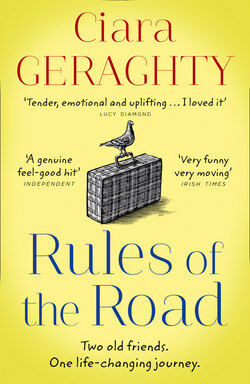

Читать книгу Rules of the Road - Ciara Geraghty - Страница 7

2 YOU MUST ALWAYS BE AWARE OF YOUR SPEED AND JUDGE THE APPROPRIATE SPEED FOR YOUR VEHICLE.

Оглавление‘The speed limit on a regional road is eighty kilometres per hour,’ Dad says.

‘Sorry, I’m … in a hurry.’ I glance in the rear-view mirror. I think I hear sirens, but I see no police cars behind me.

In my peripheral vision, Iris’s letter, in a crumpled ball at the top of my handbag.

My dearest Terry,

The first thing you should know is there was nothing you could have done. My mind was made up.

Panic is spinning my thoughts around and around, faster and faster, until it’s difficult to make out individual ones.

‘Did I ever tell you about the time I had Frank Sinatra in the taxi?’ says Dad.

‘No.’ Most of my conversations with my father are crippled with lies.

‘It was a Friday night, and I was driving down Harcourt Street. The traffic was terrible because of the … the stuff … the water …’

‘Rain?’

‘Yes, rain and …’

The second thing you should know is there was nothing you could have done. My mind was made up.

The lights are red and I jerk to a stop. The brakes screech. The car is due for an NCT next month. I need to get it serviced before then. Brendan says I should get a new one. A little run-around, he says. Something easier to park. But I like the heft of the Volvo. It’s true that it’s nearing its sell-by date. Maybe even past it. But I feel safe inside it. And it’s never let me down.

‘… and I said to Frank I know the words to all your songs and …’

… but please know that this is a decision I have come to after a long, thorough thought process and I do not and will not regret it.

I’ve never been to Dublin Port before. I park in a disabled spot. I have no permit to do so.

‘Dad, will you stay here? I have to … I have to do something.’

‘Of course, love, no problem.’

‘Promise me you won’t get out of the car?’

‘Are you going to pick up your mother?’

‘Swear you’ll stay here ’til I get back.’

… and perhaps it is too much for me to ask; that you understand my choice, but I hope you do because your opinion is important to me and …

My father looks at me with curiosity as if he’s trying to work out who I am, and perhaps he is. It is sometimes difficult to tell what he knows for sure and what he pretends to remember.

I bend towards him, put my hand on his shoulder. ‘I’ll be back soon, okay?’

He smiles a gappy smile, which means he’s taken out his dentures again. Last time I found them inside one of Anna’s old trainers in the boot.

‘You’ll be back soon,’ he says, and I tell him I will, and close the door and lock him into the car.

… practical arrangements have been taken care of with the clinic in Switzerland and are enclosed for your …

If the car catches fire, he won’t be able to get out. He’ll be burned alive. Or suffocated with the smoke. But the car has never caught fire, so why would it today? Of all days? I hesitate. Brendan would call it dithering.

… only a matter of time before that happens, which is why it needs to be now, before I am no longer able to …

I run through the car park, towards the terminal building. I try not to think about anything. Instead, I concentrate on the sound of my soles thumping against the ground, the sound of my breath, hot and strained, the sound of my heart, thumping in my chest like a fist.

My dearest Terry,

The first thing you should know is …

I spot Iris immediately. She’s easy to spot even though she’s not all that tall. She seems taller than she is.

The relief is palpable. Solid as a wall. She’s in a queue, doing her best to wait her turn. She does not look like a woman who is planning to end her life in a clinic in Switzerland. She looks like her usual self. Her steel-grey hair cropped close to her scalp, no make-up, no jewellery, no nonsense. It’s only when the queue shuffles forward, you notice the crutches, and still, after all this time, they seem so peculiar in her big, capable hands. So unnecessary.

I stand for a moment and stare at her. My first thought is that Iris was wrong. There is something I can do. What that something is, I haven’t worked out yet. But the fact that I’m here. That’s she’s still here. I haven’t missed her. It’s a Sign, isn’t it?

The relief is so huge, so insistent, there’s no room for any other feeling in my head. I’m full to the brim with it. I’m choking on it. My voice sounds strange when I call her name.

‘Iris.’ She can’t hear me over the crowd.

I walk nearer. ‘Iris?’

‘IRIS!’ Heads turn towards me, and I can feel my face flooding with heat. I concentrate on Iris, who turns her face towards me, her wide, green eyes fastening on me.

‘Terry? What the fuck are you doing here?’

Iris’s propensity to curse was the only thing my mother did not like about her.

My mouth is dry and the relief has deserted me and my body is pounding with … I don’t know … adrenalin maybe. Or fear. I feel cold all of a sudden. Clammy. I step closer. Open my mouth. What I say next is important. It might be the most important thing I’ve ever said, except I can’t think of anything. Not a single thing. Not one word. Instead, I rummage in my handbag, pull out her letter, do my best to smooth it so she’ll recognise it. So she’ll know. I hold it up.

When Iris sees the page, she sort of freezes so that, when the queue shuffles forward, she does not move, and the person behind – engrossed in his phone – walks into the back of her.

‘Oh, sorry,’ he says. Iris doesn’t glare at him. She doesn’t even look at him, as if she hasn’t noticed his intrusion into her personal space, another of her pet hates. Instead, she nudges her luggage – an overnight bag – along the floor with a crutch, then follows it.

I stand there, holding the creased page.

People stare.

I lower my hand, walk towards her.

‘What are you doing?’ I hiss at her.

She won’t look at me. ‘You know what I’m doing. You read my note.’ She concentrates on the back of the man’s head in front of her. The collar of his suit jacket is destroyed with dandruff.

I fold my arms tightly across my chest, making fists of my hands to stop the shake of them. I should have thought more about what I was going to say. I don’t know what I thought about in the car. I don’t think I thought of anything. Except getting here.

And now I’m here, and I can’t think of what to say. Or do.

‘Iris,’ I finally manage. ‘Say something.’

‘I’ve explained everything in my letter.’ She looks straight ahead, as though she’s talking to someone in front of her. Not to me. People in the queue crane their necks to get their fill of us. ‘I’ve read it,’ I say, ‘and I’m none the wiser.’

‘I’m sorry, Terry.’ She lowers her head, her voice smaller now. A crack in her armour that I might be able to prise open.

I put my hand on her arm. ‘It’s okay, Iris. It’s going to be okay. We’ll just get into my car. I’m parked right outside. Dad’s in the car by himself so we need to …’

‘Your dad? Why is he here?’

‘There’re rats. In Sunnyside. Well … vermin, which I took to mean … but look, I’ll tell you about it in the car, okay?’

‘How did you know I’d be here?’ Iris says.

‘I saw the booking form. On your computer.’

‘You hacked into my laptop?’

‘Of course not! You left your computer on, which, by the way, is a fire hazard. Not to mention the security risk of not having a password.’

‘You broke into my house?’

‘No! I used the key you keep in the …’ I lower my voice ‘… shed.’

The queue shuffles forward, and Iris prods her bag with her stick, follows it. She is nearly at the head now.

‘Iris,’ I call after her, ‘come on.’

‘I’m sorry, Terry,’ she says again, looking at me. ‘I’m taking this boat.’ Her voice is filled with the kind of clarity nobody argues with. I’ve seen her in action. At various committee meetings at the Alzheimer’s Society. That’s another thing she hates. Committees. She prefers deciding on a course of action and making it happen. That’s usually how it pans out.

I stand there, my hands dangling uselessly from the ends of my rigid, straight arms.

‘I am not going to allow you to do this,’ I say then.

‘Next,’ the man at the ticket office calls.

Iris bends to pick up her overnight bag. I see the tremor running like an electrical current down the length of her arm. I know better than to help. Anyway, why would I help? I’m here to hinder, not to help.

I’m not really a hinderer, as such.

Iris says I’m a facilitator, but really, I just go along with things. Try not to attract attention.

Iris hooks her bag onto the handle of the crutch, strides towards the man at the hatch. Even with her sticks, she strides.

I stumble after her.

‘I’m collecting a ticket,’ she says. ‘Iris Armstrong. To Holyhead.’

The man pecks at his keyboard with short, fat fingers. ‘One way?’ he asks.

Iris nods.