Читать книгу DAIWI - Chuck Pfeifer - Страница 3

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

INTRODUCTION

ОглавлениеHanoi 1993. The best and the brightest were in Vietnam again, and so was I.

Twenty-five years earlier, in some ways, this phrase described me. In 1968, I may not have been the best or the brightest, but I was certain I stood next to them. Not because I was a Special Forces Captain, a West Point graduate, football player, Ivy League dropout, or that I came from a Park Avenue penthouse. It was because in Vietnam I was free. In 1968, virtually without constraint, I roamed the jungles, cities, and mountain towns of Vietnam and Laos for nine months. I picked up scraps of newspaper in Da Nang whorehouses or the Saigon Bachelor Officer Quarters and read about the Summer of Love in the USA, about this or that—live and laugh.

I spent years earning the right to be there: Airborne, Ranger, and Pathfinder schools, at Fort Benning, and with the U. S. 10th Special Forces in Bad Tolz, Germany. I trained alongside the British Special Air Service (SAS), French Marine Commandos (the equivalent of U. S. Navy SEALS), Deutsch Kampfschwimmers (German Special Forces), Special Forces Legionnaires (French Foreign Legion), Danish Jaeger Forces (Elite Special Forces Unit of the Royal Danish Army), and the Hellenic Raiders (Elite Greek 1st Raider/Paratrooper Brigade). These were the killer elite of every western war from Hitler on. For me, freedom came down to one word: meritocracy. It made every human construct from politics and economics to ethics and metaphysics seem pale, powerless, and virtually without value.

Only a few top military or government officials had heard of a top-secret group that became an important part of my life when I graduated West Point’s “Long Gray Line” in 1965. In 1964, the Joint Chiefs of Staff created an organization named SOG, as a subsidiary to the Military Assistance Command. An unconventional warfare task force, this group would be used in top-secret and cross-border reconnaissance operations in Cambodia and Laos in the Vietnam War. SOG consisted of soldiers from all branches of the military, including recon men and special operations pilots of the 90th Special Operations Wing, but predominately Army Special Forces. However, in March 1965, just a month or so before my graduation, SOG’s Saigon headquarters very quietly celebrated finally being allowed to penetrate the Ho Chi Minh Trail, a highly strategic and important move. I had no way to know I would become a part of the secret forages and battles in forbidden Laos under the SOG banner. Had I known, my core would have recoiled in protest and fear, but I would have gone and done what I could for my country. General George C. Marshall, Chief of Staff, U.S. Army, World War II, said: “I want an officer for a secret and dangerous mission. I want a West Point Football Player.” I was.

On March 8, 1965, the very first American combat troops from the 3/9 Marine Battalion came ashore on the beaches just Northwest of Da Nang. The event was televised and the arrival was met with a boisterous show of support from sightseers: South Vietnamese officers, Vietnam girls with leis, and four American soldiers with signs reading, “Welcome Gallant Marines.” General Westmoreland, Senior U.S. Military Commander in Saigon was appalled. He had hoped to keep the landing as quiet as possible.

When I finally arrived in Saigon and went to war, the campaign that America called the TET offensive was winding down. Vietnam called it The War Against Americans To Save the Nation, or the American War. The Communist TET offensive was two-fold: To create unrest in South Vietnam’s populace and to cause the U. S to scale back its support of the Saigon regime, or cause complete U. S. withdrawal. In an attack planned by General Vo Nguyen Giap, over 100 cities in South Vietnam were attacked by over 70,000 Communist troops. General Giap was thought by many to be one of the greatest politicians and military strategists of the 20th Century. Militarily, TET was a failure for the North Vietnamese Army and the rebel Viet Cong, although it was a strategic victory. American media wrongly portrayed the TET offensive as a Communist victory. Liberal propaganda was instrumental in turning the American populace against this long and bloody War. TET was not just about winning short-term battles. It proved to be an American political turning point in the war, leading to the slow withdrawal of United States troops from the region.

Warfare had gone from permanent (Uncle Ho’s) to ugly (ours) to unconditional. There is simply no greater meritocracy. I was headed to the very unconditional I Corps, a member of SOG: the Project. SOG was a typically polite acronym (Studies and Observation Group) for a network of reconnaissance, saboteurs and assassins led by Colonel (later Major General) John Singlaub. The Joint Chiefs of Staff implemented the Project in 1964, as a subsidiary of the Military Assistance Command (MACV), during the secret war against Laos. The enemy terrain, and the obscure nature of civil war made it clear we badly needed covert activity. SOG had since become one of the backbones of the official war as well (it was a SOG operation, for example, that precipitated the Gulf of Tonkin), with Vietnam as our official mandate. To bastardize Melville, it was always Laos, though, that was my “Yale and Harvard.”

The Americans named the Ho Chi Minh Trail after the North Vietnamese president. The Communists called it the Truong Son after the Annamite Mountain Range in central Vietnam that runs from North Vietnam to South Vietnam, through Laos and Cambodia. The Trail was strategic for enemy communications and the transport of supplies during all wars in Vietnam. Part of what became the Trail had existed for centuries as primitive footpaths to facilitate trade in the region. The U. S. National Security Agency’s official history of the Vietnam War stated that the Ho Chi Mihn Trail was one of the greatest achievements in military engineering.

Vietnam was divided into four corps of tactical political and military jurisdictions. I Corps, in the northernmost region of the country, covered 10,000 square miles and abutted Laos on the west and enemy bases supplied via the Ho Chi Minh Trail. The number of North Vietnam troops was estimated around 78,000 in I Corps, with about half of them around the DMZ. The next largest number was massed around Da Nang and could attack from either direction and could shell northern Quang Tri from North Vietnam and Laos. I Corps bordered the DMZ as well. Of the four tactical zones, I Corp, because of its location, was most likely to be attacked and hardest to protect or defend.

I was assigned to I Corps, close to Marble Mountain. Marble Mountain has approximately 156 steps to the top, and I commanded soldiers up those steps many times. The terrain around I Corps favored the enemy. Rolling piedmont gave way to flat wetlands, mostly covered with rice paddies. Beyond that, the sands of the South China Sea stretched long and hot. Most of the Vietnamese inhabitants in the I Corps area lived in the hamlets and villages interspersed around the rice fields or in the large cities of Hue and Da Nang. The enemy’s political agents and guerrilla fighters were living and operating among the citizens and could easily obtain recruits and supplies. They still lived there, but I am certain it became much harder for them to obtain supplies after we showed up to interdict their operations. Much, much, harder.

II Corps comprised the Central Highlands, III comprised a densely populated region between Saigon and the Highlands, and IV comprised the marsh Mekong Delta, in the southernmost region.

As a direct result of the Geneva Conference, in a peacemaking effort between North and South Vietnam, the DMZ (demilitarized zone) was established and finalized in July 1954, at the end of the 8-year First Indochina War. The combat-free zone, also known as the 17th parallel, was a five kilometer, or a little over three-mile area, and ran east and west, separating North and South Vietnam. During the Second Indochina war (Vietnam War) the north part of Vietnam became known as the Democratic Republic of Vietnam. It was controlled almost entirely by the Communist Viet Minh, under the leadership of Ho Chi Minh. The south part of Vietnam became known as the independent State of Vietnam, first under the leadership of Bao Dai beginning in 1926. The State of Vietnam later became the Republic of Vietnam. As one can readily see, Vietnam was, and undoubtedly still is, a study in complicated politics.

During the 1940s and 1950s the United States and Britain collaborated on the development of herbicides for possible use in war. The British were the first to use these herbicides when the Malayan Communist Party attempted an overthrow of the British colonial administration. This resulted in a 12-year war from 1948-1960, named the Malayan Emergency, in which the British prevailed.

There are differing estimates, but at least 20 million gallons of herbicides of varying components were sprayed to defoliate crops and trees during the Vietnam war. At least 12 million gallons, or 60%, of these herbicides were Agent Orange (AO), so named because of its striped orange storage barrels. Spraying was primarily done by specially equipped helicopters, or low-flying C-123s, under the call name “Hades,” and lasted from 1962 through 1971. Millions of acres in Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia were affected by this program named Operation Ranch Hand. AO had two components including Tetrachloro-dibenzopara-dioxin, and thought to be many times greater than the level approved by the United States Environmental Protection Agency. There were nine major producers of AO, most notably Dow and Monsanto. They claimed not to know the dangers of Dioxin. It is believed Dioxin can remain in humans for 11 to 15 years and in protected-from-sun soil for up to 100 years, and is not soluble in water. AO is no longer produced. Hundreds of thousands of Vietnam citizens and U. S. Vietnam veterans still suffer the effects of these extremely dangerous herbicides, especially AO. Vietnam veterans have a high incidence of health issues, such as throat cancer, liver diseases, Hodgkins’ disease, lung cancer and colon cancer. Certain mental conditions, as well as birth defects, have also been detected and may be related to AO exposure.

The United States military dropped more bombs on North Vietnamese Army-occupied Eastern Laos during the Vietnam war than were dropped on Germany and Japan combined during WWII. There are still unexploded ordnances in large parts of those countries.

The nature of the Vietnam War made it virtually impossible to know for sure, but the United States estimates that 200,000 to 250,00 South Vietnamese soldiers perished. Over 2,000,000 civilians, on both sides were killed. 58,000+ U. S. soldiers died and 304,000 were wounded. 1.1 million Viet Cong and North Vietnamese were killed, with thousands wounded. These figures include the Missing in Action. General Giap may have been right when he said, “It was a people’s war.”

In the Vietnam War, a commander was assigned a call name to distinguish him from a radioman. My call name was “Waterbird” from my first mission to my last, no matter my location or mission. I hoped I would not have to use it, but I knew I would. I could not imagine completing many missions without having to call in a Prairie Fire or two.

February 1968, was the first time I had been called “Waterbird.” I was in the company of a couple of experienced SOG officers in an H-34 helicopter flying over Laotian mountain passes. They loved to show off to new members and subject them to theretofore-unknown fear. I was no exception. I sat with my feet close to the open side of the chopper, and watched tracers the size of footballs fly past, and smelled the trailing phosphorus disappear into the sky. “Waterbird,” one of the officers yelled over the roar, “Better get back.” There was no place to hide, so I backed up and prayed we did not go down. There were just the two SOG officers and me, and they had been through it more than a few times. They were laughing their heads off, but they quickly stopped laughing when a couple of 12.7mm rounds came too close to the chopper. I was genuinely scared, but these guys were not going to know it. No way in hell.

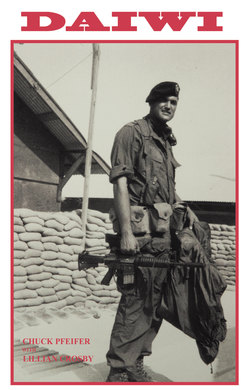

My role as Captain (Daiwi) was to command a battalion of Nungs that could be as many as 1000, but mine numbered 200. Indigenous Nungs, Montagnards and Cambodes were CIA-recruited. Many Nungs had come to Vietnam from China’s southern area of Kwangsi Province around the Highlands area of NV. The Montagnards were often referred to as hill people and “Yards.” They did not particularly fight for money, but they were well paid by the United States government, under the auspices of the CIA. The Chinese Nungs had been exiled by Mao in the early 1950s, and worked primarily around the Ho Chi Minh Trail. They were sometimes called “indigs” and sometimes the “fat ones,” although they were much smaller in stature than most U.S. soldiers. They hated the Vietnamese and the Chinese, and were hated in return. As a result, the Nungs were perfect to fight for the United States. Ferocious, fearsome, loyal, clever and brutal, they fought to the death. The bond between us quickly became very strong, due in part by necessity on both sides. The United States Army needed their trust, support and extremely good fighting abilities, and they needed our guidance and teaching. We had learned to communicate - they in broken English, and I in broken Vietnamese or Nung, facial expressions, hand gestures, and a lot of initial frustration. Most of them could not count beyond three, and I was amazed at how fast they learned.

I consider myself a “universal” soldier, although, obviously, I do not personally know every solider who served in our wars. But I respect their service more than I can ever express. I identify with their struggles. I have had the same experiences, the same gnawing sickness and acute anxiety. I see the same devouring images and have the same thoughts that sometime make us nearly strangers to all who love and know us best. With my eyes wide open, in my sleep and in my nightmares, I still see the faceless men with severed limbs, burns, and mental scars. I have felt the spit of disenchanted and ill-informed American citizens who blamed some of America’s bravest for serving in the Vietnam War. Maybe, I think, this has hurt more than anything else. I suppose they just could not understand or relate to what the soldiers had been through. I fought for their freedoms, or at least thought I did. If there is any fault, it does not lie with brave veterans, but with the government who sent them there. I would fight again if called upon. I would, however, hope it is a war that needs to be fought and that our country goes in with the dedication needed to win it.

In Vietnam, I awoke many mornings with the same conviction: Fuck this. Go home. But I was a soldier and a good one, and I knew there was only one way to fight a battle, even when the territory was internal like Vietnam: eyes wide open, straight ahead. There is nothing left for me in New York anyway if I don't face this here. I headed back to I Corps.

My favorite quote about war comes from Nietzsche: “Nothing like a good war to make life so . . . personal.” My Vietnam was so personal. I wrote my own rules while fighting in my enemy’s backyard. I was a demigod in charge of everyone, already a servant to power. At times, however, I found myself a servant to powerlessness, too

When I began to write this autobiography, I chose not to write a “war” book. Instead, I chose to bring the reader into a world of privilege and into the pain, fear, and impact of indelible memories before, during, and after the hell of war. I chose to include a few battles because I felt they were important to who I am and to the theme of the book. A few battles were major, some not, and some were merely incidental. With Vietnam far behind me, at least physically, I am still called Waterbird or Daiwi by a good number of my friends and acquaintances.