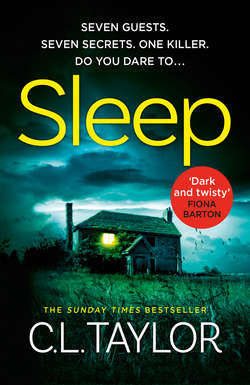

Читать книгу Sleep - C.L. Taylor, C.L. Taylor, C. L. Taylor - Страница 15

Chapter 6 Anna EIGHT WEEKS AFTER THE ACCIDENT

ОглавлениеThursday 26th April

I feel like a balloon on a string, floating above the pavement. Alex’s hand is wrapped tightly around mine but I can’t feel the pressure of his fingers on my skin. I can’t feel anything. Not the pavement under my feet, not the wind on my cheeks, not even my laboured breath in my throat. Tony, my stepdad, is walking ahead of us, his white hair waving this way and that as the wind lifts and shakes it. His black suit is too tight across his shoulders and every now and then he tugs at the hem. When he isn’t pulling at his clothes he’s glancing back at me, over his shoulder.

‘All right?’ he mouths.

I nod, even though it feels like he’s looking straight through me, talking to someone further down the street. I barely recognised the woman who stared back at me from the mirror this morning as she pulled on the white blouse, grey suit and black heels that had been laid out on the bed for her. I knew it was me in the mirror but it was like looking at a photograph of myself as a child. I could see the similarity in the eyes, the lips and the stance but there was a disconnection. Me, and not me, all at the same time. I barely slept last night. While Alex snored softly beside me, curled up and hugging a pillow, I lay on my back and stared at the dark ceiling. When I did fall asleep, sometime after three, it wasn’t for long. I woke suddenly at five, gasping, shrieking and clawing at the duvet. I’d had my hospital dream again, the one about the faceless person staring at me.

‘It’s going to be okay, sweetheart,’ Mum says now, trotting along beside me, her cheeks flushed red, the thin skin around her eyes creased with worry. When we got out of the car she took my right hand and Alex took my left. I felt like a child, about to be swung into the air but with fear in my belly rather than glee. At some point Mum must have let me go because now her hands are clenched into fists at her sides.

‘Anna.’ Mum’s gloved hand brushes the arm of my coat. ‘This isn’t about you, love. You’re not the one on trial. You’re a witness. Just tell the court what happened.’

Just the court: the judge, the jury, the lorry driver, the public, the press, and the family and friends of my colleagues. I need to stand up in front of all of those people and relive what happened eight weeks ago. If I didn’t feel so numb, I’d be terrified.

‘Anna!’

‘Over here!’

‘Anna!’

‘Mr Laing!’

‘Mr Khan!’

The noise overwhelms me before the bodies do. Everywhere I look there are people, necks craned, arms reaching in the air – some with microphones, others with cameras – and they’re all shouting. My stepdad wraps an arm around my shoulders and pulls me close.

‘Give her some space!’ He raises an arm and swipes at a camera that’s just been shoved in my face. ‘Out of the way! Just get out of the bloody way, you imbeciles.’

As Tony angles me out of the crowd I search desperately for Mum and Alex but they’re still trapped in the throng of people by the courthouse entrance.

‘Anna! Anna!’ A blonde woman in her early forties in a pink blouse and a puffy black gilet presses up against me and holds a digital Dictaphone just under my chin. ‘Are you satisfied with the verdict? A two-year sentence and two of your colleagues are dead?’

I stare at her, too shocked to speak, but she registers the turn of my head as interest and continues to question me.

‘Will you go back to work at Tornado Media? Was that your boyfriend you were with?’

‘You’re having trouble sleeping, aren’t you?’ a different voice asks.

I twist round to see who asked the question but there’s a sea of people following us down the steps – dozens of men in suits, photographers in jeans and anoraks, a dark-haired woman in a bright red jacket, an older lady with permed white hair, my mother – pink-cheeked and worried – and, on the other side of the group from her, the thin, anxious shape of my boyfriend.

The blonde to my right nudges me. ‘Anna, do you feel responsible in any way?’

‘What?’ Somehow, in the roar, Tony heard her question. Someone behind me bumps against me as my stepdad stops sharply. ‘You bloody what?’

It’s like a film, freeze-framed, the way the crowd around us suddenly falls silent and stops moving.

The blonde smiles tightly at Tony. ‘Mr Willis, is it?’

‘Mr Fielding actually, who’s asking?’

‘Anabelle Chance, Evening Standard. I was just asking your daughter if she felt in any way responsible for what happened.’

The skin on my stepdad’s neck flushes red above the white collar of his shirt. ‘Are you bloody kidding me?’ He stares around at the crowd. ‘Can she actually say that?’

‘It was just a question, Mr Fielding. Anna’ – she tries to hand me a business card – ‘if you’d ever like to chat then give me a—’

He knocks her hand away. ‘You’re treading a very fine line. Now, get out of our way, before I make you.’

Mum and Alex wrap around us like a protective shield, Alex beside me, Mum next to Tony, as we hurry away from the noise and chaos of the courtroom.

‘Have you got a tissue, love?’ Mum asks as we reach the car. ‘You’ve got mascara all down your face.’

I touch a hand to my cheeks, surprised to find that they’re wet.

‘Yes, I’ve …’ I reach a hand into my suit pocket and feel the soft squish of a packet of Kleenex. But there’s something else beside them, something hard with sharp corners, something I don’t remember putting into my pocket when I got ready this morning. It’s a postcard. The background is blue with white words forming the shape of a dagger. The words turn red as they near the point of the blade and a single drop of blood drips onto the title: The Tragedy of Macbeth.

‘What’s that?’ Mum asks as I flip the card over.

I shake my head. ‘I don’t know.’

There are two words written on the back, in large, looping letters:

For Anna

I look from Mum, to Dad and then to Alex. ‘Did one of you put this in my pocket?’

When they all shake their heads, I flip it back over and read the quote:

Methought I heard a voice cry ‘Sleep no more! Macbeth does murder sleep’ – the innocent sleep, Sleep that knits up the ravelled sleave of care, The death of each day’s life, sore labour’s bath, Balm of hurt minds, great nature’s second course, Chief nourisher in life’s feast.

I know this quote from studying Macbeth at A-level. It’s Macbeth talking to Lady Macbeth about the frightening things that have happened since he murdered King Duncan.

‘Anna?’ Alex says. ‘Are you okay? You’ve gone very pale.’

I glance back towards the courthouse and the throng of faceless people milling around.

‘Someone put this in my pocket.’

‘It wasn’t that bloody journalist, was it?’ Tony says. ‘Because I’ll get on the phone to her editor if I need to. I won’t have her harassing you like this.’

‘Let me see that.’ Alex leans over my shoulder and peers at the card. ‘Is that a quote from Shakespeare?’

‘It’s Macbeth telling Lady Macbeth about a voice he heard telling him he’ll never sleep again.’

‘Oh, that’s horrible.’ Mum runs her hands up and down her arms. ‘Who’d give you something like that?’

‘Here, give me that.’ Tony takes the card from my fingers, rips it into tiny pieces and then drops them into a drain. ‘There. Gone. Don’t give it a second thought, love.’

No one mentions it all the way home but the words rest in my brain like a weight.