Читать книгу On the Brink - Claire Bisseker - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

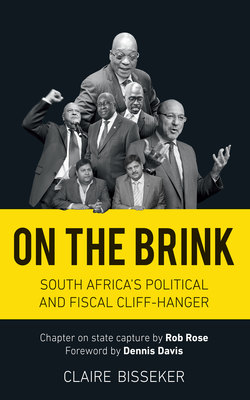

3 All the president’s friends: An analysis of state capture

ОглавлениеBy Rob Rose, Financial Mail editor

‘Corruption … has its hand at the throat of government service delivery. And it is getting tighter. It is getting tighter as the grip of state capture rips the soul out of state-owned companies, encourages gross financial mismanagement, and promotes unfettered looting.’

– Sipho Pityana1

‘If you say “state capture”, what do you mean? … We are talking about small issues, and you make them big issues. You are merely using phrases. You are using what people call, if they want to say things to the media, soundbites.’

These were the disdainful words Zuma used, speaking to a provincial meeting of the ANC in Irene in May 2016.2 It was a moment rich in irony. After all, it was Zuma’s friendship with a family of immigrants, the Gupta family, who had arrived in South Africa in the 1990s from India, which had led to the phrase ‘state capture’ becoming part of the local lexicon.

Atul Gupta – the middle of three brothers, sandwiched between the eldest, Ajay, and the youngest, Rajesh (also known as Tony) – came to South Africa in 1993 on his father’s orders, ostensibly because he believed that ‘Africa would become the America of the world’. Ajay, the master tactician of the family, followed Atul in 1995, and Rajesh joined them in 1997.3

The family started small, hardly foreshadowing the immense hold they would eventually gain over the South African economy. They opened a shop selling shoes imported from India in Johannesburg’s swanky Killarney Mall, and then a business called Correct Marketing, which imported and sold computers.

That business would be renamed Sahara Computers (after their home town, Saharanpur), and although its revenues were only R1,4 million in 1994, its fortunes would change dramatically once the family got a foot in the door of government.

The Guptas assiduously courted politicians (the first was said to have been Thabo Mbeki’s trusted confidant, Essop Pahad) and, soon, Sahara was rolling in government contracts. By 2016, Sahara was clocking up R1,1 billion in annual revenues. But it was the family’s meeting with Zuma, then deputy president to Mbeki, that would later provide them with a gilded invitation to the R500 billion in government contracts that are divvied out each year, largely to the private sector.

Atul Gupta said he first met Zuma in 2002, ‘when he was the guest at one of Sahara’s annual functions’.4 From there, it all became rather cosy. By 2005, Zuma’s then 24-year-old son, Duduzane, began working at Sahara and soon after, his company, Mabengela, ended up as ‘investors’ in the Gupta network of firms. The relationship provided invaluable political cover for the Gupta family, with Duduzane becoming the proxy for the Guptas’ investment in the presidency.

When the Gupta family’s investment vehicle, Oakbay Resources, bought the Shiva uranium mine for R270 million in 2010 (thanks to a R250-million loan from the state-owned Industrial Development Corporation), Mabengela snapped up an effective 11,9% of Shiva. The Mail & Guardian went so far as to say Mabengela ‘appears to be the vehicle for the Zuma family’s empowerment by the Gupta family’.5

What is indisputable is that the Gupta family has made the Zumas fabulously wealthy. At last count, Duduzane Zuma’s effective stake in Oakbay Resources, the company listed on South Africa’s JSE Securities Exchange that incorporates Shiva, was worth about R1 billion.6

It was a mutually beneficial relationship and the Guptas’ timing was impeccable. Once Zuma was elected as president in 2009, he set about repositioning the state to make it the driving force of the economy, ostensibly using government budgets to benefit black-owned companies. The biggest tool in his arsenal was the SOE sector. Of these, the two largest spenders were the rail utility, Transnet, and electricity company, Eskom. With a purse of more than R200 billion a year across 13 entities, the SOE sector had a free hand to dish out large contracts, provided they had board approval.

By contrast, any direct tender from government would be subject to parliamentary oversight, a cumbersome process. So the SOEs began ladling out generous helpings of tenders, for just about everything. Some have dubbed this the ‘near-complete outsourcing of government’s core functions’; the Public Affairs Research Institute called it the ‘contract state’.7 Either way, for those firms that had nurtured political connections, the SOE sector became a cash cow.

Zuma, speaking in Irene to his ANC comrades that autumn morning, rubbished the notion that state assets had been diverted to assist any single private-sector interest. ‘I know politicians love it,’ he told the appreciative crowd, then continued in a mocking tone meant to mimic his critics: ‘The state capture, the state capture. But what does it mean? What is the state?’

It’s not an especially difficult question to answer. At its heart, it means an illicit and wide-ranging system in which certain private-sector players have gained the ability to influence the government – including cabinet ministers, SOEs and public officials – for their private benefit. If corruption is simply bending the rules of the system, state capture is redefining that system and its rules entirely.

For example, if a CEO bribes a politician to pass a new law that gives his company a permanent privileged position in the market, that would amount to state capture. In this way, resources meant for the public benefit are diverted to serve private interests – rent-seekers, essentially.

‘State capture can be extremely pernicious to an economy and society, because it can fundamentally and permanently distort the rules of the game in favour of a few privileged insiders’ – this according to a World Bank publication, Anticorruption in Transition.8

The practice is far more audacious than vanilla corruption. In 2017 a group of academics released the Betrayal of Promise Report, in which they argued that state capture is far more than simply a way of amassing wealth: ‘Institutions are captured for a purpose beyond looting. They are repurposed for looting as well as for consolidating political power to ensure longer-term survival, the maintenance of a political coalition, and its validation by an ideology that masks private enrichment by reference to public benefit.’9

A novel spin on an old idea

Zuma might claim the term ‘state capture’ has no meaning or that there is no evidence that the state had been captured. Even though there was no hard evidence at that stage that Zuma had personally ordered that contracts be given to the Guptas, the circumstantial evidence was immense. Soon, the Guptas were hosting cabinet ministers at their Saxonwold estate, making offers of political office they would never have dared make without Zuma’s tacit agreement.

As these details emerged, critics accused Zuma of not simply being captured, but of being metaphorically ‘owned’ by the Guptas. Memorably, Julius Malema coined the term ‘Zuptas’ to illustrate his point that the motives of Zuma and the Gupta family were indivisible.10

Mmusi Maimane said, ‘Zuma is controlled by the Guptas. Once you have a weak institution like the ANC and a government that is institutionally captured, you only have to win control over a few individuals like Jacob Zuma and you control everything.’11

David Lewis, who heads Corruption Watch, says that what distinguishes South Africa’s situation from other instances of state capture around the world is that, here, the country’s president plays a central role.12 ‘In other countries, there have been cases of institutions becoming heavily subordinated to one lobby or another. But it’s extraordinary for one family to have such a hold over a head of state. And this has cascaded down, to the South African Revenue Service, companies like Eskom and others,’ says Lewis.

Lewis says the ’capture of the state’ happens so rapidly precisely because of Zuma’s unfettered ability to appoint ministers, and the head of bodies like the revenue service and state-owned companies.

So, despite what Zuma told the ANC congress in Irene that day, for a businessman to be shopping around cabinet positions, with all the discretion of a drunk at a poker game, suggested that the executive had indeed been captured. One needed to look no further than Eskom and Transnet, where evidence was rapidly stacking up of the extent to which they had been compromised by the Guptas.

Foremost is the case of Eskom. With revenues of a staggering R163 billion, Eskom is one of the 20 largest companies in Africa. It produces 95% of South Africa’s electricity but its reach is far wider – nearly one in two people on the African continent rely on Eskom for power. So what happens at Eskom matters plenty. A study by Quantec Research found that approximately 7,4% of South Africa’s GDP can be traced back to the direct, indirect and induced impacts of Eskom.13 In fact, more than 516 000 South Africans – nearly 1% of the country’s population – rely on Eskom for income, including those employed directly and indirectly, and their family members.14

In 2016, 1 656 companies sold services and products to Eskom, for which taxpayers paid almost R170 billion. (This is equivalent to what it costs the country to repay interest on its government bonds every year.)15 Given that Eskom’s mandate from Zuma was to use procurement to empower smaller black-owned firms, its deep pockets were of considerable interest to the Gupta family. And considering that 30c of every R1 Eskom spends is on coal, the most obvious route in was to buy a coal mine.

As luck would have it, Glencore, a global commodities trading giant based in Switzerland, and headed by South African Ivan Glasenberg, had a mine it was looking to sell – Optimum Coal. Optimum even had a supply contract in place with Eskom, dating back to 1993. Only, by 2015 it had become severely loss-making for Glencore in a world where coal prices were falling and labour costs were soaring.

Not only was Eskom, under its new boss Brian Molefe (more on him later), unwilling to negotiate higher rates, it slapped a R2,5-billion ‘fine’ on Optimum for providing low-quality coal. With this liability hanging over its head, Optimum was essentially bankrupt. In August 2015, Optimum was placed in business rescue. Still, a few potential bidders popped up, most notably a company called Pembani, controlled by billionaire Phuthuma Nhleko, former chief executive of MTN. But Eskom vetoed Pembani. Eskom vetoed everyone, except for the Guptas.

The dark heart of state capture

The story of how the Guptas got their hands on Optimum is perhaps the single most illustrative example of the dark heart of state capture.

In December 2015, Tony Gupta and one of the family’s business partners, Salim Essa, flew to Switzerland to meet Glasenberg in Zurich. Their aim: to convince him to sell Optimum. On this trip, curiously, the family would have high-level help. The Gupta delegation was accompanied by no less a person than Mosebenzi Zwane, South Africa’s freshly minted mining minister.

At that stage, Zwane was less than three months into the job, but he’d already been linked to the Guptas. The red flags included his surprisingly rapid elevation from being a teacher to head up agriculture and tourism in the Free State and then to lead one of the country’s most mission-critical industries, mining.

When the Guptas held a private wedding in South Africa and wanted to use the Waterkloof Airbase for the convenience of their guests, they got Zwane to write a letter inviting their family to South Africa under the pretext that they were visiting for government-related purposes, according to Malema. Zwane’s presence on that trip to Switzerland, alongside the Gupta negotiating team, to wrangle with Glasenberg over the sale of Optimum, was no less brazen.

It also seemed to flout Parliament’s ethics code, which states that members must ‘avoid placing themselves under any financial or other obligation to any outside individual or organisation where this creates a conflict or potential conflict of interest with his or her role.’16 Later, after his trip was exposed, Zwane argued that he’d done nothing wrong.

‘Let me put the record straight: I met with [the Guptas], I’ve engaged them, I’ve engaged other big mining giants and will continue to do so in future,’ said Zwane. ‘One of my responsibilities is to attract investment in the country and you can’t attract investment in the country if you’re not talking to people like the Guptas.’17

But the penny was beginning to drop, at least in the public mind. As a result, the Guptas were fast becoming public enemy number one. By February 2016, Absa Bank had already terminated their bank accounts, and the other three big banks in South Africa were soon to follow suit.

Funding was becoming a problem for the Guptas. After all, shaking hands with Glasenberg was only half the battle; finding the R2,1 billion to actually pay for Optimum Coal was the real trick. If the banks weren’t going to lend this money to the family to buy the ailing coal mine, they needed to come up with another plan. Luckily, the Indian state-owned bank, Bank of Baroda, was willing to lend them the first R1,5 billion – but that still left them around R600 million short.

The way in which the Guptas got this final tranche of cash was audacious, to say the least. The details emerged in a complaint submitted to the Hawks, under Section 34 of the Corruption Act, by Optimum coal’s business-rescue practitioner, Piers Marsden. In it, Marsden sketches out the bizarre events of Monday 11 April – the day before the Guptas had to pay the final instalment.

It went like this:

10 am:Nazeem Howa, who was CEO of the Gupta’s investment vehicle, Oakbay, meets Marsden and tells him that Tegeta is ‘R600 million short’. He asks Marsden to approach the banks – FirstRand, Investec and Nedbank – for a R600-million ‘bridging loan’.

1.30 pm:Marsden races to meet the consortium of banks at FirstRand’s office in Sandton to ask them to lend the money to Oakbay. But the banks refuse.

3 pm:Marsden phones Howa to tell him this.

9 pm:Eskom’s board holds a special meeting at which the board, headed by Ben Ngubane, agrees to make a R586 million pre-payment to Optimum for the future supply of coal.

Not only was this an exceedingly strange thing for a country’s electricity utility to do, but the pre-payment was not made to Optimum but to another of the Guptas’ companies, Tegeta. This meant that Marsden, as the business-rescue practitioner running Optimum, never saw Eskom’s R586 million.

At the time, Tegeta didn’t even own Optimum nor did it have a stitch of coal. It was just a cash shell with little more than the right to buy a coal mine. In other words, the money didn’t go to buy coal, it went elsewhere – to help the Guptas buy a mine.

How Brian Molefe threw away a brilliant career

So, how did Eskom end up bending over backwards to help the family? The answer is that, by this stage, the Guptas had enough friends in high places to ensure they could get what they wanted – even R600 million at short notice from a state company that has no place pretending to be a bank.

At Eskom, the CEO at the time was a smart technocrat named Brian Molefe. A fast-talking, charismatic dealmaker, Molefe had been singled out by Nelson Mandela shortly after the democratic election in 1994 as someone with a bright future. Mandela had decreed that while the older struggle veterans could take their places in Parliament after that historic election, ‘the younger ones must go to school’. So Molefe, along with a number of other promising young party cadres, including Lesetja Kganyago (now the governor of the Reserve Bank), were sent to study economics in London.18

After Molefe had returned to South Africa, he was summoned by the then finance minister, Trevor Manuel, to become a director of assets and liabilities at the Treasury. His star shone even brighter when he was appointed CEO of the Public Investment Corporation, a state-owned fund manager that manages more than R1,8 trillion in pensions of government employees. After a spell in the wilderness (penance, some say, for the Public Investment Corporation’s habit of financing deals for those close to Zuma’s nemesis, Mbeki), Molefe returned as CEO of Transnet. Some sources say the Gupta family were instrumental in rehabilitating Molefe, after which he seemed to be back in Zuma’s good graces.19

This is given further credence by the curious fact that the Gupta-owned New Age newspaper reported in December 2010 that it had on good authority that Molefe would be appointed to head Transnet. Yet the advert for the position was placed only the following month. And it was only two months later, in mid-February, that Molefe’s appointment as CEO was announced.

Once Molefe was in charge, strange deals began happening. In early 2014 a consortium linked to the Guptas, China South Rail, secured a slice of a lucrative R50-billion contract to provide Transnet with 1 064 trains. The Guptas, it was subsequently reported, scored R5,3 billion in kickbacks on this deal alone.20

At the time, the National Union of Mineworkers of South Africa complained to the Public Protector about ‘the implementation of opaque and underhand business dealings to line the pockets of a selected minority business and political elite’.21 But in government circles, Molefe was being praised, helped by the fact that Transnet’s profits seemed to be soaring.

Conversely, Eskom was foundering, unable to prevent a series of rolling blackouts (euphemistically dubbed ‘load-shedding’) that were hammering the economy. And it was chaos in the executive suites at Megawatt Park, as stand-in CEO Tshediso Matona was suspended, along with three executives. For what has never been quite clear. Insiders referred to Eskom as ‘Hollywood’ because there were so many people in acting positions.

So, Molefe, Mr Fix-It, was seconded to Eskom. Smart, and with a disarming ability to get employees on his side, it was, at least initially, a thumping success. Known to his staff as ‘Papa Action’, Molefe was soon being praised as the man who ‘ended load-shedding’. That is more myth than reality, as the truth was that electricity demand had plunged as economic growth came to a shuddering halt. But what is indisputable is that Eskom became far more professional and less chaotic under Molefe.

But, soon, awkward questions began to crop up about the extent to which Eskom seemed to be helping the Guptas. At first, Molefe batted them away, saying that wealthy individuals like the Ruperts and Oppenheimers also had ‘influence’. ‘The fact that they are wealthy and have influence doesn’t mean they have captured me. Influence is not capture. When I said they have influence, I don’t mean over me, I mean influence in general,’ he said during an interview on eNCA.22

Molefe claimed there was nothing unusual in the coal contracts given to the Gupta family, repeatedly arguing that the family was treated as any other.

Perhaps his version would have been allowed to stand were it not for Thuli Madonsela, a fiercely independent, 54-year-old lawyer, who had been born to a domestic worker and informal trader in Soweto. A devout ANC member, the unassuming Madonsela had been part of the team that drew up South Africa’s post-democracy Constitution.23 Perhaps mistaking her membership of the ANC for fealty, Zuma appointed Madonsela as the Public Protector for a seven-year term in 2009. This Chapter Nine institution is required to act as an ombudsman and investigate any misconduct in government. It was a move Zuma must have regretted every day since.

Madonsela, painstakingly deliberate and scrupulously fair, had become a cause célèbre for a series of blistering findings that had held powerful politicians to account – including Zuma himself, who was hauled over the coals for using state money to upgrade his home in Nkandla. It made her distinctly unpopular; ANC officials publicly lambasted her. Zuma cronies contorted themselves into knots arguing why her rulings shouldn’t apply.

But she stood firm in a stance that later led Chief Justice Mogoeng Mogoeng to describe her as ‘the embodiment of a Biblical David’.24

It was a tension Madonsela felt acutely. ‘The struggles my office often faces have nothing to do with race or gender … surprisingly, it has never been about this younger woman calling out faults, but rather the “code of the mafia” that is problematic. We are breaking that unspoken rule of taking on “one of us”. That is just not how my team and I work. If you are in the wrong, even if your intentions were good, we are not going to turn our backs,’ she said.25

And, for the office of the Public Protector, the stakes didn’t get any higher than probing state capture. In March 2016, after Jonas reported that he had been ‘offered’ the position of finance minister by the Guptas, Madonsela received three requests to investigate state capture. It was a mammoth task.

Molefe, however, didn’t seem overly worried. Speaking to the Financial Mail the day before Madonsela’s ruling came out, he said, ‘We gave her all the documents she asked for. We explained this (pre-payment) wasn’t unusual, that we’d done it before, and there was nothing wrong with it. We didn’t make the payment so that the Guptas could pay Glencore. It was about the supply of coal.’26

Asked why it happened at a late-night board meeting, seemingly designed to help the Guptas in their hour of need, Molefe said that if the coal hadn’t been delivered, then there might have been cause for worry. ‘But it was delivered, and it addressed a real coal-supply problem we had.’

The next day, Madonsela released her eviscerating 355-page State of Capture report. Molefe’s world caved in. She described the ‘prepayments’ to Tegeta as possibly illegal, warning that Tegeta’s own conduct ‘could amount to fraud’. Her bottom line: ‘It appears that the conduct of the Eskom board was solely to the benefit of Tegeta in awarding contracts to them and, in doing so, [Eskom] funded the purchase of Optimum Coal Holdings.’27

And she crucified Molefe, who, she said, ‘did not declare his relationship with the Gupta family’. Not only had Ajay Gupta described Molefe as a ‘very good friend’, phone records showed that between August 2015 and March 2016 the two had spoken 58 times. In the space of four months, Molefe had visited Saxonwold (the suburb where the Guptas live) 19 times.

Madonsela also flayed Zwane, saying his trip to Switzerland flouted the Executive Members’ Ethics Act: ‘It is potentially unlawful for [Zwane] to use his official position of authority to unfairly and unduly influence a contract for a friend or, in this instance, his boss’s son at the expense of the state.’

Madonsela’s credibility – which had continued to rise over her seven-year tenure because of her iron-clad rulings – meant the release of her State of Capture report was like a bomb going off. Opposition parties demanded resignations; marches were planned; compromised boards of SOEs spent days locked in committee.

Two days later, Molefe had to present Eskom’s financial results at Megawatt Park, where he faced a phalanx of reporters whose sole interest was his response to Madonsela’s report rather than Eskom’s accounts. Famously, in the most iconic image of the saga, Molefe broke down in tears, overwrought, apparently, by the injustice of it all. ‘The Public Protector says my cellphone reflects that I was in Saxonwold 14 times, in the area of Saxonwold … There is a shebeen there. I think it is two streets away from the Gupta house. Now I will not admit or deny that I was going to the shebeen,’ he said.28

Eskom’s chairman, Ben Ngubane, a veteran politician of questionable efficacy, squarely blamed Madonsela: ‘Thuli Madonsela has struck a death blow against Eskom and against the people of South Africa. If we lose Brian, she will take the blame,’ he said.29

It was a hapless response from Eskom’s top brass, one that was easily lampooned by the public. The ‘Saxonwold Shebeen’, assumed to be fictional, sparked a series of internet-based images that were widely circulated. Then, a few days later, in an unexpected boon for governance at Eskom, Molefe announced he would resign.30 While he argued that Madonsela had made only ‘observations’, which were either based on ‘part-facts or simply unfounded’ in an incomplete report, he was leaving, he said, to ensure no further harm was done to Eskom.31

Few had sympathy with him. Sipho Pityana, a former senior member of the ANC who had turned to campaigning for Zuma’s removal, wrote an open letter to Molefe, saying he had thrown away ‘an excellent track record as a young black professional … for a place at the high table of the forces of state capture’.32

So, you can imagine the country’s surprise when Eskom announced on 12 May 2017 that Molefe would be returning as CEO. It sparked widespread outrage – even from within Molefe’s own coterie. The ANC described his reappointment as an ‘unfortunate and reckless’ decision by the Eskom board, given that nothing had changed since he’d quit. The decision was also ‘tone deaf to the South African public’s absolute exasperation and anger at what seems to be government’s lacklustre and lackadaisical approach to dealing decisively with corruption – perceived or real’.33

David Lewis summed up the public mood by describing Molefe’s return as ‘preposterous’. ‘The sort of ethical challenges displayed by Molefe, Ngubane and the Eskom board disqualify them from public life and we will do all within our power to ensure that they are driven out of Eskom and all other public institutions,’ he said.34

Finally, on 2 June, Eskom ‘rescinded’ its decision to reappoint Molefe, ending his 19-day stint back as CEO. Molefe was out in the cold for the second time in six months – and this time, it hadn’t been his choice to leave.35

If this was a victory against state capture, rather than a calculated decision by its orchestrators to sacrifice a pawn who had become too radioactive, the credit must lie with those within civil society and the ANC who had finally drawn a line in the sand.

Backlash from investors

Futuregrowth, a Cape Town-based investment house that manages R170 billion in pension-fund money, is one of South Africa’s most socially conscious investment companies. Nearly half its money is invested in socially beneficial projects, including low-income housing and electrification projects.

In August 2016, Futuregrowth’s chief investment officer, Andrew Canter, was sitting with three funding proposals worth a combined R1,8 billion from SOEs on his desk. Canter is nobody’s fool. An American who first arrived in South Africa in 1990, he distinguished himself from many of his countrymen by immediately grasping the need for true black empowerment. But as a man of high principle, the daily revelations of state capture were beginning to wear him down.

Considering those funding proposals, Canter realised he didn’t have the information he needed to make rational investment decisions. ‘We’re worried now, in the world of politics, whether there’s political interference in lending decisions where money gets lent to politically connected persons or just to projects supported by politically connected persons,’ he said.36

So, Futuregrowth did something none of its peers had dared to do. It publicly announced that it would refuse to lend to six SOEs until it got answers: Eskom, Transnet, roads’ agency Sanral, the Land Bank, the Industrial Development Corporation and the Development Bank of Southern Africa.

It was a sensible and wholly defensible decision. As the trustee of other people’s pensions, Futuregrowth was obliged to consider whether backing state companies was still responsible.

But Canter wasn’t prepared for the furious backlash his actions would unleash. On websites and in media owned by the Guptas, Futuregrowth was cast as ‘anti-transformation’ and a stooge of ‘white capital’. ANN7, the Guptas’ television channel, argued that Futuregrowth had taken ‘a decision to effect regime change’. Molefe described Canter as an ‘idiotic imbecile from the lunatic fringe’.37

Lynne Brown, the Minister of Public Enterprises, privately lent on Old Mutual, the large asset manager that owns Futuregrowth, to ‘bring Canter into line’, according to one person with knowledge of the event. Old Mutual, which managed a large chunk of government pensions, seemed to freeze in the spotlight. For a 171-year-old South African company with an intensely proud history, theirs was a depressing response. It had the perfect opportunity to demonstrate its civic responsibility – only it fluffed its lines. Canter’s decision was ‘regrettable’ and ‘unfortunate’, it said.38

The Financial Mail decried Old Mutual as ‘gutless’ – a description that rubbed the head of the company in South Africa, Dave Macready, up the wrong way. ‘I don’t believe we took a gutless approach at all when it comes to Futuregrowth,’ he said. ‘We just don’t believe making a public statement in the media is the appropriate forum.’39

But given that the country’s economy was being hijacked, standing up to state capture publicly was exactly what the situation demanded from business. With Gordhan fighting for his political life and the sanctity of the National Treasury hanging by a thread, there could hardly have been a better time for business to stick its neck out. But it would take a few more weeks before business stood up as one and railed back against the state, loudly and publicly (see Chapter 7).

Canter’s bold move galvanised other money managers to follow suit. Abax Investments, which manages R80 billion, did the same. Its CEO, Anthony Sedgwick, said his clients’ portfolios ‘already reflect limited exposure to SOE debt due to the concerns raised publicly by Futuregrowth and a few more of our own’.40

In May 2017, the 800-pound gorilla of South African money managers, Coronation, also scaled back its bond holdings. ‘South African government bonds look cheap on the surface, but there is an insufficient margin of safety to justify holding them,’ said Coronation’s head of fixed-interest investments, Nishan Maharaj.41 While the language suggested that the decision was being made for technical reasons, many saw it for what it was: an act of legal civil disobedience from the private sector in protest against the crumbling governance of state firms.

Magda Wierzycka, CEO of investment company Sygnia, said that in 22 years in the investment industry, she’d never seen an asset manager take such a bold step. ‘More asset managers should follow their example. Debt instruments issued by SOEs should be shunned until such time as the boards of directors are replaced by ones that can uphold good corporate governance,’ Wierzycka said.42

Ultimately, history was kinder to Canter than Molefe. While Canter has been vindicated, Molefe’s fall remains a potent example of how an excellent public servant can be felled by poor judgement.

The economic harm of state capture

South Africa isn’t the only country to have been hurt by incidents of state capture, nor is this the country’s first brush with the practice. During apartheid, specific Afrikaner lobbies managed to ‘capture’ the policies of the ruling National Party, which led to an abuse of public funds for individual gain.

However, Hennie van Vuuren, director of NGO Open Secrets and author of the book Apartheid, Guns and Money, says comparisons between the apartheid era and the modern era are often misguided: ‘It’s very difficult to compare these two systems. They should rather be seen as a continuum. Certainly, you can say there was a privatisation of state assets during the late-apartheid period. For example, some of the correspondence around the awarding of the pay-TV licences to Naspers had every shade of what we’re seeing today. But the scale and circumstances are different.’43

Roger Southall, a research fellow at the Human Sciences Research Council, wrote in 2006 how the National Party ‘had used the state-owned enterprises to promote the welfare and upward mobility of Afrikaners’.44 The establishment of Eskom in 1924, as well as the Iron and Steel Corporation (Iscor), which would later be privatised and bought by Indian billionaire Lakshmi Mittal, was designed to ‘promote the development of Afrikaner capital and provide employment for … Afrikaners’.45

Lewis agrees that the corruption and diversion of assets under apartheid was more blunt. ‘That was a wider corruption, where 40 million South Africans paid for the private gains of 6 million people.’ But he feels that in the democratic era, in which institutionalised rent-seeking of this sort had supposedly been dismantled, there should have been no room for private individuals to capture the state, let alone to such a degree. ‘It’s on a scale greater than mere corruption, where a bribe is paid to get a specific contract. Here, specific groups are pre-emptively dictating decisions that should be made, so it’s far wider and more insidious.’46

There is a definite economic cost to state capture, Lewis argues: ‘If the interests of the capturer are predicated on government introducing nuclear power, because he might have a uranium mine, and that ends up influencing policy when it comes to a country’s energy mix, well, then, yes, you can measure that in rands and cents.’47

To take just one tangible example, Eskom ended up lavishing large amounts on the Gupta family for coal that it could conceivably have bought for less.

As part of the late-night meeting held to approve the controversial ‘pre-payment’ to the Guptas, Eskom agreed to pay R19,69 per gigajoule to Tegeta for coal. But this was nearly double the average price of R11,04 that Eskom was paying for coal at the time. Had a more arms-length agreement been tabled, it is conceivable that Eskom could have driven a harder bargain, ultimately leading to lower energy costs for society as a whole.

Eskom’s inefficiency and cost overruns brought load-shedding, excessive tariff hikes and supply constraints, which have significantly retarded growth and investment. There are few worse things the country could have done to damage its own economic potential than failing to prevent a shortage of electricity.

Seen through the prism of economics, state capture has the same corrosive influence as regulatory capture, in which powerful corporate interests compromise industry regulators. But if it happens frequently, in many places across the world, is it really such a big deal when it happens in South Africa?

A World Bank study on state capture, ‘Anticorruption in Transition’, points out that in countries with high levels of administrative corruption and state capture, gross domestic investment is over 20% less on average than in countries where this incidence is lower.48 Although this highlights a correlation, rather than causation, the figures are still compelling.

Predictably, for those companies that are able to ‘buy’ officials and game the system to their advantage, state capture is highly lucrative. Wider competition is undermined, while markets are restricted to those powerful individuals that have convinced policymakers to draft rules that entrench their advantage. In countries with high incidence of state capture, firms engaging in capture grew by more than 30% over three years, compared to a growth rate of only 8% among other firms, according to the same World Bank study. But for the wider public, it’s a disaster.

‘Corruption is empirically associated with lower economic growth rates, weakening the main factor that can pull people out of poverty,’ the study found. And, crucially for South Africa, one of the most unequal countries in the world, it also found that ‘income inequality has expanded most in countries with high levels of corruption and capture’.

In this context, it is doubly tragic that in order to muddy the waters, Zuma and his allies sought to reframe criticism of state capture as something invented by ‘white monopoly capital’ to prevent the economy from being transformed. In this world view, ‘radical economic transformation’ was the solution to achieving greater equality. Politically, it’s a populist message that plays well, even if the facts are a little more complicated.49

But, increasingly, society has begun to see through Zuma’s tactic of reframing his own personal travails as part of a wider social problem. In May 2017, 54% of ANC supporters agreed that Zuma should resign, according to a poll of 3 598 South Africans.50 The country is cottoning on to the fact that Zuma’s ambition isn’t to transform the economy to benefit wider society; it is all about enriching his own network.

Many in Zuma’s party who were once loyal to him are now fed up. Pityana, a former official in Mandela’s administration and an ANC member, is one such person. He now leads the Save South Africa campaign.

In his response to Zuma’s state-of-the-nation address in February 2017, Pityana urged the country to examine the real reasons why the Zuma administration had been such a complete failure. ‘We need to understand why there is no money to improve schooling and higher education. We need to understand why there is no money to provide better health care, and pay decent salaries to the people who teach our children, protect our neighbourhoods, and care for us when we are sick,’ he said. ‘The answer is often, albeit not always, a simple one: corruption.’51

But it wasn’t just the economic impact of corruption that was of such concern. Pityana warned also about the unseen rupture it was causing in the fabric of South African society. ‘State capture is the biggest source of mistrust between government and the people,’ he argued. And, like many, he had reached the conclusion that trust could be restored only ‘by opening the closet of secrecy’.52

In June 2017 that closet of secrecy was sprung open when the Gupta email cache hit the press. Though Zuma remains seemingly impervious to the revelations emerging daily, the careers of Molefe and Ngubane are over. It may not be long before the whole house of cards comes tumbling down. Repairing the trust between society and the state, and fixing the damage to the economy, could, however, take decades.