowest it is dangerous – to us all. Whatever he be, Sauron is mighty, and hath ears. I fear the dungeons. And I love thee, I love thee. Atarinya tye-meláne.’

Atarinya tye-meláne, my father, I love thee: the words sounded strange, but sweet: they smote Elendil’s heart. ‘A yonya inye tye-méla: and I too, my son, I love thee,’ he said, feeling each syllable strange but vivid as he spoke it. ‘But let us go within! It is too late to bathe. The sun is all but gone. It is bright there westwards in the gardens of the Gods. But twilight and the dark are coming here, and the dark is no longer wholesome in this land. Let us go home. I must tell and ask thee much this evening – behind closed doors, where maybe thou wilt feel safer.’ He looked towards the sea, which he loved, longing to bathe his body in it, as though to wash away weariness and care. But night was coming.

The sun had dipped, and was fast sinking in the sea. There was fire upon far waves, but it faded almost as it was kindled. A chill wind came suddenly out of the West ruffling the yellow water off shore. Up over the fire-lit rim dark clouds reared; they stretched out great wings, south and north, and seemed to threaten the land.

Elendil shivered. ‘Behold, the eagles of the Lord of the West are coming with threat to Númenor,’ he murmured.

‘What dost thou say?’ said Herendil. ‘Is it not decreed that the king of Númenor shall be called Lord of the West?’

‘It is decreed by the king; but that does not make it so,’ answered Elendil. ‘But I meant not to speak aloud my heart’s foreboding. Let us go!’

The light was fading swiftly as they passed up the paths of the garden amid flowers pale and luminous in the twilight. The trees were shedding sweet night-scents. A lómelindë began its thrilling bird-song by a pool.

Above them rose the house. Its white walls gleamed as if moonlight was imprisoned in their substance; but there was no moon yet, only a cool light, diffused and shadowless. Through the clear sky like fragile glass small stars stabbed their white flames. A voice from a high window came falling down like silver into the pool of twilight where they walked. Elendil knew the voice: it was the voice of Fíriel, a maiden of his household, daughter of Orontor. His heart sank, for Fíriel was dwelling in his house because Orontor had departed. Men said he was on a long voyage. Others said that he had fled the displeasure of the king. Elendil knew that he was on a mission from which he might never return, or return too late.11 And he loved Orontor, and Fíriel was fair.

Now her voice sang an even-song in the Eressëan tongue, but made by men, long ago. The nightingale ceased. Elendil stood still to listen; and the words came to him, far off and strange, as some melody in archaic speech sung sadly in a forgotten twilight in the beginning of man’s journey in the world.

Ilu Ilúvatar en káre eldain a fírimoin

ar antaróta mannar Valion: númessier.....

The Father made the World for elves and mortals, and he gave it into the hands of the Lords, who are in the West.

So sang Fíriel on high, until her voice fell sadly to the question with which that song ends: man táre antáva nin Ilúvatar, Ilúvatar, enyáre tar i tyel íre Anarinya qeluva? What will Ilúvatar, O Ilúvatar, give me in that day beyond the end, when my Sun faileth?’12

‘E man antaváro? What will he give indeed?’ said Elendil; and stood in sombre thought.

‘She should not sing that song out of a window,’ said Herendil, breaking the silence. ‘They sing it otherwise now. Melko cometh back, they say, and the king shall give us the Sun forever.’

‘I know what they say,’ said Elendil. ‘Do not say it to thy father, nor in his house.’ He passed in at a dark door, and Herendil, shrugging his shoulders, followed him.

Chapter IV

Herendil lay on the floor, stretched at his father’s feet upon a carpet woven in a design of golden birds and twining plants with blue flowers. His head was propped upon his hands. His father sat upon his carved chair, his hands laid motionless upon either arm of it, his eyes looking into the fire that burned bright upon the hearth. It was not cold, but the fire that was named ‘the heart of the house’ (hon-maren)13 burned ever in that room. It was moreover a protection against the night, which already men had begun to fear.

But cool air came in through the window, sweet and flower-scented. Through it could be seen, beyond the dark spires of still trees, the western ocean, silver under the Moon, that was now swiftly following the Sun to the gardens of the Gods. In the night-silence Elendil’s words fell softly. As he spoke he listened, as if to another that told a tale long forgotten.14

‘There15 is Ilúvatar, the One; and there are the Powers, of whom the eldest in the thought of Ilúvatar was Alkar the Radiant;16 and there are the Firstborn of Earth, the Eldar, who perish not while the World lasts; and there are also the Afterborn, mortal Men, who are the children of Ilúvatar, and yet under the rule of the Lords. Ilúvatar designed the World, and revealed his design to the Powers; and of these some he set to be Valar, Lords of the World and governors of the things that are therein. But Alkar, who had journeyed alone in the Void before the World, seeking to be free, desired the World to be a kingdom unto himself. Therefore he descended into it like a falling fire; and he made war upon the Lords, his brethren. But they established their mansions in the West, in Valinor, and shut him out; and they gave battle to him in the North, and they bound him, and the World had peace and grew exceeding fair.

‘After a great age it came to pass that Alkar sued for pardon; and he made submission unto Manwë, lord of the Powers, and was set free. But he plotted against his brethren, and he deceived the Firstborn that dwelt in Valinor, so that many rebelled and were exiled from the Blessed Realm. And Alkar destroyed the lights of Valinor and fled into the night; and he became a spirit dark and terrible, and was called Morgoth, and he established his dominion in Middle-earth. But the Valar made the Moon for the Firstborn and the Sun for Men to confound the Darkness of the Enemy. And in that time at the rising of the Sun the Afterborn, who are Men, came forth in the East of the world; but they fell under the shadow of the Enemy. In those days the exiles of the Firstborn made war upon Morgoth; and three houses of the Fathers of Men were joined unto the Firstborn: the house of Bëor, and the house of Haleth, and the house of Hador. For these houses were not subject to Morgoth. But Morgoth had the victory, and brought all to ruin.

‘Eärendel was son of Tuor, son of Huor, son of Gumlin, son of Hador; and his mother was of the Firstborn, daughter of Turgon, last king of the Exiles. He set forth upon the Great Sea, and he came at last unto the realm of the Lords, and the mountains of the West. And he renounced there all whom he loved, his wife and his child, and all his kindred, whether of the Firstborn or of Men; and he stripped himself.17 And he surrendered himself unto Manwë, Lord of the West; and he made submission and supplication to him. And he was taken and came never again among Men. But the Lords had pity, and they sent forth their power, and war was renewed in the North, and the earth was broken; but Morgoth was overthrown. And the Lords put him forth into the Void without.

‘And they recalled the Exiles of the Firstborn and pardoned them; and such as returned dwell since in bliss in Eressëa, the Lonely Isle, which is Avallon, for it is within sight of Valinor and the light of the Blessed Realm. And for the men of the Three Houses they made Vinya, the New Land, west of Middle-earth in the midst of the Great Sea, and named it Andor, the Land of Gift; and they endowed the land and all that lived thereon with good beyond other lands of mortals. But in Middle-earth dwelt lesser men, who knew not the Lords nor the Firstborn save by rumour; and among them were some who had served Morgoth of old, and were accursed. And there were evil things also upon earth, made by Morgoth in the days of his dominion, demons and dragons and mockeries of the creatures of Ilúvatar.18 And there too lay hid many of his servants, spirits of evil, whom his will governed still though his presence was not among them. And of these Sauron was the chief, and his power grew. Wherefore the lot of men in Middle-earth was evil, for the Firstborn that remained among them faded or departed into the West, and their kindred, the men of Númenor, were afar and came only to their coasts in ships that crossed the Great Sea. But Sauron learned of the ships of Andor, and he feared them, lest free men should become lords of Middle-earth and deliver their kindred; and moved by the will of Morgoth he plotted to destroy Andor, and ruin (if he might) Avallon and Valinor.19

‘But why should we be deceived, and become the tools of his will? It was not he, but Manwë the fair, Lord of the West, that endowed us with our riches. Our wisdom cometh from the Lords, and from the Firstborn that see them face to face; and we have grown to be higher and greater than others of our race – those who served Morgoth of old. We have knowledge, power, and life stronger than they. We are not yet fallen. Wherefore the dominion of the world is ours, or shall be, from Eressëa to the East. More can no mortals have.’

‘Save to escape from Death,’ said Herendil, lifting his face to his father’s. ‘And from sameness. They say that Valinor, where the Lords dwell, has no further bounds.’

‘They say not truly. For all things in the world have an end, since the world itself is bounded, that it may not be Void. But Death is not decreed by the Lords: it is the gift of the One, and a gift which in the wearing of time even the Lords of the West shall envy.20 So the wise of old have said. And though we can perhaps no longer understand that word, at least we have wisdom enough to know that we cannot escape, unless to a worse fate.’

‘But the decree that we of Númenor shall not set foot upon the shores of the Immortal, or walk in their land – that is only a decree of Manwë and his brethren. Why should we not? The air there giveth enduring life, they say.’

‘Maybe it doth,’ said Elendil; ‘and maybe it is but the air which those need who already have enduring life. To us perhaps it is death, or madness.’

‘But why should we not essay it? The Eressëans go thither, and yet our mariners in the old days used to sojourn in Eressëa without hurt.’

‘The Eressëans are not as we. They have not the gift of death. But what doth it profit to debate the governance of the world? All certainty is lost. Is it not sung that the earth was made for us, but we cannot unmake it, and if we like it not we may remember that we shall leave it. Do not the Firstborn call us the Guests? See what this spirit of unquiet has already wrought. Here when I was young there was no evil of mind. Death came late and without other pain than weariness. From Eressëans we obtained so many things of beauty that our land became well nigh as fair as theirs; and maybe fairer to mortal hearts. It is said that of old the Lords themselves would walk at times in the gardens that we named for them. There we set their images, fashioned by Eressëans who had beheld them, as the pictures of friends beloved.

‘There were no temples in this land. But on the Mountain we spoke to the One, who hath no image. It was a holy place, untouched by mortal art. Then Sauron came. We had long heard rumour of him from seamen returned from the East. The tales differed: some said he was a king greater than the king of Númenor; some said that he was one of the Powers, or their offspring set to govern Middle-earth. A few reported that he was an evil spirit, perchance Morgoth returned; but at these we laughed.21

‘It seems that rumour came also to him of us. It is not many years – three twelves and eight22 – but it seems many, since he came hither. Thou wert a small child, and knew not then what was happening in the east of this land, far from our western house. Tarkalion the king was moved by rumours of Sauron, and sent forth a mission to discover what truth was in the mariners’ tales. Many counsellors dissuaded him. My father told me, and he was one of them, that those who were wisest and had most knowledge of the West had messages from the Lords warning them to beware. For the Lords said that Sauron would work evil; but he could not come hither unless he were summoned.23 Tarkalion was grown proud, and brooked no power in Middle-earth greater than his own. Therefore the ships were sent, and Sauron was summoned to do homage.

‘Guards were set at the haven of Moriondë in the east of the land,24 where the rocks are dark, watching at the king’s command without ceasing for the ships’ return. It was night, but there was a bright Moon. They descried ships far off, and they seemed to be sailing west at a speed greater than the storm, though there was little wind. Suddenly the sea became unquiet; it rose until it became like a mountain, and it rolled upon the land. The ships were lifted up, and cast far inland, and lay in the fields. Upon that ship which was cast highest and stood dry upon a hill there was a man, or one in man’s shape, but greater than any even of the race of Númenor in stature.

‘He stood upon the rock25 and said: “This is done as a sign of power. For I am Sauron the mighty, servant of the Strong” (wherein he spoke darkly). “I have come. Be glad, men of Númenor, for I will take thy king to be my king, and the world shall be given into his hand.”

‘And it seemed to men that Sauron was great; though they feared the light of his eyes. To many he appeared fair, to others terrible; but to some evil. But they led him to the king, and he was humble before Tarkalion.

‘And behold what hath happened since, step by step. At first he revealed only secrets of craft, and taught the making of many things powerful and wonderful; and they seemed good. Our ships go now without the wind, and many are made of metal that sheareth hidden rocks, and they sink not in calm or storm; but they are no longer fair to look upon. Our towers grow ever stronger and climb ever higher, but beauty they leave behind upon earth. We who have no foes are embattled with impregnable fortresses – and mostly on the West. Our arms are multiplied as if for an agelong war, and men are ceasing to give love or care to the making of other things for use or delight. But our shields are impenetrable, our swords cannot be withstood, our darts are like thunder and pass over leagues unerring. Where are our enemies? We have begun to slay one another. For Númenor now seems narrow, that was so large. Men covet, therefore, the lands that other families have long possessed. They fret as men in chains.

‘Wherefore Sauron hath preached deliverance; he has bidden our king to stretch forth his hand to Empire. Yesterday it was over the East. To-morrow – it will be over the West.

‘We had no temples. But now the Mountain is despoiled. Its trees are felled, and it stands naked; and upon its summit there is a Temple. It is of marble, and of gold, and of glass and steel, and is wonderful, but terrible. No man prayeth there. It waiteth. For long Sauron did not name his master by the name that from old is accursed here. He spoke at first of the Strong One, of the Eldest Power, of the Master. But now he speaketh openly of Alkar,26 of Morgoth. He hath prophesied his return. The Temple is to be his house. Númenor is to be the seat of the world’s dominion. Meanwhile Sauron dwelleth there. He surveys our land from the Mountain, and is risen above the king, even proud Tarkalion, of the line chosen by the Lords, the seed of Eärendel.

‘Yet Morgoth cometh not. But his shadow hath come; it lieth upon the hearts and minds of men. It is between them and the Sun, and all that is beneath it.’

‘Is there a shadow?’ said Herendil. ‘I have not seen it. But I have heard others speak of it; and they say it is the shadow of Death. But Sauron did not bring that; he promiseth that he will save us from it.’

‘There is a shadow, but it is the shadow of the fear of Death, and the shadow of greed. But there is also a shadow of darker evil. We no longer see our king. His displeasure falleth on men, and they go out; they are in the evening, and in the morning they are not. The open is insecure; walls are dangerous. Even by the heart of the house spies may sit. And there are prisons, and chambers underground. There are torments; and there are evil rites. The woods at night, that once were fair – men would roam and sleep there for delight, when thou wert a babe – are filled now with horror. Even our gardens are not wholly clean, after the sun has fallen. And now even by day smoke riseth from the temple: flowers and grass are withered where it falleth. The old songs are forgotten or altered; twisted into other meanings.’

‘Yea: that one learneth day by day,’ said Herendil. ‘But some of the new songs are strong and heartening. Yet now I hear that some counsel us to abandon the old tongue. They say we should leave Eressëan, and revive the ancestral speech of Men. Sauron teacheth it. In this at least I think he doth not well.’