Читать книгу Calling on the Presidents: Tales Their Houses Tell - Clark Beim-Esche - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

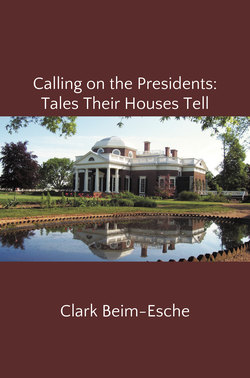

Thomas Jefferson: "...a work of art."

ОглавлениеThomas Jefferson's Monticello may well be the most beautiful house in the United States. It is more than a presidential home. It is, as one writer has observed, “the visible projection of its resident" (Hyland xvi). And, since the first time I traveled here to see this architectural marvel, I have felt that the spirit of Thomas Jefferson is remarkably present in this place—not in any spiritualistic sense, of course, but rather in the vivid display of his kaleidoscopic interests, his restless intellect, and his unending pursuit of knowledge. From the artifacts sent by Meriwether Lewis and William Clark in the front hall to the removable shelves of books in his study, from the dumbwaiters concealed in the dining room mantels to the polygraph machine that made ink copies of his letters, Jefferson has left an indelible impression here at Monticello of what it means to have been an inspired thinker in the Age of Enlightenment.

In the spring of 2012, Carol and I traveled to Virginia to revisit several of the great plantations owned by some of our early Presidents. Monticello was right at the top of our list of homes that I wanted to experience again before writing about Thomas Jefferson. But our first historical stop had the distinction of being a completely new site for us: Jefferson's Poplar Forest.

For many years I had known nothing of this house. Several of the books I had read about our third President had never mentioned the site, nor the fact that Jefferson himself had been its architect and had intended this locale to become a post-retirement haven for him, apart from the bustle and crowded conditions of Monticello. Only open to public view since 1998, this restored gem—the interior of which is still very much under construction—provides a wonderful glimpse into the mind of its creator.

As we turned off SR 661 into the entrance of Poplar Forest, a narrow unpaved road led us through dense woodlands for quite some time. Finally, as the road rose up a gradual hill, there on the left, Poplar Forest came into view. There could be no question as to the man who had conceived this home. It looked like a downsized Monticello: a brick structure with Doric columns holding up an architrave and frieze, crowned with a classic Greco-Roman pediment. It was pure Thomas Jefferson. And if a building's design can truly be said to reflect the consciousness of its architect, then the simplicity and modest scale of this home illustrated a key quality that must have lain at his very heart: a deep desire for balance and order.

Oh! Blessed rage for order, pale Ramon The maker's rage to order words of the sea, Words of the fragrant portals, dimly-starred And of ourselves and of our origins....

So wrote the great American poet, Wallace Stevens, in “The Idea of Order at Key West," and Poplar Forest immediately sent this verse coursing through my mind. This house is a hymn to symmetry, even more than Monticello, itself a most orderly structure.

Arranged around a central dining area that measures 20' by 20' by 20', the interior of Poplar Forest is comprised of a front entrance hall, flanked on each side by three octagonal bedrooms and, opposite the entryway on the other side of the dining room, a library sitting area, creating the building's external octagonal configuration. If ever a dwelling reflected a “Blessed rage for order," it is Poplar Forest, and, while its maker had no apparent interest in the “words of the sea," too far from this location to be heard, there is plentiful evidence of a desire for personal balance, equilibrium, and harmony. Nothing here is off center. The two chimneys on the right side of the home are counterbalanced by the two chimneys on the left side. The front porch is symmetrically echoed by the back porch, each with four columns set equidistant from each other, and each supporting a classic pediment. Both sides of the house feature identical projecting enclosed stairway pavilions with half arched windows to provide light for their interior passageways.

Nothing is out of place, no design element haphazard.

Throughout his life, Thomas Jefferson had experienced both great personal joy and agonizing tragedy. He had faced the rigors and stresses of foreign diplomacy as well as contentious political battles at home. Even his Presidency had yielded very mixed results. His first term had been a stunning success, the most notable achievement of which had been the Louisiana Purchase. His second term, however, had forced him to deal with both foreign and domestic treachery. Finally, in an effort to avoid a war, he had instituted an ill-advised and ineffective embargo that had made him extremely unpopular. By the end of his eight years as President, Thomas Jefferson was exhausted. In a now famous letter to a friend, he wrote, “Never did a prisoner released from his chains, feel such relief as I shall on shaking off the shackles of power." Poplar Forest, he believed, would be his refuge, his harbor from the storms of life where he could enjoy, in his own words, the “solitude of a hermit."

Sadly, enough, it was not to be. Perhaps because of his advancing years, or, even more understandably, perhaps because of his deep desire to feel himself surrounded by his remaining family and friends, Jefferson would not retire here, but rather to his beloved Monticello. Poplar Forest, his octagonal monument to symmetry, balance, and classical grace, would pass into other hands and would burn in 1845.

Today, the restoration and preservation of Poplar Forest have kept intact Jefferson's dream of an ideal retirement, a world of perfect order. But the man himself is not to be found here. He resides, still, ninety miles north, in Charlottesville.

On many occasions I have had to search diligently for a revealing symbol or sign of a President lying undiscovered or unheralded in some artifact on display in his home. At other times the residence itself may have suggested subtle truths that a casual visitor might overlook. Monticello poses no such challenges. Thomas Jefferson is present almost everywhere in this place. The home is a living testament to his interests, to his achievements, and to his character.

This is all the more remarkable because, unlike some other presidential homes, Monticello has had to have been completely reconfigured and reconstituted over the years. Jefferson's accumulated debt at the time of his death in 1826 was estimated to have been in the vicinity of $100,000. This was a colossal sum, easily more than a million in 21st century dollars. As the result, “A dispersal sale [was] held in 1827 [that] included his slaves, crops, household items, and furniture" (Clotworthy 45). The estate at Poplar Forest was sold. Lastly, in 1831, Monticello itself.

Happily for future generations, a Navy Commodore named Uriah P. Levy purchased the property in 1834, and he, and later his son, Jefferson Monroe Levy, worked tirelessly to restore Monticello. When in 1923 the Levy family finally sold it to the newly established Thomas Jefferson Foundation, this precious national architectural legacy had been saved from decay and destruction. Since that time the Thomas Jefferson Foundation has continued to maintain the home and has also worked to restore its interior and replace the long lost furnishings and objects d'art which records show had been present here with retrieved original pieces or authentic replicas. The result, as one book on presidential residences puts it, is that “Today Jefferson's Monticello is much as it was when he retired to enjoy his last years among his family and flowers" (Haas 29).

As Carol and I stood on the famous front porch of Monticello, together with a group of about twenty other guests, we listened closely to our articulate and entertaining docent, a man named Bill. He began our tour by informing us of the legacy that Jefferson had most wished to leave his nation: “Political liberty, religious freedom, and public education," Bill intoned. “These were the greatest, the most important values for Thomas Jefferson. These were the values that he chose to list on his tombstone, as he identified the accomplishments of which he was most proud—'Author of the Declaration of American Independence'—that's political liberty—'Of the Statute of Virginia for Religious Freedom'—that's religious freedom—'And Father of the University of Virginia'—that's education." Bill beamed at us, and I knew that we were in the hands of a docent who not only was knowledgeable, but who revered his subject as well. It would make for a most memorable visit.

We entered through the doors into the main hall, and Bill launched into descriptions that all docents of Monticello are obliged to give: identifications of various Lewis and Clark artifacts on display throughout the room; of peace medals given to a variety of Indian chieftains; of the famous weekly clock with the cannonball weights on its chains that pass through the floor. But then he drew our attention to some of the statuary in the room.

“Here in the main hall we see busts of Voltaire, Turgot, and Alexander Hamilton," he informed us. I would have expected Voltaire, a French philosophe with whom Jefferson had been ideologically in tune. But Hamilton? The man who had fought Jefferson's vision of America as an agrarian utopia? The man who had argued for the creation of a national bank and federal assumption of state debt following the Revolution? The man who had fought against Jefferson's election as President in 1800? I couldn't help asking Bill whether or not the presence of this marble bust was a subtle joke played on unsuspecting tourists.

“Actually," he answered me, “… we know that Mr. Jefferson did have a bust of Alexander Hamilton here in the main hall. Don't forget, despite their differences, it was Hamilton who had worked with Mr. Jefferson's friend, James Madison, to ensure the ratification of the Constitution by writing several of The Federalist Papers. And it was also Mr. Hamilton who tilted the final vote in the House of Representatives that broke the deadlock between Mr. Jefferson and Aaron Burr." All this was true, but nevertheless this bust represented to me an impressive indication of the extent to which Thomas Jefferson had been willing to forgive an old adversary.

Turgot was another matter. I had known that he, too, was a philosophe and a friend of Voltaire, so the pairing of these two sculptures was at least superficially logical. Also Turgot had admired the political impulse behind the American colonies' decision to separate themselves from Great Britain and create a new government based on republican principles. But Turgot had also vigorously opposed on economic grounds any French participation in aiding the colonies during the Revolutionary War. So why, then, place his image here when there were other Frenchmen, Lafayette comes immediately to mind, who had been more unreservedly supportive of the American cause? I believe Jefferson's decision may have been connected to the nature of Turgot's character.

History remembers Anne-Robert-Jacques Turgot as being dedicated to truth and fair play, and, like most French philosophes and Enlightenment thinkers, he was an ardent believer in the “natural rights" of all men. Furthermore Turgot's personality was frequently described as withdrawn, and he had difficulty expressing himself orally. As a writer, however, he was extremely compelling, and his words often led others to agree with his ideas. All this sounds strikingly similar to Jefferson himself. Perhaps the President had decided that it was only fitting that such a kindred soul as Turgot should be memorialized at Monticello.

After a brief first stop in the plantation office, we moved into the three chambers which comprised the President's private quarters: his library, study, and sitting room. It is here where the spirit of Thomas Jefferson is most conspicuously present. I also think it is important to observe at this point that each of these three rooms are both quite modest in size and are placed in a very close proximity to the public areas of the home, the main entrance, the formal parlor, and even the gardens right outside their windows. Bill assured us that, when Mr. Jefferson's doors were closed, no one was to disturb him, and, I'm sure, no one would have wanted to interrupt his reading, his researches, or his voluminous letter writing. But it should also be equally clear to anyone visiting this home that the President's rooms here at Monticello were very close to the constant activities of plantation life, particularly when one remembers that at the time of his sojourns here between political assignments, he was constantly surrounded by family and friends.

First, we entered the library. It was a marvelous scholar's nook with its reconstituted collection of over six thousand volumes. Of particular note to me was an octagonal table on which could be propped several books at one time (perhaps another example of Jefferson being ahead of his time: the original multi-tasker). Also, Jefferson's bookcases had hinges and handles which would allow them to be closed up and moved rapidly should the necessity arise. No more tragedies like the fire at Shadwell, his family home, that had destroyed his first library, I thought to myself. Here at Monticello, should an emergency occur, the books could be out the door in minutes. A scholar's invention, indeed, and another clear glimpse of the man who would also write, “I cannot live without books."

From the library our group passed into Jefferson's study. This sunny area was filled with scientific instruments and a swivel table (more multi-tasking here) on which, among other inventions, was the polygraph that had enabled Jefferson to make simultaneous copies of any of the nearly 19,000 letters he would write. Nearby, there was a telescope placed close to one of the windows, and next to it sat a portrait bust sculpture of Jefferson in old age. Was this Jefferson's reminder to himself that, as the 17th century poet Andrew Marvel had written, he had “heard Time's winged chariot hurrying near"? Bill would never have been so presumptuous as to have suggested an answer to such a question, but he did note that “Mr. Jefferson was fascinated with the natural world and had catalogued 330 varieties of nuts, vegetables, and fruits, planting many of them in his gardens here." A scholar's study and working laboratory indeed.

Jefferson's sleeping alcove, placed between this study and his sitting room with immediate access to each, featured a clock in the wall over the foot of the bed. “Mr. Jefferson was a self-proclaimed miser with his time," Bill reminded us. “There was always more to know, more to learn about the world, and his time was limited." As if to illustrate this point, Bill now reminded us that the President had died here on July 4, 1826. It had been fifty years to the day since his great Declaration had announced to the world the birth of a new nation, based on the revolutionary principle that a government's power, and even its legitimacy, rested squarely on the consent of its people.

We moved quietly into the sitting room and noted its simplicity as a place to dress for the day. Nothing else was particularly interesting about this room, and it led immediately into the hall before the formal parlor and dining room areas of the house.

The parlor was a gracious space which afforded beautiful views of the back gardens and walkways. Oil painted portraits of the Enlightenment luminaries, Bacon, Newton, and Locke, decorated the walls. The nearby dining areas also featured portrait busts, but here the theme was more strictly American, with images of Franklin, Washington, Lafayette, and John Paul Jones silently surrounding the tables.

The final room on our downstairs tour was directly opposite the plantation office. It was the so-called “Mr. Madison's room," named for its most frequent visitor, and I was fascinated to note that it was constructed in the shape of a perfect octagon. No wonder Jefferson had designed Poplar Forest as he had—the perfection and balance of that geometry had been a very conscious ideal for him.

The various gardens, the out buildings, including even the modest original almost Thoreauvian single room south pavilion where Jefferson and his wife Martha had begun their marriage, were all beautifully preserved and maintained, but for me it was the library and study that carried with them the most lucid insights into Jefferson the man. He had lived at a moment in history when the sum total of human knowledge could be contained in a single library, and Jefferson had made it his goal to learn as much of this accumulated wisdom as he could squeeze into a lifetime. He had also desired to add to this wealth of knowledge—to make his own discoveries and report them to the world. Monticello stands as a symbol of this goal and as irrefutable evidence of this desire.

Following our tour, Bill invited us to walk the grounds and visit the areas of the site for which no docents would be needed. There were informative displays in a number of these locations, many devoted to plantation life and the realities of slavery at Monticello. But it was my final stop at a lovely shop site which overlooked the plots of the vegetable and fruit gardens that would provide a lasting inspiration for me.

Like most tourists, I was interested in acquiring a two dollar bill (the only paper U.S. currency on which President Jefferson's image appears), and I knew that, if any place would have a supply of them, the shop at Monticello would. I was not disappointed, and, after a helpful worker had changed my two ones for a Jeffersonian two dollar note, I struck up a brief conversation with her.

“I love this home," I began. “It must be wonderful to work here." She was delighted with my enthusiasm and immediately assured me that, for her at least, it was a privilege and a joy. I continued, “Most Americans tend to think of it as some sort of plantation palace. But it's not that. Its rooms are small by comparison to European chateaux. It's not a palace, not even palatial!" She nodded as I spoke. “It's … it's …." My words were failing me. Very gently, she quietly finished my thought: “… a work of art."

“Exactly," I exclaimed. “That's it! A work of art." Monticello, designed and overseen by this man of the Enlightenment, was a gracious and elegant dwelling place. Like the house at Poplar Forest, it was also in its own unique way, a priceless work of art, well worth visiting, well worth preserving. And it is here, as John Adams said with his dying breath on July 4, 1826, that “Thomas Jefferson still survives."