Читать книгу Michiko or Mrs.Belmont's Brownstone on Brooklyn Heights - Clay Lancaster - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеMICHIKO’s eyes were usually long and narrow, but at the moment they were round with wonderment. They were as round as the big plane’s porthole through which she was gazing down at the tall towers reaching skyward in the crowded city far below. Michiko was on her knees in the seat in order to get the best possible view of the strange place she was to make her new home. She half expected the plane to light on top of one of the tall buildings, like an eagle on its nest in the mountains near the village where she had lived in Japan, but the plane passed over the heart of the city.

Michiko felt her stomach sink when the motors were turned off and the plane nosed downward for the landing. There was a flat gray area on the ground ahead, and she held her breath as the plane approached the earth. She closed her eyes, too, and only popped them open when the wheels touched the landing strip. The plane taxied in a wide arc and came to a stop near the terminal.

“Come, Michiko,” called the stewardess, for the little girl’s face was still glued to the windowpane. Michiko turned around and took the hand held out to her. Together they made their way off the plane, the tall stewardess in a dark blue uniform and the tiny Japanese girl in a bright pink kimono.

Mrs. Sakurai, the wife of the minister of the Japanese Church, had come to the airport to meet the newcomer. She stepped forward to greet the little girl, but the child was expecting someone dressed like herself. Instead, Mrs. Sakurai was wearing a tailored tweed suit, and Michiko did not at first recognize her as being Japanese.

“Michiko!” Mrs. Sakurai called.

Suddenly realizing who she was, Michiko bowed deeply in the Japanese manner, her hands placed on her thighs. Mrs. Sakurai bowed in return, but it was brief and awkward.

“Did you have a nice trip, dear?” Mrs. Sakurai asked.

“Oh, yes, everything was very good,” replied the little girl.

Michiko bid good-bye to the stewardess and took Mrs. Sakurai’s hand. Her red lacquered geta, or wooden clogs, went clack, clack, on the pavement. As they walked toward the terminal, Michiko told Mrs. Sakurai about the city she had just seen from the air.

“I am glad you studied English in Japan,” Mrs. Sakurai remarked. “You will get along so much better in this country since you can speak our language.” Michiko looked up into Mrs. Sakurai’s face, puzzled over her use of the words “our language.” Yes, although Mrs. Sakurai’s face was Japanese, everything else about her was thoroughly American, Michiko decided.

They entered the building and went to the desk where passengers claimed their luggage. Michiko spied her own. It was different from the others, being a square box of wood tied in a blue cotton handkerchief with black and white Japanese characters on it. The porter handed it over to its owner without having to look at the identification tag.

Mrs. Sakurai led the way through several long corridors to the front of the building. They got into a taxi cab. Mrs. Sakurai spoke to the driver. The taxi started off down the curved ramp and Michiko fell over sideways. She had hardly righted herself when the car swung into the main drive and she keeled over in the opposite direction. Looking over at Mrs. Sakurai, who seemed to be keeping her balance, and following her example, Michiko braced herself with her arms on the seat when the cab turned into the highway leading to the city. This way she remained reasonably upright.

The highway passed through a continuous village. The buildings became larger and larger and drew closer and closer together.

“Do people live in all these houses?” asked Michiko.

“Yes. Most of these buildings are apartment houses,” Mrs. Sakurai answered.

“How many people?” inquired the little girl.

“About eight million,” was the reply.

Michiko tried to imagine a figure “8” followed by an endless chain of zeros and studied the row upon row of houses with greater interest.

The highway left the residential section and for awhile ran along the bank of a broad river. Mrs. Sakurai said it was called the East River. Then the cab crossed over a street spanning the river and plunged into the congestion of the city. The sun appeared to have gone down, but it was only because of the exceedingly tall buildings, which rose like great cliffs on either side of a narrow canyon. Cars moved in unison, and all came to a halt at the same time.

“Why do they all stop at once?” questioned the little girl.

“The drivers stop when they see the red lights,” Mrs. Sakurai explained.

“I don’t blame them. The red lights are pretty,” remarked Michiko. Then she added, “But why do they run so fast from the green cats’ eyes—are they afraid of them?”

“Of course not,” laughed Mrs. Sakurai. “It’s because green means ‘go’ in America.”

Michiko slid back in her corner of the seat and looked at the shop windows.

The taxi sped past a large group of government buildings. Some were large and ominous, with massive porticoes overhanging the street. Others were low and spreading, set in pleasant little parks. The taxi entered the approach to a bridge. The bridge had immense stone towers at each end, and swung between them were great webs that must have been spun by an enormous spider. Away to the right, in the middle of the harbor, stood a giant green lady holding what looked like the stub of a parasol over her head. Mrs. Sakurai said that the figure was a copper statue representing the Goddess of Liberty. Michiko was reminded of another big statue she had seen, the Buddha at the Temple of Kamakura, who sat serenely on a broad platform, his hands folded in his lap. Michiko had been taken to visit him once, in a school bus back in Japan. She thought of the classmates she had known and wondered if they ever thought of her, now that she was so far away.

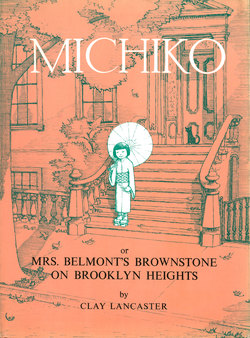

The cab crossed the bridge and passed along a wide avenue. It circled a white building with a round dome and then darted into a narrow side street lined with stores. Mrs. Sakurai told Michiko that this part of the city was called the Heights. A few blocks farther, the cab turned into another street that was tree-shaded and had fine houses set close to the sidewalk, with rows of steep steps leading up to doorways with carved enframements. The taxi pulled over to the curb in front of one and stopped.