Читать книгу Fanny Burney: A biography - Claire Harman, Claire Harman - Страница 10

3 Female Caution

ОглавлениеIn 1768, the year when Fanny began to write her diary, Hetty Burney and Maria Allen, aged nineteen and seventeen respectively, were making their entrances into the world. Fanny observed their progress with profound interest and a degree of ironic detachment. Both the older girls had plenty of admirers and indulged to the full the drama of playing them off against each other. Subsequent to every evening out there would be a trail of young men calling at Poland Street, some dull, some rakish, some unsure which girl to court, some, like Hetty’s admirer Mr Seton, happy to talk to Fanny in her sister’s absence, and to discover, as the chosen few did, how well the sixteen-year-old could keep up a conversation:

[Mr Seton]: I vow, if I had gone into almost any other House, & talk’d at this rate to a young lady, she would have been sound a sleep by this Time; Or at least, she would have amused me with gaping & yawning, all the time, & certainly, she would not have understood a word I had utter’d.

F. ‘And so, this is your opinion of our sex? –’

Mr S. ‘Ay; – & of mine too.’1

‘I scarse wish for any thing so truly, really & greatly, as to be in love’, Fanny confessed to patient ‘Nobody’, but she didn’t relish being the object of someone else’s adoration. A ‘mutual tendresse’ would be too much to ask for – ‘I carry not my wish so far’.2

Fanny was just reaching the age at which she was allowed to accompany the older girls to assemblies and dances, some of which went on all night. They would set off in the family coach and straggle home in hired sedan chairs at seven or eight in the morning. There were seldom any chaperones (sometimes because the girls had deceived their father into thinking there was no necessity for one, and he was too negligent to check). Fanny made her first serious conquest – a youth called Tomkin whom she didn’t want – at the most sophisticated and risqué of the entertainments on offer to young women at the time, a masquerade. Masquerade balls were notorious as places of assignation, and excited widespread disapproval. Henry Fielding’s brother, the famous magistrate Sir John Fielding, had been trying for years to close down the establishment run by Mrs Corneley, an ex-lover of Casanova. Contemporary engravings of her parties in Soho Square show some bizarre characters, including a man leading a live bear and a person dressed as (or rather, in) a coffin, with his feet protruding from the bottom and eyeholes cut in the lid. There is also a masquerader in the character of Adam, naked except for a shrubbery loincloth, which recalls the scandalous costume of Miss Chudleigh at the Venetian Ambassador’s masquerade, who went as ‘Iphigenia’, wearing nothing but a piece of gauze.3

Fanny Burney had nothing quite so challenging to deal with at Mr Lalauze’s masquerade in Leicester Square: there was a nun, a witch (who turned out to be a man), a Punch, an Indian Queen, several Dominoes and the predictable flock of shepherdesses. The Burney girls had spent the whole day dressing, Hetty in a Savoyard costume, complete with hurdy-gurdy, and Fanny (much less adventurously) in ‘meer fancy Dress’, a highly-decorated pink Persian gown with a rather badly home-made mask. Despite its flimsiness, the mask gave Fanny ‘a courage I never before had in the presence of strangers’4 and, as with Mr Seton, she ‘did not spare’ the company. According to the procedure at masquerades, everyone was obliged to support their character, passing from one person to another asking, ‘Do you know me? Who are you?’5 until partners had been chosen and the dramatic (or not) moment of unmasking arrived. Fanny’s partner was a ‘Dutchman’ (Mr Tomkin) who had spent the evening grunting at her and using sign language. ‘Nothing could be more droll than the first Dance we had after unmasking’, she told Nobody later:

to see the pleasure which appeared in some Countenances, & the disappointment pictured in others made the most singular contrast imaginable, & to see the Old turned Young, & the Young Old, – in short every Face appeared diferent [sic] from what we expected.6

The confusion of expectations and the burlesque aspects of the masquerade appealed strongly to Fanny’s imagination, and her use of masquerade in her second novel, Cecilia, shows how well she appreciated its symbolic potential. In the novel, the heroine is tormented by her frustrated admirer Monckton, who is indulging his fantasies by dressing as a demon with a red ‘wand’. She is forcibly detained by this supposed guardian, who never speaks, but uses his devilish character to intimidate the whole company. Cecilia describes this anarchic evening as one ‘from which she had received much pleasure’, and which ‘excited at once her curiosity and amazement’.7 The abdication of identity in the masquerade is seen as both exciting and dangerous.

Fanny Burney had a much less sheltered upbringing than most middle-class girls of her time, and the constant stream of musicians, writers, singers, actors and travellers that passed through the Burney household provided endless matter for amazement and speculation. It was a peculiarly worldly atmosphere for an unworldly, innocent-minded girl to observe, and she found it attractive without always being able to identify quite why. As a novelist, she developed a taste for drama and high colouring which some critics have seen as almost an obsession with the violence potential in genteel life.8 The heroines of Burney novels are beyond reproach morally, but are constantly exposed to bizarre and outlandish events that the author is not afraid to depict as stimulating. This indicates a relish for experience which the novel form allowed Fanny Burney to emphasise and exaggerate – the freedom that the mask at Mr Lalauze’s had given her not to hide her true colours, but to reveal them.

The habit of writing, whether it was her journal or creative ‘vagaries’, and the secretive solitude it required became such pleasures to Fanny that she resented other calls on her time. The social duties of adult life that obliged women to be forever receiving and returning visits and performing ‘constrained Civilities to Persons quite indifferent to us’9 left her cold. ‘Mama’ was very keen on these civilities (she no doubt saw them as essential in a household full of girls in the marriage market), and one of Fanny’s outbursts in her journal hints at the tensions that were arising from the new regime:

those who shall pretend to defy this irksome confinement of our happiness, must stand accused of incivility, – breach of manners – love of originality, – & God knows what not – nevertheless, they who will nobly dare to be above submitting to Chains their reason disapproves, they shall I always honour – if that will be of any service to them!10

The cryptic references to ‘Chains’ and ‘defiance’ indicate the dramatic terms in which the teenaged Burney girls saw their struggle against ‘Mama’ and her set ideas about a woman’s destiny. At this point in her life, Fanny had no thought of her writings being published or even read by anyone other than ‘Nobody’, or Susan at the very most, but writing already defined her sense of autonomy, in terms both of what she wrote and the liberty she required to write it.

Fanny’s invention of the deliberately trivialising term ‘scribbleration’ for her writing was a sort of disclaimer, disassociating herself from authorship, which was the preserve of the venerated ‘class of authors’. Her father was about to join that class himself, in the same year (1769) that he finally took his doctorate in music at Oxford. When a friend called Steele suggested that Burney wasn’t making enough of his new academic title, and urged him to change his door-plate, the new doctor replied, self-consciously slipping into dialect, ‘I wants dayecity, I’m ashayum’d!’11 Want of ‘dayecity’ – or the affectation of such – ran even stronger in his daughter. When her father was in Oxford for the performance of his examination piece, Fanny sent him some comic verses that she had composed to mark the occasion. He was so amused that he read them aloud to casual acquaintances in Oxford, and teased her when he got home by reciting them in front of the family. Fanny tried to snatch the verses from him, but he carried on, and all she felt she could do was run out of the room. Her delight that he was not angry at her ‘pert verses’12 made her creep back again, though, to hear his praises surreptitiously. It was a premonition of all her later fears and ambivalence about the reception of her work and her father’s approval of it in particular.

Charles Burney’s doctorate (which was, of course, soon brazened – Steele’s pun – on the Poland Street door) conferred an authority which was helpful to his self-esteem and to the new turn he wanted his career to take. In October his first book, a short, businesslike Essay towards a history of the principal comets that have appeared since 1742, was published. The subject was timely and topical; astronomy was fashionable, and 1769 was the year in which Halley had predicted the return of his comet ‘in confirmation of the theory of the illustrious Sir Isaac Newton’. But though Burney’s little book shows his commercial instincts at work (it sold well enough to be reprinted the following year), it had a personal significance as well, being a form of homage to the dead Esther. Years before, she had made a translation of the French scientist Maupertuis’s ‘Letter upon Comets’, purely from ‘love of improvement’, according to Fanny13 (rather like Fanny’s own youthful translation of Fontanelle). Esther’s interest in astronomy had fuelled her husband’s – she might well have been looking forward to the reappearance of the great comet herself. Charles Burney revised the translation and wrote his own essay as a companion piece, a gesture which was not lost on their daughter. In the Memoirs she describes the work as a joint project by her parents, and prefaces her remarks with the apparently irrelevant information that the second Mrs Burney was staying in Norfolk at the time of its production – as if the book constituted some kind of secret assignation between Burney and his dead wife. At the distance of more than fifty years, Fanny wrote portentously about her father’s first step into print, and was in no doubt who should take the credit: her mother’s pure ‘love of improvement’ had ‘unlocked […] the gates through which Doctor Burney first passed to that literary career which, ere long, greeted his more courageous entrance into a publicity that conducted him to celebrity’.14

The Essay was only a short work but it kept Dr Burney up late at night, and its completion was followed by an acute bout of rheumatic fever. The pattern of overwork, hurry and collapse during the composition of his books may have impressed the Doctor’s daughter with the idea that writing was something urgent, difficult and heroic. Burney had by this time formulated the plan for his General History of Music, the first scholarly attempt in English to cover the development of the subject from ancient times to his own day. To choose a project so massive and challenging suggests that Burney had tired of dabbling and wanted a surefire ticket to fame (and fortune, of course), to be the author of a work which would virtually put itself beyond criticism on account of its novelty, authority and sheer size, and which, like the Dictionary of his admired Johnson, would contribute substantially to knowledge, in an age when all the best minds of Europe seemed engaged on writing works of reference.

Burney felt that his book would only make the proper impact if it derived from original research in the great music libraries of Europe, also that ‘the present state of modern music’ was the most important part of his subject. Armed with letters of recommendation from his influential friends to British officials in France and Italy, he set off on a six-month Continental tour in June 1770. It was an arduous but extremely productive journey, and though Burney was in a state of collapse on his return, he had met many famous and learned people, including Padre G.B. Martini in Bologna, the foremost musicologist of the time, the castrato Farinelli in Venice, the seventy-five-year-old Voltaire at Ferney (by an engineered accident), and in Paris Denis Diderot and the great Rousseau himself. The ‘Man Mountain’ was sitting in a dark corner, wearing a woollen nightcap, greatcoat and slippers, an informal reception which perhaps encouraged Burney to show him his plan for the History, which to the budding author’s delight, and after a little initial resistance on Rousseau’s part, went down encouragingly well.

Burney kept a detailed journal of his tour, and soon after his return to London began to think of publishing it as a money-spinner and as an advertisement for the forthcoming History. With the help of the girls, he had a manuscript ready within four months which was published in May 1771 as The Present State of Music in France and Italy. The market for ‘tour’ books was saturated at the time, but Burney’s had the novelty of its focus on music and performers, as well as gripping passages about the difficulties of travel, such as this description of crossing the Apennines:

At every moment, I could only hear them cry out ‘Alla Montagna!’ which meant to say that the road was so broken and dangerous that it was necessary I should alight, give the Mule to the Pedino, and cling to the rock or precipice. I got three or four terrible blows on the face and head by boughs of trees I could not see. In mounting my Mule, which was vicious, I was kicked by the two hind legs on my left knee and right thigh, which knocked me down, and I thought at first, and the Muleteers thought my thigh was broken, and began to pull at it and add to the pain most violently.15

The reviews of the book would probably have been good anyway, but Burney, in his acute anxiety to succeed, fixed the two most influential ones, in the Monthly Review and the Critical Review.16 He described himself as a ‘diffident and timid author’,17 but he had a ruthless streak, especially when it came to nobbling the opposition (as he did shamelessly when a rival History of Music, by Sir John Hawkins, appeared before his own). His later anxieties about his daughter’s literary career centred on the possible critical reception of her books; he felt it better for her not to publish at all than to risk adverse reviews.

With their father’s absence abroad in 1770, followed by the rush to write his book, and another long trip to Europe in 1772 to gather material for a sequel, the Burney children were left even more than usual in the undiluted company of their stepmother. While the Doctor was in Italy, Mrs Burney found and purchased a new home for the amalgamated Burney-Allen household. It was a large, luxurious house on the south side of Queen Square, an area familiar to the children from their long association with Mrs Sheeles’s school (Burney’s appointment there lasted from 1760 to about 1775). Fanny liked the open view of the villages of Hampstead and Highgate to the north, and rooms that were ‘well fitted up, Convenient, large, & handsome’, but regretted leaving Poland Street, which represented the old days of her parents’ marriage.

One of the reasons for the move was to get away from the family’s former neighbour Mrs Pringle, at whose house the Burney girls had met Alexander Seton, the baronet’s son who had been so impressed with Fanny’s conversational powers. His flirtation with Hetty had been so on-and-off for the past two years that she felt forced to give up seeing him altogether for her own peace of mind, and Mr Crisp’s advice (backed up by ‘Mama’) was that the Burneys should end contact with Mrs Pringle too. Fanny was pained to cut her old friend, but did it all the same, and was ready with some lies when the puzzled matron asked what the matter was. In all ‘difficult’ dealings of this kind, the Burneys displayed unattractive qualities: panic, fudging and petty cruelty, such as in the case of their former friend Miss Lalauze, whom they treated with a species of horror after she was reputed to have ‘fallen’. Their own struggle to sustain their upward mobility seems to have prevented them from behaving more magnanimously to such people ‘however sincerely they may be objects of Pity’.18

Hetty recovered from her disappointment over Seton (and avoided having to join the new step-household) by marrying her cousin and fellow musician Charles Rousseau Burney in the autumn of 1770. Dr Burney was abroad at the time and unable to give his consent. He would not have approved the match; he was very fond of his nephew, a gentle, talented man, but knew as well as anyone how hard it was to make a decent living out of music. The marriage was happy, but never prosperous materially. Before long, Hetty was expecting the first of her eight children (the last of which was born as late as 1792). Her career as a harpsichordist was of course over. Fanny, as the eldest unmarried daughter, now acquired the title ‘Miss Burney’.

At about the same time, Maria Allen was jilted by a young man called Martin Rishton. To cheer her up after this disappointment, Fanny wrote her a poem called ‘Female Caution’, which contains these stanzas:

Ah why in faithless man repose

The peace & safety of your mind?

Why should ye seek a World of Woes,

To Prudence and to Wisdom blind?

Few of mankind confess your worth,

Fewer reward it with their own:

To Doubt and Terror Love gives birth;

To Fear and Anguish makes ye known.

[…] O, Wiser, learn to guard the heart,

Nor let it’s softness be its bane!

Teach it to act a nobler part;

What Love shall lose, let Friendship gain.

Hail, Friendship, hail! To Thee my soul

Shall undivided homage own;

No Time thy influence shall controll;

And Love and I – shall ne’er be known.19

This accomplished poem, which, strangely, has never found its way into any anthology of eighteenth-century verse, displays an advanced state of sexual cynicism in its eighteen-year-old author; men, she claims, do not have it in their nature to be constant, and are interested only in the process of conquest. Friendship (with women) is the only way to guarantee happiness; only among women can ‘sensibility’ and ‘softness’ survive undamaged. The fop and the cad were worrying social phenomena, coarse, worldly and unmarriageable. Fanny targeted such men in her novels and created heroes who presented a new ‘feminine’ ideal of masculinity, heroes who were (sometimes absurdly) super-sensitive, rational and gentle. Fanny admired, even idealised, older men such as Crisp, Garrick and the agriculturalist Arthur Young (who was married to Elizabeth Allen Burney’s sister Martha), appreciated male gallantry and wit, and yearned romantically for an ideal male companion – but she didn’t expect to find one. Her high standards were to cause her some trouble in an age when early marriage was the expected, and only really acceptable, fate of womankind.

Extrovert Maria Allen was the moving force behind several amateur theatrical productions in the Burney household and at Chesington in which Fanny was persuaded to take part, though few actors could ever have performed so consistently badly. Fanny was loath to perform in any way, being subject to terrible stage-fright that almost certainly originated in her stigmatisation as a ‘dunce’ in early childhood. Though at least one of the plays she took part in (Colley Cibber’s The Careless Husband) was meant to be an exercise in overcoming stage-fright for the benefit of Dr Burney’s former singing pupil Jenny Barsanti, who was giving up her career as a singer to become an actress (she went on to be the first Lydia Languish in Sheridan’s The Rivals), nothing could distract Fanny from her own performance and its possible shortcomings. Howevermuch she wanted to join in with the gaiety and diversion of a family play-party, the moment when she had to appear, or speak, was one of disabling terror, as on this occasion at her uncle’s house in Worcester, where her cousins were putting on a production of Arthur Murphy’s The Way to Keep Him:

Next came my scene; I was discovered Drinking Tea; – to tell you how infinitely, how beyond measure I was terrified at my situation, I really cannot […] The few Words I had to speak before Muslin came to me, I know not whether I spoke or not, – niether [sic] does any body else: – so you need not enquire of others, for the matter is, to this moment, unknown.20

Fanny had a ‘marking Face’21 and was a violent blusher. ‘Nobody, I believe, has so very little command of Countenance as myself!’ she complained to Susan on one of the many occasions when her ‘vile Colouring’ gave her acute embarrassment. The causes of her embarrassment varied enormously. It was knowingness, not innocence, that made her self-conscious in front of people such as Richard Twiss, a traveller who on his first visit to the Burney household in 1774 indulged in very ‘free’ conversation with Dr Burney about the prostitutes in Naples. Asked by Twiss whether she knew what he meant by a ragazza, Fanny records, ‘I stammered out something like niether [sic] yes or no, because the Question rather frightened me, lest he should conclude that in understanding that, I knew much more.’22 The inference of course is that she did know ‘much more’. She certainly knew enough about John Cleland’s erotic Dictionary of Love to be embarrassed by Twiss’s reference to it on the same occasion. ‘Questa signora ai troppo modesta’, he said to Charles Burney of the blushing young woman he had been goading all evening, demonstrating the truth of James Fordyce’s observation in his Sermons that many men find ‘shyness’ in women attractive sexually as well as morally. Fordyce implies that ‘the precious colouring of virtue’ on a girl’s cheeks is the equivalent of showing a red rag to a bull: ‘Men are so made,’ he sighs complacently.23 But Fanny was much more likely to have agreed with Jonathan Swift’s acid judgement of female ‘colouring’: ‘They blush because they understand.’24

Nevertheless she was highly resistant to sexual flattery, and too self-conscious to be vain. In her copious diary, she hardly ever mentions dress, although much of the needlework that the Burney girls, like all women of their class, were expected to do daily consisted in making and mending their own clothes. She disliked needlework and was not particularly good at it; if her clothes were ever eye-catching, it may not have been for the right reasons. Her best gown in 1777 was simply referred to as her ‘grey-Green’, presumably a silk or ‘tabby’, chosen to match the colour of her eyes.

Fanny Burney was quick to satirise the absurdities of fashion and personal vanity in her works: in Evelina the London modes provide plenty of humour, especially the mid-1770s fashion among women for high hair. In the novel, Miss Mirvan makes herself a cap, only to find that it won’t fit over her new coiffure, and Evelina herself, the country girl agog at the novelty of going ‘a-shopping, as Mrs Mirvan calls it’25 (it was a very recently coined word), gives an insider’s account of being pomaded, powdered and pinned:

I have just had my hair dressed. You can’t think how oddly my head feels; full of powder and black pins, and a great cushion on the top of it. I believe you would hardly know me, for my face looks quite different to what it did before my hair was dressed. When I shall be able to make use of a comb for myself I cannot tell for my hair is so much entangled, frizzled they call it, that I fear it will be very difficult.26

In Fanny’s play The Witlings, the first scene is set in a milliner’s shop, among the ribbons and gee-gaws that recur in her works as symbols of luxury and waste. The shop girls are slaves to appearances: Miss Jenny has no appetite because ‘she Laces so tight, that she can’t Eat half her natural victuals,’ as one of the older women observes. ‘Ay, ay’, replies another, ‘that’s the way with all the Young Ladies; they pinch for their fine shapes’.27 The unnaturalness of fashion struck Burney forcibly (as well it might in the age of hoops, stays, corsetry, high hair and silk shoes), but she also despised its triviality and the hold it had over so many women’s lives, confirming them in the eyes of unsympathetic men as inferior beings. In her play The Woman-Hater, misogynistic Sir Roderick describes womankind as ‘A poor sickly, mawkish set of Beings! What are they good for? What can they do? Ne’er a thing upon Earth they had not better let alone. […] what ought they to know? except to sew a gown, and make a Pudding?’28

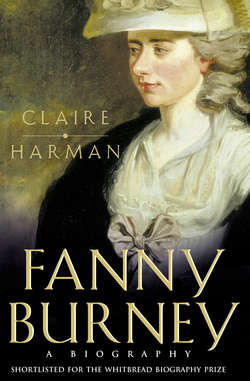

Each of Burney’s novels contains some insight into the extent to which women are unfairly judged by their appearance. She was never very pleased with hers. Like all the Burneys she was very short – Samuel Johnson described her affectionately as ‘Lilliputian’29 – and slightly built, with very thick brown hair, lively, intelligent eyes and her father’s large nose. She had an inward-sloping upper lip inherited from her mother (Hetty and Susan had the same), small hands and narrow shoulders. The portrait painted by her cousin Edward Francesco Burney in 1782 shows a gentle, intelligent and attractive face. She thought he had flattered her horribly, but how many portrait painters do not idealise their sitters, especially when, like Edward, the artist is also an admirer? His second portrait of her, painted only two years later (it now hangs in the National Portrait Gallery), has her face partly shadowed by an enormous hat. Her look is more thoughtful, slightly uncomfortable, but the benignly intelligent expression is the same.

Fanny Burney’s short sight caused her trouble all her life and undoubtedly affected her behaviour. She became mildly paranoid about being scrutinised by other people because she couldn’t see their expressions clearly and only felt really comfortable with things which fell within the circle of her vision, such as books, writing and intimate friends. Short sight affected her writing too; the novels are remarkable for the avoidance of physical description and heavy reliance on dialogue to delineate character. Fanny owned an eye-glass, but was often inhibited from using it; at Lady Spencer’s in 1791 she ‘did not choose to Glass’ the company ‘& without, could not distinguish them’.30 At court in the 1780s, the use of the eye-glass was, presumably, limited by protocol and many embarrassing incidents ensued when Fanny did not identify the King or Queen in time to respond correctly. She doesn’t seem to have owned a glass in 1773 when she went to a performance at Drury Lane by the singer Elizabeth Linley one month before that siren’s marriage to Richard Brinsley Sheridan; she could only make out Miss Linley’s figure […] & the form of her Face’.31 By 1780, however, she could be pointed out at the theatre as ‘the lady that used the glass’.32 Understandably, she hated to have attention drawn to her disability, and scorned one of Mrs Thrale’s acquaintance for suggesting that she could not see as far as the fire two yards away by answering his question ‘How far can you see?’ with a comical put-down; ‘O – I don’t know – as far as other people, but not distinctly’.33

Fanny’s constitution was basically strong, but easily affected by nervous ailments and stress. ‘[H]er Frame is certainly delicate & feeble’, Susan noted in her journal. ‘She is quickly sensible of fatigue & cannot long resist it & still more quickly touched by any anxiety or distress of mind’.34 Fanny endured remarkable pain, both physical and mental, in the course of her long life, and survived the appalling mutilation of the mastectomy she underwent for cancer in 1811 with astonishing tenacity and powers of recuperation, yet she appears to have been something of a hypochondriac in her youth, impressed with a belief in her own fragility and half-expecting to die young, like her mother. When Mrs Thrale once exclaimed against the idea of Fanny marrying a man old enough to be her father, Fanny replied, ‘I dare say he will Live full as long as I shall, however much older he may be’.35 The character of being frail, insubstantial, almost No-body, was oddly compelling, and she recorded with evident satisfaction the playwright Dr John Delap’s remark in 1779 that she was ‘the charmingest Girl in the World for a Girl who was so near being nothing, & they all agreed nobody ever had so little a shape before, & that a Gust of Wind would blow you quite away’.36 The ‘Girl’ was, at this date, twenty-seven years old, unmarried, unhappy at being exposed to the public as a writer and not eating well.

Fanny’s attitude to food and eating immediately suggests some sort of disorder. References to food in her journals and works are infrequent, and never enthusiastic or appreciative. She knew, as we have seen from The Witlings, about young women starving themselves to get into smallsized clothes; she also knew about bingeing. In The Woman-Hater, Miss Wilmot’s unabashed relish for food is seen as a mark of her lack of feminine delicacy, and she characterises her old life of restraint and decorum as ‘sitting with my hands before me; and making courtsies; and never eating half as much as I like, – except in the Pantry!’37 Whether the Burney girls, singly or in gangs, raided the pantry in Poland Street or Queen Square is a matter for speculation, but in public Fanny was a very small eater. ‘I seldom Eat much supper’, she said to Twiss when he remarked on her pickiness.38 The diaries show her at various times satisfied with one potato,39 overpowered by the thought of a rasher40 and alert to the grotesque aspects of ingestion, as a letter to Susan in March 1777 reveals:

Our method is as follows; We have certain substances, of various sorts, consisting chiefly of Beasts, Birds, & vegetables, which, being first Roasted, Boiled or Baked […] are put upon Dishes, either of Pewter, or Earthern ware, or China; – & then, being cut into small Divisions, every plate receives a part: after this, with the aid of a knife & fork, the Divisions are made still smaller; they are then (care being taken not to maim the mouth by the above offensive weapons) put between the Lips, where, by the aid of the Teeth, the Divisions are made yet more delicate, till, diminishing almost insensibly they form a general mash, or wad & are then swallowed.41

This exercise in comic detachment is in part a send-up of the congenial dullness of life at Chesington Hall, intended to make Susan laugh, but it is revealing in other ways. While reducing the act of eating to its constituent parts, chewing over the very idea of eating, Fanny never touches on the sensual aspects – the smell, sight or taste of food. Food is simply matter to be made into smaller and smaller divisions ‘almost insensibly’, then swallowed in a ‘mash’ or ‘wad’. She writes about eating as if it were a merely mechanical process, pointless and therefore slightly disgusting.

Fanny’s small appetite (and her appetite for being small) was a form of self-neglect which had several other symptoms. Samuel Crisp complained about her unbecoming stoop and habit of sitting with her face short-sightedly close to the page when she was reading or writing. She was also criticised for mumbling, pitching her voice too low and being silent in company. Clearly, people felt she wasn’t making enough of an effort, wasn’t ‘doing herself justice’; and they were right.

Fanny Burney was in no hurry to get married – in fact the idea filled her with dread. ‘[H]ow short a time does it take to put an eternal end to a Woman’s liberty!’ she had exclaimed, watching a wedding party emerge from the church in Lynn.42 Her father was her idol, and she had no intention of quitting him. ‘Every Virtue under the sun – is His!’ she wrote unequivocally.43

Many men in the Burneys’ wide and constantly shifting circle of acquaintance were attracted to Fanny, and she made several conquests despite her reputation for prudery and refusal to play the coquette, an activity she found degrading to both sexes. Like the heroines of her novels, she was confident that virtue was at the very least its own reward. Her ‘quickness of parts’ and sense of humour were only revealed to those men she felt worthy to appreciate them, such as Alexander Seton; others were shown the ‘prude’ front. This was as much a matter of propriety and fairness as anything else. ‘I would not for the World be thought to trifle with any man’, she once wrote to Crisp, and her lifelong behaviour bore out the sincerity of the remark.

The first proposal of marriage Fanny received, in the summer of 1775, provoked a crisis. The hopeful suitor, a Mr Thomas Barlow, was a decent, honest twenty-four-year-old, good-looking and reasonably well-off, who became earnestly enamoured of Fanny after one cup of tea in the company of some friends of Grandmother Burney. Fanny’s aunts, sister and grandmother, in sudden, ominous collusion, strongly approved of the match, but Fanny was unmoved. She thought her polite rejection of Barlow marked the end of the story, but the opposition was marshalling its forces. Hetty had written to Crisp about the affair, and he wrote Fanny a long letter, blatantly working on what he imagined might be her worst fears. Did she, he asked, want to be

left in shallows, fast aground, & struggling in Vain for the remainder of your life to get on – doom’d to pass it in Obscurity & regret – look around You Fany [sic] – look at yr Aunts – Fanny Burney wont always be what she is now! […] Suppose You to lose yr Father – take in all Chances. Consider the situation of an unprotected, unprovided Woman.44

Fanny replied to this harangue with courage. Pointing out how unwise Crisp was ‘so earnestly to espouse the Cause of a person you never saw’, she told him that she had resolved never to marry except ‘with my whole Heart’, be the consequences what they may. She was not so afraid of becoming an old maid that she could accept ‘marriage from prudence & Convenience’, and gently deflected Crisp’s fears for her future provision by saying, ‘Don’t be uneasy about my welfare, my dear Daddy, I dare say I shall do very well’.45 Did she think that her writing, still secret to all but Susan, might one day earn her money? Or was this an expression of confidence in her father, in whose career she had such a close interest? ‘[S]o long as I live to be of some comfort (as I flatter myself I am) to my Father’, she grandly told Crisp, ‘I can have no motive to wish to sign myself other than his & your […] Frances Burney’.

Fanny’s confidence collapsed, though, when her father suddenly added his voice to those urging her to reconsider Barlow’s proposal. The suggestion that Charles Burney could live without her was a body-blow:

I was terrified to Death – I felt the utter impossibility of resisting not merely my Father’s persuasion but even his Advice. […] I wept like an Infant – Eat nothing – seemed as if already married – & passed the whole Day in more misery than, merely on my own account, I ever did before in my life[.]46

The crisis resolved itself the next day in a tearful scene between father and daughter, during which Fanny declared that she wanted nothing but to live with him. ‘My life!’ the Doctor exclaimed, kissing her kindly, ‘I wish not to part with my Girls! – they are my greatest Comfort!’ Fanny left the room ‘as light, happy & thankful as if Escaped from Destruction’.47

To Mrs Burney, the matter must have presented itself rather differently. The girls were not her greatest comfort, and seemed perversely determined not to marry well. Esther had made an impoverished love-match; in 1772 both Maria Allen and her seventeen-year-old brother Stephen shocked and offended their mother by runaway marriages – Maria with Martin Rishton, her former jilt, and Stephen with a girl called Susanna Sharpin. Now Fanny was declaring she would probably never marry, but wanted only to live with her father. With Fanny hunkering down after the Barlow episode as a possibly permanent fixture at home, relations between her and ‘Mama’ began to stiffen.

Progress with the History of Music was much slower than Dr Burney had anticipated, and although he was working at it obsessively and making as much use as possible of his daughters as secretaries and his new friend the cleric and scholar Thomas Twining as an adviser, it began to look as if he had taken on too much. He had other disappointments and difficulties at the same time, including the failure of his plans to found a school of music with the violinist Giardini and, a few weeks later, the publication of a raucous parody of his two books of travels (The Present State of Music in Germany, the Netherlands and the United Provinces had been published the previous year), satirising the credulity and affectation of earnest fact-gatherers such as the Doctor in a succession of absurd and often quite amusing ‘musical’ encounters around England. Burney was deeply alarmed and offended by the pamphlet, and is believed to have tried to suppress it by buying up the entire stock,48 a drastic measure which (if he took it) did not prevent the work going through four editions in the next two years. In the Memoirs Fanny made as light of the incident as she could, though she betrays her strong feelings in metaphors of ‘vipers’ and ‘venom’. According to her, the pamphlet ‘was never reprinted; and obtained but the laugh of a moment’,49 but there was a great deal in the squib to touch her own feelings as nearly as it had the Doctor’s. If he, with his Oxford doctorate, could attract a lurid parody of his books about music, what treatment might not an uneducated female would-be novelist expect?

In the autumn of 1774 the Burneys were forced to leave Queen Square because of ‘difficulties respecting its title’.50 The house they moved to was right in the centre of town, on the corner of Long’s Court and St Martin’s Street, which runs south out of Leicester Square. Although the air was not so balmy as in Queen Square, with its ‘beautiful prospect’, and though St Martin’s Street was, in Fanny’s blunt words, ‘dirty, ill built, and vulgarly peopled’,*51 there were many things to recommend the new address. It was convenient for the opera house and the theatres, the aunts in Covent Garden, Hetty and her young family in Charles Street and many of Dr Burney’s fashionable friends (Sir Joshua Reynolds lived just round the corner in Leicester Square). It also had the distinction of having been Sir Isaac Newton’s house, which alone would have recommended it to the astrophile Burneys. Newton lived there from 1711 to his death in 1727, and built a small wooden observatory right at the top of the property, glazed on three sides and commanding a good view of the city as well as the sky. ‘[W]e shew it to all our Visitors, as our principal Lyon’, Fanny wrote in her journal ten days after moving in.

The Burneys were so proud of the connection with the great scientist that they thought of calling their new home ‘Newton House’ or ‘The Observatory’ as a boast. Charles Burney was particularly fond of dropping Sir Isaac’s name into conversation, and displayed a certain ingenuity at creating occasions to do so. Once when a visitor broke his sword on the stairs Burney protested that they ‘were not of my constructing – they were Sir Isaac Newton’s’;53 and on Mrs Thrale’s first visit to the house he said he was unable to ‘divine’ the answer to a query about a concert, ‘not having had Time to consult the stars, though in the House of Sir Isaac Newton’.54 As a sort of homage to their illustrious precursor, Burney spent a considerable sum having the observatory renovated. He did not, however, choose the chilly rooftop perch for his study (a small room adjoining the library on the first floor performed that function much more comfortably), and it was soon colonised by the children, Fanny adopting it as her ‘favorite sitting place, where I can retire to read or write any of my private fancies or vagaries’ – a substitute for her closet or ‘bureau’ of former days.

Of all the Burneys’ homes, number 1 St Martin’s Street is the most famous.* Dr Burney and his wife lived there for thirteen years, by the end of which the children, with the exception of their younger child, Sarah Harriet (born in 1772), had all left home. The house had a basement and three storeys each consisting of a front and back room, with a projecting wing to the rear on each floor. On the ground floor at the front was the panelled parlour where the family took their meals,† and behind it was another parlour (the kitchen, presumably, was in the basement). Above it, up the fine oak staircase, was the drawing room, with three tall windows looking onto St Martin’s Street. This room was the most splendid in the house, and had an ‘amazingly ornamented’ painted ceiling, probably depicting nudes, since it seems to have been something of an embarrassment to the Doctor: ‘I hope you don’t think that I did it?’ he said to one curious visitor, ‘for I swear I did not!’56 Sir Isaac’s name was not invoked on this occasion. There had been three other owners since the scientist, one of them French.

The drawing room was separated from the library by folding doors which, when opened, provided a large and elegant space for the many parties and concerts which the Burneys soon began to hold at St Martin’s Street. Dr Burney’s library was extensive and highly specialised: when Samuel Johnson visited for the first time and abandoned the company to inspect the books, he would have found few volumes on any subject other than music (although he still preferred looking into books on music to attending the Burneys’ informal concert which was the alternative entertainment). The library, also known as the music room, had a window looking down onto the small, overshadowed garden at the back and contained the Doctor’s two harpsichords. Beyond it, in the part of the building which projected out at the back, was Burney’s narrow workroom, grandly named ‘Sir Isaak Newton’s Study’ (on hearsay), but commonly known as ‘the Spidery’ or ‘Chaos’ and habitually so untidy with Burney’s sprawl of papers that no guests were invited to look in.

On the top floor at the front was the main bedroom, used by Dr and Mrs Burney, with a powdering closet adjoining. The girls’ bedroom was beyond it at the back, above the library. The three attic rooms, from which one gained entrance to the observatory, were probably servants’ bedrooms and the nursery, with a poky stairway leading from the top floor. James was scarcely ever at home, but still had a room on the ground floor kept for him that opened onto the little garden; Charles junior probably slept there when he was home in the holidays from Charterhouse. Beyond ‘Jem’s room’, opening onto Long’s Court, was a small workshop, which Dr Burney rented to a silversmith. It is likely that the workshop created some noise and smell around the back of the house, a reminder of trade going on only just out of sight and earshot of the elegant drawing room. The back of the workshop and its yard would have been visible though from the girls’ bedroom window and the eastfacing side of the observatory.

The household in the autumn of 1774 consisted of the Doctor and his wife, both approaching fifty, Fanny (who, aged twenty-two, might not have been expected to be at home for much longer), Susan, aged nineteen, thirteen-year-old Charlotte, the lively six-year-old Richard and toddler Sally, then as always a rather neglected little girl. Small children were never going to be a novelty in the Burney household. When the family moved into St Martin’s Street, Esther was only a few weeks away from giving birth to her third child, Charles Crisp Burney, having had Hannah Maria in 1772 and Richard in 1773, the first three of Dr Burney’s eventual total of thirty-six grandchildren.

The move to St Martin’s Street took place while Charles Burney was recuperating from another bout of rheumatic fever. He was confined to bed for weeks, but carried on work on the History by dictating to Fanny and Susan. The family did not hold a large party at the new house until March 1775 on account of this indisposition, but the publication of The Present State of Music in Germany […] in 1773 had significantly increased Burney’s standing as a writer as well as a historian of music, and there was no stopping the flow of illustrious visitors passing through London who wanted an introduction to him. Fanny’s letters to Crisp in 1774 and 1775 contain many highly entertaining set-pieces describing some of these callers. The first was the most exotic, a young native of the Society Islands called Omai who had come to England on board the Adventure with James Burney. James, who had finished his training as an able seaman in 1771, had joined Captain Cook’s second voyage to the Antarctic Circle the following year, returning to England in July 1774. He had mastered some Tahitian on the voyage home and was able to act as interpreter to ‘lyon of lyons’ Omai, who was fêted all round London, received by the King and invited to the houses of aristocrats keen to observe and display a living emblem of the nation’s South Sea discoveries. Omai arrived at the Burneys’ house in the company of Joseph Banks and Daniel Solander, the botanists who had accompanied Cook on his first circumnavigation of the globe. His manners impressed Fanny extremely favourably; even though he had very little English, the Polynesian ‘paid his Compliments with great politeness […] which he has found a method of doing without words’.57 Fanny sat next to him at dinner and noticed how unostentatiously alert Omai was to the feelings of others, glossing over the servant’s mistakes and assuring Mrs Burney that the (tough) beef was actually ‘very dood’. He ‘committed not the slightest blunder at Table’, and didn’t fuss over his new suit of Manchester velvet with lace ruffles, although it was totally unlike his native costume (or the fantasy burnous in which he was painted by Reynolds during his visit). ‘Indeed’, wrote Fanny to Crisp, ‘he appears to be a perfectly rational & intelligent man, with an understanding far superiour to the common race of us cultivated gentry: he could not else have borne so well the way of Life into which he is thrown’. With his spotless manners and spotless ruffles, Omai could not have been a more perfect example of Noble Savagery, showing up the gracelessness of the expensively educated ‘Boobys’ around him in a way that the future satirist found highly gratifying. ‘I think this shews’, she concluded grandly, ‘how much more Nature can do without art than art with all her refinement, unassisted by Nature.’58

Their next notable visitor was one of the most famous singers of the day, the Italian soprano Lucrezia Agujari, known rather blatantly as ‘La Bastardina’. Mozart had met her in 1768 and marvelled at her astonishingly high range: she had, in his presence, reached three octaves above middle C – a barely credible achievement. She was virtuosa di camera to the court of the Duke of Parma, whose master of music, Giuseppe Colla, ‘a Tall, thin, spirited Italian, full of fire, & not wanting in Grimace’,59 was her constant companion. Susan Burney had got the impression – not unreasonably – that the couple were married, and that La Bastardina retained her maiden name for professional purposes. This led Hetty to cause the singer some consternation by enquiring if she had any children: ‘Moi!’ she exclaimed disingenuously, ‘je ne suis pas mariée, moi!’60

The Burneys were of course all craving to hear Agujari sing, but Signor Colla explained that a slight sore throat prevented it. ‘The singer is really a slave to her voice’, Fanny noted in her journal; ‘she fears the least Breath of air – she is equally apprehensive of Any heat – she seems to have a perpetual anxiety lest she should take Cold; & I do believe she neither Eats, Drinks, sleeps or Talks, without considering in what manner she may perform those vulgar duties of Life so as to be the most beneficial to her Voice.’ Agujari was contracted at huge cost to sing at the Pantheon on Oxford Road (a new venue for concerts and assemblies that was proving immensely popular and in which Charles Burney had shares), and though she promised to return and sing for the Burneys at some later date, the possibility seemed remote. Months passed and they heard nothing of her, only jokes based on the story that she had been mauled by a pig when young and had had her side repaired with a silver plate. Lord Sandwich, First Lord of the Admiralty at the time, showed Charles Burney a satirical song he had written on the subject and wanted to have set to music. It was a dialogue between Agujari and the pig, ‘beginning Caro Mio Porco – the Pig answers by a Grunt; – & it Ends by his exclaiming ah che bel mangiare!’61 It is interesting to note that although the parody of her father’s book had struck Fanny as scandalous, she was quite happy to join in and pass on jokes about Agujari’s ‘silver side’. It presented ‘too fair a subject for Ridicule to have been suffered to pass untouched’.

It wasn’t until June that Agujari did sing for the Burneys, and then all jokes about her person and criticism of her affectations were forgotten. ‘We wished for you! I cannot tell you how much we wished for you!’ Fanny wrote ecstatically to Crisp:

I could compare her to nothing I ever heard but only to what I have heard of – Your Carestino – Farinelli – Senesino – alone are worthy to be ranked with the Bastardini. Such a powerful voice! – so astonishing a Compass – reaching from C in the middle of the Harpsichord, to 2 notes above the Harpsichord! Every note so clear, so full – so charming! Then her shake – so plump – so true, so open! it is [as] strong & distinct as Mr Burney’s upon the Harpsichord.62

Agujari certainly did not stint her hosts. She stayed for five hours, singing ‘almost all the Time’, arias, plain chant, recitative: ‘whether she most astonished, or most delighted us, I cannot say – but she is really a sublime singer’. There was no more talk of their exotic visitor being ‘conceitedly incurious’ about her rivals: ‘her Talents are so very superior that she cannot chuse but hold all other performers cheap’.63 The generous free recital, the sublime voice, the plump shake had all done their work. Fanny and her sisters became Agujari’s besotted devotees.

In his Surrey retreat, Crisp hung on these bulletins, especially the accounts of musical evenings. On one memorable occasion in 1773 recorded by Fanny, the party consisted of the violinist Celestini, the singer Millico and the composer Antonio Sacchini, ‘the first men of their Profession in the World’.64 Fanny could describe in detail evenings out, say at the opera, where they had gone to hear Agujari’s rival Gabrielli, and reproduce the long discussions about the performances afterwards, with what seems to be remarkable accuracy. The guests at one of the Doctor’s musical evenings that summer and autumn included Viscount Barrington, then Secretary at War, the Dutch Ambassador and Lord Sandwich, whom Charles Burney was no doubt trying to cultivate on James’s behalf. This was exciting company for the Burney girls, and the fact that Fanny relished these evenings shows that her shyness was less potent than her curiosity. Some of their guests were outlandish, such as Prince Orloff, the lover of Catherine the Great, who arrived at St Martin’s Street late on the appointed evening and squatted on a bench next to Susan, almost squashing her. His appearances in London had been the subject of much gossip, and here he was, dwarfing his hosts and dripping with diamonds, a portrait of the Empress indiscreetly flashing on his breast. Not that it was easy to see it – when the Burney girls were shown it the glare of the surrounding jewels was almost blinding; ‘one of them, I am sure, was as big as a Nutmeg at least’ Fanny wrote.65

Fanny’s early diaries describe a life of seemingly uninterrupted gaiety in the company of her loving sisters, adored father and some of the greatest artists of the day. The ‘abominably handsome’ Garrick continued to be a frequent visitor, loved by the whole family; on one occasion he picked Charlotte out of her bed and ran with her as far as the corner of the street. When he threatened to abduct the other girls ‘we all longed to say, Pray do!’66 But as the editors of Fanny’s diaries have pointed out, the consistently cheerful portrait of life in St Martin’s Street is deceptive, since most of the material relating to Fanny’s stepmother was destroyed. From other sources, such as a letter to Fanny from Maria Rishton in September 1776, a different picture emerges:

I knew you could never live all together or be a happy society but still bad as things used to be when I was amongst you they were meer children falling out to what they seem to be now … You know the force of her expression. And indeed I believe she writes from the heart when she says she is the most miserable woman that breathes.67

When Mrs Burney was nervous and dictatorial, the girls responded with outward deference and private ill-will. She was perceived by them as grossly insensitive; perversely, this led them to treat her with gross insensitivity, almost as if they were testing her, trying to prove their worst apprehensions. A cabal formed against ‘the Lady’, and to his shame ‘Daddy’ Crisp joined it gleefully, going so far as to be ‘excessively impudent’ to her face and satirical behind her back, ‘taking her off! – putting his hands behind him, & kicking his heels about!’68

The portrait of Mrs Ireton in Fanny Burney’s last novel, The Wanderer, seems to draw on many of the second Mrs Burney’s supposed attributes (as well as those of Fanny’s later bête noire at Court, Mrs Schwellenberg, whom she called Mama’s double). The heroine of The Wanderer, Juliet, whom Mrs Ireton oppresses from sheer bloody-mindedness and sadism, is forced to act as ‘humble companion’, a symbolic representation of Fanny’s subordination to her stepmother. An explanation for Elizabeth Burney’s ‘love of tyranny’ is suggested in the story by Mrs Ireton’s brother-in-law, who knew the old harpy in youth as ‘eminently fair, gay, and charming!’69 Perhaps the inextinguishable spleen of the Burney ‘Family Scourge’ was, like Mrs Ireton’s, a kind of shock reaction to the withdrawal of sexual attention:

without stores to amuse, or powers to instruct, though with a full persuasion that she is endowed with wit, because she cuts, wounds, and slashes from unbridled, though pent-up resentment, at her loss of adorers; and from a certain perverseness, rather than quickness of parts, that gifts her with the sublime art of ingeniously tormenting.70

Mrs Burney had plenty of fuel for sexual jealousy, not just at home among her stepdaughters (whom William Bewley had once described as Charles Burney’s ‘seraglio’) but among the Doctor’s pupils too. No doubt his male friends teased Charles Burney about his access to an endless supply of nubile young women, and perhaps not without cause: he appears in James Barry’s 1783 allegorical painting The Triumph of the Thames surrounded by naked Nereids, and in C.L. Smith’s caricature ‘A Sunday Concert’ in an obscenely suggestive pose in front of John Wilkes’s daughter Mary. Burney was clearly susceptible to female charms: he became openly infatuated with the lovely Sophy Streatfield after her lover Henry Thrale was dead, to the extent that Mrs Thrale felt he was making a fool of himself.71 Even Fanny noticed and joked about her father’s ability to make ‘conquests’, though she saw it mostly as proof of his charm. But a wife would be likely to view such persistent ‘charm’ rather differently. Elizabeth Burney may have had much more to put up with in her marriage than we know.

* Fanny’s impression differs radically from John Strype’s description of St Martin’s Street in 1720 as ‘a handsome, open Place, with very good Buildings for the Generality, and well inhabited’.52

* It was later renumbered 35. The house was condemned in 1913 and the site is now occupied by the Westminster Reference Library.

† This room in the Burneys’ house has been reconstructed at Babson College, Wellesley, Massachusetts, using the original panelling and mantelpiece.55