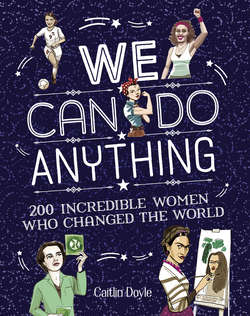

Читать книгу We Can Do Anything: From sports to innovation, art to politics, meet over 200 women who got there first - Chuck Gonzales, Caitlin Doyle - Страница 16

ОглавлениеJUANA INÉS DE LA CRUZ AUTHOR, ACTIVIST, AND EARLY FEMINIST

FULL NAME: Juana Inés de la Cruz

BORN: NOVEMBER 12, 1651, SAN MIGUEL NEPANTLA (NOW TEPETLIXPA), MEXICO

DIED: APRIL 17, 1695, MEXICO CITY, MEXICO

NATIONALITY: MEXICAN

“I don’t study to know more, but to ignore less.”

JUANA INÉS DE LA CRUZ

TEENAGE WONDER

Almost 400 years ago, Juana Inés de la Cruz was her generation’s Malala (see here). An outspoken activist for women’s right to an education, Juana’s scholarly work became known throughout Mexico—and as far as Spain—when she was still a teenager. Aged 16, Juana decided to become a nun in Mexico City, as it would give her the freedom to study and write. At the time, living as a nun was one of the only options for a girl who wanted to pursue these activities. As a nun, Sor (Sister) Juana wrote poetry, plays, and essays, challenging social norms and defending women’s rights. Juana found her own access to education—as she was entirely self-taught. From 1669 until the end of her life, Juana lived at the Convent of Santa Paula, where she wrote, taught music and drama, composed music, and worked as the convent’s accountant and archivist. She built up one of the largest private libraries in the New World. (The “New World” was an early European name for the Americas.)

THE TENTH MUSE

Unlike many writers and artists throughout history, Juana was successful in her lifetime, during the Golden Age of Spanish arts. Her nickname was the “Tenth Muse.” She was a very talented writer and set her hand to many different genres and styles. She was also the unofficial royal court poet in the 1680s. The characters in her plays included women who were both brave and clever, and her religious works praised the learned female saints. Eventually, the Church disapproved of her writing and her beliefs, instructing her to focus on religious studies. However, Juana defended herself admirably, while also asserting all women’s right to knowledge: “One can perfectly well philosophize while cooking supper.”

Juana has lived on as a lasting icon of many things: Mexican identity, early feminism, and independence. In the 20th century—thanks, in part, to the work of Mexican artists Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo (see here) and contemporary artists—Juana became famous again. (She can be seen in Rivera’s 1947 mural, Dream of a Sunday Afternoon in the Alameda Central in Mexico City, Mexico.) Her ideas and accomplishments were ahead of their time, but the world has finally caught up. She is credited as the first published feminist of the New World and an outstanding writer of her period. Today, Juana’s portrait is on Mexican currency and she remains an inspiration to modern artists, scholars, and feminists.

A statue of Sister Juana Inés de la Cruz, given from Mexico to Madrid, Spain in 1981

| FABULOUS FIRSTS | |

| FIRST PUBLISHED FEMINIST OF THE “NEW WORLD” |