Читать книгу Left of the Bang - Claire Lowdon - Страница 10

Three

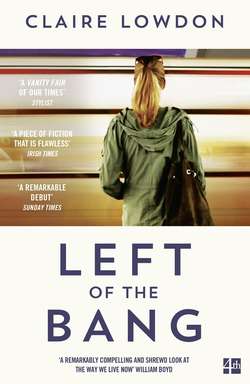

ОглавлениеFive fifteen on a Tuesday evening in late November: the crowded southbound Bakerloo line. Tamsin Jarvis, now seventeen, still very skinny, had a seat. Even better, she had the end seat. This meant she could lean right away from the woman on her left and press her hot cheek onto the pane of glass dividing the seats from the standing section. She had shrugged off her parka at Marylebone to reveal a faded black Nirvana T-shirt bearing the slogan ‘flower sniffin kitty pettin baby kissin corporate rock whore’. In her lap, a book of Beethoven piano sonatas, open at No. 21. Tamsin had been tracing the melody with a chewed-down fingernail, pleasantly conscious of the incongruity: a grungy-looking teenage girl absorbed in classical music, performing the indisputable miracle of turning black marks on the page into sounds in her head.

She didn’t notice the suitcase until the train was pulling out of Piccadilly Circus. It was a pine-green, hard-shelled case with wheels and an extendable handle, pushed up against the other side of the glass panel. How long had it been there? At Charing Cross, she looked to see if somebody claimed it. People jostled past it on their way out, irritated by the obstacle. A small woman with a scrappy high ponytail banged her knee on it and let out a bleat of pain. The woman scowled around for the owner, but no one came forward.

Almost as soon as the train had left the station, it stopped. Tamsin looked at the suitcase. Then through the window behind her at the tunnel blackness with its dirty arcana of wires and pipes. Then back at the suitcase. Someone was watching her: a tall boy about her own age, with broad shoulders and something slightly Asian, Chinese or Japanese maybe, about the eyes. He was standing in the middle of the carriage, holding the handrail with both hands, elbows flexed as if about to do a chin-up.

The boy nodded towards the suitcase.

‘Is that yours?’

Tamsin shook her head. ‘Is it yours?’ she asked, stupidly.

‘No.’ The boy leaned forward and tapped the shoulder of an older man in a pale grey trench coat. ‘Excuse me, sir: does that case belong to you?’ His voice was respectful and refined, the accent upper class without a hint of arrogance.

The man frowned, shook a no, turned back to his paper.

Tamsin and the boy each read the same thoughts in the other’s face. When the train jolted, they both jumped. But it was just a false start; another jerk and they were moving again. Tamsin looked away, suddenly sheepish. No one else seemed concerned about the case; surely they were both being paranoid.

But her gaze was drawn back. Tamsin’s mind played forward to the blast, the train carriage crumpled like a Coke can. Though of course, she wouldn’t see that. She was sitting next to the suitcase; she would be killed outright. Tamsin Jarvis, daughter of the conductor Bertrand Jarvis, was killed outright in the attacks of 25 November. Unless the pane of glass was thick enough to protect her, just to begin with. Maybe it would shatter, or melt down onto her, sticking her clothes to her skin…

At Embankment, the same thing again: one lot of passengers shuffling off, the next lot starting to push their way on prematurely. And all the time the suitcase squatting there, unclaimed. At the last minute, Tamsin stood up and burrowed to the exit. Two seconds later the tall boy followed her out. Neither of them said anything.

In the bustle of the platform, Tamsin felt their fears start to shrink into silliness. The boy headed decisively for the help-point phone, only to find it was broken. As they discussed what to do, their convictions gave way to embarrassment. At last Tamsin said, quite firmly, that she thought they had both overreacted.

The boy laughed nervously. ‘Right. Bloody hell. Don’t know about you, but I could really do with a drink.’

‘I was meant to be meeting friends in Camberwell…’ She looked up at him. There was a charming, improbable smattering of freckles across the bridge of his very straight nose. ‘But yes, a drink would be lovely, yes.’

He held out his hand, smiling for the first time. ‘I’m Chris.’

On the escalator, Tamsin felt the elation she associated with playing truant, but there was something else, too: an intimacy thrown over them first by fear and now, increasingly, foolishness. Yet at the entrance to the station, they both paused and breathed in deeply, tasting concrete in the damp November air. The world was newly sweet.

Chris took her to Gordon’s Wine Bar on Villiers Street. ‘A real gem of a place,’ he said loudly, as they made their way down the little stone staircase. The bar had low-vaulted ceilings and red candles stuck into old wine bottles, each with a dusty ruff of stalactites. The clientele was mostly male and middle-aged; but there were also some groups of younger drinkers playing for sophistication, and a fair-haired couple with matching hiking boots and a Rough Guide. Tamsin was nervous about her fake ID – thus far, she’d done most of her underage drinking in Camden pubs – so Chris, already eighteen, went up to buy the drinks. As she waited, she gazed round at the framed newspaper clippings, the cobwebs (evidently encouraged), the line-up of bottles behind the bar.

Tamsin was indulging in an old, childish game of deciding which instrument each wine bottle would be – some were square-shouldered like violins, others sloped gently from the neck like double basses – when the fear she’d felt in the tube rose up again. What if, at this very moment, people were dying because she and Chris had been too – too what? too selfish? too shy? – to act?

‘How will we know what’s happened?’ she asked Chris, as he placed a little carafe of red and two glasses on the table in front of her.

Chris shrugged. He started to pour out their wine, still standing, not meeting her eyes.

‘It was definitely nothing.’ He sat down opposite her, tucking his long legs under the table with difficulty. Tamsin waited for him to settle, then lifted her wine glass and tipped her head to one side.

‘Cheers.’

The clink of their glasses registered as a punctuation mark. Somehow, it had been agreed that neither of them would mention the suitcase again.

Their conversation was unremarkable: where they lived, what A-levels, how many siblings. Hearing in each other’s voices the same expensive educations, he confessed, a little shyly, to Rugby (‘but on a bursary, you know’), she to St Paul’s. They ascertained that, aged fourteen, they had both been to the same teenage charity ball, where a friend of Tamsin’s had kissed a record twenty-five boys in the space of two hours. Perhaps Chris had been one of them? Tamsin described her friend: tallish, dyed blonde hair, heavy eyeliner? Chris didn’t think so; the girl he had kissed that night – the first girl he had ever kissed – was a brunette with traintracks. And so to kisses, first kisses, bad kisses, aborted kisses, swapping horror stories with that world-weariness peculiar to late adolescence, dismissive and vaunting at the same time. Tamsin referenced a one-night stand, ever-so-casually, and watched Chris’s eyes widen briefly, telling against his knowing nod.

‘Right.’ Tamsin emptied the last of the carafe into Chris’s glass. ‘My turn,’ she said, bending for her handbag. ‘Wait a moment … here it is … no, fuck. Fuck, I was sure I had twenty quid.’

Chris was already on his feet. ‘It’s fine, really, I’ve got plenty – I’ll get it. Please, allow me,’ he added as Tamsin made to protest. ‘It would be my pleasure.’

These last words seemed an absurd imitation of someone older. Tamsin started to laugh; but when she saw the discomfort in Chris’s face, she softened the laugh to a giggle that was inescapably flirtatious – becoming, without quite meaning to, a girl being bought a drink by a boy who wanted to buy it for her.

He came back with a bottle this time. ‘Friend of mine, he did a gap year working in Bordeaux, just picking grapes to start with, bloody hard work … anyway, we’re meant to be tasting, what was it, blackberries, and some sort of spice, oh, it was clove, and something else a bit weird – leather, I think…’

Tamsin watched Chris’s mouth while he talked. She was trying to work out whether she fancied him. He was undoubtedly good looking and, to her, a little exotic – his Japanese father, his Hong Kong childhood. But in spite of Chris’s charm and the off-beat romance of this impromptu date, she wasn’t entirely sure she liked him. There was something in him that couldn’t function without outside approval. He wasn’t a show-off, exactly, but he needed an audience.

(Later, she would forget this. In the edited version, only the romance would remain.)

Chris’s hand hovered near the book of Beethoven Sonatas, now lying on the table underneath Tamsin’s bag. ‘Uh, may I?’

He opened it gently. ‘All these notes … I tried once, but I was no good. Think I just about made Grade 5.’ He shook his head in admiration. ‘I’d love to hear you play. Seriously, I think musicians must be the closest thing to angels.’

For a moment Tamsin thought it was a bad pick-up line; but one look at Chris’s face told her he was in earnest. She decided that she didn’t fancy him.

‘Are you going to be a professional?’

Tamsin nodded, then remembered to add a modest grimace. ‘If I make it. It’s pretty tough.’

Chris was impressed. ‘What about the rest of your family? Are they musical, too?’

‘My – yes, my mum’s a singer, actually. And my sister plays the oboe.’ Tamsin found herself reluctant to say who her father was.

Chris’s thoughts were rather more straightforward. He did fancy Tamsin, and he wanted to kiss her. She was tough and edgy and – a word that had powerful mystique for Chris – artistic. He was entranced. The more they talked, the more certain he felt that they had been brought together by fate and irresistible mutual attraction. Everything about the evening seemed tinged with inevitability.

They had had nothing to eat. By 9 p.m. when they stood up to leave, they were both fairly drunk. On the stairs, Chris dared a hand in the small of her back. Not wanting to embarrass him, Tamsin let it stay there; though she had a dim premonition that this would mean more serious embarrassment for both of them later.

But later never came. As soon as they reached ground level, Tamsin’s phone began to buzz.

‘Shit, loads of missed calls. Sorry—’

Tamsin wedged the phone between ear and hunched right shoulder, leaving her hands free to fumble with the zip on her parka. Chris could hear the low chirrup of the dial tone.

‘Mummy? Mummy, is that you?’

Her face went tight as she listened. ‘Okay. I’m coming home.’

Tamsin pocketed her phone and started on the zip for a second time. ‘I have to go.’ Her voice was hard and strangely adult, different from any other tone he’d heard her use that evening.

‘Is everything all right?’ Something warned him not to touch her again.

‘I can’t explain. Sorry. I have to go.’ It was a pedestrian-only road but she checked for cars out of habit, three quick pecks of the head. Chris called after her but she was already gone, over the street and into the bright tiled mouth of the tube station.

He didn’t have her phone number. He didn’t even know her surname.

And so for Chris – who never had the chance to discover that Tamsin didn’t want to be kissed – the evening retained all the allure of unrealised possibility. Time magnified her charms in his memory. Tamsin informed his type; he looked for her height in other women, her slightness, those small, widely spaced breasts that had barely nudged the fabric of her T-shirt. To say he thought about her constantly would be an exaggeration, but she was, in a sense, always there – as an ideal, a measure against which everyone else was found wanting.

* * *

On the phone, her mother had been unintelligible. Tamsin assumed she had somehow uncovered the affair, but in fact, her father had simply announced that he was leaving and that he had been planning to leave for years. The trigger? Serena’s sixth-form scholarship to the Purcell School: Bertrand had wanted to wait until both his daughters had a secure future ahead of them before disrupting their home environment. Now that Serena’s musical career was more or less assured, he felt free to leave.

This was what he was explaining to his wife, for the fourth time that evening, as Tamsin came through the front door.

‘My god. My fucking god.’ Roz’s voice was muted with disbelief. ‘You actually think you’ve been considerate, don’t you, you shit—’

In the hall, Tamsin hung up her coat; she felt as if she were preparing for an interview. The house smelled like it always did: wood polish, old suppers, stargazer lilies, home.

When she stepped into the sitting room, both her parents turned to look at her. Her mother was dressed, incongruously, in a ritzy black cocktail number with a swishy little fringe of bugle beads around the hem. Her usual five-inch heels had been kicked off; standing in her bare feet on the thick carpet, Roz looked very small indeed. The corn on her middle right toe shone in the lamplight.

‘Your father’s leaving us. He can’t wait to get away, apparently. He’s been sick of us for years, apparently.’

Bertrand took a step towards his wife, one hand raised. ‘Roz, that’s not fair, that’s not what I said—’

‘But luckily for you, he’s deigned to stick around till now. So as not to disrupt your home environment. Now, isn’t that nice of him, Tamsin? Aren’t you going to say thank you to your father?’

‘Roz, this is between you and me. I won’t have you using Tam like this—’

‘He says there’s no one else, but I almost wish there was. I almost wish there was.’ Roz fought down a knot of hysteria. ‘I think I could understand that better than this, this dismissal—’

‘Valerie Fischer.’ Tamsin kept her voice as clear and steady as she could. Even in her anger, she was aware of the need to enjoy this longed-for consummation. ‘It’s Valerie Fischer, isn’t it, Dad?’

Father and daughter held one another’s gaze like lovers for three, four, five seconds before they remembered Roz.

She was motionless, a visionary staring through them to a strange new past.

* * *

From then on, everything was different. Roz was unable even to choose between red and green pesto without consulting her daughter. There was no longer any question of Tamsin leaving home; Roz needed her too much. She attended the Royal College of Music as planned, but stayed in her old childhood bedroom at home in Holland Park. After years of friction, mother and daughter were now inseparable. Tamsin acted as spokesperson, supplying all the fury and indignation and disgust that Roz herself couldn’t seem to muster.

‘Tamsin’s my sellotape,’ Roz would tell her friends. ‘She’s the only thing holding me together.’ She gave her mirthless laugh.

Tamsin’s friends were wary of her, unnerved by the thought of her long silence. She was newly inscrutable. She even looked different: gone were the Nirvana T-shirts and the belly-button rings. At first, her new role – as her mother’s counsellor, comforter, guard dog – felt like dressing up. Then she became it, and it grew harder and harder to remember a time when she and Roz hadn’t been bound to each other in this way. The scar above her belly button faded, from aubergine through lavender to a little raised sickle-shape the colour of clotted cream.

It was around this time that Roz retired from singing, after twenty-four years as a soprano soloist. When she and Bertrand first met, Roz had been a rising star in the opera world, already well known for her unexpectedly powerful vibrato. Her size was her USP: it seemed extraordinary that such a small person could make such a big noise with apparently so little effort. It also helped that she was beautiful. ‘Aha. Roz Andersen, the siren with the siren,’ Bertrand had quipped when they were introduced. Two weeks before their wedding, The Sunday Times ran a picture of Roz on the cover of the colour supplement, playing Desdemona in a big-budget ROH production of Verdi’s Otello. Then Bertrand’s career really took off, and together they became moderately famous. They were the golden-haired golden couple of music, rarely absent from Tatler.

Cigarettes had always been an occasional pleasure for Roz, a guilty secret kept carefully hidden from the agency that insured her voice. After the break-up, though, she took up smoking in earnest. A pack a day, then two packs. Everyone was worried. Roz lost count of the times she was warned about ruining her voice. Her response was unvarying: ‘I know. I don’t care.’ She took grim solace in this deliberate self-sabotage, which seemed to her to correspond with the magnitude of Bertrand’s crime.

(In fact, Roz’s voice was going anyway. Killing it off with a nicotine addiction induced by the trauma of separation was marginally preferable to watching her reputation fall into a slow, age-related decline.)

It was Tamsin, with her own unlimited supply of anger, who finally persuaded her mother to convert grief into rage. After three months of crying and smoking, Roz put on her sequinned Louboutins and climbed up onto the roof of Bertrand’s precious Merc, with a steely Tamsin and two fearful, admiring neighbours (both women) looking on. The next day, she distributed his wine cellar amongst her friends.

During the divorce process the Daily Mail got in touch, hoping for photographs. Together, Roz and Tamsin sifted through two decades’ worth of holiday snaps to find the perfect pose: Bertrand on the beach, off-duty, paunch relaxed, clutching a can of Boddingtons. The amphitheatre of his gut. In a second photograph he and his moobs reclined on a deckchair. A third showed him sad-arsed under a beach shower, muffin-tops slopping over the waistband of his designer trunks. The Mail ran all three. The headline was ‘Conductor in the Odium’.

When Roz moved out, Tamsin moved with her. Bertrand offered to pay the rent on a separate flat, closer to the Royal College; but this, like all his attempts at rapprochement, was met by the cool, almost professional hatred that had come to define Tamsin’s relations with him.

There were no boyfriends during the Royal College years. On her one, brief visit to Roz’s therapist, in the immediate aftermath of the divorce, Tamsin had been diagnosed with ‘trust issues’. ‘That’s unoriginal,’ Tamsin had told the shrink, feeling herself equally unoriginal even as she said it: the privileged rich kid from a broken home, wisecracking back to her jaded psych. Since then, several of her friends had suggested the same thing – that her father’s behaviour made it hard for her to have any faith in men. Tamsin had another explanation: the Royal College boys simply weren’t to her taste. They were too precious, too aware of their own talent. She slept with a couple of them, but more out of a sense of obligation to a hedonistic student lifestyle than any real desire. Mostly, though, she was at home with Roz, or working at her piano.

Occasionally she still thought about the boy on the train. The faint aversion was gone. She remembered only that he had been good looking, and that there had been wine, and candlelight, and an exhilarating sense of adventure. Most of all she remembered herself, with the disconcerting feeling she was remembering someone else.

Then she graduated from the College, fell in love with a history teacher several years her senior, and forgot about Chris completely.

* * *

When Tamsin was nineteen, her shoulders lost their angles; her arms and legs filled out; her nose and jaw took on a solidity that was unmistakably Bertrand’s. Her hair darkened to his exact shade of dirty gold, and even her newly swollen breasts appeared to belong more to her father’s side of the family than her mother’s.

Alarmed by the weight gain, Tamsin went to see her GP. She certainly wasn’t fat, but she was a lot bigger than she had been six months ago. Was it the Pill? Dr Lott didn’t think so. She scrolled briskly back up through her notes, rows of Listerine-green data on a convex black screen giving their laconic account of Tamsin’s life. Menstruation had started late, hadn’t it? This was probably just the tail-end of a mildly delayed puberty. ‘It happens sometimes. Nothing to be worried about. You’re a healthier weight for your height now, actually. It’s really not a problem.’

But it was. The mirror gave her back her father’s face, leonine, handsome, hated.