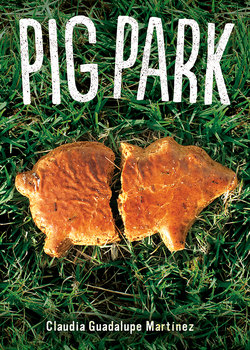

Читать книгу Pig Park - Claudia Guadalupe Martinez - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 7

The heat of the sun seeped between the slats of the blinds, warming my face. I rubbed the sleep out of my eyes. The sun was high enough to leak through my window, which meant I was late—very late.

I threw on my jeans and ran across the street.

Our group huddled in the center of the park. I pushed my way in. Casey Sanchez stood at the center. She wore a cut up styrofoam bowl tied around her neck with a belt. The homemade neck brace pushed the meat of her cheeks up like two bulging slabs of menudo. “What happened?” I asked. “Did you fall down the stairs at home or something?”

Casey grimaced and moaned.

Colonel Franco shook his head from side to side. “She got hurt yesterday. The boys will finish what we were doing with the bricks. You girls come with me to the Chamber of Commerce office,” he said.

Josefina was a red-faced beast ready to strike.

“I’m pulling you out of the field. It’s not safe,” Colonel Franco continued.

I couldn’t tell if he was serious. It didn’t seem like Casey had lifted a finger the day before. Besides, if it came down to a safety issue, everyone needed to go. Not just the girls.

“But—” I started and stopped. I shut my mouth. Banishment to the Chamber office was still a step up from being sent home.

I followed Josefina to the Pig Park Chamber of Commerce office, which was located in Colonel Franco’s basement. Stacey grabbed hold of the wheelbarrow, and Casey squeezed her body inside it. The wheelbarrow’s wheels squealed in protest. Stacey pushed hard and kept up the pace. She panted, but held her head up high like she was doing something very important.

“They’re like two great big toads on parade,” Josefina snarled under her breath.

I smothered a smile with my hand. Casey did look like a great big toad. At least they were wearing regular jeans and T-shirts this time.

Colonel Franco’s basement was dark and humid. A fluorescent bulb and two small windows didn’t brighten the room. The small oscillating fan blew air with all the power of a pinwheel.

It was just how a person might imagine. There were medals—commendations for service in several wars—all along one wall.

Colonel Franco ripped a dartboard from the opposite wall and took a case of beer out of the refrigerator—I assume to keep it out of reach. He carried everything away and returned with a large whiteboard. He hung it on the wall in place of the dartboard.

Casey and Stacey collapsed on the sagging couch in the corner. Josefina and I sat on the leftover stools around a card table.

“We need permits to build. You will help me fill out the paperwork. You’ll fill out applications to file,” Colonel Franco said. I swallowed and heard the saliva making its way down my throat. It was that quiet. I looked to Josefina. Her face was a perfect emoticon of anger. Her lips pursed tight until they curved downward into a downward parenthesis.

“We don’t even know how we’re building it yet,” I said.

“I suppose that would be a problem. I’m about done drawing up the plans. You can write letters to government officials so they know that we’re real people asking for real things, meanwhile. This is just as important as lugging bricks. I won’t ask you to like it, but that’s what you’ll do,” Colonel Franco said. He cracked his neck.

He moved to his desk. He pushed the big button on his computer. The fat screen hummed and vibrated, struggling to reanimate. Several minutes passed. He pulled out a box of pencils, paper, and a list of names and addresses and slid them across the table in front of us. “There is only one computer anyway.”

“Can we at least get a radio or a TV?” I asked. We needed something to cut the tension.

“Please.” Josefina finally opened her mouth.

“Please. Please,” Casey and Stacey joined in.

“We’ll see,” he grumbled. He disappeared. He reappeared after a minute with one of those antique televisions sets with rabbit ear antennas. I could see what Iker meant about his grandpa never throwing anything away. He put the TV down and disappeared again.

I flipped through a series of fuzzy channels and settled on the black and white movie station.

A movie called The Devil and Daniel Webster came on. I’d seen it before. A man cuts a deal with the devil in order to get rich. He becomes filthy rich at his town’s expense. Little by little, he loses control. The devil comes to collect. Daniel Webster, the hero, sues the devil for the man’s soul on the basis of his American citizenship.

“Would any of you ever sell your souls?” I asked.

“Sure, to be rich.” Stacey answered. “Besides I got a God-given American right to sell anything I want.”

“You don’t have any rights. Look at yourself. Not with a name like Sanchez,” Casey said.

“This isn’t Arizona—or Alabama,” Stacey shot back. I had opened a can of Sanchez. They bickered like two old ladies over coffee. I was sorry I’d asked.

“We better do some work if we ever want to get out of here,” I interrupted. I’m not sure why Casey and Stacey listened to me, but neither muttered another word. The pair leaned over their stacks of papers and scribbled.

“Wish it had been that easy an hour ago,” Josefina said.

I shrugged. My toes danced against the linoleum below. I stared at the paper in front of me. My fingers were warm and moist around the pencil. I looked over at Josefina’s letter. She’d written a standard Please help us / Thank you letter. I wondered how many Please help us / Thank you letters anyone should ever have to read. I tapped the tip of the eraser against my forehead until the words rattled out, and I began writing.

My name is Masi Burciaga. I am fifteen years old, and I have lived in Pig Park my whole life. My family owns a bakery here. We are among the few who didn’t move away when the American Lard Company closed down. That may change soon if we don’t find a way to bring people back.

So a bunch of us want to hang out, build a pyramid in the middle of Pig Park and save our neighborhood. Are you in?

I was rambling, but I didn’t care. I copied the text onto a clean sheet. I copied it again and again, changing the ‘dear whomever’ part each time. My knuckles turned white and a soft bump began to form on my middle finger.

When Colonel Franco came in and announced that we could go home, I jumped up and placed my stack of letters on his desk. I rushed upstairs and breathed in the thick hot air.

Josefina stood outside. She patted her face and winced. “I told you. It’s time to throw in the towel. This feels more like summer school than summer camp. These letters aren’t going to do anything. Who even reads letters written in pencil anymore? This isn’t nineteen ninety-two.”

“At least your skin will have time to heal,” I said. Once again, I didn’t know what else to say to her. I could see her point. She was right about the letters. I was sure they would end up under a pile of coffee-stained papers that everyone would forget.

I hadn’t escaped the bakery for this. If that boy from the park was real and came back, I would miss it. It was a silly thing to suddenly think about, so I didn’t say anything to Josefina. As much as I couldn’t bear to sit in Colonel Franco’s basement one more day, I also didn’t want Josefina to have another reason to throw in the towel. At least we were still together.

We walked to the south end of the park where we found the boys clearing the overgrown grass from an area marked off by blue duct tape, about eighty by eighty feet, a perfect square. It looked to be about one eighth of the park. They were also digging a trench along the tape.

Marcos looked up and jogged over to us. I caught myself eyeballing his biceps—the way they strained against the cotton of his shirt as he ran. What was it with me? Maybe the summer heat was making me boy crazy. I told myself not to stare.

“Did you miss me today, Masi?” His hand shot up and tucked his hair behind his ear.

“About as much as I missed scrubbing dishes,” I said, a little too quick.

“I think that’s a yes.”

Red inched up my cheeks. I changed the subject. “What are you doing tomorrow?”

“We’re digging out the rest of the trench along each side of the pyramid,” he said. Marcos grinned and ran back to where the other boys were still working.

“Your brother is weird.”

“Ugh. I can’t believe we’re related sometimes.” Josefina crossed her arms over her chest and paced back and forth. “Masi, I don’t want to shovel dirt any more than I want to write letters, but it would serve Casey and Stacey right if we figured out a way to get Colonel Franco to let us work outside again. They’re not going to be the reason everything changes for me. I get to decide.”

A smile crept onto my face. I didn’t care about Casey and Stacey. It only mattered that it made Josefina want to stick around for the time being. Everything would go back to normal once we saved Pig Park.