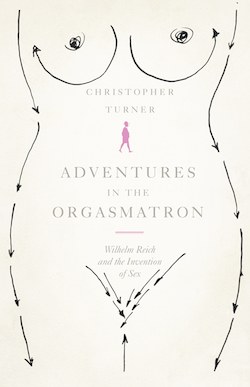

Читать книгу Adventures in the Orgasmatron: Wilhelm Reich and the Invention of Sex - Christopher Turner - Страница 10

ОглавлениеChapter Two

By 1922 the Austrian economy, which had been in free fall since 1919, teetered on the brink of collapse. The country was still devastated by its wartime expenditures, and the rate of inflation was out of control. Immediately after the war there had been twelve billion Austrian crowns in circulation; by the end of 1922 this figure had reached four trillion.1 While the country’s industry lay idle, lacking the coal and oil needed to power factories, the government’s printing presses ran at full speed, working day and night to produce new banknotes. Knapsacks replaced wallets as people carried around bundles of virtually worthless paper. In 1922 a 500,000-crown note was issued, a denomination no one would have believed possible a year earlier. Despite its incessant printing, the central bank couldn’t keep up with the hyperinflation, and provincial towns had to produce their own emergency money.

Visitors flocked to Austria to exploit the favorable rate of exchange. Stefan Zweig wrote of Austria’s “calamitous ‘tourist season,’ ” during which the nation was plundered by greedy foreigners: “Whatever was not nailed down, disappeared.”2 Even England’s unemployed turned up to take advantage, finding that they could live in luxury hotels in Austria on the government benefits with which they could hardly survive in slums back home. None of the indigenous population wanted Austrian crowns, which most merchants no longer accepted, and there was a scramble to swap them for secure foreign currency, or any goods available. Freud hired a language tutor to brush up on his shaky English so that he could take Americans into analysis, who paid him in U.S. dollars.

In October 1922 the Christian Social chancellor, Ignaz Seipel, secured a large loan of 26 million pounds sterling from the League of Nations to stabilize the depleted economy. The budget was balanced the following year under draconian foreign supervision by the league’s permanent members, who insisted that Austria unburden itself of a bloated bureaucracy. That year Vienna, which unlike the rest of the country had a clear Social Democratic majority, was declared a separate province from the otherwise predominantly rural province of Lower Austria. This gave the Social Democrats the power to raise their own taxes and implement an ambitious reform program without the need for their radical policies to be ratified by an unsympathetic assembly in Lower Austria. Excluded from national power, and exploiting the new period of prosperity, the Social Democrats concentrated on turning Vienna into a Socialist mecca, a model Western alternative to the Bolshevik experiment.

In 1923 the new city-state instituted a housing construction tax (the burden of which was on businesses and the diminishing middle class); 2,256 new residential units were built by the end of the year to redress the desperate housing shortage and to help clear the slums. Over the next decade, four hundred large communal housing blocks were built, planned around spacious courtyards, some of which spanned several city blocks. These increased the housing stock by 11 percent and housed 200,000 people, who were charged only token rents. The new “people’s apartment palaces,” as they were referred to, contained libraries, community centers, clinics, laundries, gyms, swimming pools, cinemas, and cooperative stores. The pride of these super-blocks, called the Karl-Marx-Hof, was built by a student of the architect Otto Wagner. Another was named after Freud.

These bastions were described by their Christian Social critics as “red fortresses,” suspected of being strategically sited and designed to be easily defendable in case of civil war. Vienna was hemmed in by the surrounding provinces from which it was now separated politically, and planners were therefore unable to enlarge the capital with garden city satellites. The historian Helmut Gruber describes the new housing blocks as reflecting the status of Vienna itself, a Social Democratic island in a national sea of Christian Socials: “Enclosed, isolated and defensive,” he writes, “they were enclaves within an enclave.”3

However, the Social Democratic politicians hoped that their form of “anticipatory socialism” would be infectious and serve as a springboard back to government. In 1923 their share of the national vote stood at 39 percent, but in Vienna they could count on a two-thirds majority in municipal elections. In Vienna, after the disillusionment of the immediate postwar years, the Social Democrats had managed to restore confidence in the revolutionary idea that modernism— reflected in the functional, streamlined forms of the architecture they sponsored— could reshape people’s lives for the better. The Social Democratic politician Otto Bauer claimed proudly that his party was “creating a revolution of souls.”4

As the Christian Socials grumbled about “tax sadism,” Vienna, like Weimar Berlin, became a model of social welfare, with not only excellent public housing but also enviable public health services. As city welfare councillor for Vienna, Julius Tandler, Reich’s former anatomy teacher, was responsible for the health and well-being of every citizen. The Social Democrats extended to everyone “cradle-to-grave” care. Tandler was also in charge of early childhood education and initiated kindergartens and child welfare centers, and arranged for the building of numerous swimming pools and gyms. Under his tenure mortality rates dropped to 25 percent of prewar levels and, thanks to a government-sponsored proliferation of maternity clinics, the rate of child mortality halved.

Though it was not state-funded, the free psychoanalytic clinic, the Ambulatorium, that opened at Pelikangasse 18 in May 1922, offering free therapy for all, regardless of their capacity to pay, should be seen in the context of Tandler’s and the Social Democrats’ politics of benevolent paternalism. In September 1918, Sigmund Freud had given a speech at the Fifth International Congress of Psychoanalysis in Budapest. It was two months before the Armistice (Reich had just reached Vienna on leave), and almost all the forty-two analysts who attended appeared in military uniform, having been conscripted as army doctors to treat war neuroses, their success at which had won psychoanalysis begrudging respect from conventional psychiatry. But Freud looked to the future rather than dwelling on civilization’s obvious discontents, promising his audience, “The conscience of society will awake and remind it that the poorest man should have just as much right to assistance for his mind as he now has to life-saving help offered by surgery.”5 To this end, and sounding more like a health reformer than a psychoanalyst, Freud urged his followers to create “institutions or out-patient clinics . . . where treatment shall be free.” Keen to contribute to a better postwar world, Freud hoped that one day these charitable clinics would be state-funded. “The neuroses,” he insisted, “threaten public health no less than tuberculosis.”6

The psychoanalyst Max Eitingon, who came from a wealthy family of Galician fur traders and had funded the first of these clinics, established in Berlin in 1920, later wrote that Freud had spoken “half as prophecy and half as challenge.”7 Eitingon had directed the psychiatric divisions of several Hungarian military hospitals during the war. He set up the Berlin Poliklinik with Ernst Simmel, who had been director of a Prussian hospital for shell-shocked soldiers. The Poliklinik, which reflected a postwar spirit of practicality, might be seen as the psychoanalysts’ attempt to adapt the intensive treatment of war neuroses to shattered civilian life.

The Berlin Poliklinik was a chic but modest outpost for this military-style campaign against nervous disease; it occupied the fourth floor of an unassuming block and it had only five rooms. Freud’s son Ernst, an architect who had trained with Adolf Loos, designed the Spartan, minimalist interior. There was a large lecture hall–cum–waiting room with dark wooden floors, a blackboard, and forty chairs; four consulting rooms led off it through soundproofed double doors, and were tastefully furnished with heavy drapes, portraits of Freud, and simple cane couches. One patient was struck by the apparent lack of medical paraphernalia and walked out disappointed, muttering, “No ultraviolet lamps?”

We don’t tend to think of Freud as a militant social worker, and imagine he was more likely to be found excavating the minds of the idle and twitchy rich. The psychoanalyst Karl Abraham, who was to become director of the Berlin Poliklinik, complained of just such a clientele in a letter to Freud written before the outbreak of World War One: “My experience is that at the moment there is only one kind of patient who seeks treatment— unmarried men with inherited money.”8 But Abraham’s six Poliklinik staff were soon swamped with patients from all social backgrounds: they performed twenty analytic sessions on opening day. Though it was supposedly free, most patients did in fact make a modest contribution, evaluated on a sliding scale according to their means. Factory workers, office clerks, academics, artisans, domestic servants, a bandleader, an architect, and a general’s daughter were expected to pay, Eitingon explained, only “as much or as little as they can or think they can for treatment.” Freud praised Eitingon for initiating the drive to make psychoanalysis accessible to “the great multitude who are too poor themselves to repay an analyst for his laborious work.”9

The Berlin Poliklinik was always intended to be a flagship institution, and following its rapid success— 350 people applied for treatment in its first year— a second free clinic was founded two years later in Freud’s native city (between the wars at least a dozen more were opened in seven countries and ten cities, from Paris to Moscow). According to Ernest Jones, who set up a clinic in West London in 1926, Freud was initially “lukewarm” about the idea of having a free clinic in Vienna, because he felt that only he could head it. However, the Berlin Poliklinik seemed to have turned its city into the new capital of psychoanalysis— Fenichel emigrated there in 1922, attracted by its vibrant reputation— and the Viennese analysts didn’t want to be upstaged. Paul Federn (then Reich’s analyst), Helene and Felix Deutsch, and Eduard Hitschmann pressed the idea upon Freud.

In May 1922 Hitschmann, a specialist in female frigidity (Reich had given Hitschmann’s book on the subject to Lia Laszky), was appointed the first director of Vienna’s Ambulatorium. Helene Deutsch later described Hitschmann, a resolute Social Democrat who had been practicing analysis since 1905, as “a cultured, witty man . . . 200 percent ‘normal.’ ”10 Reich became Hitschmann’s first clinical assistant and would remain at the Ambulatorium for the rest of the decade. In 1924, he became the clinic’s deputy medical director with the job of interviewing and examining all prospective patients, sending off the ones he suspected of having a physical rather than a psychosomatic illness for X-rays and blood tests, and assigning the rest to an analyst. Each member of the Vienna Psychoanalytic Society promised to treat at least one patient for free to support the clinic, which represented a fifth of their practice. If they couldn’t spare the time, Reich would collect the equivalent in monthly dues.

The Ambulatorium had been two years in the planning not only because of Freud’s initial intransigence but because the psychiatrist Julius Wagner-Jauregg, a member of the conservative Christian Social Party and the head of the Society of Physicians, had blocked the proposals to launch a free clinic connected to the Garrisons-Spital (military hospital). Wagner-Jauregg, the director of the University Clinic for Psychiatry and Nervous Diseases, was then Vienna’s most celebrated doctor and one of Freud’s most notorious and sarcastic critics— “His whole personality,” his onetime assistant Helene Deutsch wrote in describing his resistance to psychoanalysis, “was too deeply committed to the rational, conscious aspects of life.”11 With the support of other psychiatrists who were not well-disposed toward psychoanalysis, Wagner-Jauregg, who took an entire year to examine Hitschmann’s proposal for the free clinic before he rejected it, argued that the clinic was an unnecessary supplement to existing ones like his own and constituted a breach of trade.

Reich would no doubt have been aware of Wagner-Jauregg’s efforts to block the Ambulatorium when he began a two-year stint of postgraduate work in neuropsychiatry with Wagner-Jauregg and Paul Schilder, the doctor to whom Reich had referred Lore Kahn’s mother. When Reich studied under him, Wagner-Jauregg was experimenting with electrotherapy and insulin shock treatments, and with inducing malaria to cure the dementia associated with the final stages of syphilis. It was found that the resulting fever could kill all pathogenic bacteria; the innovation would win him the Nobel Prize in 1927.

Wagner-Jauregg had been a friend of Freud’s when they were students. He once carried him to bed after Freud blacked out from drink, and he was one of the few to use the familiar du to address him. However, the pair fell out in 1920 when Freud testified against Wagner-Jauregg before a parliamentary commission. Wagner-Jauregg had been accused of excessive use of force in treating the military “malingerers,” as he called those he felt were feigning illness as a form of desertion. At the beginning of the war he had treated war neurotics with isolation and a milk diet, but he soon found that a strong dose of electric shock therapy was the best method of getting “simulators” to return to active duty, a feat he claimed to have achieved after as little as one session of torture. Freud accused him of having used psychiatry like a machine gun to force sick soldiers back to the front. In his autobiography, Wagner-Jauregg wrote that he considered Freud’s public statement a “personal attack.”12

Reich received his first exposure to schizophrenic patients when he worked as an intern for a year on the “chronic ward” at the Steinhof State Lunatic Asylum in Vienna. There Wagner-Jauregg used bromides and barbiturates to sedate patients, which, Reich noticed critically, had no effect on their underlying psychotic symptoms. He wrote sympathetically of the inmates, “Each and every one of them experienced the inner collapse of his world and, in order to keep afloat, had constructed a new delusional world in which he could exist.”13 His own analyst, Paul Federn, claimed some success in penetrating and curing schizophrenic fantasies using psychoanalysis. Reich liked Wagner-Jauregg’s “rough peasant candour” and admired his impressive diagnostic skill, but working with him created split loyalties.14 Reich had already decided to give over his career to psychoanalysis, but to avoid being a target of his professor’s derisive wit, at Wagner-Jauregg’s clinic he made sure to exclude all mention of sexual symbolism from his patients’ case histories.

The Ambulatorium, which eventually opened at the General Hospital (where Felix Deutsch was a physician) just after Freud turned sixty-six, couldn’t have been more different from its sleek, modernist cousin in Berlin. Its shabby clapboard building was a carbuncle on the Beaux Arts architecture that surrounded it. The building was shared with the Society of Heart Specialists, whose physicians vacated it in the afternoons. The psychoanalysts used the emergency entrance for heart-attack victims as a meeting room, and the unit’s four ambulance garages made makeshift consulting rooms. A metal examination table with an uncomfortable springboard mattress doubled as a couch (patients had to use a stepladder to get onto it), and the analyst perched on a hard wooden stool. “After five sessions we felt the effects of so long a contact with the hard surface,” recalled the psychoanalyst Richard Sterba.15 He had occupied both the stool and the table, having been analyzed at the Ambulatorium for free by Hitschmann and later, with Reich’s help, having gotten his first job at the clinic.

There was nothing elitist about psychoanalysis as Reich practiced it at the Ambulatorium. According to a report published by Hitschmann in 1932, 22 percent of the clinic’s patients were either housewives or unemployed, and another 20 percent were laborers. In its first decade, 1,445 men and 800 women were treated in the Ambulatorium’s improvised space, more than the 1,955 people treated at the Berlin Poliklinik. “The consultation hours were jammed,” Reich recalled, “There were industrial workers, office clerks, students, and farmers from the country. The influx was so great that we were at a loss to deal with it.”16

These figures are especially impressive, considering the skeleton staff with which the institution operated, and show how accepted psychoanalysis was increasingly becoming among the general public. But they also show how far psychoanalysis was from providing what Eitingon ambitiously called “therapy for the masses.”17 Eitingon himself regretted that the clinics couldn’t reach more “authentic proletarian elements.” Yet it was specifically the ambition of the second-generation analysts to do this—to universalize psychoanalysis with the aim of treating the social causes of neurosis rather than merely patching up the mental health of individual sufferers—that led to ruptures that almost destroyed the profession.

Freud, in launching the radical social project that was the free clinics, inspired the “revolutionism” of the second generation of analysts, as one of their members, Helene Deutsch, termed it (echoing Otto Bauer’s idea of a “revolution of souls”). They were, she said, “drawn to everything that is newly formed, newly won, newly achieved.”18 These now legendary figures, who staffed the free clinics in Berlin and Vienna and came to believe that psychoanalysis could play a utopian role in liberating man from social and sexual repression, included Deutsch herself (who had been a lover of the socialist leader Herman Lieberman), Wilhelm and Annie Reich, Otto Fenichel, Edith Jacobson, Karen Horney, and Erich Fromm.

The year Reich joined the Ambulatorium staff, Fenichel instituted what became known as the children’s seminar for young psychoanalysts in Berlin, so called not because it was devoted to child analysis but because Fenichel liked to think of the rebellious analysts as “naughty children.”19 In Vienna there was a similar generational gap, and a corresponding rebellion of values. It is notable that in a photograph of the Ambulatorium’s volunteers taken in the mid-1920s, there were only two gray-haired members: Ludwig Jekels and Hitschmann, who were both about thirty years older than Reich. For the young recruits, even more than for their superiors, psychoanalysis was, as the historian Elizabeth Danto puts it, “a challenge to conventional political codes, a social mission more than a medical discipline.”20

Swamped with patients at the Ambulatorium, Reich felt he was “ ‘swimming’ in matters of technique,” at sea in trying to apply psychoanalytic theory to an inundated practice.21 He knew that he was supposed to break down the barrier of unconscious resistance with which the patient repressed any childhood sexual conflict so that the emotion-laden memory could break through and evaporate into consciousness, and he knew how to work with the transference so that it became a curative force in therapy. But what was one to do with uncooperative or catatonic analysands who refused to play the game of free association or did not want to have dreams? How to communicate with patients to whom the language of psychoanalysis was entirely foreign? When Reich told his uneducated patients, as he was supposed to, that they had a resistance or that they were defending themselves against their unconscious, they just responded with vacant stares.

There was no training institute or organized curriculum where Reich could discuss these practical problems. When he expressed his concerns to more experienced analysts, he said, “the older colleagues never tired of repeating, ‘Just keep on analyzing!’ . . . ‘you’ll get there.’ ” Where one was supposed to “get,” Reich added, no one seemed to know.22 Reich would take particularly puzzling cases to Freud, to whom he seems to have had privileged access. One of the cases about which he sought advice was that of his first analysand, the impotent waiter Freud had referred to Reich who was still not cured three years later.

Reich had managed to trace the origin of the man’s problem to his having witnessed, at the age of two, the bloody scene of his mother’s giving birth to a second child. This had left his patient, Reich noted, with severe castration anxiety, “a feeling of ‘emptiness’ in his own genitals.”23 However, though he had theoretically solved the case by unearthing the unconscious root of his problem, an epiphany to which the patient displayed no obvious signs of resistance, the waiter remained uncured.24

Freud warned against too much “therapeutic ambitiousness” and advised Reich to be patient and not force things; he also suggested, “Just go ahead. Interpret.”25 However, Reich declared a stalemate and dismissed the patient a few months later. His first case was a defeat that would plague him. Freud told his disciples only what not to do in therapy, preferring to leave what one should do, as he told Ferenczi, to “tact.” Freud later admitted that his more “docile” followers did not perceive the elasticity of his rules and obeyed them as if they were rigid taboos. According to Reich, Freud deemed only a handful of analysts to have truly mastered his technique. At the Seventh International Psychoanalytic Congress, in Berlin in 1922, where Freud gave a lecture that was the germ of the following year’s paper “The Ego and the Id,” he looked out at all the people in attendance and whispered conspiratorially to Reich, “See that crowd? How many do you think can analyse, can really analyse?”26 Freud held up only five fingers, even though there were 112 analysts present.

Many psychoanalysts thought of themselves as passive screens for their patients’ unconscious projections and hardly intervened in their free associations. If their analysands were silent, they advocated matching these silences; they joked among themselves that they had to smoke a lot to keep awake during such unproductive sessions. (One analyst who had awoken to find an empty couch justified his having dozed off by claiming that his unconscious was able to dutifully watch over his patient even as he slept.) Reich experimented with this passive technique, but it did not suit his energetic character— he had been attracted to analysis by Freud, who was, as Reich saw it, a dynamic conquistador of the psyche. When Reich put up a blank façade, as some advised, he found that his patients “only developed a profound helplessness, a bad conscience, and thus became stubborn.”27

Soon after he joined the staff at the Ambulatorium, Reich suggested to Freud the establishment of a technical seminar to explore alternative techniques. When the idea received Freud’s blessing, the first-ever teaching program for psychoanalysts was launched. The technical seminar, initially led by Reich’s superiors, Eduard Hitschmann and Hermann Nunberg (Reich took over in 1924), was aimed at less experienced analysts, but senior analysts regularly joined the debate. It took place in the Society of Heart Specialists’ windowless basement; the “long room with a long table and big heavy chairs,” according to Helen Ross, a trainee who had made the pilgrimage to Vienna from Chicago, was made even more claustrophobic by the fact that it was clouded in cigar smoke.28 The seminar propelled Reich to the center of the theoretical debates then taking place within the profession. In this concentrated, heavy atmosphere, the analysts presented the stories of their therapeutic struggles (Reich offered his foundering case of the impotent waiter) and thrashed out possible solutions in the hope of forging a new, clinically grounded psychoanalytic technique.

When Freud had introduced the idea of free clinics, in Budapest in 1918, he had also spoken optimistically about “a new field of analytic technique” that was “still in the course of being evolved.”29 In the early 1920s there were two main areas of innovation to which Freud might have been referring: Ernest Jones and Karl Abraham were pioneering “character theory,” and Otto Rank and the Hungarian analyst Sándor Ferenczi (who made sure to attend the technical seminar when he was in Vienna) were pursuing what they called “active therapy.” Reich would ultimately try to fuse these two strands, but the former played a greater role in the birth of his theory of the function of the orgasm.

Freud supposed that a child went through a series of developmental stages during which the infantile libido was concentrated on the mouth (the oral stage), then the anus (the anal stage), and the genitals (the phallic stage)— these phases were normally surmounted in weaning, toilet training, and the developing of the Oedipus complex; only after making these rites of passage could a person accede, finally, to full, adult genitality (the genital stage). Freud thought that neurotics had stalled at one of these earlier stages, where their libidos were prematurely dammed up and spilled over not only into symptoms and perversions but also into negative character traits. In his 1908 essay on the anal character, for example, Freud observed that many of his patients who were unconsciously fixated on the anal stage displayed traits such as orderliness, parsimoniousness, and obstinacy.

Ernest Jones and Karl Abraham built on Freud’s observations to elaborate on a further series of personality traits for the oral, anal, phallic, and genital types. It was hoped that the analyst, armed with a list of character types, would immediately be able to recognize and understand defective developments, and therefore correct them more quickly.30 Reich’s first book, The Impulsive Character: A Psychoanalytic Study of Ego Pathology (1925), based on his treatment of patients at the Ambulatorium with especially troubled backgrounds, represented his attempt to contribute to this trend toward characterology; in the book he argued for a “single, systematic theory of character . . . a psychic embryology.”31

Because Freud saw psychosexual development as a linear progression culminating in full genitality, it was inevitable that the genital character was destined to display virtues lacking in the other stages. As the historian of psychoanalysis Nathan G. Hale has observed, the genital character was held up by many analysts as the “norm of human attainment.” The individual who had conquered all other stages to achieve the primacy of the genital phase was able to blend the most useful features of these earlier stages in a harmony of traits; from the oral stage, Abraham wrote of this ideal type, the genital character had retained “ forward-pushing energy; from the anal stage, endurance and perseverance; from sadistic sources [which Freud traced to both the oral and anal phases] the necessary power to carry on the struggle for existence.”32

Reich, like most analysts, came to assert that establishing genital primacy was the only goal of therapy, but he equated this achievement with orgasm (of which his ex-patient, the impotent waiter, remained deprived). He asserted that genital disturbance was the most important symptom of neurosis. “It is quite striking,” Reich wrote in his essay “On Genitality” (1924), that “amongst the twenty-eight male and fourteen female neurotics I have treated, there was not one who did not manifest symptoms of impotence, frigidity, or sexual abstinence. A survey of several other analysts revealed similar findings.”33 Reich thought a wave of genital excitement in orgasm would rupture the stagnant dams of repression he saw in these patients and shortcut the long, slow process of analysis by leading them more quickly to full genitality.

Reich would encourage, indeed teach, his patients to have regular orgasms. When he instructed one of his patients, an elderly woman suffering from a nervous tic that interfered with her breathing, how to masturbate, Reich wrote that her symptom suddenly subsided. He worked with another young man to dissolve the guilt he felt over masturbation, the cause, Reich thought, of his patient’s headaches, nausea, back pains, and absentmindedness. These symptoms apparently cleared up when he discovered complete gratification in the act. (“Guidance of masturbational practices during treatment,” Reich concluded in a 1922 study of several of the eccentric sexual habits of the Ambulatorium’s patients, is “an essential and active therapeutic tool in the hands of the analyst.”)34

Reich persuaded one woman who was in a sexless marriage to have an affair with a young suitor; he seemed to encourage, or at least condone, others’ sleeping with prostitutes. Reich came increasingly to believe that enabling the patient to achieve orgasm was the measure of successful therapy. The process of analysis had troubled Reich because it had no clearly defined goal, and now he felt he’d found the means to the end of resolving neurosis in the orgasm.

Though there was considerable resistance to this theory from other analysts, Reich’s ideas would later position him at the fore-front of the group of younger psychoanalysts. As the second generation of therapists sought to redefine the relationship between the erotic demands of an increasingly liberated youth and the repressive moral pressures that constrained them, Reich’s theory of the orgasm became the defining metaphor for their sexual revolt.

Inducing orgasm to treat hysteria was an ancient cure that went back to the classical Greeks, who thought that an orgasm might reposition the wandering womb from which hysteria took its name. As the historian Rachel Maines has shown in The Technology of Orgasm, “massage to orgasm of female patients was a staple of medical practice among some (but certainly not all) Western physicians from the time of Hippocrates until the 1920s.”35 The treatment, aimed at relieving congestion of the womb, was not without its moral risks; one turn-of-the-century doctor claimed that the task “should be entrusted to those who have ‘clean hands and a pure heart.’ ”36

In 1878 an electro-mechanical vibrator was used at Paris’s Salpêtrière Hospital to treat female hysterics, which introduced a further degree of clinical distance. That year a male doctor at the institution, Desiré Magloire Bourneville, published a three-volume photographic atlas depicting patients suffering from hysteria and epilepsy that contained photos of women in the throes of mechanically stimulated orgasms. One eighteen-year-old patient referred to as “Th.” in Bourneville’s notes is reported to have cried “Oue! Oue!” as she approached climax, before throwing back her head and rocking her torso violently: “Then her body curves into an arc and holds this position for several seconds,” Bourneville wrote. “One then observes some slight movements of the pelvis . . . she raises herself, lies flat again, utters cries of pleasure, laughs, makes several lubricious movements and sinks down on to the vulva and right hip.”37 During her ecstasy Bourneville made detailed physiological notes from his vantage point as the machine’s operator: “La vulve est humide . . . La secretion vaginale est très abondante.”38 From the 1880s, the vibrator became a widely used tool, an essential piece of equipment in many doctors’ offices and sanatoriums, which gave speed and efficiency to a previously manual process. By the 1920s the device began to appear in the first pornographic films, which discredited it somewhat as a purely medical tool.

Freud would have been aware of Bourneville’s innovations when he interned at the Salpêtrière in 1885, as well as the other vibrating helmets and shaking chairs Charcot used to calm his hysterical patients. At one evening reception he attended at the hospital, Freud heard Charcot excitedly telling a colleague that hysteria always had a genital origin (“C’est toujours la chose génitale, toujours! Toujours! Toujours!”), explaining that all neuroses could be traced back to the “marriage bed” (as in the particular case under discussion, which involved an impotent husband).39 Freud wrote that he was “almost paralyzed with astonishment” at the time, the idea was so shocking, and he soon repressed Charcot’s never-published observation.40

When Freud returned to Vienna and established his private practice, he was reminded of Charcot’s controversial remark when his colleague Rudolf Chrobak referred a hysterical patient to him who was still a virgin despite having been married for eighteen years. Chrobak commented sarcastically, “We know only too well what the only prescription is for such cases, but we can’t prescribe it. It is: ‘Penis normalis. Dosim repetatur!’ ”41 At his clinic Freud employed hydrotherapy, electrotherapy, massage, and the Weir-Mitchell rest cure before abandoning these methods in favor of hypnosis. Rachel Maines wonders whether Freud, who claimed a certain expertise when he distinguished the vaginal from the clitoral orgasm (he considered the latter immature and inferior, to the annoyance of many 1960s feminists), ever operated as a “gynaecological masseur.” In Studies on Hysteria Freud wrote of the case of “Elisabeth von R.,” who had an orgasm when he “pressed or pinched” her legs, supposedly to test her response to pain.42

In a letter dated 1893 to his friend and mentor Wilhelm Fliess, Freud noted that nervous illness was frequently a consequence of an abnormal sex life and speculated about a possible cure for neuroses along free-love lines: “The only alternative would be free sexual intercourse between young men and women. Otherwise the alternatives are masturbation, neurasthenia . . . In the absence of such a solution society seems doomed to fall victim to incurable neuroses.”43 In his first decade of practicing psychoanalysis, Freud continued to maintain that neuroses were caused by enforced abstinence and coitus interruptus (a belief his diaphragm-fitting colleague, Isidor Sadger, evidently still held in the early twenties), which forced the libido to find alternative outlets in hysterical and neurotic behavior. In 1905, even after his relationship with Fliess had disintegrated, Freud continued to maintain that “in a normal vita sexualis no neurosis is possible.”44

Some of Freud’s colleagues, one of them the Austrian doctor Otto Gross, took these ideas to extremes, encouraging people to throw off what he considered to be the out-of-date moral prejudices that caused sickness: “Repress nothing!”45 Freud held Gross in high esteem, and thought he had the most original mind among his followers (according to Ernest Jones, who befriended Gross and considered their conversations to have constituted his first analysis, Gross was “the nearest approach to a romantic genius I ever met”), though Gross’s morphine and cocaine addiction made him a paranoid and a particularly wild analyst.46 In September 1907, Jung wrote to Freud of Gross’s radical ideas: “Dr. Gross tells me that he puts a quick stop to the transference by turning people into sexual immoralists. He says the transference to the analyst and its persistent fixation are mere monogamy symbols and as such symptomatic of repression. The truly healthy state for the neurotic is sexual immor ality.”47 (Jung would treat Gross in Switzerland the following year for his drug addiction.)

In his paper “ ‘Civilized Sexual Morality and Modern Nervousness,’ ” published in 1908, Freud criticized the puritanical sexual mores that so often lead to neurosis and sadism, such as enforced monogamy and abstinence. Freud implied that a lack of sex was as degenerative to the species as inbreeding, and that further repressions of the sexual instincts might endanger the very existence of the human race. “I have not gained the impression,” Freud wrote, “that sexual abstinence helps to shape energetic, self-reliant men of action, nor original thinkers, bold pioneers and reformers; far more often it produces ‘good’ weaklings who later become lost in the crowd.”48 Freud posed the question: Is civilized sexual morality worth the sacrifice it imposes upon us? It was this fundamental question that Reich took up.

Reich thought he noticed the same sex-deprived weakness in his patients and, like Gross, celebrated sexual immorality as a cure. Reich followed Freud in believing that a core of dammed-up sexual energy acted as a reservoir for neuroses to sprout up. Adopting Freud’s hydraulic notion of the libido, he came to believe that a healthy sex life, full of orgasms— at least one a day if possible— would deprive these symptoms of the sustenance that they needed to grow by maintaining a healthy flow of sexual energy. (The writer Arthur Schnitzler, a caddish bachelor, former doctor, and a friend of Freud’s, kept a diary in which he recorded his orgasms, sometimes as many as eight a night, and drew up monthly totals subdivided by each mistress; he omitted tallying theirs.)

However, by the time Reich first visited him at Berggasse 19, Freud was moving away from such a sexually radical solution to mental health problems. In 1920, the year after Reich met him, Freud published Beyond the Pleasure Principle, which set Thanatos against Eros, the death drive against the sex drive, and marked a decisive shift away from his early thinking about repression. In that essay he argued that the drive for gratification, love, and life is always overshadowed by a self-destructive urge toward aggression and death.

Freud’s theory of anxiety evolved in parallel with this shift in his thinking. In his Introductory Lectures on Psychoanalysis (1917), Freud regarded anxiety, like hysteria, as an outgrowth of sexual repression, caused by unsatisfied libido, which— like wine turning to vinegar— seeks discharge in palpitations and breathlessness, dizziness and nausea. However, Freud now asserted that anxiety was a cause rather than an effect of repression: “It was not the repression that created the anxiety,” Freud wrote in Inhibitions, Symptoms and Anxiety (1926). “The anxiety was there earlier; it was the anxiety that made the repression.”49 Freud now suggested that repression wasn’t something that could be thrown off, as Reich would maintain, but was an intrinsic part of the human condition. To Freud, misery came from within; to Reich, it was imposed from without.

Reich claimed to have kept his discovery of the therapeutic powers of the orgasm to himself at first, because he thought that the world of psychoanalysis wasn’t yet ready for his theory: “The actual goal of therapy,” he recalled, “that of making the patient capable of orgasm, was not mentioned in the first years of the seminar. I avoided the subject instinctively.”50 In fact, Reich did air his theory quite early, at a meeting of the Vienna Psychoanalytic Society in November 1923, where it met with a frosty reception:

During my presentation, I became aware of a growing chilliness in the mood of the meeting. I was a good speaker and had always been listened to attentively. When I finished, an icy stillness hung over the room. Following a break, the discussion began. My contention that the genital disturbance was an important, perhaps the most important symptom of the neurosis was said to be erroneous . . . Two analysts literally asserted that they knew any number of female patients who had a “completely healthy sex life.” They appeared to me to be more excited than was in keeping with their usual scientific reserve.51

The only member of the older generation to support him on that occasion (and only privately) was his boss at the Ambulatorium, Eduard Hitschmann, who told him afterward, “You hit the nail on the head!”52 Reich had evolved his ideas under Hitschmann’s supervision. Hitschmann, the expert in curing frigidity and impotence, was famous for treating sexual disturbances with a calm practicality; when the analyst Fritz Perls, who later went back into analysis with Reich to be treated for impotence, lay on Hitschmann’s couch and told him of the anxieties he had about his manhood, Hitschmann said, “Well, take out your penis. Let’s have a look at the thing.”53 According to the Minutes of the Vienna Psychoanalytic Society, Hitschmann “always advocated searching for ‘organic factors’ as a background of the neurosis,” which is just what Reich thought he’d discovered in the orgasm.54

Encouraged by Hitschmann, and desperate to prove the universality of his theory, Reich began to collect case histories that same month, grilling patients at the Ambulatorium about the minutiae of their sex lives. In 1924 he was promoted to assistant director, and could incorporate in his study information from the weekly written summaries his colleagues were required to submit to him (patients were assigned case numbers to protect their privacy); statistics were collected on 410 individuals, 72 of them Reich’s own patients.

At the congress in Salzburg later that year, Reich, armed with this data, insisted that there was now no doubt that “the severity of neurotic disturbance is directly proportionate to the psychogenital disturbance.”55 Reich maintained that the majority of the people who came to the Ambulatorium had some form of genital problem. The incidence of impotence at the clinic, where it was reported to be the most common condition, might have been so high, the historian Elizabeth Danto has suggested, because impotence was one of the most prevalent effects of shell shock. But it might equally be understood in terms of Reich’s own diagnostic agenda: according to Hitschmann’s report on the clinic, cases of impotence slumped in 1930, when Reich left for Berlin. Furthermore, Reich claimed that the problem afflicted not just patients. He estimated that 80 to 90 percent of all women and about 70 to 80 percent of all men were sexually sick, victims of libidinal stasis.56 He warned that, as well as neurosis, such genital stagnation could bring about “heart ailments . . . excessive perspiration, hot flashes and chills, trembling, dizziness, diarrhea, and, occasionally, increased salivation.”57

In reply to the critics, who claimed to have plenty of neurotic but sexually active patients in treatment, Reich made a distinction between sexual activity and sexual satisfaction; the neurotic patients who seemed to be exceptions to his rule weren’t enjoying “total orgasms,” he said. These, Reich argued, went beyond mere ejaculation, which even a neurotic might occasionally manage; they completely absorbed the participants in tender and all-consuming pleasure. In Thalassa, the influential theory of genitality that Ferenczi published in 1924, Ferenczi wrote that there was a satisfying “genitofugal” backflow of libido on orgasm, from the genitals to the rest of the body, which gave “that ineffable feeling of bliss.”58 In idealizing non-neurotic sex, Reich similarly united tenderness and sensuousness in an almost sacred act, as he emphasized when summarizing his theory: “It is not just to fuck, you understand, not the embrace in itself, not the intercourse. It is the real emotional experience of the loss of your ego, of your whole spiritual self.”59

Each sexually ill or disturbed patient Reich saw failed to live up to this increasingly refined standard of “orgastic potency.” In his paper “The Therapeutic Significance of Genital Libido” (1924), Reich laid down eight rules for the “total orgasm”:

The forepleasure acts may not be disproportionately prolonged; libido released in extensive forepleasure weakens the orgasm.

Tiredness, limpness, and a strong desire to sleep following intercourse are essential.

Orgastically potent women often feel a need to cry out during the climax.

In the orgastically potent, a slight clouding of consciousness regularly occurs in intercourse if it is not engaged in too frequently. [He doesn’t qualify what an overdose might be.]

Disgust, aversion, or decrease of tender impulses toward the partner following intercourse imply an absence of orgastic potency and indicate that effective counterimpulses and inhibiting ideas were present during coition. Whoever coined the expression “Post coitum omnia animalia tristia sunt” [After intercourse, all animals are sad] must have been orgastically impotent.

Male lack of consideration for the woman’s satisfaction indicates a lack of tender attachment. [“Don Juan types are attempting to compensate for an inordinate fear of impotence,” he wrote elsewhere.]

The fear of some women during coition that the male member will become limp too early and that they will not be able to “finish” also makes the presence of orgastic potency questionable, or at least indicates severe instability. Usually active castration desire is at the root of this fear, and the penis becoming flaccid after ejaculation is interpreted as castration. This reaction may also be caused by the fear of losing the penis, which the woman fantasizes as her own.

It is also important to discover the coital position assumed, especially that of the woman. Incapability of rhythmic responsive movements inhibits the orgasm; likewise, maximal stretching of lower pelvic muscles in women from wide spreading of the legs is indispensable for intense orgastic sensations.60

Reich, as already mentioned, would give his neurotic patients advice on technique so that they could achieve the ideal orgasm, as if he were a sex educator rather than a psychoanalyst. He would even visit his patients’ homes, asking to see the person’s spouse to enlighten him or her as to the partner’s needs. “No analysis may be considered complete,” Reich wrote, “as long as genital orgastic potency is not guaranteed.”61

Reich asked several of his patients to draw graphs, illustrating their different experiences of orgasm before and after he cured them, intended to illustrate the seismic difference in levels of satisfaction. Theodoor H. Van de Velde’s popular 1926 sex guide, Ideal Marriage: Its Physiology and Technique (there were forty-two German reprintings by 1933), contained similar graphs depicting the comparative trajectories of women’s and men’s sexual excitement as they approached mutual orgasm. Some of these coital timelines were included in Reich’s The Function of the Orgasm (1927), the first full-length book on the topic. (Despite his busy schedule, Reich was very disciplined about his writing, to which he devoted a few hours every day except Sunday.) For Reich, as these diagrams show, a potent orgasm built up slowly through friction in foreplay into a tsunami-like wave, to peak in a huge crest that dropped off with a shudder and an explosion.

Until he conducted his survey, Reich’s theory lacked any empirical foundation and he was accused of operating solely on autobiographical evidence. Indeed, Reich told Richard Sterba that if he didn’t have an orgasm for two days, “he felt physically unwell and ‘saw black before his eyes’ as before an approaching spell of fainting. These symptoms disappeared immediately with an orgasmic experience.”62 Sterba described Reich as a “genital narcissist.” Indeed, when Reich writes of the “genital character” he might be describing the way he’d like to be perceived: “[He] can be very gay but also intensely angry. He reacts to an object-loss with depression but does not get lost in it; he is capable of intense love but also of intense hatred; he can be . . . childlike but he will never appear infantile; his seriousness is natural and not stiff in a compensatory way because he has no tendency to show himself grown-up at all costs.”63 Reich believed that other analysts were resistant to his theory because of unconscious sexual jealousy; they weren’t as “potent” as he.

In his diary Reich provides two early glimpses of his own orgastic potency: his momentous night with a prostitute as a fifteen-year-old boy (“I was all penis!”), and an apparently earth-shattering experience he had at nineteen with the young Italian woman he lived with in Gemona del Friuli, the village to the north of Venice where he stayed as a reservist during the last stages of the war. In an unpublished memoir of his sex life, a copy of which is in the National Library of Medicine in Washington, again written in the third person, Reich described how, while sleeping with this woman, “he and she felt completely One, not only in the genital but all over; there was not the least experiential distinction between the two organisms; they were ONE organism, as if united or melted into each other . . . When the orgasm finally mounted and overtook them, they burst into sweet crying, both of them, in a calm, but intense manner, and they sank deeper and deeper into each other.”64

On April 27 , 1924, Annie Reich gave birth to the couple’s first child, a daughter they named Eva. They moved into a large double apartment in an opulent stucco building on Lindenstrasse, which looked out onto a women’s prison. It was sumptuously furnished, thanks to the wealth of the bourgeois family Reich had married into. They employed a nursemaid, who enforced a strict feeding schedule, and kept careful Freudian records of Eva’s development through the early oral and anal stages of her life.

Reich was enjoying what he would later call his “dancing and discussing Goethe stage”— he and Annie had active professional and social lives.65 They went to the Austrian Alps for frequent winter skiing trips, a sport at which Reich excelled, and visited the Austrian lakes with their friends in the summer; they went to parties in Vienna, and on picnics and hikes. When Reich joined the psychoanalysts, they were an isolated group of dissenters; but now Freud was fast gaining acceptance, and Reich and his friends— almost all analysts— were enjoying their new status as a more reputable part of the avant-garde. That year, to celebrate Freud’s sixty-eighth birthday, Vienna’s City Council gave Freud the Bürgerrecht, an honor akin to the freedom of the city.

Reich was now at the forefront of the psychoanalytic movement, the acknowledged leader of its second generation, just as Freud was withdrawing from that scene. In October 1923, Freud’s upper palate was excised because of the cancer that riddled his jaw, an affliction for which he underwent thirty more operations in his final sixteen years. After his malignant tumor was cut out, Freud had to wear a prosthesis, known as “the monster” by his family, to shut off his mouth from his nasal cavity so that he was able to eat and talk. Freud stubbornly continued to smoke; to get a cigar between his teeth, he now had to hold open his jaw with the help of a clothes peg. “The monster” had to be adjusted every few days, to stop it from grating against his cancer-raw inner cheek, and a related infection would soon make him deaf in one ear— his right, luckily, which made it unnecessary for him to turn around the analytic couch at whose head he sat.

The analysts Karl Abraham and Felix Deutsch both visited Freud in a villa he’d rented in Semmering, a village in the Austrian Alps, as he recuperated from this first of many operations. “We spoke a lot about Professor [Freud],” Deutsch wrote afterward, “how he withdraws more and more from people, which A[braham] had occasion to experience for himself when he was staying at Semmering. Up in his workroom Professor [Freud] has a telescope with which he studies the moon and the stars, and by day he studies the hills and the mountains of the region. He withdraws more and more from the world.”66

Paul Federn, Reich’s former analyst, the vice president of the Vienna Psychoanalytic Society, had increased power as acting chairman in Freud’s absence. Like Sadger, he had lost all enthusiasm for his protégé Reich in the course of analyzing him. Federn had decided that Reich was “aggressive, paranoid and ambitious,” all traits he found distasteful.67 One of Reich’s biographers, Myron Sharaf, suggests that Federn especially disapproved of the frequent extramarital affairs Reich spoke about in his analysis. Futhermore, Federn— whom Reich later described mockingly as “a prophet, with a beard”— did not share Reich’s celebration of the orgasm. In 1927, the year The Function of the Orgasm appeared, Federn published a book (with Heinrich Meng) in which it was claimed that “abstinence is not injurious to health”; cold baths, holding one’s breath, and swimming were prescribed to temper the sex drive.68

Federn would start “digging” against him, as Reich put it, by trying to convince Freud that Reich’s behavior was belligerent to the point of being pathological, and he encouraged Freud to take action in response to the increasing complaints from colleagues about Reich’s orgasm fanaticism. “His collaboration was for a time welcoming and stimulating,” Helene Deutsch recalled of the shifting mood concerning Reich. “He worked at the Ambulatorium and his clinical reports were usually very informative for his younger colleagues. After a time he himself devalued the quality of his work by trying to make certain ideas, correct in themselves, but obvious and not entirely original, into the central concept of psychoanalysis. His aggressive way of advancing these ideas was typical of him . . . His presumptuous and aggressive, I might even say paranoid, personality was hard to bear.”69

Federn was in charge of who was invited to attend the monthly meetings held in Freud’s drawing room at Berggasse 19, which took place on the second Friday of every month. Freud, working on his autobiography, was seriously ill and preoccupied with the specter of death; he attended only one further general meeting and never went to another psychoanalytic congress, so these private meetings were the only chance many of his devotees had of seeing him. Freud had decided that only twelve disciples could come at one time— there were six places for the permanent members of the society’s executive committee and six to be rotated among the remaining members.

In 1924 Reich put himself forward for the role of second secretary of the Vienna Psychoanalytic Society, a junior position that would have guaranteed him one of the much-desired regular spots at these monthly meetings. He was elected, but without Reich’s knowledge, Federn persuaded Freud to overrule the ballot in favor of Robert Jokl, Reich’s older colleague at the Ambulatorium. Freud regretted his unethical decision when he read and was impressed by the proofs of Reich’s The Impulsive Character, which was published the following year and in which Reich made no explicit reference to his theory of the orgasm. In treating the “drifters, liars, and contentious complainers,” who like psychotic patients seemed to have no control over their impulses, Reich had bravely put himself on the front line of the profession.70 Reich was attracted to these characters because they didn’t exhibit the sexual repression that he thought so pernicious— seemingly free of a superego, impulsive characters acted on every whim thrown up by their unconscious. They were the clinical equivalent of Peer Gynt.

Reich found that all the patients he deemed impulsive characters had been sexually active from a very young age, but that their youthful curiosity about sex had been suddenly repressed by a guilt-inducing trauma. Reich’s American disciple Elsworth Baker would later refer to Reich himself as an “impulsive character” and, knowing the circumstances of his mother’s death, would presume Reich identified with the troubled childhoods of these difficult patients.

One of the patients Reich wrote about in his book was a twenty-six-year-old masochist and nymphomaniac who could feel pleasure only when she masturbated with a knife, deliberately cutting herself in the process until she caused a prolapse of her uterus. This woman’s mother had thrown a knife at her when she had caught her masturbating as a young girl, which, he thought, explained her method of self-mutilation. The nymphomaniac’s bullying older brother, with whom she’d had sex when she was ten, was now in prison serving a sentence for rape. She had married but was having an affair with a sadist who whipped her, and when Reich forbade her from continuing that relationship— threatening to end the analysis if she didn’t— she brought a whip to her sessions and began to strip, demanding that her analyst lash her instead. Reich had to physically stop her from undressing. She then took to following him as he walked the streets of Vienna. She came to his door at ten o’clock one night, wanting him to have sex with her or whip her. She said that she desired a child by him and, Reich discovered, she attempted to poison her husband and older sister with rat poison to clear the way— only Reich could satisfy her, she said. When he told her that would be impossible, she went to a shop and bought a revolver with the intention of murdering him.

Reich managed to break through his patient’s initial mistrust and ambivalence toward him (she wanted both to have sex with him and to kill him), and her refusal to recognize that she might be ill, to cultivate a positive transference. The patient would frequently declare that she didn’t want to end their sessions, manipulating Reich into a position where he had to be strict and threaten to have her removed by force; she’d leave screaming, her masochism satisfied, crying that nobody loved her. Over fourteen months of treatment, Reich succeeded in assuaging her anxieties and in stopping her practice of self-harm, and she was able to start a job.

Freud, who limited his practice to neurotics, was impressed with Reich’s handling of such dangerous cases, which extended psychoanalysis into the treatment of the early stages of schizophrenia. On December 14 , 1924, Freud backed down on his decision to oust Reich from his rightful post, writing to Federn that Reich should be judged by his work, not his character:

Shortly after you left I read a manuscript by Dr. Reich which he sent me this morning. I found it so full of valuable content that I very much regretted that we had renounced the recognition of his endeavors. In this mood it occurred to me that for us to propose Dr. Jokl as second secretary is improper because we had no right to change arbitrarily a decision made by the Committee. In the light of this fact, what you told me about private animosities against Dr. Reich is not significant.71

When Federn protested, saying that he’d already told Jokl of his appointment, Freud refused to save him the embarrassment of having to put the situation right. Reich never was given the appointment, though at this stage Reich did not seem to be aware of the snub. It is not clear how Federn managed to finally persuade Freud to oust Reich; Reich later came to believe that Federn told Freud that Reich slept with his patients.

At the end of 1924, Reich’s brother, Robert, contracted tuberculosis, the disease that had killed his father, and he returned to Vienna from Romania, where he was in charge of arranging shipping on the Danube for his transportation company. He had married Ottilie Heifetz three years earlier and now had a young daughter of his own, Sigrid. Reich met his brother at the station and used his medical connections to ensure that Robert saw the best doctors in the city. Robert was advised to go to a sanatorium in Italy to recover; Reich sent morphine and other expensive medicine and, in anticipation of his later theories, advice on breathing techniques to help his brother aerate his consumption-spotted lungs. But, to Robert’s disappointment, Reich never visited him there— he claimed he was too busy, no doubt embroiled in the battles within the Vienna Psychoanalytic Society.

Robert died in April 1926, and his widow and daughter lived with the Reichs for a year in Vienna, where Reich helped Ottilie start a new career as a nursery teacher. In a curious twist, Ottilie married Annie Pink’s father after his wife died, thereby becoming Reich’s new mother-in-law.

In January 1925, the Training Institute, a teaching arm of the Vienna Psychoanalytic Society, was set up in order to instruct psychoanalysts to-be. Freud wanted this entity to be able to accept lay practitioners, which the Ambulatorium wasn’t able to do, as it had received a license on condition that only M.D.’s would practice there.

Located about half an hour’s walk from the Ambulatorium, in the Wollzeile, the Training Institute of the Vienna Psychoanalytic Society was run by Helene Deutsch, who was thirteen years Reich’s senior. She had been the only female psychiatrist at Julius Wagner-Jauregg’s clinic during the war (she lost her job when Paul Schilder returned from the battlefield), and had just spent a year at the training institute in Berlin, where she studied under its director, Karl Abraham.

Deutsch told her biographer, Paul Roazen, that the Training Institute was designed in part to alienate Reich, and that measures were taken to submit Reich’s “obstinate insistence upon his ideas [“the false propaganda of the ‘orgiastic’ ideology”] . . . to an objective control.”72 Despite having been denied a place on the executive committee, Reich had assumed the position of leader of the technical seminar, and he was also promoted to deputy medical director of the Ambulatorium, roles he occupied until he joined Feni chel in Berlin in 1930, despite Federn’s continued attempts to persuade Freud to replace him. Federn and Freud worried that Reich would use the technical seminar to indoctrinate trainees with his orgasm theory, and the Training Institute was a way to disperse his power. Its four-term curriculum subsumed many of the technical seminar’s educational tasks, and even though he was granted a seat on the institute’s training committee, Reich’s monopoly on teaching effectively ended.

Though at that time many analysts in Vienna didn’t share Reich’s views on sex—or considered them “obvious,” as Deutsch did—he was thought to be a brilliant analyst of certain types of patient. Even Federn claimed that Reich was the best diagnostician among the younger generation, and his technical seminar at the Ambulatorium was so instructive that many of the older members of the society attended it regularly. Reich conducted the seminar “with informality and spontaneity,” recalled his American pupil Walter Briehl.73 Reich made sure that each session was devoted to discussing a therapeutic failure (Reich, it must be remembered, never completed his own analysis), and the discussions of these cases sometimes went on until one in the morning. “Reich had an unusual gift of empathy with his patients,” Richard Sterba wrote of Reich’s precise and clear diagnoses. “He was an impressive personality full of youthful intensity. His manner of speaking was forceful; he expressed himself well and decisively. He had an unusual flair for psychic dynamics. His clinical astuteness and technical skill made him an excellent teacher.”74 Anna Freud attended Reich’s technical seminar and once sent Reich an admiring postcard saying that he was a spiritus rector, an “inspiring teacher.”75

The year that Reich took over the technical seminar, Freud’s disciples Sándor Ferenczi and Otto Rank, both of whom Freud considered potential heirs after Jung had fallen out of favor, published The Development of Psychoanalysis (1924). They criticized “classical technique” for its arid devotion to theory rather than therapy, and proposed a new method to speed up and refine the talking cure and to break through the most stagnant cases; they pointed out that in the early days of analysis it was not unusual for cures to be achieved in a matter of days or weeks. Ferenczi and Rank suggested an “active technique of interference,” in which the psychoanalyst would set a definite time limit to therapy and act less as an emotionally detached surgeon of the psyche, listening from his unseen position behind the couch and offering cool interpretations, and more as an assertive guide who would goad and challenge the patient. Ferenczi termed this “obstetrical thought assistance.” They disregarded childhood memories, believing that it was more economical and just as therapeutically valuable for patients to act out and relive their traumas in the interaction of the transference situation. “We see the process of sublimation, which in ordinary life requires years of education, take place before our eyes,” Rank wrote with new therapeutic optimism.76

Though Freud described Ferenczi and Rank’s efforts as a “fresh daredevil initiative,” he was suspicious of the quick cures they promised.77 Freud had had his beard shaved off before his cancer operation, and it had taken six weeks to grow back. Three months later the scar had yet to heal. Wouldn’t it take a bit longer than a scar takes to heal, he asked cynically of Ferenczi and Rank’s work, to penetrate to the deepest levels of the unconscious? Their practice sparked a controversy between progressive and more traditional analysts; the British analyst Edward Glover, a proponent of passive therapy who believed that shaking hands with patients might provoke needless emotional contagion, was the most vocal defender of orthodoxy. It is important to stress, however, that Ferenczi and Rank were not doubters but zealous reformers in psychoanalysis’s name— as was Reich. They found fault with classical analysis only because they had higher hopes for analysis itself.

Freud expressed concern that active therapy might be “a risky temptation for ambitious beginners.”78 Reich, disappointed with the “[Egyptian] mummy-like” attitude required of him in passive analysis, was one of the “ambitious beginners” drawn to Ferenczi and Rank’s cutting-edge and more dynamic technique. He sought to fuse their innovations with Abraham and Jones’s parallel developments in characterology and with his own theory of the orgasm, a synthesis that culminated in his book Character Analysis (1933). Reich later claimed that in 1930, the year he left for Berlin, Freud had credited him with being “the founder of the modern technique in analysis.”79 Reich is indeed almost universally acknowledged as the founder of a new method of analyzing a patient’s defenses, a technique that evolved into what became known as ego psychology. This was the dominant therapeutic practice in the 1950s, especially in the United States, where Character Analysis became a standard training manual for many years— though it was employed in the States to very different ends from those for which Reich first imagined it.

Reich shifted the focus from what the patient told him in analysis to how it was said. He would be deliberately provocative and confrontational with his patients. Instead of dissolving the traumatic nature of childhood events by going over them in words again and again, as an orthodox analyst would do, Reich would seize upon physical evidence of a resistance and goad the patient with his observation of his or her resistances (Ferenczi had referred to his own brand of dynamic psychoanalysis as “irritation therapy”). “We confront . . . the patient with it repeatedly,” Reich stated, explaining how he sought to puncture the defensive shield of the patient’s ego—or, as he termed it, “character armor”—“until he begins to look at it objectively and to experience it like a painful symptom; thus, the character trait begins to be experienced as a foreign body which the patient wants to get rid of.”80

Reich thought that patients were always producing material that could be interpreted; even their silences revealed a mutating façade of resistance, Reich believed, and he was very attentive to these awkward phenomena. Reich used to act out for his students the various nonverbal clues, facial expressions, and bodily postures with which neurotic patients revealed this emotional barrier: “the manner in which the patient talks, in which he greets the analyst or looks at him, the way he lies on the couch, the inflection of his voice, the degree of conventional politeness.”81 In so doing, he transferred Freud’s cerebral notion of resistances to the body.

One of Reich’s patients, Ola Raknes, praised Reich’s undisputable therapeutic gift:

As a therapist he was naturally and absolutely concentrated on the patient. His acuity to detect the slightest movement, the lightest inflection of the voice, a passing shadow of a change in the expression, was without a parallel, at least in my experience. And with that came a high degree of patience, or should I call it tenacity, in bringing home to the patient what he had discovered, and to make the patient experience and express what has not been discovered. Day after day, week after week, he would call the patient’s attention to an attitude, a tension or a facial expression, until the patient could sense it and feel what it implied.82

The American psychiatrist O. Spurgeon English visited Reich’s fourth-floor apartment near the General Hospital teaching hospital seven days a week for therapy:

It was at this time that I recall Dr. Reich utilizing his interest in other than verbal presentations of the personality. For instance, he would frequently call attention to the monotony of my tone of voice as I free associated. He would also call attention to my position on the couch, and I remember particularly that he confronted me with the fact that when I entered and left the office, I made no move to shake hands with him as was the custom in both Austria and Germany.83

English found Reich “taciturn” and “cold and unfriendly,” and he was encouraged by Reich to voice these criticisms; in their sessions English complained of Reich’s chain-smoking and his habit of interrupting the analysis to take frequent phone calls, and his suspicion that Reich insisted on such an intensive schedule of treatment only because he wanted to relieve him all the more speedily of his dollars. Despite their frequent arguments, in the end English was enthusiastic about his therapy, concluding that Reich was “serious . . . although not without humor.”84 English wrote in an essay on Reich (one can almost hear English’s monotonous tone): “I have always felt a great gratitude that somehow or other I landed in the hands of an analyst who was a no-nonsense, hard-working, meticulous analyst who had a keen ear for the various forms of resistance and a good ability to tolerate the aggression which almost inevitably follows necessary confrontation in subtly concealed or subtly manifested resistance.”85

Reich believed that unless patients were provoked into expressing their pent-up hatred of him, he wouldn’t be able to clear up their resistances; no genuine positive transference would be achieved and the analysis would invariably falter. A humanitarian optimism underlay Reich’s new therapeutic scheme that wasn’t immediately apparent in his aggressive practice. In Reich’s onion-like model of the psyche, man is inherently good, with a loving and decent core of “natural sociality and sexuality, spontaneous enjoyment of work, capacity for love” (the id). However, this is sheathed in a layer of spite and hatred, the residue of all our frustrations and disappointments (the realm of the Freudian unconscious). We protect and distract ourselves from these horrors with a third and final layer of “character armor,” he believed, an “artificial mask of self-control, of compulsive, insincere politeness and of artificial sociality” (the ego— the buffer between the id and the outer world, or superego). Freud thought that the ego was the locus not only of resistance but also of reason and of the necessary control of the instincts; Reich, in contrast, thought the instincts were good, if only we could bypass the ego’s resistances. In therapy, he wanted to smash through to the garden of Eden that he thought we all harbored deep within us.

Using a metaphor from his farm days, Reich explained:

Human beings live emotionally on the surface, with their surface appearance . . . In order to get to the core where the natural, the normal, the healthy is, you have to go through the middle layer. And in the middle layer there is terror. There is severe terror. Not only that, there is murder there. All that Freud tried to subsume under the death instinct is in that middle layer. He thought it was biological. It wasn’t. It is an artifact of culture . . . A bull is mad and destructive when it is frustrated. Humanity is that way, too. That means that before you can get to the real thing— to love, to life, to rationality— you must pass through hell.86

According to the psychoanalyst Martin Grotjahn, who knew Reich in the 1920s, Reich was known by his colleagues as “the character smasher.” Of his analytic technique Reich wrote, “I was open, then I met this wall— and I wanted to smash it.” Reich hoped to free the reservoir of libido that the ego had frozen over, so that the patient could achieve the curative warmth of total orgasm. To that end, Reich asserted, the therapist had to be “sexually affirmative,” open to “repressed polygamous tendencies and certain kinds of love play.”87

Naturally, the patient didn’t like being perpetually reminded of his weaknesses, and frequently acted aggressive in the face of Reich’s sometimes abusive and excessively authoritarian method. Richard Sterba remembered that “Reich became more and more sadistic in ‘hammering’ at the patient’s resistive armor.”88 He suggested that his therapeutic emphasis reflected not simply the theoretical development of a technique but Reich’s “own suspicious character and the belligerent attitude that stems from it.”89

The year before it was published, Reich presented to Freud the manuscript of his major work, The Function of the Orgasm, for his seventieth birthday ( May 6 , 1926), inscribing it to “my teacher, Professor Sigmund Freud, with deep veneration.”90 Freud’s sarcastic response to Reich’s 206-page tome was “That thick?”— as if to suggest that the function of the orgasm was rather self-evident. Freud evidently didn’t share Reich’s belief in the potent orgasm as the summation of human health. Two months later he wrote Reich a tardy but polite note: “I find the book valuable, rich in observation and thought. As you know, I am in no way opposed to your attempt to solve the problem of neurasthenia by explaining it on the basis of genital primacy.”91

Freud adopted a more acerbic tone when he wrote to the psychoanalyst Lou Andreas-Salomé in Berlin: “We have here a Dr. Reich, a worthy but impetuous young man, passionately devoted to his hobbyhorse, who now salutes in the genital orgasm the antidote to every neurosis. Perhaps he might learn from your analysis of K. to feel some respect for the complicated nature of the psyche.”92 K. was one of Lou Andreas-Salomé’s hysterical patients who seemed to refute Reich’s claims; K.’s sex life revealed, according to AndreasSalomé, a “capacity for enjoyment, a spontaneous and an inner physical surrender such as in this combination of happiness and seriousness is not often to be met with.”93

In the summer of 1926, Reich again put himself forward as a candidate for second secretary of the Vienna Psychoanalytic Society. This time Federn abolished the position without explanation. Reich wrote Federn a letter, which he never sent, to complain about what he felt was a definite slight. He only sought the appointment, he wrote, because he wanted to see and hear Freud more frequently: “infantile, perhaps, but neither ambitious nor criminal,” he argued. “My organizational work in the Society, combined with my scientific activity, gave me the sense of justified expectation.”94 He admitted to having been “stung by an irrelevant scientific opposition” to his ideas, and to having perhaps been overdefensive in the face of criticism: “I never intended any personal offense,” Reich wrote in protest, “but always objectively said what I was convinced I was justified in saying— without false consideration, however, for age or position of the criticised party.”95

In a letter that he subsequently wrote to Freud, Reich complained of Federn’s “hateful, high-handed tone” and “supercilious condescension.”96 Reich didn’t send this letter either, though he evidently hoped for some sympathy; in an indiscreet moment at the Ambulatorium, Hitschmann had told Reich, to the latter’s satisfaction, that Freud had commented that Federn had “patricidal eyes.”97 Reich chose to complain about his treatment at the hands of Federn in person instead. After Reich visited him for this purpose, Freud wrote Reich a letter, dated July 27 , 1926, assuring him that any personal differences between him and Federn would not influence his own high regard for Reich’s competence, a view that he said was shared by many others.98

Though Freud had defended Reich against Federn two years earlier, by this time he had transferred his paternal attention to two fresh protégés, Franz Alexander and Heinrich Meng. The latter was editing a popular manual of psychoanalysis with Federn. Freud humiliated Reich by cutting him down in public at one of his monthly meetings, revealing his new impatience with the cantankerous twenty-nine-year-old. After Reich gave a talk in December 1926 in which he argued that every analysis should begin with a discussion of the patient’s negative transference, Freud, who had decided that his “classical technique” was superior to the proposed innovations of Ferenczi, Rank, and Reich, interrupted, “Why would you not interpret the material in the order in which it appears? Of course one has to analyze and interpret incest dreams as soon as they appear.”99 His “biting severity,” as Reich called Freud’s response, sent out a clear signal to all that Reich had fallen out of favor.

“I was regarded very highly from 1920 up to about 1925 or 1926,” Reich recalled in 1951 when speaking to Kurt Eissler, the founder and keeper of the Sigmund Freud Archives, who was compiling an oral history of Freud and his circle. “And then I felt that animosity. I had touched on something painful— genitality. They didn’t like it.”100 Until then Reich had thought of himself “as a sincere and unhesitating champion of psychoanalysis,” completely dedicated to what Freud called “the cause.”101 Now he was increasingly aware that he had largely alienated his psychoanalytic colleagues with his dogged insistence that everyone lay their patients bare to the pleasures of “ultimate involuntary surrender.”