Читать книгу Sitting With The Sages - Clifford E. Mclain - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеClaude Clifford McLain

No single preacher/pastor influenced me as much as my father, Claude Clifford McLain. C. C., as he is fondly called posthumously today, was born December 28, 1912, into wealth and privilege to John and Almeta McLain. His father was an entrepreneur and the son of a white farmer, who gave him eighty acres of land. Within a short time, John McLain owned a six-hundred-acre farm, two sawmills, three taxicabs, and the only commissary (grocery store) in his hometown, Choudrant, Louisiana. He also owned racehorses and was the largest stockholder in the local bank.

John was the apple of Claude’s eye, his idol and hero. At age six, in September, 1919, everything changed. Three months before C. C.’s seventh birthday, his father John was shot in the back by a white employee. John McLain died the next day on his forty-second birthday. A transcript of the court record laid on the dining room table of our home for years. All of the money, stock, mills, and most of the land were taken from Claude’s mother by the manufacture of “You owe me.”

Growing up, Claude walked to Grambling to get a high school education. He endured humiliation and demeaning acts by whites, who rode the buses, and often, they threw their excrement from the bus window on him as he made the ten- to twelve-mile walk one way in pursuit of his high school diploma. After Grambling Negro Normal School, C. C. worked and studied under George Washington Carver at Tuskegee Institute during the Great Depression. While reading books about Dr. Carver’s life, particularly the one entitled In His Own Words, the writer of the foreword suggested that Dr. Carver’s voice was pitched higher than the average woman because he was probably castrated to be sure there would be no children fathered by Carver being that he lived in the “big house” with whites.

My father told us that, upon meeting Dr. Carver, he first heard his greeting from behind some rosebushes. “May I help you?” Carver asked in a very high voice. C. C. had just arrived by freight train and walked to the campus. He worked a while for Dr. Carver and Dr. Moreland, learning farming and how to administer medication to livestock. This was extremely helpful during his years of cattle farming, planting, growing and harvesting southern plantation pine trees. After Tuskegee, C. C. attended and graduated from Bishop College located in Marshall, Texas, at the time.

Our mother, Mildred Oliver McLain, told us that Dad’s first marriage ended when his wife Grace died in Tuskegee while he was a student. There were no children born to that union. After studying at Bishop, Claude was a teacher and the principal at the Saint Rest Elementary School. C. C. would laugh upon reflecting on his many responsibilities as principal/teacher at St. Rest. This was a time of growth and learning for both him and his students.

During the late 1930s and early forties (1940), C. C. would come home from teaching school and work at the sawmill, which was less than a half mile from the lot he and mother had purchased. He received no monetary pay. Instead, he was paid in lumber. By 1942, he had completed the nine-room framed house that still stands at 1419 Oakdale Street in Ruston, Louisiana. He hammered and nailed even after dark while mother held a flashlight.

In the mid-1940s, C. C. pastored two churches, New Hope in Ruston, Louisiana, and Galilee in Hodge, Louisiana. While pastoring the New Hope Baptist Church in Ruston, in the early 1950s, C. C. was told by a member of the church, “Pastor, you know what happens before our night service is over?”

“No, what happens?”

“A lot of the members go across the street to the Red Onion.”

“What is the Red Onion?”

“You know, it’s a joint, where they dance and stuff. It’s a shame.”

C. C. said, “I’ll go over there if you all go with me and show me how to get in.”

“Yeah, we’ll go. Everybody’s talking about it. It’s a lowdown shame.”

The next Sunday night worship, after the offering, C. C. asked the members who did not leave after the offering to remain for a few minutes.

After the offering, the members who frequented the “Red Onion” left as before. C. C. spoke to the members that remained.

“I’m going over to the place across the street where some of you say our members are. All of you who will, follow me. We are going just to see, not talk.”

The “Red Onion” was just across the street from the church. C. C. walked out, followed by deacons and other church leaders and members. As the pastor and church members walked in single file toward the Red Onion, they began to hear the music. They heard blues and swing growing louder. When they entered, the dancing church members were “getting down.” They had no idea that their space had been invaded by their fellow church members. Suddenly, someone yelled, “O Lord. It’s the pastor and deacons. They are in here.”

The dancing churchgoers still had their choir robes on or across their shoulders. Dancing ushers wore their church usher badges. All were adults who knew the latest dance craze. Immediately, panic struck. The dancing churchgoers ran in every direction. But the only way out was the front door. They were trapped. When the dancing and music stopped, C. C. said, “Shame on you. All of you church members should be ashamed. And before you sing in the choir or usher again, you will have to talk to the church congregation.”

Later, when I grew older and talked to C. C. and reminisced with some of those who had been involved in the dancing, I was told, “Boy, I wished Jesus Himself had come into that place, rather than your father. I was so embarrassed.”

The next Sunday worship was very sobering. More than twenty-five persons came before the church at the time of the invitation to discipleship. All of them apologized and were restored. This was a time before television and very few people had radios. But this action spread throughout the city by word of mouth and established C. C. as a stern pastor.

In September 1956, when coming home from Lincoln High School, I noticed my dad’s big dog wrestling with another dog. Being a lover of animals, I walked between them and was bitten on the knee. My mother saw it from the kitchen window. She was frantic. My dad came from his study into the kitchen. He was quite agitated. I had no idea how serious it was.

There was an immediate search for the strange dog. Our dog had been vaccinated. The police looked throughout the city without any success in finding the dog. I began taking the regimen of fourteen shots at Green’s Clinic to prevent rabies.

After the painful round of fourteen injections for fourteen consecutive days, I became very ill. I had no appetite and began losing weight. When my condition did not improve, I was admitted to Ruston General Hospital. I spent the next eight months in and out of the hospital. I missed the remainder of that school year. One evening, I heard C. C. and my doctor in a serious discussion.

“Reverend, do you want to tell your son or would you like me to do it?” Dr. Bruce Everett asked.

“No one is going to tell my boy he isn’t going to live,” Dad replied.

Doctor Everett left the room. My mother was in tears. My father spent the nights with me, and my mother stayed home with my siblings and prepared to go to work at Lincoln Elementary School each day. On the night of the serious discussion with the doctor about whether I would live or not, C. C. came to my bed, and before going to sleep, he knelt and prayed a brief prayer.

“Lord, I’ve been standing by your Son for these years. I just need you to stand by mine.”

This was around the beginning of spring. I was released from the hospital a few days later.

All the ministers included in this writing were introduced to me by my father. There are many others, but these are the ministers that greatly influenced me and my generation. I was influenced by John Bishop Huey, Clyde Lewis Oliver, David V. Martin, J. D. Jackson, David Matthews, and L. D. Scott, who said, “Son, you are standing on your father’s shoulders, so you are expected to go higher.”

In 1957, while my parents were attending graduate schools in New York, my mother at Columbia University and C. C. at Union Theological Seminary, I met Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. C. C. took my sister Patricia, brother John, and me to Brooklyn, New York, to worship at the Cornerstone Baptist Church; Dr. Sandy F. Ray was the pastor. We sat in the overflow section after walking several blocks looking for parking. I watched Dr. King mount the pulpit dressed in a dark gray jacket, matching gray slacks and tie with “spit” shined wing tip shoes. Even the youngest worshippers like me were on the edge of our seats as Dr. King told of the Montgomery bus boycott and combined his word power with the story of Calvary.

After a standing ovation, C. C. said, “We’ll wait until the last person shakes his hand, and we’ll go speak to him and leave.” After Dr. King had given and received the last hug and handshake from the well-dressed worshippers, he looked in our direction.

“MC,” he said, very surprised to see C. C. “What are you doing here in New York?”

“My wife and I are attending grad school here. I want you to meet my children, and I want them to know you.” Beginning with my sister Patricia, then John, Dr. King shook our hands, asking our names and what grade we were in. When it came my turn, he asked “And what do you want to be when you grow up? A preacher like your daddy?”

I replied very softly, “Yes.”

I remember trying to preach at age seven, only to not receive encouragement from C. C., he didn’t encourage “boy preachers.”

The next year, 1958, less than nine months later, my sister Claudette was traveling alone by train from Ruston, Louisiana, our hometown, to Atlanta, Georgia. She had been accepted as a freshman at Spelman College. Our house phone rang, and C. C. left the dinner table and answered. We knew something was wrong when we heard C. C. telling her, “Calm down. Don’t cry. Listen carefully, find a uniformed worker of the train, tell him what happened, and they’ll put you on a train back to Atlanta.” She had missed her stop. Next, C. C. reached in a nearby drawer and retrieved an address book; he gave information to the operator. Moments later, as all of us gathered around C. C., he said, “Mrs. King, this is C. C. McLain in Ruston, Louisiana. I know your husband and saw him last year in New York.” After exchanging pleasantries, C. C. explained the dilemma and then hung up the telephone.

“What is it, Claude?” my mother asked.

C. C. explained, and we returned to the dinner table. About three hours later, there was a call from Atlanta. Mrs. King and two other ladies from Ebenezer Baptist Church had gotten Claudette situated in a dormitory at Spelman.

Later, C. C. explained how he first met MLK Jr. “The National Baptist Congress met in Denver, Colorado, in 1956. This was around the midway point of the Montgomery bus boycott. By this time, King had become a national figure. So the congress elected him as vice president. However, J. H. Jackson, the convention president, did not agree to King being vice president of the congress, and he arrived in Denver, Colorado, and removed King from the position. Martin was hurt. He was young, in his twenties. Because of Dr. Jackson’s decision, most ministers seemed to back away from Martin. I spent a half day consoling him,” C. C. said.

“I said to Martin, the congress nor the convention will provide a platform large enough for you and your work. The Baptist denomination will not be big enough. God will provide a universal platform for you. Just wait and see,” C. C. said. “Martin was sad, hurt, and embarrassed. Jackson demonstrated envy and perhaps anger toward King in his publications. This may have been because at the beginning of the Montgomery bus boycott, Jackson offered to provide buses for the boycott, but King refused.”

“This would only hurt our cause. And the people we want to change will accuse us of being led by outside agitators,” King replied.

C. C.’s advice and encouragement to King proved to be correct.

C. C. and other preachers on my street were members of a group called the Nicodemus Club. They met at night to strategize on registering to vote and correct other social injustices. In 1945, C. C. was one of five African Americans to register and vote in Lincoln Parish. When Edwin Edwards became governor of Louisiana, he appointed my father chairman of the Lincoln Parish supervisor of elections. C. C. pastored at least six different churches before becoming pastor of the Little Union Baptist Church of Shreveport, Louisiana.

While pastoring the New Hope Baptist Church in Ruston, from 1948 to 1959, C. C. was elected the moderator of Liberty Hill Baptist Association in Grambling, Lincoln Parish, where he served twenty-two years. He was elected vice president at large of the Louisiana Baptist State Convention under Dr. T. J. Jemison and served until his death in 1991. After being encouraged to preach by C. A. W. Clark, C. C. was called by the church to fill the vacant pulpit at Little Union Baptist Church in December 1958. He became pastor in 1959. During the first year, C. C. had become actively involved in the civil rights movement. He met the buses of the freedom riders, helping them post bail. Little Union BC became the epicenter of the civil rights movement. C. C. had supported Dr. King during the Montgomery Movement by sending monthly financial contributions.

Little Union, a church that began on the Brownlee Plantation (Bossier Parish) in 1892, after convincing a reluctant plantation owner who would not allow a large number of Blacks to meet. Organizers told him, “We are just a Little Union, boss.” With that, the church was organized.

In early fall, 1959, in the hallway of the parsonage of the Looney Street location was the telephone. The phone rang, I picked it up and said hello. The voice on the telephone was a white man who spoke a very racist, vulgar threat. I had never heard so much profane verbiage. I dropped the receiver. C. C. was standing behind me and immediately picked up the receiver and said hello. He interrupted the caller, saying, “Do you know where I live? I’m going to give you the directions. Is your insurance paid up? Mine is.” The caller hung up. Looking into my dad’s eyes, I saw a man who was dangerously determined to gain freedom at any cost! My father was the opposite of Dr. Martin King; he would be nonviolent if left alone. Death threats were phoned into the parsonage every day. My father was threatened but not bothered by the naysayers.

In 1962, Dr. King spoke at Little Union BC when no other pulpit was open to him. As the death threats phoned to the parsonage increased, during his visit, he refused to stay at the parsonage. He knew he was going to die and wanted to be alone.

After Dr. King’s speech, he and CC talked about a march the next day.

“I’ll see you tomorrow downtown on Texas Street,” King said.

“What will you be doing tomorrow on Texas Street?” CC asked King.

“We’ll be marching to call attention to our struggle.”

“I don’t march, Martin.”

“Why not?” King asked.

“Man, I’ll destroy your movement. If one of those white people put their hands on me, I’m sure there will be at least six funerals,” C. C. responded.

“Okay, I understand. You stay here and pray for us.”

C. C. was a man who knew his limitations, his strengths, and his weaknesses. He seemed never to outlive the events of 1919. He forgave, but he never forgot.

Men came to the house late one night in an attempt to get under the house. They couldn’t! Mother had told all of us, Pat, John, and me, “Get on the floor and stay there until I tell you to get up.” When C. C. opened the side door to the driveway, my mother said, “Claude, don’t go out there!”

C. C. responded, “I aim to kill or be killed tonight!”

The anxious footsteps of the men could be heard in their hasty retreat.

In 1963, I saw more trouble, but this time, it was at a church. On September 15, four young girls were killed at the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, when it was bombed. The following Sunday, September 22, Dr. King had asked for a national day of mourning. In Shreveport, Louisiana, a group of students and residents from the black community attempted to march from Booker T. Washington High School to the Little Union Baptist Church. The march was stopped by local police. The marchers were determined to get to the church, and they chose alternate routes. The church was full, but at the end of the worship service, police rode horses inside enough to beat two ministers, with Reverend Harry Blake being beaten severely. He had been dragged outside to the front of the church.

After being licensed and ordained by C. C., I entered the pastorate. In my second year of pastorate at Zion Travelers Baptist Church in Ruston, Louisiana, I decided to attend seminary at Princeton Theological Seminary in New Jersey. C. C. advised me that it was a noble idea; I would only be able to use about 10 percent of what I learned while dealing with my congregation, especially as an administrator in the black church. C. C. was a strong advocate for preparation. He had taught mathematics at Jackson High School for sixteen years before resigning and giving full time to the ministry.

When I was starting out as a young preacher, he observed my dress as I was leaving to preach. “Your clothes should not be louder than your sermon,” he said. “The preacher has to wear well, rest well, and ride well.” C. C. believed that formal training would help shape the preacher’s theology and expose him to the great homiletic minds of my era.

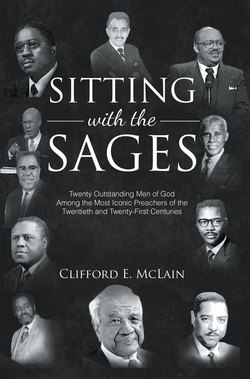

| Dad (C. C. McLain) Baby picture | Granddad (John McLain) |