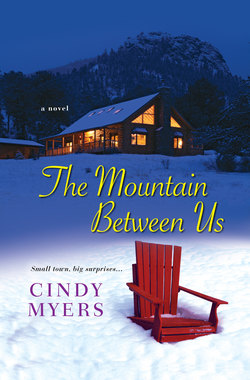

Читать книгу The Mountain Between Us - Cindy Myers - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER ONE

Maggie Stevens stared out the front windshield of the Jeep, at the mountainside ahead painted with golden aspen, maroon rock, and purple aster—as if fall were playing a game of “top this” with summer, decorating itself with even more beautiful color. A lot of people probably came to this overlook above Eureka, Colorado, to try to deal with life’s big questions, to let the hugeness of the mountains lend perspective.

Really, she’d only driven up here because the cell phone reception was best.

She glanced at the plus sign on the little plastic strip in her hand again. “Maybe the test is defective,” she said into the phone. “Maybe that’s why it was for sale at the dollar store.”

“You bought a pregnancy test at the dollar store?” On the other end of the line her best friend, Barb Stanowski, sounded very far away.

“I certainly wasn’t going to buy it here in town.” If anyone had seen her with her purchase at Eureka Grocery, the news would have been all over town before she even got back to her place. So she’d driven half an hour up the road to Montrose. “And I couldn’t bring myself to pay ten dollars for something I was going to pee on. Besides, I needed three of them.”

“Three?” Barb was laughing again.

“I wanted to be absolutely sure. What if they’re wrong?”

“All three of them? Not likely. How are you feeling?”

“I told you. Sick. Scared. And kind of elated.” Her first husband had refused to consider the idea of children. When he’d left her shortly before her fortieth birthday, she’d resigned herself to never having the baby she’d always wanted. Then she’d met Jameso and now . . .

“Any physical symptoms?” Barb asked.

“My breasts are really sensitive. I’ve been throwing up, but not just in the morning. Yesterday, Janelle brought onion rings with my lunch. I love her onion rings, but one whiff of those and I had to leave the café. And Rick told me I was glowing.”

“Your boss told you you were glowing? Have you been around any leaking nuclear reactors lately?”

“He was teasing me.” Rick Otis, editor and publisher of the Eureka Miner, made a hobby out of getting people’s goat. “He said I must be in love, because I was positively glowing.”

“You are in love, aren’t you?”

“Yes, maybe. I mean, yes, I love Jameso, but he’s not exactly responsible father material.” Handsome, sexy, unpredictable Jameso Clark, who’d roared into her life on a motorcycle on her very first night in Eureka. He’d made her feel alive and sexy and hopeful again after the emotional wreckage of her divorce.

“How can you say that, if he cares about you and the baby?” Barb liked Jameso. She’d liked him before Maggie did, and continued to see qualities in him Maggie couldn’t.

“He’ll probably freak out when I tell him about the baby.” Maggie shuddered. She pictured him climbing on his motorcycle and riding away, out of her life forever. “I do love him. I think he’s great, but I don’t have any illusions about him. He’s a part-time bartender slash ski instructor slash mountain guide, whose most valuable possession is a motorcycle. He’s estranged from his family, and he probably suffers from post-traumatic stress, though he won’t admit it.” Jameso refused to talk about his time in Iraq and turned away if she tried to question him.

“I think you’re underestimating him,” Barb said. “This may be just what he needs to turn his life around. He’ll probably make a great father.”

“What about me? What kind of mother will I be?” Maggie allowed herself to give in to the panic a little. “I don’t know anything about children. I’ve never spent any time around them. I’m forty years old. I’ll be ready to retire when this baby graduates college.” She closed her eyes, fighting a wave of dizziness.

“Calm down. Lots of women in their forties have babies these days. And you’ve always wanted children. You’ll be a great mom.”

“Barb, I’m scared.” She opened her eyes again, shifting her gaze until she found the top of Mount Winston. How many mornings now had she awakened to the sight of that towering peak since coming to Eureka from Houston five months ago? She’d come here intending to stay a week—two at the most—gathering her late father’s effects and trying to learn as much as she could about the man who’d walked out of her life when she was only a few days old. But the mountains had pulled at her, refusing to let her leave. Of all the things her father had left her, his greatest gift had been that new perspective on her life and the chance to start over with a different vision.

Was a baby part of that vision? Apparently, it was. Was it possible to be so thrilled and terrified at the same time?

“Oh, honey, I know,” Barb said soothingly. “I was scared when I found out I was pregnant with Michael, too. But you’ll get over that, I promise.”

“What if I screw this up?”

“You won’t. You and Jameso will make the most beautiful baby, and you’ll love it in a way you’ve never loved anyone in your life.”

“What if Jameso can’t handle this and he leaves?” Her husband and her father had bailed on her—why should she expect any better from Jameso?

“If he does, you’ll manage on your own. You have a lot of people to help you.”

She put her hand on her stomach, trying to imagine a life growing in there. She couldn’t do it. It was the most wonderful, impossible, surreal thing that had ever happened to her.

“Where is Jameso right now?” Barb asked.

“At work at the Dirty Sally.”

“He gets a dinner break, doesn’t he? Go tell him.”

“No, I can’t tell him at work.” The Dirty Sally Saloon was the epicenter of Eureka’s highly developed gossip chain. If Jameso really did flake out on her, she’d rather it didn’t happen in front of the whole bar crowd. “I’ll tell him tomorrow. He’s off in the morning and we’re supposed to drive up to the French Mistress to check on the new gate I had installed.” The French Mistress Mine, another inheritance from her father, had turned out to contain no gold, but it was producing respectable quantities of high-quality turquoise. Work was shutting down for the winter and Maggie had installed an iron mesh gate to keep out the curious and the careless.

“That’s kind of romantic, telling him at the place you first met.”

“That’s Jameso—Mr. Romance.”

“You don’t give him enough credit. It’s going to be all right. I promise.”

“I hope you’re right.”

“Of course I’m right. Don’t you believe me?”

“I believe you.” Maybe it was talking to Barb, or maybe it was sitting here, letting the beauty of the mountains soothe her. Such a vast landscape made her feel small, and her problems small, too, in comparison.

She said good-bye to Barb, then started the Jeep and carefully backed onto the highway. She had about eighteen hours to figure out how to tell Jameso he was going to be a father. And about that long to let the realization that the thing she’d always wanted most was finally happening—and she’d never felt more unprepared.

Fall always felt like starting over to Olivia Theriot. The first sharp morning chill in the air and the tinge of gold in the leaves made her want to buy a new sweater and sharpen a pack of number two pencils. She’d turn to a blank page in a fresh notebook and start a new chapter in her life.

One of the chief disappointments in being an adult was that fall didn’t bring new beginnings that way. No new clothes, new classes, new friends, and the chance to do things over and get it right this time. While she’d sent her thirteen-year-old son, Lucas, off to school with a new backpack and a fresh haircut, she felt more stuck than ever in a life she hadn’t planned.

“I’ve got a bad feeling about this one.”

“I feel that way so often I’ve thought of having it put on a T-shirt.” Olivia slid another beer toward the man who’d spoken, a part-time miner named Bob Prescott who was the Dirty Sally Saloon’s best customer.

“You’re too young to be so cynical.” Bob saluted her with the beer glass, then took a long sip.

Next month, she’d turn thirty. To Bob, who had to be in his seventies, that probably felt young, but most days Olivia felt she’d left youth behind long ago. Maybe it was having a kid who was already a teenager. Or having lived in at least fifteen different places since she’d left home at fifteen. Or maybe this used-up feeling was really only dismay that nothing in her life had worked out the way she’d planned. Back when she was a starry-eyed twenty-something, her dreams of happily ever after had certainly never included single motherhood, a job tending bar, and sharing a house with her mother in a town so remote it didn’t even make it onto most maps.

She pinched herself hard on the wrist. Time to snap out of it. At this rate she’d end up crying in her beer, like one of her sloppiest customers. “What do you have a bad feeling about, Bob?” she asked. In the four months she’d worked at the Dirty Sally, Bob could be counted on for at least one outrageous story or proclamation a week.

“This winter.” Bob shook his head. “It’s going to be a late one. We should have had snow by now and there’s scarcely been a flurry. Mount Winston’s practically bare and here it is into October.”

“It has been awfully dry.” The other bartender, Jameso Clark, moved down the bar to join Bob and Olivia. Tall, with dark hair and a neatly trimmed goatee, Jameso was something of a local heartthrob, though lately he seemed to have settled down with Maggie Stevens. “It’s not looking good for an early ski season.”

“You working as a ski instructor again this year?” Bob asked.

“Of course.”

“Aren’t you getting a little long in the tooth to play ski bum?” Olivia asked.

Jameso’s eyes narrowed. “I’m only two years older than you. And there are plenty of guys who are older than me, a lot older, who work as instructors or on ski patrol.”

“But it’s not like it’s a real job. Not something a man can support a family on.”

“Who said anything about a family?” Jameso’s voice rose in alarm.

She never should have brought it up. Now he was going to get all pissy on her. “Things just seem pretty serious with you and Maggie. I thought you two might get married and settle down.”

“What if we do?” Color bloomed high on his cheeks. “That doesn’t mean I can’t keep skiing. Maggie likes me fine the way I am.”

“Forget I said anything.”

“You won’t be teaching anybody to ski if we don’t get snow,” Bob said. Olivia didn’t know if he was deftly cutting off their argument or merely continuing with his current favorite topic, oblivious to what had just passed between her and Jameso. Whatever the reason, she gratefully picked up the thread.

“I can’t believe you two are moaning about the lack of snow,” she said. “Why would you even want the weather we have right now to end?” She gestured out the front window of the bar, where a cluster of aspens still held on to many of their golden leaves. The sun shone in a turquoise blue sky, the thermometer on the wall showed sixty-four degrees, and the breeze through the open window at her back was dry and crisp. Olivia, who’d lived all over before coming to this little corner of the Rockies, had never seen such glorious weather.

“The weather’s good, all right,” Bob said. “Too good. We need a good snowstorm to send all the tourists packing.”

She rolled her eyes and started emptying the contents of the bus tray into the recycling bin.

“What about you, Miss O?” Jameso asked. “Have you decided yet if you’re staying in Eureka for the winter?”

Olivia fixed him with a baleful glare.

“What?” He held up both hands in a defensive gesture. “I just asked an innocent question.”

“You’re the sixth person who’s asked me that question in the past week. I’m beginning to think people are anxious to see me gone.”

“You’ve got it all wrong.” Jameso leaned his lanky frame back against the bar and grinned in a way most women probably found charming. “Maybe we’re anxious to see you stay.”

“People say if you can survive your first winter in Eureka you’re likely to stick around for good.” Bob regarded Olivia over the rim of his beer glass. “You strike me as the kind of woman who’s got what it takes to stick it out.”

This passed for high praise from Bob, who regarded most newcomers to town with suspicion—herself and Maggie excepted. Olivia suspected his approval of her had more to do with her ability to pull a glass of beer and the fact that her mother was the town’s mayor than with her potential as a mountain woman.

“I don’t see what’s so special about winter here,” she said, going back to filling the recycling bin with the bottles from last night’s bar crowd. “The way you people talk you’d think Eureka’s the only place to ever get snow.”

“It’s not just the snow,” Jameso said, “though we get plenty of that. We measure storms in feet, not inches. But snow here in the mountains isn’t like snow in the city. Some of the roads around here don’t get plowed until spring. Avalanches can block the highway into town and cut us off from the rest of the world for days. Most of the tourists leave town, so everything’s quieter. The people who stay are the ones who really want to be here, and everybody pitches in to help everybody else.”

Olivia wrinkled her nose. “You make it sound like some sort of commune.”

“That’s community—the two are related,” Bob said. “You find out who your friends really are when your car breaks down on a winter road or you run out of firewood with two months of winter left.”

“Lucille has gas heat, and I don’t plan on exploring the hinterlands this winter,” Olivia said.

“You laugh now, but you’ll find out soon enough if you stick around,” Bob said. “Folks around here look after each other.”

“I can look after myself. Thanks all the same.” Olivia had a hard enough time getting used to everyone in town knowing everyone else’s business—knowing her business. How much worse would it be when there were fewer people to keep the busybodies occupied? She was tempted to get out of town while she still could, but her son, Lucas, liked it here, and though her mother, Lucille, would probably never admit it, Olivia thought she liked having them here in Eureka, too.

Besides, she didn’t want to give certain people the satisfaction of thinking she was running away from them.

She hefted the recycling bin onto one hip and headed out the back door, to the alley behind the bar where the truck could pick it up this afternoon.

“Let me help you with that.” Before she could react, two strong arms relieved her of her burden.

She glared up at the man whose broad shoulders practically blotted out the sun. “What are you doing here, D. J.? I thought I made it clear I didn’t want to see you again.”

A lesser man might have been knocked off his feet by the force of her glare, but Daniel James Gruber, too good-looking for her peace of mind and far too stubborn by half, never flinched. “Which do you think is heavier?” he asked. “These bottles or that grudge you’re carrying around?”

If he thought her feelings about him were the heaviest thing in her heart, he didn’t really know her very well.

But, of course, he didn’t know her. If he had, he never would have left her in the first place. So why had he tracked her all the way to middle-of-nowhere Eureka, Colorado? And why now? “Go home, D. J.,” she said. “Or go back to Iraq. Or go to hell, for all I care. Just leave me alone.”

“Mo-om!” The shout was followed almost immediately by a boy with wispy blond hair, large ears, and round, wire-rimmed glasses. He wore cutoff denim shorts, a too-large T-shirt, and the biggest smile Olivia could remember seeing on him.

“You don’t have to shout, Lucas,” she said. “I’m right here.”

“Mom, you gotta come out to the truck and see the fish I caught.”

“Where were you fishing? You know I told you not to go off in the mountains by yourself.” Almost two months ago, Lucas had fallen down a mine tunnel on one of his solo expeditions, exploring the surrounding mountains. Ever since, Olivia had been haunted by worries over all the ways this wild country had for a boy to get hurt—mine tunnels and whitewater rivers, boiling hot springs and treacherous rock trails. Lucas had never been a particularly rambunctious boy, but he was still a boy, with a boy’s disregard for danger.

“I didn’t go by myself. D. J. took me.”

She could feel D. J.’s hot gaze on her, though she didn’t dare look at him. If she detected the least bit of smugness in his expression, she’d leap up and scratch his eyes out. How dare he think he could get to her by playing best pal to her son!

But she couldn’t tell him what she thought of him now, with Lucas standing here. The boy idolized the only man who’d ever really taken an interest in him. The man she’d been so sure would make such a good father.

She bit the inside of her cheek, the pain helping to clear her head, and managed a half smile for Lucas. “Go ask Jameso to give you a soda and I’ll be out to look at your fish in a minute,” she said.

She watched him go, his shoulders less rounded than they’d been even three months ago, his head held higher. He’d shed the hunched, fearful look he’d worn when they first arrived here. That was the real reason she couldn’t leave Eureka, at least not yet. As improbable as it sounded, Lucas was thriving here, roaming the unpaved streets of town and the back roads beyond, as if he’d lived here all his life.

“He’s a great kid,” D. J. interrupted her thoughts. “I’m not hanging out with him to get to you, if that’s what you think. I like spending time with him.”

Since when had he developed this ability to know what she was thinking? Too bad he hadn’t been so tuned in before he skipped town. “You’re just prolonging the hurt,” she said. “Isn’t it enough that you broke his heart once?” That he broke her heart? “You should go now, before you make it worse.”

“There’s unfinished business between us. I won’t leave until it’s settled.”

“It’s settled, D. J. It was settled when you walked out the door six months ago.” She started to move past him, but he took hold of her arm, his touch surprisingly gentle for such a big man, familiar in the way only someone with whom you’d shared the deepest intimacy could be. No matter that they hadn’t been lovers in months, her traitorous body responded to him as if he’d last held her only yesterday, her skin heating, her heart thumping harder.

“I’m not letting you off that easy,” he said. “I’ve decided to stay. At least for the winter. Maybe if we spend a few months snowed in here together you’ll let go of that grudge long enough to grab hold of what you really need.”

“And you think you’re what I need? Of all the self-centered, arrogant, male things to say.”

“All I’m saying is, you don’t have to carry all your burdens alone. Let me help.”

She wrenched away, rushing into the bar and out the front door, past Jameso and Bob and Lucas, who sat on a stool next to Bob, sipping a soft drink from a beer mug. She wanted to jump in her truck and drive and keep driving without stopping until she was a thousand miles away from here.

But she’d already learned moving on wasn’t the answer. You couldn’t ever really run away when the thing you were running from was yourself.

“I’m a lot of things, but I’m not a magician. I can’t pull money out of thin air or make this budget stretch to cover one thing more.” Lucille Theriot, Eureka’s mayor, stood behind the front counter of Lacy’s, the junk/antique shop she owned, trying her best not to lose her temper with the older woman across from her. Cassie Wynock, town librarian and perpetual thorn in Lucille’s side, thought her family’s deep roots in the town entitled her to anything she wanted. Today, she wanted new shelves for the library, an item not in the town’s very tight budget.

“We ought to have plenty of money,” Cassie said. “The Hard Rock Days celebration this year was the biggest it’s ever been. I know for a fact the Founders’ Pageant sold out.” She patted her hair, preening. The play devoted to telling the story of the town’s origins had been written and directed by Cassie, who’d also taken a starring role.

“The extra money we took in from Hard Rock Days doesn’t begin to make up for the money we aren’t getting from the state and federal governments this year. We’ve had to really tighten our belts. I’ve already warned people not to expect plowing of side streets this winter.”

“People around here can do without plowing. They can’t do without the library.”

Lucille was trying to think of a suitable response to this bit of skewed logic, perhaps by pointing out that if the streets weren’t plowed people couldn’t get to the library, when the cow bells attached to the back of her front door jangled. She looked up, hopeful of a customer who would necessitate cutting her conversation with Cassie short. Instead, Bob Prescott shuffled in.

“Afternoon, ladies,” he said, touching the bill of his Miller Mining ball cap.

Cassie wrinkled up her nose. “You smell like a brewery.”

Bob did have a faint odor of beer about him, but this was nothing new. He spent most afternoons propping up the bar at the Dirty Sally. “Stop by the saloon any afternoon, Cassie, and I’ll buy you a drink,” Bob said. “I predict it’ll do wonders for your disposition.”

Considering Cassie’s disposition was almost always bad, Lucille doubted alcohol would help. “What can I do for you, Bob?” she asked.

“You’re interrupting a private conversation,” Cassie said before Bob could reply.

“I was explaining to Cassie how the town budget is so tight this year we’ve decided to forgo plowing side streets for the winter,” Lucille said.

“I say we set up snowmobile-only lanes and forget about plowing altogether,” Bob said. “ ’Course, you won’t have to worry about that at all if we don’t get snow.”

“And I say new library shelves are a matter of liability,” Cassie said. “The old ones are falling apart. If we don’t replace them, someone could get hurt.”

Lucille met Cassie’s defiant look with a skeptical one of her own. Were the shelves in such bad shape? Or would Cassie see to it that they did start falling apart, even if she had to remove a few bolts to do so? She looked like a prim old maid, but Lucille knew she had nerves of steel. Coupled with her outsized sense of self-importance, it could be a recipe for trouble.

“I’ll have someone come down and examine the existing shelves for safety concerns,” Lucille said. “Maybe we can reinforce them somehow.” She turned to Bob. “Can I help you, Bob? I just got a nearly complete set of 1970s-era National Geographics and two solid brass spittoons in stock if you’re interested.”

“Nah, I’m here on official business, Madam Mayor.” He propped one elbow on the counter and leaned against it, his customary posture at the Dirty Sally.

“Official business?”

“You might say it relates to your conversation with Cassie. I’ve got an idea for a fund-raiser for the town. Something to liven up the quiet weeks after the summer tourists have left and before the ski crowd shows up.”

“We don’t get a ski crowd, Bob,” Lucille said. “That’s over in Telluride. The best we can hope for is a few folks who stop on their way to and from the slopes.”

“They’re all tourists to me,” he said dismissively. “What I’m talking about is entertainment for the locals and a way to bring in a little extra cash for the town coffers.”

Lucille leaned back, arms folded. “Let’s hear it.” Bob’s past ideas—all of them voted down by the town council—had included boxcar derby races down the steep main road leading into town, hiring a burlesque troupe to “liven up” the Independence Day celebrations, and letting tourists pay to be a miner for the day and work Bob’s claims with a pickax and shovel.

“Let’s start a pool on when the first snow will fall,” he said. “Charge five dollars a guess and the person who gets closest to the date and time wins half the money. The town keeps the other half.”

“I’m certain city-sponsored gambling like that is illegal,” Cassie sniffed.

“She’s right, Bob,” Lucille said. “We can’t do something like that. It was a good idea, though.”

“Humph. Nothing to stop me from doing it, is there?”

“You can’t run a gambling operation of any kind without a license,” Lucille said.

“Tell that to the weekly poker games in the back room of the barber shop.”

Lucille covered her hands with her ears. “I didn’t hear that,” she said loudly.

The door opened again and a distinguished-looking man with tanned skin and silver hair and moustache entered. Lucille’s heartbeat sped up and she fought the urge to smooth her hair or check the front of her blouse for lint. “Hello, Gerald,” she said, aware that her voice had taken on a musical lilt.

“You’re looking lovely as usual, Lucille.” He smiled, showing perfect white teeth she suspected were caps, but who cared? Everyone was entitled to his or her little vanities.

“Who are you?” Bob demanded.

Gerald’s smile never faltered as he turned to face the old man. “I’m Gerald Pershing. Who are you?”

“I’m Bob Prescott. I live here.”

“In this store?”

Bob looked as if he’d bit down on a walnut shell. He scowled at Lucille. “He a friend of yours?”

“Mr. Pershing is visiting from Texas,” she said.

“Him and half the state, feels like.” Bob gave Gerald a last dismissive look, then stomped out.

“So nice to meet you, Mr. Pershing. I’m Cassandra Wynock, the town librarian.” Cassie extended her hand, palm down, as if she expected Gerald to kiss it. Her cheeks were pink and while she didn’t exactly flutter her eyelashes, the suggestion was there.

“Nice to meet you, too, Miss Wynock,” Gerald said. He shook the offered hand but didn’t linger over it. Lucille fought back the urge to toss Cassie out onto the sidewalk by her ear. It had been years, but she recognized jealousy tightening her stomach and lending a sour taste to her mouth—a particularly ugly and useless emotion.

“I stopped by to see if you’d be free for dinner tomorrow evening.”

Cassie’s frigid silence alerted Lucille that Gerald was speaking to her. Her cheeks heated, and she busied herself straightening the stack of newspapers on the counter, avoiding his gaze. They’d had lunch once already—not a real date, just two acquaintances running into each other at the Last Dollar Café and agreeing to share a table. But the encounter had left Lucille feeling sixteen again. Well, maybe not sixteen. Some of the ideas she had when she thought about Gerald wouldn’t have entered her head at sixteen. Maybe twenty-six, then. Old enough to know what’s what and young enough to get it.

But who said she was too old to get it—whatever “it” turned out to be? Sex? Companionship? Love? Aware of Cassie staring at her, she smiled at Gerald. “Dinner sounds wonderful.”

“About those shelves . . .” Like a Rottweiler who’d grabbed hold of Lucille’s shirttail, Cassie refused to let go.

“I’ll send someone over to the library tomorrow to take a look at the shelves,” Lucille said, glaring at her.

Cassie ignored the look, offering her schoolgirl smile once more to Gerald. “I was telling the mayor the library is in serious need of new shelving. The ones we have are a danger to the patrons.”

“That does sound serious.” He looked sympathetic, but his eyes found Lucille’s and he lowered one lid in the suggestion of a wink.

Lucille coughed. It was either that or burst out laughing, and laughing at Cassie was never a good idea. She had friends in county government who could make Lucille’s life uncomfortable. Right now, thanks to Gerald’s sympathy, Cassie looked triumphant. “You’ve got to find room in the budget to replace those shelves,” she said.

“Submit your request in writing and the town council will take it under consideration at our next meeting,” Lucille said. “But if the money isn’t there, it isn’t there.”

Cassie sniffed. “It was so nice to meet you, Mr. Pershing,” she said, transforming immediately when she faced Gerald once more. “Do stop by the library. I’d love to show you around.”

“If you’re sure I won’t be injured by falling shelves.”

“I . . . well.” Cassie sniffed again. “Well!” Then she hurried away, glaring at both of them over her shoulder just before she pushed out the door.

Lucille collapsed against the counter, laughing. “Gerald, you are too wicked,” she said.

“It is a persistent fault.” He leaned across the counter toward her, intimately close, his mouth mere inches from hers, eyes shining. She felt a thrill, the excitement of being the center of attention to the person she most wanted to be with. “You are amazing,” he said. “Running a business and taking on the responsibility of overseeing the whole town . . . I don’t see how you do it.”

“It’s not as if this business is particularly demanding. And I don’t run the town—the town council does that. I’m more of an administrator.”

“Still, it’s a large burden for one person, especially in these perilous financial times.”

Gerald had a formal, flowery way of talking that some people found off-putting, but Lucille saw it as part of his charm. He behaved like a man from an earlier, more courtly era. “The lack of money does make the job a little more stressful,” she admitted. “We don’t have enough money for essentials, much less extras like Cassie’s library shelves.”

“Much like many a personal budget, I suspect.”

“Yes, I know a lot of people are hurting, which is why I hate to cut any services residents depend on.”

He straightened, his expression more serious. “In my work I see it often.”

Gerald had told her he was involved in investments some way. “Is your business hurting, too, with the economy?” she asked, then felt stupid for even asking. Of course it was. Whose wasn’t? Even receipts at Lacy’s—the kind of place people shopped when they were strapped for cash—were down.

“On the contrary. I don’t like to brag, but I’m doing very well for my clients. I was lucky enough to discover a few investments that have actually grown, despite the economic difficulties in other sectors. In fact . . .” He paused, his eyes searching hers. She nodded, encouraging him to continue. “I would never presume to take advantage of your friendship,” he said. “But I would love to help you out of your difficulties. I could show you some areas where the town might think about investing, where you could realize a solid return on your money quite quickly. It might be enough to help you out of your current difficulties.”

The idea seemed crazy, but definitely tempting. Right now the town had its small surplus in certificates of deposit with the Eureka Bank. “I couldn’t make a decision like that on my own. The town council would have to approve.”

“Of course. And there’d be no obligation.” He smiled, blue eyes sparkling. God, he was handsome. “I’ll bring some material to dinner with me for you to look over. You can let me know and if you like, I can make a presentation to the council.”

His interest in her problems touched her. She’d been alone so long—raising her daughter with little help from Olivia’s father, coming to Eureka after Olivia left home, and making a life for herself here. She’d enjoyed living on her own terms, being independent. She scarcely knew how to lean on someone else anymore, but it was a surprisingly good feeling. As if the time was finally right for a little romance in her life.